I have terrible writer’s block. It’s not that I have nothing to say, it’s just that I can’t seem to say it. Or that I write sentences like the previous one and shudder at their awkward clunky artless awfulness. But I’m gonna press through it, write through it, and share a few thoughts on what I’ve read this week–

First up: Adam Langer’s new novel, The Thieves of Manhattan, a send-up of the publishing industry that sets its targets directly on the current swath of (faked) memoirs that have done gangbusters for publishers in the past few years. Ian Minot is a broke-assed barista one fuck-up away from an overdue firing, who moves from the Midwest to make it as a writer in the big city. Only he’s not doing so well–in contrast to his gorgeous Romanian girlfriend Anya whose literary star is on the rise. For Minot though, this isn’t the worst–that would be the rampant success of über-poseur Blade Markham, a wanna-be gangsta whose memoir Blade on Blade is a blatant fabrication (albeit a fabrication that no one but savvy schlemiel Minot seems to notice (or, at the least, be bothered by)). I read the first fifty-odd pages of the Thieves in one sitting–a good sign to be sure. Langer’s Minot’s voice is familiar territory, the boy who loves to mock the literati he would love to be a part of. In one of the signal moves of his patois, the names of famous authors (and characters) regularly replace common nouns–a bed becomes a proust, a full head of hair is a chabon, sex is chinaski and so on. Minot seems to be headed to running his own grift soon with the help of a man he appropriately calls the Confident Man–should be good stuff. Full review forthcoming. The Thieves of Manhattan is available July 13, 2010 from Spiegel & Grau.

First up: Adam Langer’s new novel, The Thieves of Manhattan, a send-up of the publishing industry that sets its targets directly on the current swath of (faked) memoirs that have done gangbusters for publishers in the past few years. Ian Minot is a broke-assed barista one fuck-up away from an overdue firing, who moves from the Midwest to make it as a writer in the big city. Only he’s not doing so well–in contrast to his gorgeous Romanian girlfriend Anya whose literary star is on the rise. For Minot though, this isn’t the worst–that would be the rampant success of über-poseur Blade Markham, a wanna-be gangsta whose memoir Blade on Blade is a blatant fabrication (albeit a fabrication that no one but savvy schlemiel Minot seems to notice (or, at the least, be bothered by)). I read the first fifty-odd pages of the Thieves in one sitting–a good sign to be sure. Langer’s Minot’s voice is familiar territory, the boy who loves to mock the literati he would love to be a part of. In one of the signal moves of his patois, the names of famous authors (and characters) regularly replace common nouns–a bed becomes a proust, a full head of hair is a chabon, sex is chinaski and so on. Minot seems to be headed to running his own grift soon with the help of a man he appropriately calls the Confident Man–should be good stuff. Full review forthcoming. The Thieves of Manhattan is available July 13, 2010 from Spiegel & Grau.

I’ve also been reading William H. Gass’s first novel, Omensetter’s Luck. It’s weird, wonderful, Faulknerish in its loose (but somehow layered and constructed) stream of consciousness. Omensetter’s Luck comprises three sections, each progressively longer; I finished the second one today, and so far the novel seems to dance around a description or accounting of its namesake, Brackett Omensetter who carts his family into the small sleepy town of Gilean, Ohio, and immediately perplexes the townsfolk with his amazing luck. As Frederic Morton put it in his contemporary 1966 New York Times review, “It quickly becomes apparent that as other people have green thumbs, [Omensetter] has a green soul. The cosmos and he live in mysterious congruity.” There’s much to commend and unpack in Gass’s writing here, but the pleasure of his musical rhythm are enough for me now (in my writer’s block, I retreat to aesthetic criticism [shudders]). Besides, do I really have to recommend this novel when David Foster Wallace already did so in his semi-famous list “Five Direly Underappreciated U.S. Novels > 1960”? No, I don’t, that’s right. Here’s Wallace on Omensetter’s Luck: “Gass’ first novel, and his least avant-gardeish, and his best. Basically a religious book. Very sad. Contains the immortal line ‘The body of Our Saviour shat but Our Saviour shat not.’ Bleak but gorgeous, like light through ice.”

I’ve also been reading William H. Gass’s first novel, Omensetter’s Luck. It’s weird, wonderful, Faulknerish in its loose (but somehow layered and constructed) stream of consciousness. Omensetter’s Luck comprises three sections, each progressively longer; I finished the second one today, and so far the novel seems to dance around a description or accounting of its namesake, Brackett Omensetter who carts his family into the small sleepy town of Gilean, Ohio, and immediately perplexes the townsfolk with his amazing luck. As Frederic Morton put it in his contemporary 1966 New York Times review, “It quickly becomes apparent that as other people have green thumbs, [Omensetter] has a green soul. The cosmos and he live in mysterious congruity.” There’s much to commend and unpack in Gass’s writing here, but the pleasure of his musical rhythm are enough for me now (in my writer’s block, I retreat to aesthetic criticism [shudders]). Besides, do I really have to recommend this novel when David Foster Wallace already did so in his semi-famous list “Five Direly Underappreciated U.S. Novels > 1960”? No, I don’t, that’s right. Here’s Wallace on Omensetter’s Luck: “Gass’ first novel, and his least avant-gardeish, and his best. Basically a religious book. Very sad. Contains the immortal line ‘The body of Our Saviour shat but Our Saviour shat not.’ Bleak but gorgeous, like light through ice.”

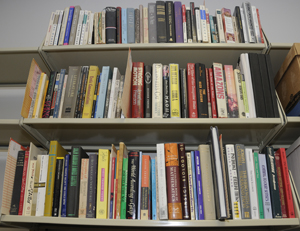

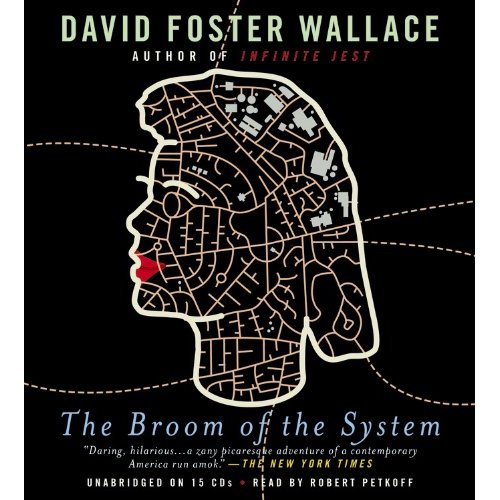

Speaking of Wallace and début novels, Richard Rayner at The Los Angeles Times has reviewed Wallace’s first book The Broom of the System, which is being republished at the end of this month with a cool new cover by tattoo artist Duke Riley. A considered, well-written review, one which prompted me to dig out (okay, bad verb phrase choice; no unearthing involved, my Wallace volumes are neatly aligned together on a shelf in my living room) my copy of Broom. I remember reading a friend’s copy in the burning humidity of a Gainesville summer, in ’98 or ’99, reading the book in long chunks. I tried to read it again after I finishing Infinite Jest but it seemed kinda sorta goofy (albeit purposely, Pynchonesquely goofy). Anyway, Rayner’s review makes a strong case for a re-reading.

Speaking of Wallace and début novels, Richard Rayner at The Los Angeles Times has reviewed Wallace’s first book The Broom of the System, which is being republished at the end of this month with a cool new cover by tattoo artist Duke Riley. A considered, well-written review, one which prompted me to dig out (okay, bad verb phrase choice; no unearthing involved, my Wallace volumes are neatly aligned together on a shelf in my living room) my copy of Broom. I remember reading a friend’s copy in the burning humidity of a Gainesville summer, in ’98 or ’99, reading the book in long chunks. I tried to read it again after I finishing Infinite Jest but it seemed kinda sorta goofy (albeit purposely, Pynchonesquely goofy). Anyway, Rayner’s review makes a strong case for a re-reading.

And, speaking of Wallace (again), or at least using him as a crutch–I’ve almost finished Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead by Frank Meeink (“as told to” Jody M. Roy; they’ve sort of got the whole Malcolm X/Alex Haley thing going on there). So, yeah, why the Wallace segue? How to justify it? Well, reading Meeink’s story, the true story of an abused, battered Philadelphia kid who falls into the American neo-Nazi movement and its attendant violent crime and terrorism, who goes to prison and finds redemption and human connection and a new purpose for the nihilistic void of his life, who falls into alcoholism and drug addiction only to be redeemed again–reading Meeink’s story, even knowing its veracity (demonstrable to a point that would satisfy even Langer’s Ian Minot)–I couldn’t help but read his strong, immediate, gritty, and utterly real voice as something not unlike one of the creations in David Foster Wallace’s Brief Interviews with Hideous Men. It’s not just Meeink’s hideousness, his violence, or the grace that he works toward–all constituents of DFW’s collection–it’s that voice, the realness of the volume, surely the book’s greatest asset. Recovering Skinhead is an engrossing read, fascinating in the same way that an infected wound prompts our attention, our paradoxical compulsion and repulsion, but most of all it’s an exhilarating and exhausting performance of voice, of Meeink’s unrelenting, authentic telling of a tale, a telling that any novelist would thrill to channel. Only Meeink’s voice isn’t a novel creation: it’s real. Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead is available now from Hawthorne Books.

And, speaking of Wallace (again), or at least using him as a crutch–I’ve almost finished Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead by Frank Meeink (“as told to” Jody M. Roy; they’ve sort of got the whole Malcolm X/Alex Haley thing going on there). So, yeah, why the Wallace segue? How to justify it? Well, reading Meeink’s story, the true story of an abused, battered Philadelphia kid who falls into the American neo-Nazi movement and its attendant violent crime and terrorism, who goes to prison and finds redemption and human connection and a new purpose for the nihilistic void of his life, who falls into alcoholism and drug addiction only to be redeemed again–reading Meeink’s story, even knowing its veracity (demonstrable to a point that would satisfy even Langer’s Ian Minot)–I couldn’t help but read his strong, immediate, gritty, and utterly real voice as something not unlike one of the creations in David Foster Wallace’s Brief Interviews with Hideous Men. It’s not just Meeink’s hideousness, his violence, or the grace that he works toward–all constituents of DFW’s collection–it’s that voice, the realness of the volume, surely the book’s greatest asset. Recovering Skinhead is an engrossing read, fascinating in the same way that an infected wound prompts our attention, our paradoxical compulsion and repulsion, but most of all it’s an exhilarating and exhausting performance of voice, of Meeink’s unrelenting, authentic telling of a tale, a telling that any novelist would thrill to channel. Only Meeink’s voice isn’t a novel creation: it’s real. Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead is available now from Hawthorne Books.

The

The

(

(

First up: Adam Langer’s new novel, The Thieves of Manhattan, a send-up of the publishing industry that sets its targets directly on the current swath of (faked) memoirs that have done gangbusters for publishers in the past few years. Ian Minot is a broke-assed barista one fuck-up away from an overdue firing, who moves from the Midwest to make it as a writer in the big city. Only he’s not doing so well–in contrast to his gorgeous Romanian girlfriend Anya whose literary star is on the rise. For Minot though, this isn’t the worst–that would be the rampant success of über-poseur Blade Markham, a wanna-be gangsta whose memoir Blade on Blade is a blatant fabrication (albeit a fabrication that no one but savvy schlemiel Minot seems to notice (or, at the least, be bothered by)). I read the first fifty-odd pages of the Thieves in one sitting–a good sign to be sure. Langer’s Minot’s voice is familiar territory, the boy who loves to mock the literati he would love to be a part of. In one of the signal moves of his patois, the names of famous authors (and characters) regularly replace common nouns–a bed becomes a proust, a full head of hair is a chabon, sex is chinaski and so on. Minot seems to be headed to running his own grift soon with the help of a man he appropriately calls the Confident Man–should be good stuff. Full review forthcoming. The Thieves of Manhattan is available July 13, 2010 from

First up: Adam Langer’s new novel, The Thieves of Manhattan, a send-up of the publishing industry that sets its targets directly on the current swath of (faked) memoirs that have done gangbusters for publishers in the past few years. Ian Minot is a broke-assed barista one fuck-up away from an overdue firing, who moves from the Midwest to make it as a writer in the big city. Only he’s not doing so well–in contrast to his gorgeous Romanian girlfriend Anya whose literary star is on the rise. For Minot though, this isn’t the worst–that would be the rampant success of über-poseur Blade Markham, a wanna-be gangsta whose memoir Blade on Blade is a blatant fabrication (albeit a fabrication that no one but savvy schlemiel Minot seems to notice (or, at the least, be bothered by)). I read the first fifty-odd pages of the Thieves in one sitting–a good sign to be sure. Langer’s Minot’s voice is familiar territory, the boy who loves to mock the literati he would love to be a part of. In one of the signal moves of his patois, the names of famous authors (and characters) regularly replace common nouns–a bed becomes a proust, a full head of hair is a chabon, sex is chinaski and so on. Minot seems to be headed to running his own grift soon with the help of a man he appropriately calls the Confident Man–should be good stuff. Full review forthcoming. The Thieves of Manhattan is available July 13, 2010 from  I’ve also been reading William H. Gass’s first novel, Omensetter’s Luck. It’s weird, wonderful, Faulknerish in its loose (but somehow layered and constructed) stream of consciousness. Omensetter’s Luck comprises three sections, each progressively longer; I finished the second one today, and so far the novel seems to dance around a description or accounting of its namesake, Brackett Omensetter who carts his family into the small sleepy town of Gilean, Ohio, and immediately perplexes the townsfolk with his amazing luck. As Frederic Morton put it in his contemporary

I’ve also been reading William H. Gass’s first novel, Omensetter’s Luck. It’s weird, wonderful, Faulknerish in its loose (but somehow layered and constructed) stream of consciousness. Omensetter’s Luck comprises three sections, each progressively longer; I finished the second one today, and so far the novel seems to dance around a description or accounting of its namesake, Brackett Omensetter who carts his family into the small sleepy town of Gilean, Ohio, and immediately perplexes the townsfolk with his amazing luck. As Frederic Morton put it in his contemporary  Speaking of Wallace and début novels,

Speaking of Wallace and début novels,  And, speaking of Wallace (again), or at least using him as a crutch–I’ve almost finished Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead by Frank Meeink (“as told to” Jody M. Roy; they’ve sort of got the whole Malcolm X/Alex Haley thing going on there). So, yeah, why the Wallace segue? How to justify it? Well, reading Meeink’s story, the true story of an abused, battered Philadelphia kid who falls into the American neo-Nazi movement and its attendant violent crime and terrorism, who goes to prison and finds redemption and human connection and a new purpose for the nihilistic void of his life, who falls into alcoholism and drug addiction only to be redeemed again–reading Meeink’s story, even knowing its veracity (demonstrable to a point that would satisfy even Langer’s Ian Minot)–I couldn’t help but read his strong, immediate, gritty, and utterly real voice as something not unlike one of the creations in David Foster Wallace’s Brief Interviews with Hideous Men. It’s not just Meeink’s hideousness, his violence, or the grace that he works toward–all constituents of DFW’s collection–it’s that voice, the realness of the volume, surely the book’s greatest asset. Recovering Skinhead is an engrossing read, fascinating in the same way that an infected wound prompts our attention, our paradoxical compulsion and repulsion, but most of all it’s an exhilarating and exhausting performance of voice, of Meeink’s unrelenting, authentic telling of a tale, a telling that any novelist would thrill to channel. Only Meeink’s voice isn’t a novel creation: it’s real. Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead is available now from

And, speaking of Wallace (again), or at least using him as a crutch–I’ve almost finished Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead by Frank Meeink (“as told to” Jody M. Roy; they’ve sort of got the whole Malcolm X/Alex Haley thing going on there). So, yeah, why the Wallace segue? How to justify it? Well, reading Meeink’s story, the true story of an abused, battered Philadelphia kid who falls into the American neo-Nazi movement and its attendant violent crime and terrorism, who goes to prison and finds redemption and human connection and a new purpose for the nihilistic void of his life, who falls into alcoholism and drug addiction only to be redeemed again–reading Meeink’s story, even knowing its veracity (demonstrable to a point that would satisfy even Langer’s Ian Minot)–I couldn’t help but read his strong, immediate, gritty, and utterly real voice as something not unlike one of the creations in David Foster Wallace’s Brief Interviews with Hideous Men. It’s not just Meeink’s hideousness, his violence, or the grace that he works toward–all constituents of DFW’s collection–it’s that voice, the realness of the volume, surely the book’s greatest asset. Recovering Skinhead is an engrossing read, fascinating in the same way that an infected wound prompts our attention, our paradoxical compulsion and repulsion, but most of all it’s an exhilarating and exhausting performance of voice, of Meeink’s unrelenting, authentic telling of a tale, a telling that any novelist would thrill to channel. Only Meeink’s voice isn’t a novel creation: it’s real. Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead is available now from