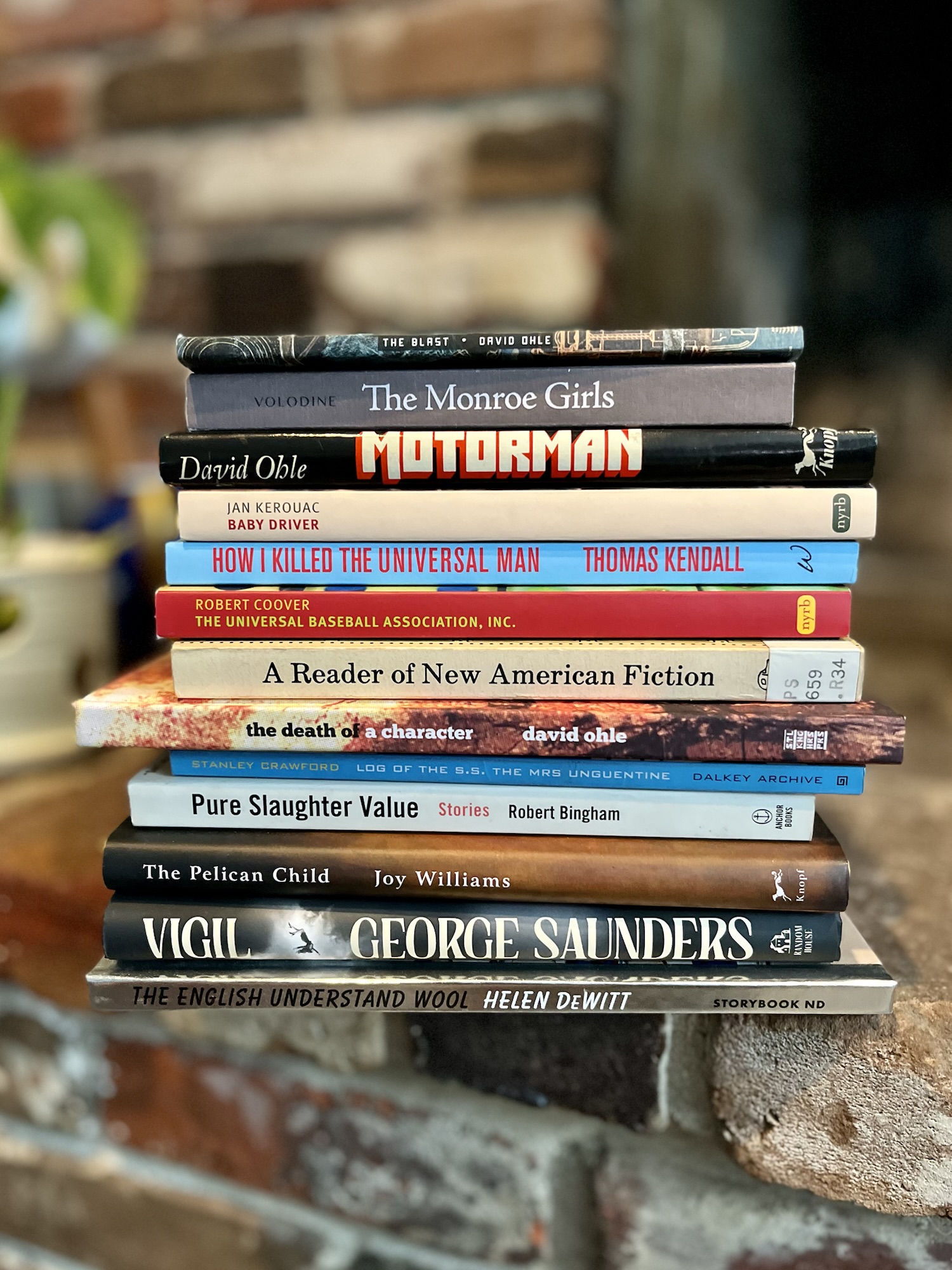

Joy Williams’ collection The Pelican Child was the first book I read this year. I picked up a copy back in December and surprised myself by reading most of it over a few days. It’s a much heavier collection than the wry vignettes of 2013’s Ninety-Nine Stories of God or its sequel, Concerning the Future of Souls (2024). The stories here alight on mortality, human ecological cultural aesthetic, etc. Opener “Flour” strikes me as a postmodern riff on Emily Dickinson’s “Because I Could Not Stop for Death” and the fable (literally fabulous?) closer “Baba Yaga and The Pelican Child” made me tear up a little and then hate myself a little. A book about death where young people, tattooed with the lines of long-dead poets, are the clean-up crew working the night shift sweeping up the detritus of the 21st century. (It was “Argos,” about Odysseus’s good and loyal boy, that really killed me if I’m honest.)

There are still a few stories at the back of Robert Bingham’s 1997 collection Pure Slaughter Value. I will tuck them away for another time. I loved these stories and then I found myself angry at his spoiled clever preppy narrators. “The Other Family” is one of the better stories I’ve read in a long time.

I reread Robert Coover’s second novel, The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., J. Henry Waugh, Prop. (1968), back in January and made some notes for a review. This is not that review. I am not a Coover expert but I think this is as good an introduction to his novels as anything. (No it’s not; get Pricksongs & Descants.)

Speaking of Universal—I had an early misfire with Thomas Kendall’s 2023 novel How I Killed the Universal Man, but then started it again the other night with a perhaps clearer idea of what the author was trying to do. I think I was thinking something more straightforward, more cyberpunknoir, something less, I dunno, formally meta or post. More thoughts to come.

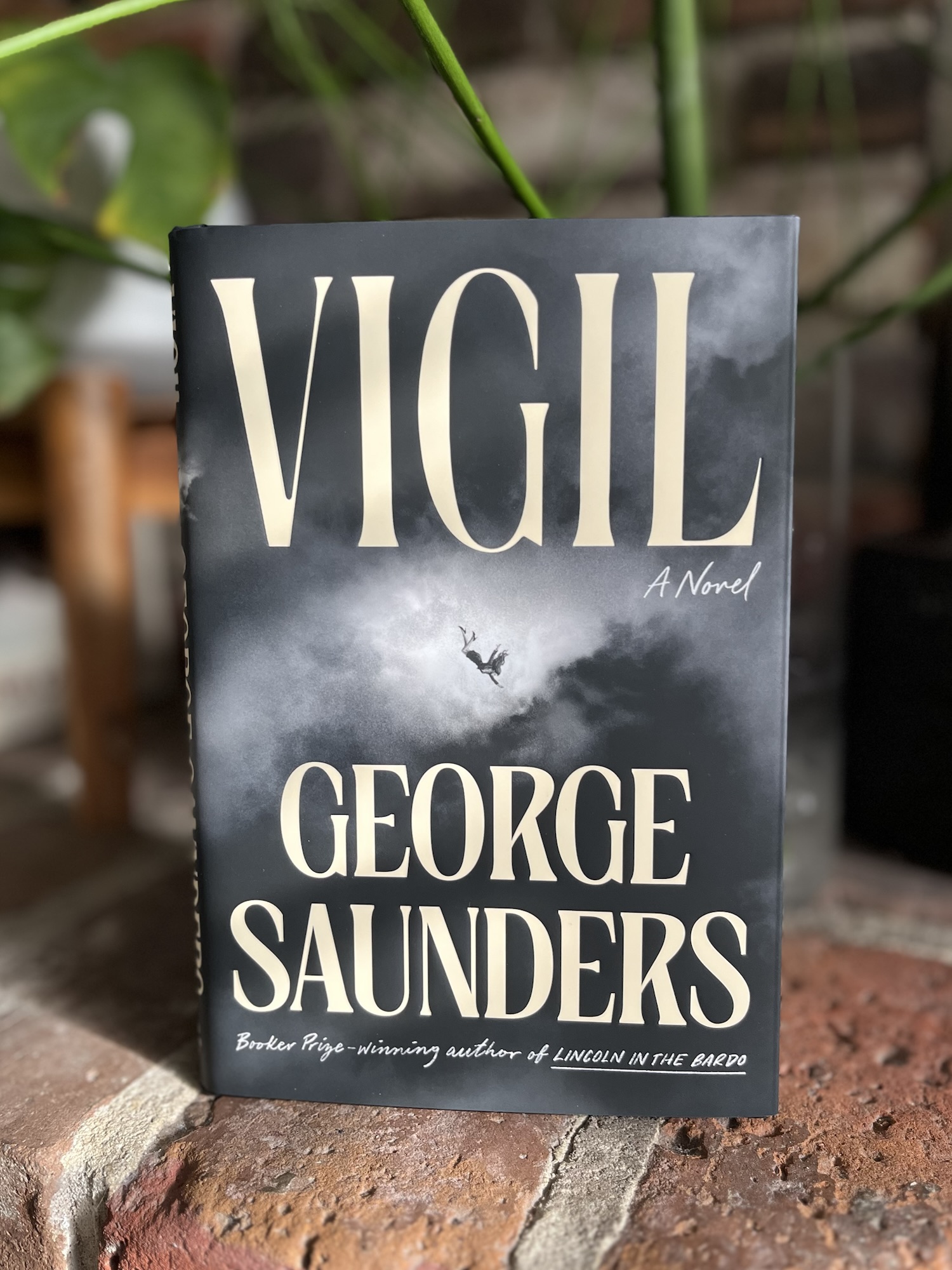

I think George Saunders’ new novel Vigil fucking sucks.

Is Helen DeWitt’s The English Understand Wool a novella? A novelette? A short story? Should we care? I loved The Last Samurai (2000), thought Lightning Rods (2011) seemed like a novel written quickly for money, and found myself embarrassed for everyone involved with her collection Some Trick (2018), including the editor, publisher, bookseller who sold it to me, and myself — but maybe I should go back and try it again? I thought The English Understand Wool was really good! It was funny and silly and sharp.

I have spent the past few months reading what I could get my little pink hands on of David Ohle’s incredible post-apocalyptic comedy, the Moldenke Saga (a term I have just now coined, maybe). I will do a Whole Thing on these novels at some point, but I read The Blast in one night and felt really sad that it was over and then the next night I read most of the last Moldenke novel, The Death of a Character, and then I woke up around 4am that morning and finished it and got a little choked up. In novels like Motorman, The Age of Sinatra, and The Old Reactor, Ohle has given us a fittingly grotesque, grody, gnarly, abject, hilarious, zany, and emotionally-resonant zombie funhouse mirror for our own gross times. These novels are woefully underread and still, for the most part, in print. Seek them out.

Wanting to scratch an Ohle itch, I turned to Literature Map to suggest some proxy; this machine offered Stanley Crawford as a proximal prosist. I picked up a few of his novels the other weekend, including 1972’s Log of the S.S. The Mrs Unguentine, which I read over the course of a few hours late at night and then reread the next night. It’s not like the Ohle oeuvre, excepting that it’s wholly, utterly original at the conceptual aesthetic rhetorical level, is generally tragicomical, mythical, epic — but also compact, and funny and alarming. So it’s very much in the Ohlesphere. Seek it out.

And also scratching that apocalyptic itch is Antoine Volodine’s 2021 novel The Monroe Girls (in translation by Alyson Waters). It’s got this cracked bifocal Bardo thing going on, which I will not explain here and now. The print in the Archipelago edition is small for my aging eyes. I’ve read it in the afternoon; it is not an afternoon book, it is a 2am book.

I read the first half of Jan Kerouac’s “semi-autobiographical” novel Baby Driver (1981) last night. The writing immediately struck me as very bad, very overwritten, ostentatious and clumsy, but I kept going, charmed by the charmingly charming naivety of the novel, which is not a naive novel at all, which turns into a rough and ready sex and drug novel, or sex and drug autobiography, or autofiction. (My instinct is that this is an autobiography with a lot of whoppers.) Our heroine is on heroin pretty quick, then turning tricks, then on to other adventures. But there’s a glib smudging of purple prose over any would-be tragic contours. She likes it! She really likes it! At least I think.

And yes, J. Kerouac is J. Kerouac’s only (acknowledged) child, and yes, he pops in now and then, a jolly fibbing wino, the poseur some of us always pegged him for, maybe a better phrase-turner than lil Jan, but somehow I think less real.

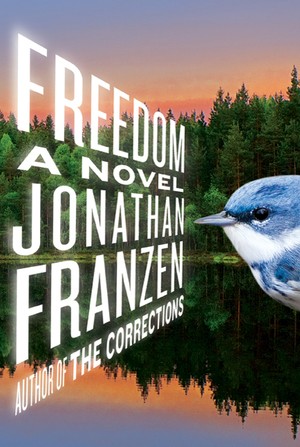

So, Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom is out today. The follow-up to 2001’s The Corrections was already in a second printing before its release today, pretty much pointing to the book being “the literary event” of 2010 (whatever that means). I haven’t read Freedom yet so I don’t have an opinion about it–but it’s hard to not have an opinion about the opinions about Freedom, at least if you follow literary-type news. The

So, Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom is out today. The follow-up to 2001’s The Corrections was already in a second printing before its release today, pretty much pointing to the book being “the literary event” of 2010 (whatever that means). I haven’t read Freedom yet so I don’t have an opinion about it–but it’s hard to not have an opinion about the opinions about Freedom, at least if you follow literary-type news. The