In his recent essay, “Books in the Age of the iPad,” Craig Mod distinguishes between “Formless” and “Definite” content:

Formless Content is is unaware of the container. Definite Content embraces the container as a canvas. Formless content is usually only text. Definite content usually has some visual elements along with text. Much of what we consume happens to be Formless. The bulk of printed matter — novels and non-fiction — is Formless.

Mod argues that the rise of e-readers like the Kindle and (presumably) the iPad are harbingers of a new age in reading, where both formless and, now, definite content might be readily (and easily) displayed. He makes a brash judgment:

The convenience of digital text — on demand, lightweight (in file size and physicality), searchable — already far trumps that of traditional printed matter.

Really? On demand? For whom? “On demand” here presupposes a number of conditions, first and foremost, that each person who wishes to enjoy this new medium has the economic means to do so. The projected retail cost of the iPad is currently $500, a price that does not include monthly ISP fees, let alone the prices of e-books and other e-texts. The Kindle retails now for about half the price of the iPad. Although these prices will certainly fall over time, it is difficult to imagine that the “convenience of digital text” will trump equitable access to “traditional printed matter” — particularly for families with multiple children (at least any time soon).

Mod makes some good points about the future of printed, physical books in the age of e-readers (or, the iPad, a device he seems to think will normalize the medium):

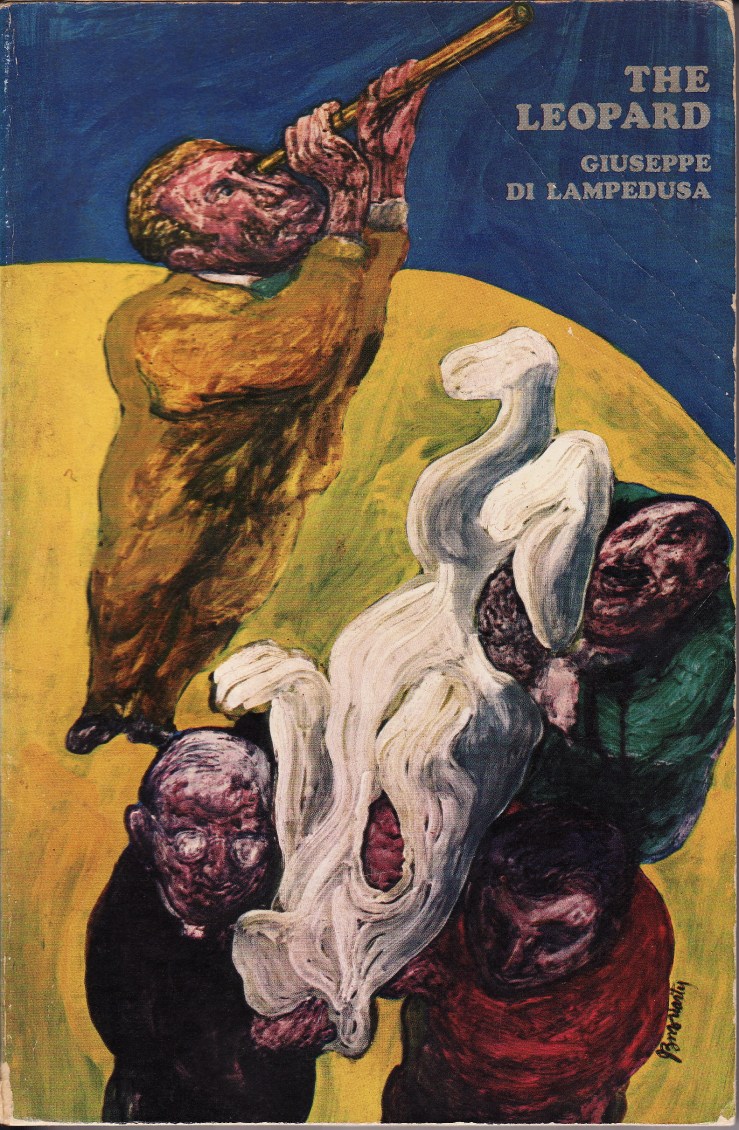

I propose the following to be considered whenever we think of printing a book:

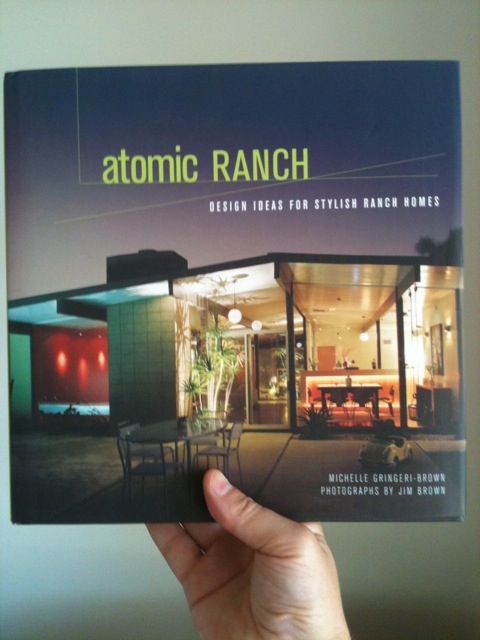

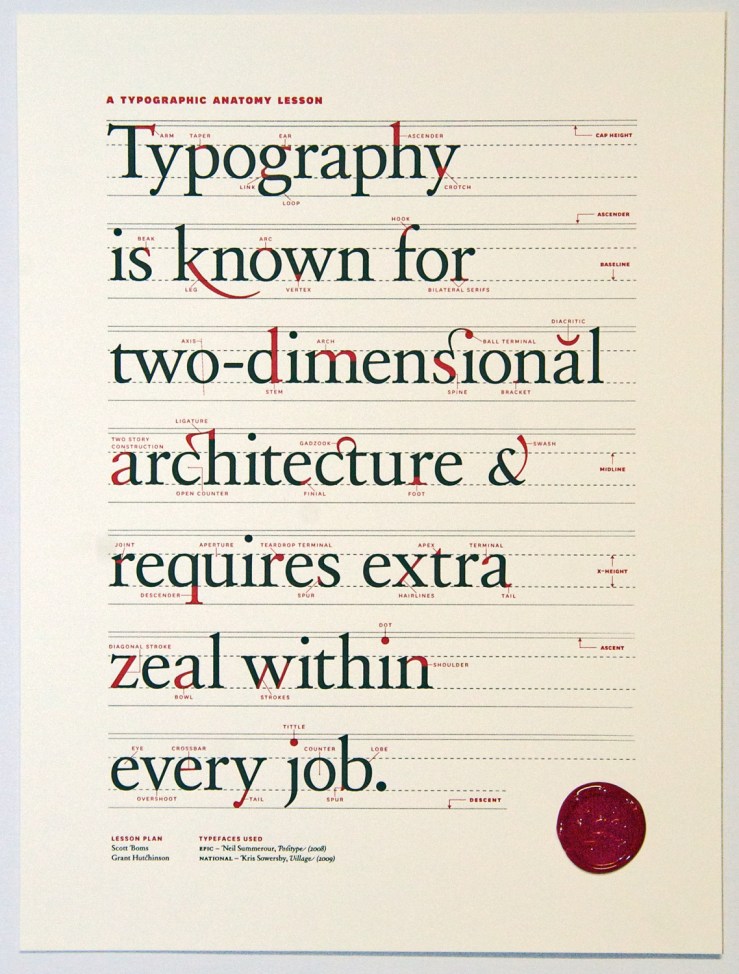

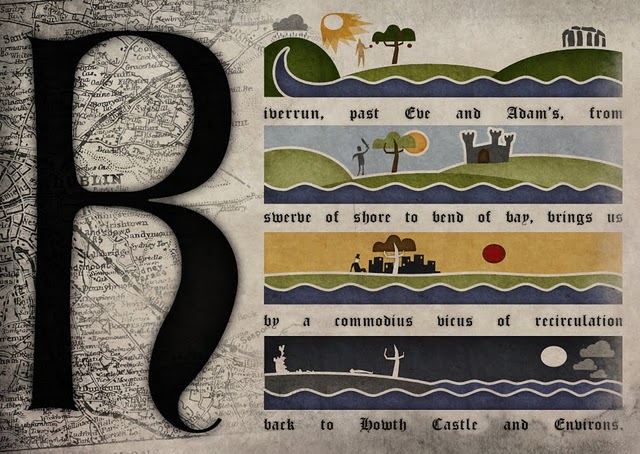

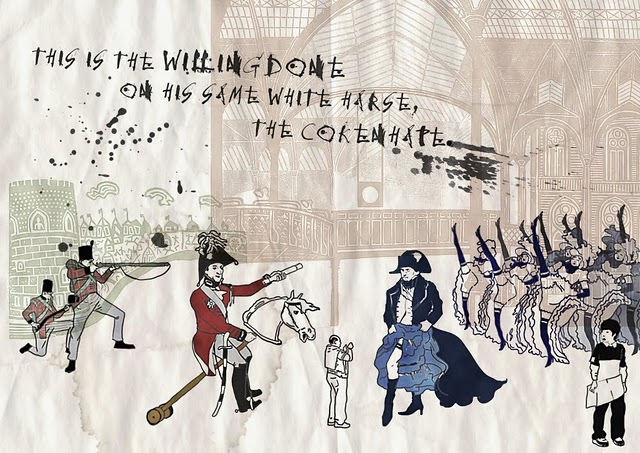

- The Books We Make embrace their physicality — working in concert with the content to illuminate the narrative.

- The Books We Make are confident in form and usage of material.

- The Books We Make exploit the advantages of print.

- The Books We Make are built to last.

The result of this is:

- The Books We Make will feel whole and solid in the hands.

- The Books We Make will smell like now forgotten, far away libraries.

- The Books We Make will be something of which even our children — who have fully embraced all things digital — will understand the worth.

- The Books We Make will always remind people that the printed book can be a sculpture for thoughts and ideas.

Anything less than this will be stepped over and promptly forgotten in the digital march forward.

Goodbye disposable books.

Hello new canvases.

Books as aesthetic, durable objects — great idea. But books as relics, as things to recall the smell of “now forgotten, far away libraries”? Really? Libraries function as an important space in communities that transcend the mediums of information in those libraries. It’s almost downright scary to posit some kind of project-utopia where a library becomes “digitized.” Also — and again, much of what Mod suggests here is great — but also, who are “our children” who “have fully embraced all things digital”? In the current geopolitical climate, Mod’s line of thinking can only realistically apply to “First World” countries. Even in our own beloved United States, first among the “First World,” we have difficulty feeding all of our children or funding their educations. E-readers like the iPad or Kindle could presumably do much to ameliorate the burgeoning education gap, but recent efforts haven’t gained much momentum or praise.

It’s not that I disagree with (what I perceive to be) Mod’s overall thesis — that the iPad and successive e-readers will revolutionize how we read, access, and store information. I do, however, think that his rosy-toned enthusiasm has led to a number of blind spots in his article. Why should e-readers eliminate libraries? What, exactly, are “disposable books”? Who will have access to these “new canvases,” and in what capacity? Why the implicit presumption that digital storage of media is fail safe, easier than current methods, and more permanent?

Finally, my biggest problem with the piece is the simple assumption that any e-reader could be more comfortable than a paperback book. Mod addresses arguments like mine:

When people lament the loss of the printed book, this — comfort — is usually what they’re talking about. My eyes tire more easily, they say. The batteries run out, the screen is tough to read in sunlight. It doesn’t like bath tubs.

Mod responds to these arguments:

Important to note is that these aren’t complaints about the text losing meaning. Books don’t become harder to understand, or confusing just because they’re digital. It’s mainly issues concerning quality. One inevitable property of the quality argument is that technology is closing the gap (through advancements in screens and batteries) and because of additional features (note taking, bookmarking, searching), will inevitably surpass the comfort level of reading on paper.

While Mod’s point of meaning vs. quality (what I’d refer to as readability) is certainly right, his assumption that technology “will inevitably surpass the comfort level of reading on paper” is wholly unfounded and unsupported. It’s exactly the kind of teleological claim we see too often about technology — that technology always progresses to an inevitable, good, and superior end point. Still, Apple can feel free to send me an iPad and I’ll be sure to test my own assumptions on the issue, and redress them here if need be.

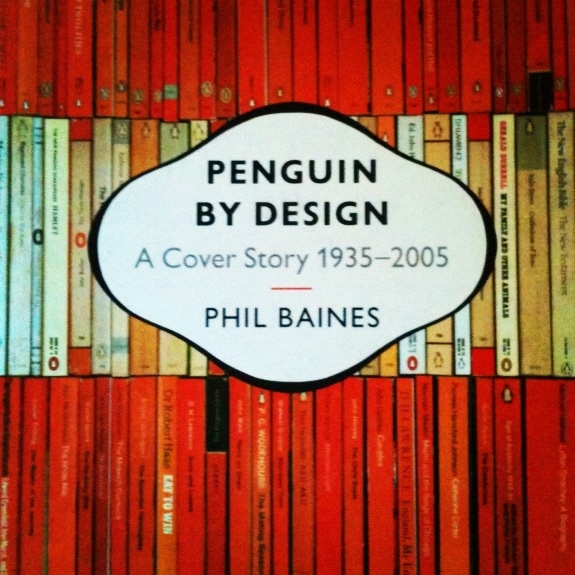

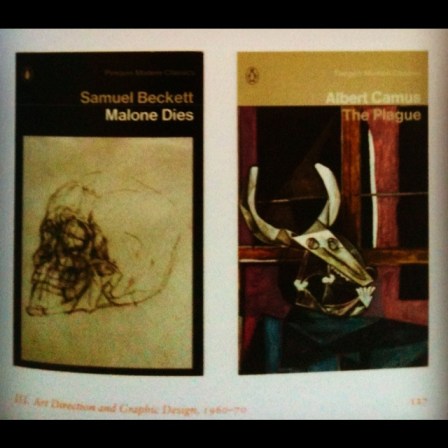

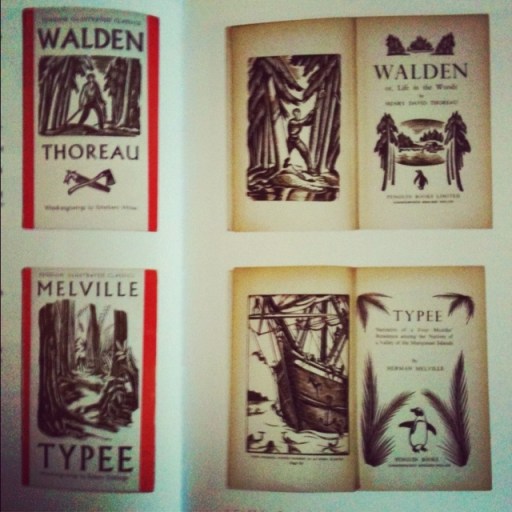

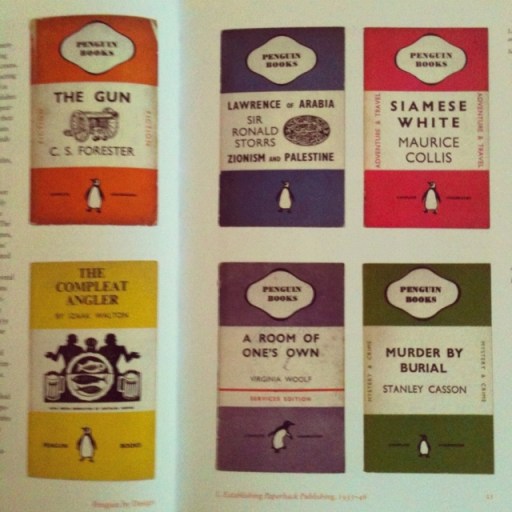

Penguin Books turns 75 today. Happy birthday! More

Penguin Books turns 75 today. Happy birthday! More