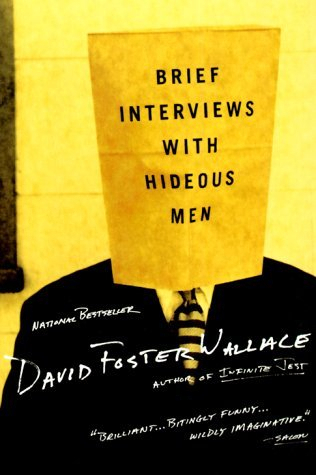

Properly describing David Foster Wallace’s Brief Interviews with Hideous Men involves using all of those words that I hate to see in any book review: “radiates,” “pathos,” “poignancy,” “gut-busting laughs,” “existential crises of identity in the post-modern world,” and so on. Now that I have them out of the way, let me tell you why you should read this book: it will make you laugh, it will make you cry. Out loud. After you read it, you will want to press it on other people, who will say, “Yeah, sure, okay”; only their eyes’ will be slightly-slanted, their mouths just a bit crooked, even their nose will appear askew at your demand. They will hurriedly change the subject–you’ve already foisted so many unwanted books on them, and who even has time to read now?–but you will persevere! “Here,” you’ll say, “Read “A Radically Condensed History of Postindustrial Life”–it’s only two paragraphs! You can read the whole thing in under a minute!”:

When they were introduced, he made a witticism, hoping to be liked. She laughed extremely hard, hoping to be liked. Then each drove home alone, staring straight ahead, with the very same twist to their faces.

The man who’d introduced them didn’t much like either of them, though he acted as if did, anxious as he was to preserve good relations at all times. One never knew, after all, now did one now did one now did one.

And, as they finish reading, you’ll beam at them and nod your head knowingly. They’ll look a little confused, perhaps bored. “It’s like an overture, see? It’s like, about loss, the inability to connect, the masks we wear to hide our hideousnessnesses.” Your victim will nod politely and begin to bring up an interesting thing he saw on the local news concerning pet ownership, but you’ll cut him off before he can get out of this. “Check out the “Brief Interviews with Hideous Men” sections that permeate the book–they’re like little vignettes, interviews where you only get the interviewee’s responses. They’re funny, shocking sad–they’re really good! Also, check out my favorites– “Adult World (I)” and “Adult World (II)”–these stories are about a wife who it turns out doesn’t really know her husband at all. Just read the beginning– ”

For the first three years, the young wife worried that their lovemaking together was somehow hard on his thingie. The rawness and tenderness and spanked pink of the head of his thingie. The slight wince when he’d enter her down there. The vague hot-penny taste of rawness when she took his thingie in her mouth–she seldom took him in her mouth, however; there was something about it that she felt he did not quite like.

“See?” you’ll demand uncaringly of your now-obviously exasperated detainee, “See? Sex! It’s got sex in it! Everyone loves to read about sex, especially weird awkward sex!” Your victim will now stand up, feigning the need to visit the restroom. But you won’t let him go that easily! “There’s another series of running vignettes that unify the book’s structure, making its sum more than just a collection of previously-published stories–check out a selection from one of the “Yet Another Example of the Porousness of Certain Borders” series”–

“Don’t love you no more.”

“Right back at you.”

“Divorce your ass.”

“Suits me.”

“Except now what about the doublewide.”

“I get the truck is all I know.”

“You’re saying I get the doublewide you get the truck.”

“All I’m saying is that truck out there’s mine.”

“Then what about the boy.”

“For the truck you mean?”

Your poor visitor is now literally walking away from you, ignoring the book in your hands, yet still somehow politely smiling–though only with his mouth–his hard eyes show how much he hates you right now. As he retreats to the toilet, your feelings hurt, you comfort yourself by declaring that he doesn’t read anyway; besides, he wouldn’t be able to figure out that “Tri-Stan: I Sold Sissee Nar to Ecko” was a retelling of both the Tristan and Isolde and Narcissus and Echo stories, set in Hollywood; he wouldn’t appreciate the book’s themes of child-abuse, repressed (false?) memories, and lost love. Philistine.

When he comes out of the bathroom you chit-chat a little more and then he’s ready to go. He holds his hand out toward the book. He wants to borrow the book. He wants to take your book. Oh shit. What have you done?

_____________________________________________________________________

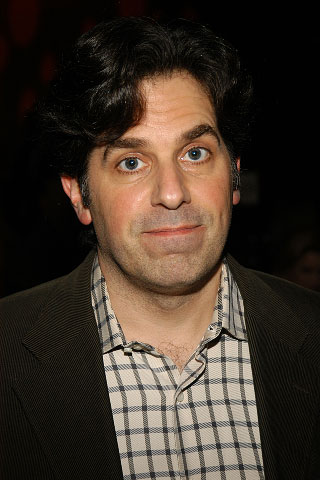

Believe it or not, that dude who plays “Jim” from The Office is directing a movie version of Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, scheduled to come out later this year.

You can read the first part of this series here.