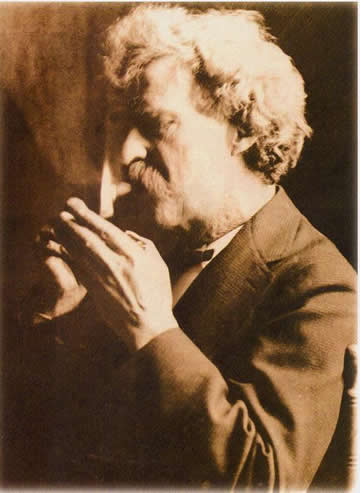

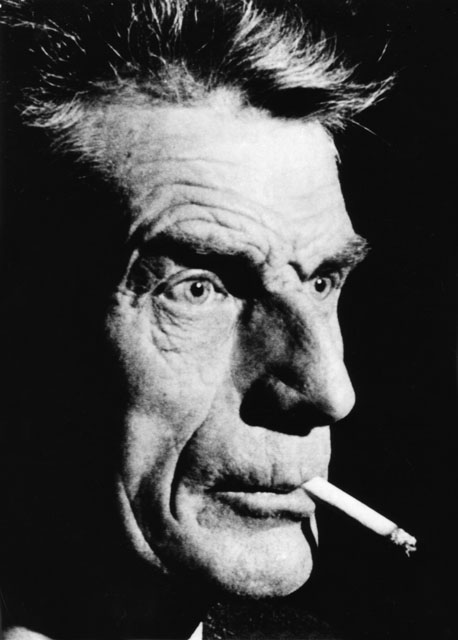

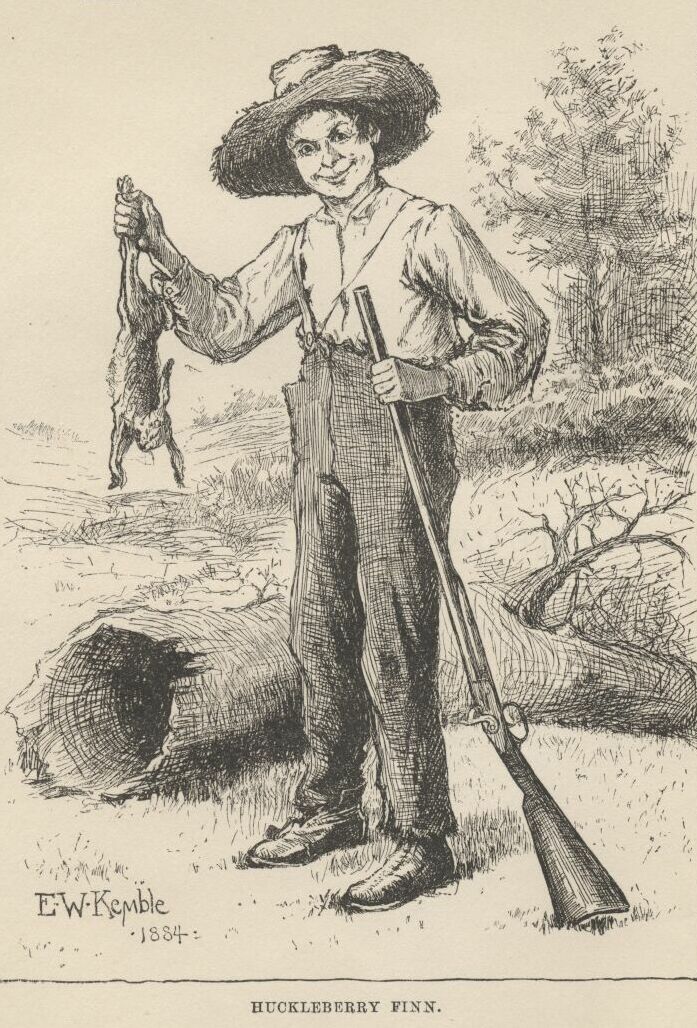

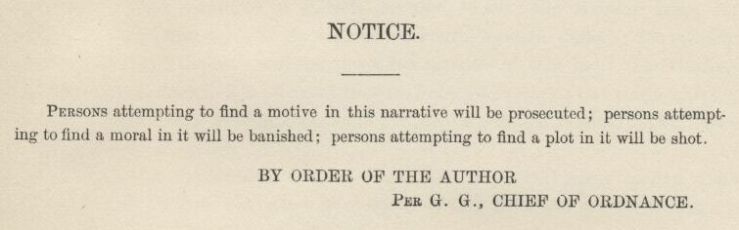

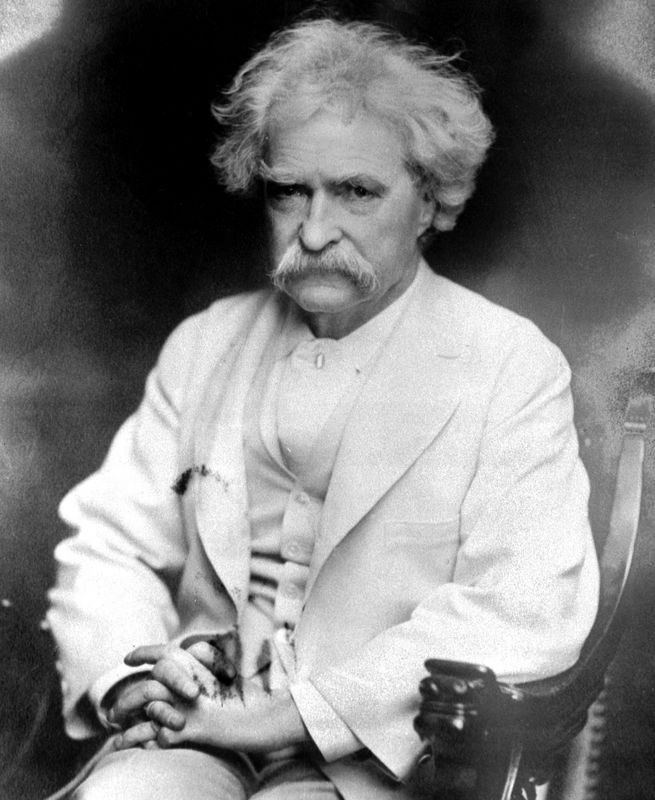

The mighty Mississippi River remains perhaps the signal geographical symbol of the United States of America. It divides our country neatly into East and West, flowing down from the industrial North to the agricultural South, and in this sense, the Mississippi is the major artery of America’s heart. We find in the Mississippi a rich mythos, one that both informs and reflects our national character. And while plenty of writers have striven to capture and express the river’s culture and character, it is Mark Twain who more or less invented our idea of the Mississippi. In his fascinating new history Wicked River, Lee Sandlin observes that, “There is a pretty much universal idea that Twain has a proprietary relationship to the Mississippi. It belongs to him, the way Victorian London belongs to Dickens or Dublin belongs to Joyce.” Sandlin’s goal in Wicked River is not to wrest the Mississippi from Twain; rather, he aims to show us the gritty turbulence swelling under Twain’s romantic myth–a myth that many Americans have come to hold as a received truth. Sandlin points out that Twain’s “Mississippi books are works of memory, even of archaeology”; they point to a vibrant river culture in a prelapsarian past, one “with its own culture and its own language and its own unspoken rules.” Sandlin’s own book plumbs that culture, revealing strange, wild tales of river pirates and con-men, fiddlers and gamblers, road agents and robbers, politicians and drunkards, and Indians and would-be “civilizers.” Sandlin’s canny observations come from a myriad of first-hand accounts–always the sign of a legitimate history–but Wicked River is never dry or dusty, but rather brims with vigor and intensity, whether we’re learning about the earthquakes that shook up New Madrid, the tornado that smashed Natchez, the sinking of the Sultana, or the ice floe that destroyed the St. Louis Harbor. Sandlin’s writing is concise, lively, and often wry and earthy–although always grounded in fact. (One colorful passage begins, “There was one simple explanation for the wildness of river culture: everybody was drunk”). Wicked River does a marvelous job conveying the tumultuous and eclectic history of an American frontier in the nineteenth century. Recommended.

The mighty Mississippi River remains perhaps the signal geographical symbol of the United States of America. It divides our country neatly into East and West, flowing down from the industrial North to the agricultural South, and in this sense, the Mississippi is the major artery of America’s heart. We find in the Mississippi a rich mythos, one that both informs and reflects our national character. And while plenty of writers have striven to capture and express the river’s culture and character, it is Mark Twain who more or less invented our idea of the Mississippi. In his fascinating new history Wicked River, Lee Sandlin observes that, “There is a pretty much universal idea that Twain has a proprietary relationship to the Mississippi. It belongs to him, the way Victorian London belongs to Dickens or Dublin belongs to Joyce.” Sandlin’s goal in Wicked River is not to wrest the Mississippi from Twain; rather, he aims to show us the gritty turbulence swelling under Twain’s romantic myth–a myth that many Americans have come to hold as a received truth. Sandlin points out that Twain’s “Mississippi books are works of memory, even of archaeology”; they point to a vibrant river culture in a prelapsarian past, one “with its own culture and its own language and its own unspoken rules.” Sandlin’s own book plumbs that culture, revealing strange, wild tales of river pirates and con-men, fiddlers and gamblers, road agents and robbers, politicians and drunkards, and Indians and would-be “civilizers.” Sandlin’s canny observations come from a myriad of first-hand accounts–always the sign of a legitimate history–but Wicked River is never dry or dusty, but rather brims with vigor and intensity, whether we’re learning about the earthquakes that shook up New Madrid, the tornado that smashed Natchez, the sinking of the Sultana, or the ice floe that destroyed the St. Louis Harbor. Sandlin’s writing is concise, lively, and often wry and earthy–although always grounded in fact. (One colorful passage begins, “There was one simple explanation for the wildness of river culture: everybody was drunk”). Wicked River does a marvelous job conveying the tumultuous and eclectic history of an American frontier in the nineteenth century. Recommended.

Wicked River is new in hardback this month from Pantheon.