If you missed this morning’s interview on NPR with Dave Tompkins on his new book How to Wreck a Nice Beach (Melville House) you can listen to it here. Tompkins discusses national defense, A Clockwork Orange, Kraftwerk, hip-hop, and autotune. Good stuff.

If you missed this morning’s interview on NPR with Dave Tompkins on his new book How to Wreck a Nice Beach (Melville House) you can listen to it here. Tompkins discusses national defense, A Clockwork Orange, Kraftwerk, hip-hop, and autotune. Good stuff.

Tag: Music

Rock and Roll Will Save Your Life — Steve Almond

Rock and Roll Will Save Your Life, Steve Almond’s new memoir-via-music-journalism, is far fresher, funnier, and insightful than its dopey name or silly cover will attest. Not that Rock and Roll Will Save Your Life is a wholly terrible name (even presented in cruciform arrangement), or that the unironic waving of lighters in the air is an awfully hokey image–but both seem counter-intuitive to the playful, self-deprecating spirit of Almond’s book. I suppose that the publisher wants to highlight a rock-as-religion motif that kinda sorta exists in the book (further compounded by the pull-quote from Aimee Mann: “Required reading for all us fans and musicians who belong to the Church of Rock and Roll”). Almond’s book is, I suppose, about being religious about music–that is, about being fanatical, crazy, bonkers about music. He calls these people–he is Exhibit #1, of course–Drooling Fanatics, or DFs for short. Drooling Fanatics are

. . . wannabes, geeks, professional worshippers, the sort of guys and dolls who walk around with songs ringing in our ears at all hours, who acquire albums compulsively, who fall in love with one record per week minimum and cannot resist telling other people–people frankly not interested–what they should be listening to and why and forcing homemade compilations into their hands and then calling them to see what they thought of these compilations, in particular the syncopated handclaps on track fourteen.

You might know some Drooling Fanatics; I know many of them. In fact, I have some DF-tendencies myself that I manage to keep in check. It’s this keen sense of self-awareness–geek-awareness–that makes Almond’s memoir so charming and engaging, particularly when he’s recounting interviews and experiences with obscure also-rans like Nil Lara, Bob Schneider, and Joe Henry. Almond’s devotion to these lesser-known artists permeates his text. His Drooling Fanaticism makes a great case for their music and even as he rants that they didn’t gain the fame and superstardom they surely deserve, he also admits that part of the Drooling Fanatic’s love for his or her artist is the special love of knowing something the rest of the world doesn’t know. Not that Almond doesn’t have various run-ins with famous people. An interview with Dave Grohl leads to Almond’s epiphany near the end of the book that being a good father and husband, doing your job to the best of your ability, and engaging fully in your own life is more important than the illusion of fame or “artistic integrity.”

Yes, “epiphany” is right–Almond’s memoir manages to avoid most pitfalls of that genre, but it still follows a recognizable arc, right up to a moment of insight and maturation. Almond punctuates this loosely-chronological framework with lists that claim to take the piss out of rock critics (who notoriously love to make lists) but, are, of course, lists. They don’t add anything to the book and they will certainly date it, and Almond’s entire chapter of lists of rock star kid names is mildly amusing but ultimately distracting. Far more successful are the “Reluctant Exegesis” sections of the book, where Almond interprets the lyrics of swill like Toto’s “Africa” and Air Supply’s “All out of Love” (he finds shades of Heidegger in the latter). These tongue-in-cheek exercises show Almond’s humorous tone as well as his skill as a critic; they also fit neatly into his memoir, contributing to the narrative proper.

Almond’s book is refreshing, both as a memoir and as a form of rock criticism. Music critics and memoirists alike are far-too often self-serious, even solemn about their work. Almond’s memoir reveals that the coolness meant to exude from many modern music critics is really an overt symptom of Drooling Fanaticism, a pose meant to close (or at least reconcile) the gap between artist and reviewer. Almond fills that gap with heartfelt joy, and, best of all, he achieves the real job of any music critic–he makes you want to listen to the stuff he’s writing about for yourself. Recommended.

Rock and Roll Will Save Your Life is available April 13 from Random House.

Let’s Not Be Pretentious

Mónica Maristain interviewing Roberto Bolaño, collected in Roberto Bolaño: The Last Interview:

MM: John Lennon, Lady Di, or Elvis Presley?

RB: The Pogues. Or Suicide. Or Bob Dylan. Well, but let’s not be pretentious: Elvis forever. Elvis and his golden voice, with a sheriff’s badge, driving a Mustang and stuffing himself with pills.

Christmas in the Heart — Bob Dylan

When Bob Dylan’s Christmas in the Heart came out a few months ago, most critics obsessed over the ironic possibilities of a Bob Dylan Christmas album, especially one called Christmas in the Heart, especially one with that cover. Had these critics forgotten that Dylan has always held his cards tight to his chest? That he’s been producing his albums for years now under the kinda-Christmasy pseudonym Jack Frost? That he only does what he really wants to do? For many of these critics, the fact that all proceeds of the album go to Feeding America functioned almost as an excuse for (more) weird behavior from Dylan. All one has to do, of course, is simply listen to the music to find that Christmas in the Heart is a minor masterpiece in the Christmas music genre and a wonderful, strange fit in the Dylan canon.

Dylan tackles fifteen carols and classics in a consistent, old-timey style evocative of Les Paul and Mary Ford and other hybrid Country & Western of the immediate post-WWII era. Dylan’s production is warm and simple, showcasing the talent of his players and backup singers. Opener “Here Comes Santa Claus” sets a lively pace that slows down over the course of the album’s first side, through a lush “Do You Hear What I Hear?” to a version of “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” that wrangles just the right mix of bitter and sweet. Dylan’s version of “Little Drummer Boy” is downright ethereal. The album picks up again with its only barnburner, a fired-up version of Lawrence Welk’s polka, “Must Be Christmas.” Do yourself a favor and enrich your life by watching the marvelous video (seriously watch it, if for nothing else than for Dylan’s surreal wig):

The energy and strange, chaotic madness of “Must Be Christmas” makes for the lively climax of the album, and the video clearly represents Dylan’s vision of Christmas as carnival. Not that it’s all ritual madness, of course. The commercial/spiritual paradox of Christmas comes out in the end, as the record winds down with the secular melancholy of “The Christmas Song” followed by the stirring hymn “O’ Little Town of Bethlehem.” If there’s any concern that Dylan is somehow not entirely earnest in his Christmas music–or too earnest in his irony, perhaps–one simply has to listen to the spirit in his gravelly, aging voice. Christmas in the Heart may be ironic, but that shouldn’t diminish its pleasures at all: it’s a self-conscious, loving irony, far from sneering, and certainly not a trick on the listener. It’s a gift of music, really (as corny as that sounds), one that asks the reader to laugh along with it, but also to feel genuine sentiment in the beauty here. Highly recommended–especially on 180 gram vinyl (the vinyl addition includes the album on CD and a 7″ single of “Must Be Christmas” and a B-side of Bob reading “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas” with backing music by John Fahey).

Best of the Aughties

So, this is Biblioklept’s 500th post [pauses for applause].

Thank you, thank you. To mark the special occasion, we’ve artfully and scientifically compiled a list of the best stuff of the aughties (or 2000s, or whatever you want to call this decade that’s ending so soon). We know the year’s not over yet, and we readily admit that our list is incomplete: we didn’t read every book published in the decade, listen to every record, watch every film, etc. So, feel free to drop a line and let us know who we forgot (or, perhaps, snubbed).

Here, in no particular order, is the best of the past decade:

Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, Children of Men, The Fiery Furnaces, The Wire, Kill Bill, Sen to Chihiro no Kamikushi (Spirited Away), The Believer, Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy, Beyoncé’s “Single Ladies” (and its marvelous video), David Foster Wallaces’s essays in Consider the Lobster, Denis Johnson’s Tree of Smoke, Animal Collective, Barack Obama, Terrence Malick’s The New World, Mad Men, Deadwood, Dave Chappelle, Curb Your Enthusiasm, Mitch Hedberg, R. Kelly, YouTube, Drag City Records, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, Nathan Rabin’s “My Year of Flops,”

Chris Adrian’s The Children’s Hospital, Extras, Harry Potter on Extras, Dave Eggers’s A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, Missy Elliott’s “Get Ur Freak On,” Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love, Pixar movies–especially the latest three: WALL-E, Up, and Ratatouille, McSweeney’s #13 (the Chris Ware Issue), Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth, that time the Shins were on Gilmore Girls, the first six episodes of The OC, Arrested Development, Nintendo Wii, Andre 3000’s “Hey Ya!,” The Office, Will Ferrell, Bob Dylan’s Theme Time Radio Hour, Picador Books, Donnie Darko,

Veronica Mars, The Venture Brothers, Home Movies, the third Harry Potter movie, Wikipedia, Bob Dylan’s Chronicles, Jonathan Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude, DFW’s Oblivion, especially “The Suffering Channel,” Wallace’s 2005 Kenyon commencement address, Wonder Showzen, Toni Morrison’s A Mercy, the totally goofy but totally fun troubadour sequence from Gilmore Girls with Yo La Tengo, Thurston, Kim, and daughter Coco Haley, and Sparks jamming, OutKast’s Stankonia, Pan’s Labyrinth, The Devil’s Backbone, The Orphanage, Cat Power’s “Willie Deadwilder,”Flight of the Conchords, Girl Talk’s Night Ripper, The Daily Show with John Stewart, The Colbert Report,

Andy Samberg’s Digital Shorts, Autotune the News, Tim Tebow, Panda Bear’s Person Pitch, Nels Cline’s guitar solo in “Impossible Germany,” Judd Apatow, Be Kind Rewind, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Thrill Jockey Records, I Heart Huckabees, Chris Bachelder’s U.S.!, David Lynch’s INLAND EMPIRE, Fennesz’s Endless Summer, Gmail, the Coens’ No Country for Old Men, MF Doom (all iterations), Broken Social Scene’s You Forgot It in People, Satrapi’s Persepolis, UGK’s “International Player’s Anthem,” Bob Dylan’s “Things Have Changed,” Bonnie “Prince” Billy,

The Silver Jews’ Tanglewood Numbers, lolcatz, Once, Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, the Coens’ O Brother, Where Art Thou?, web two point oh, 30 Rock, Belle & Sebastian’s “Stay Loose,” It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, Philip Pullman’s The Amber Spyglass, Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man, WordPress, Jim O’Rourke’s Insignificance, the first season of Battlestar Galactica, Superbad, half a dozen or so short stories by Wells Tower, David Cross’s Shut Up, You Fucking Baby!, Drunk History, the action sequence at the end of Tarantino’s Death Proof (and especially the joyous, headcrushing final shot), Slavoj Žižek’s Violence, The Royal Tennenbaums, the first 20 minutes of Gangs of New York,

Firefox, the increasing and continuing availability of English translations of authors like Roberto Bolaño and W.G. Sebald, Bill Murray, Margot at the Wedding, Rachel Getting Married, Top Chef, The Dirty Projector’s Bitte Orca, Battles’ “Atlas,” Revenge of the Sith, Sarah Vowell, Art Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers, Christoph Waltz’s bravura performance in Inglourious Basterds, the surreal animations of Carson Mell, Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake, Tina Fey’s impression of Sarah Palin, David Mazzucchelli’s Asterios Polyp, Neko Case’s “Star Witness,” Jason Statham, The Pirate Bay, HDTV, Charles Burns’s Black Hole, &c . . .

Bicycle Diaries – David Byrne

David Byrne’s new book, Bicycle Diaries (new in hardback from Viking), is an engaging, discursive, and often meditative memoir about the Talking Heads founder’s strange experiences bicycling through some of the world’s most distinct cities. Byrne uses W.G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn (one of our favorite books) as an entry point for his book. Like Sebald, Byrne attempts to synthesize history, memory, art, architecture, philosophy, science, and a host of other subjects in his writings on cities like Berlin, London, Manila, Istanbul, and San Francisco. The result is a book that is profound and very readable; Byrne communicates complex ideas in ways that are both fun to read and also highly relevant to an age of changing attitudes about how we are to get where we are going.

While hardly a political screed, Bicycle Diaries does contain a central argument: plainly put, Byrne suggests that cities that are bicycle-friendly tend to be more human-friendly, and that the modern/industrial reliance on cars and trucks has resulted in fundamental disconnects between people and their communities. In the first chapter, “American Cities,” Byrne surveys a number of decidedly unglamorous American cities like Pittsburgh, Baltimore, and Columbus, as well as smaller towns like Sweetwater, Texas. Byrne’s discussion of Detroit is particularly affecting. From the vantage of his bicycle, Byrne sees a Detroit most will miss, a place of modern ruins and decay. “In a car, one would have sought out a freeway, one of the notorious concrete arteries, and would never have seen any of this stuff,” Byrne writes. “Riding for hours right next to it was visceral and heartbreaking–in ways that looking at ancient ruins aren’t. I recommend it.”

Byrne repeatedly communicates this will to immediacy, for unmediated experiences in Bicycle Diaries. He’s the explorer of the real, trying to understand why folks don’t ride bikes in Buenos Aires, or trying to figure out the cultural significance of Imelda Marcos to the people of the Philippines, or pondering the brutal fauna of Australia. Byrne’s bike rides, as well as his music and art careers, give the book something like a center, but Bicycle Diaries thrives on digressions, asides on ring tones or the Stasi or amateur backyard wrestling or the history of PowerPoint. We loved these moments: it’s when Byrne relates the sad history of George Eastman, founder of Kodak, or when he tells the story of Australian outlaw legend Ned Kelly that Byrne best communicates the thrill of exploration.

Byrne’s voice is ever-earnest and never didactic. There’s a plainness and honesty to his delivery that often seems in direct contrast with the content of his message. And this is the key to the book’s success–and perhaps, more generally speaking, Byrne’s career–this ability to see, to suspend the biases and blocks and filters that too often mediate our perception, and to actually see what is actually around us. From his earliest days in the Talking Heads, Byrne displayed an uncanny knack for turning his eyes on his own culture like an alien ethnographer, yet he always did it with empathy and engagement, and never with smack of clinical remove that might otherwise characterize such a project. In Bicycle Diaries, Byrne approaches America’s reliance on roads and oil and cars with an admirable pragmatism. Where some might scold (and, implicitly, ride a high horse), Byrne is always positive, pointing out the numerous advantages of returning to a community-oriented way of life, with bicycling as a simple and efficient means of getting around in lieu of the cars–and attendant urban/suburban/exurban sprawl–that keep us separated. Byrne also suggests a number of ways that communities and cities can work toward making bicycling a more viable option for their citizens. He even provides a few fun bicycle rack designs for his hometown New York (and yes, they got made).

Finally, we’d be remiss if we didn’t mention that the book itself is a beautiful aesthetic object. Why don’t more publishers skip those annoying, flimsy dust jackets, and opt instead for something like Bicycle Diaries lovely embossed cloth deal? Just a thought. There are lots and lots of black and white photographs, many by Byrne himself, that genuinely shed light on Byrne’s narrative (the design here is of course reminiscent of Sebald’s use of photographs, only Byrne’s aren’t cryptic and actually make sense in the text). It’s great to love both the content and the design of a book, but we’d really expect nothing less from Byrne. It’s also great when a hero of ours lives up to and then surpasses our expectations–we’ve always loved Byrne’s music and his ideas, so it’s great that we can add books to that list. Highly recommended.

A Modern Symphony of Music that Is Not Music but Asks that You Remember Music

We are just loving the advance reading copy of David Byrne’s Bicycle Diaries that we got in the mail today. Plenty of quotable material from Byrne’s discursive journeys, but why not share one of our favorite musician’s thoughts on ring tones?

I hear the faint cacophony of many distant cell-phone rings in the train car–snippets of Mozart and hip-hop, old-school ring tones, and pop-song fragments–all emanating out of minuscule phone speakers. All tinkling away here and there. All incredibly poor reproductions of other music. These ring tones are “signs” for “real” music. This is music not meant to be actually listened to as music, but to remind you of and refer to other, real, music. These are audio road signs that proclaim “I am a Mozart person” or, more often, “I can’t even be bothered to select a ring tone.” A modern symphony of music that is not music but asks that you remember music.

The Visitor — Jim O’Rourke

After a minute of deliberate, restrained acoustic guitar phrases accompanied with a few touches of piano, Jim O’Rourke’s The Visitor unfolds suddenly into a warm, rich, full-band arrangement, humming with sinewy slide guitars and clippety-clop percussion. For ten short, gorgeous seconds, O’Rourke declares that, after having made listeners wait for over a decade for a follow up to his brilliant instrumental suite Bad Timing, he won’t delay the magic any longer. After those ten seconds, the music returns to that solitary guitar, but just a minute later, the full band is back again, establishing a rhythm that will permeate the disc.

Space, delay, and restraint have long been some of O’Rourke’s sharpest tools: fans of Bad Timing can attest to the sublime payoff in the record’s final moments, and his work in Gastr del Sol with David Grubbs often challenged audiences’ patience, rewarding them in oblique moments of beauty too strange to name. Not that O’Rourke’s music is wholly strange–in fact, I can’t think of another musician who makes recordings sound so damn good. He has an almost preternatural gift for sonic spaces, whether as a solo artist or as a producer (and auxiliary member) of groups like Stereolab and The High Llamas (or more obscure acts like Wilco and Sonic Youth). In short, we expect that a Jim O’Rourke record (a “proper” one–not one of his (many, many) forays into experimental/improvisational collaboration) will sound really fucking good. In this sense, The Visitor isn’t particularly revelatory: it’s a great-sounding, expertly-played, 38-minute suite of music. It affirms what we know about O’Rourke, and leaves us wanting more.

For a record with such a unified sound and vision, The Visitor is also paradoxically all over the place. It’s one complete track, at least in digital form, and while there are clearly discrete passages, it’s nearly impossible to find where they might distinctly begin or end. Unlike its most obvious predecessor, Bad Timing, an album divided into four tracks, there are no seams showing here. Neither is there any reliance on electronic trickery or production shenanigans (which O’Rourke followers know he could pull off standing on his head). The Visitor is pure musicianship, full of resonant organs, lovely acoustic guitars, and a host of other instruments in the Americana vein that O’Rourke so clearly cherishes (it’s impossible not to hear nods to heroes of his like Van Dyke Parks and John Fahey here, of course). There are amazing moments, like at 11:25 or so when O’Rourke channels Dickey Betts for a killer micro-solo, or does a Brian May send-up at 20:40. There are woodwinds, there are banjos, there are instruments working together that I cannot identify. And it all sounds very, very good.

Undoubtedly, The Visitor will have its detractors. Unlike O’Rourke’s 1999 pop masterpiece Eureka, it is not an album of songs to know and love; neither is it remotely close to 2001’s more aggressive Insignificance. It is, as I’ve stated a few times now, a single suite of instrumental music, perhaps too pleasant for some or too weird for others. And while I’m very enthusiastic about it–I’ve listened to it about 25 times over the past three days–I admit that it also whets my appetite for a follow-up to O’Rourke’s more pop-oriented records. I’d love to hear the guy’s imperfect voice sing those mean, mean lyrics again. And I hope he won’t make us wait another eight years for one. Final verdict: buy The Visitor, listen to it, love it.

Jim O’Rourke’s The Visitor is available September 8th, 2009 from Drag City (who will mail it to you postage-paid for a mere $14 vinyl, $12 CD) or your favorite record store.

The Music of Pynchon’s Inherent Vice

Thomas Pynchon‘s latest novel, Inherent Vice is loaded with musical references–the radio’s always buzzing, bands are always hammering out jams, and hero Doc Sportello is always singing a verse or two. Wouldn’t it be cool if someone would take the time to make a playlist of all the tunes in the book? Okay, that was a lame set-up. Obviously somebody did take the time, and according to the text accompanying the original list at Amazon (yeah, I’m shamelessly cutting and pasting and also saving you time), “the playlist that follows is designed exclusively for Amazon.com, courtesy of Thomas Pynchon.” Hmmmm…wonder if Pynchon made the list himself–after all, he writes his own book jacket blurbs, and he even narrated the trailer for Inherent Vice. Pretty cool. Links go to downloads (not free, sorry) or artist pages. In cases of no links, the band or artist is one of Pynchon’s original creations (although we’d really, really love to hear “Soul Gidget,” or really anything by Meatball Flag). Bonus vid after the list.

- “Bamboo” by Johnny and the Hurricanes

- “Bang Bang” by The Bonzo Dog Band

- Bootleg Tape by Elephant’s Memory

- “Can’t Buy Me Love” by The Beatles

- “Desafinado” by Stan Getz & Astrud Gilberto, with Charlie Byrd

- Elusive Butterfly by Bob Lind

- “Fly Me to the Moon” by Frank Sinatra

- “Full Moon in Pisces” performed by Lark

- “God Only Knows” by The Beach Boys

- The Greatest Hits of Tommy James and The Shondells

- “Happy Trails to You” by Roy Rogers

- “Help Me, Rhonda” by The Beach Boys

- “Here Come the Hodads” by The Marketts

- “The Ice Caps” by Tiny Tim

- “Interstellar Overdrive” by Pink Floyd

- “It Never Entered My Mind” by Andrea Marcovicci

- “Just the Lasagna (Semi-Bossa Nova)” by Carmine & the Cal-Zones

- “Long Trip Out” by Spotted Dick

- “Motion by the Ocean” by The Boards

- “People Are Strange (When You’re a Stranger)” by The Doors

- “Pipeline” by The Chantays

- “Quentin’s Theme” (Theme Song from “Dark Shadows”) performed by Charles Randolph Grean Sounde

- Rembetissa by Roza Eskenazi

- “Repossess Man” by Droolin’ Floyd Womack

- “Skyful of Hearts” performed by Larry “Doc” Sportello

- “Something Happened to Me Yesterday” by The Rolling Stones

- “Something in the Air” by Thunderclap Newman

- “Soul Gidget” by Meatball Flag

- “Stranger in Love” performed by The Spaniels

- “Sugar Sugar” by The Archies

- “Super Market” by Fapardokly

- “Surfin’ Bird” by The Trashmen

- “Telstar” by The Tornados

- “Tequila” by The Champs

- Theme Song from “The Big Valley” performed by Beer

- “There’s No Business Like Show Business” by Ethel Merman

- Vincebus Eruptum by Blue Cheer

- “Volare” by Domenico Modugno

- “Wabash Cannonball” by Roy Acuff & His Crazy Tennesseans

- “Wipeout” by The Surfaris

- “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” by The Beach Boys

- “Yummy Yummy Yummy” performed by Ohio Express

Waiting for The Visitor

We’re pretty psyched about Jim O’Rourke‘s upcoming album, The Visitor, out on Drag City September 8th. O’Rourke hasn’t put out a “pop” record (as opposed to “experimental,” something of a false dichotomy really) since 2001’s Insignificance. Apparently, the new record is in the vein of one of our all-time favorite records, 1997’s Bad Timing. Supposedly the record will take the form of one long suite of music called “The Visitor,” and according to this interview from last year, “pretty much everyone is going to be disappointed.” He also says that the new record will be “pt. 4” after Bad Timing, Eureka, and Insignificance, so it’s hard to imagine being disappointed. Here’s the (we think) Nic Roeg connection (quick note: the three albums just cited are named after Nic Roeg films): in 1976’s The Man Who Fell to Earth, David Bowie plays a space alien stranded on Earth who records an album under the name The Visitor. Here’s the cover of The Visitor:

Here’s a Eureka-era audio interview with O’Rourke that you can download. He talks about his prolific powers, the influence of Godard and Roeg on his work, hierarchy and didacticism in music, the cheesy sax solo on “Eureka” (“Of course it’s stupid!”), and why listening to music is a process of education. Good stuff. Or, if you want music, not words, here’s the sorta kinda rarity, “Never Again,” from the Chicago 2018 comp. Also good stuff.

The Spectacle of Michael Jackson’s Body

For the next few weeks, thousands, hundreds of thousands, possibly millions will remember, laud, argue over, and grieve Michael Jackson. His death, like his life, was utterly mediated–broadcast live on national television, Twittered, Facebooked. We were able to follow the accretion of details and speculations (facts?) in real time, as the status of Jackson’s body was updated (he was dead, he was rushed to the hospital, he was in a coma, no, he was dead). His death even precipitated a rush of other celebrity death notices, hoaxes that mutated across the internet. That Jackson’s death should precipitate so much confusion and rumor is commensurate with his strange life.

Jackson was probably the first person in the world to live a truly mediated life. From the age of eleven, Jackson’s image, voice, and dancing body became the communal property of the modern (industrialist, capitalist) world. Written roughly the same time as young MJ’s rise to national prominence, Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle opens with the following salvo: “In societies where modern conditions of production prevail, all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation.” What was Michael Jackson’s life but a series of transmogrified spectacular representations? Not only did we hear the development of modern music through his records, or watch fashions change through his bizarre styles, but, most significantly, we saw in Jackson a mapping of spectacle culture on to the very body itself. Like his character who mutates in the iconic “Thriller” video, or the faces at the end of his “Black or White” video, Michael Jackson’s body slowly morphed before our collective eyes, mediated in print and video, discussed and mocked and puzzled over. A full accounting of Jackson’s eccentricities is neither necessary or possible here, but it’s worth pointing out that the man’s level of estrangement was of such an acute degree that, beyond attempting to remap the world (turn it into a Neverland) and reconfigure the flow of time (an attempt to reach an imaginary past), he remapped his whole body.

While he wasn’t the first celebrity whose body became a site of/for spectacle culture (Marilyn Monroe springs immediately to mind), Jackson’s corpus is undoubtedly the signal symbol of the mediated American Dream, the most hyperbolic example how the human body might mediate consumerist desires. As Debord also pointed out in Society, “The spectacle is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images.” The death of Michael Jackson is precisely not the death of Michael Jackson’s body, which will continue to live on, like one of the “Thriller” zombies, a spectacle absorbed and batted about by the spectacle culture. It will continue to exist as a rarefied nostalgic currency, for if we grieve the death of Michael Jackson, what precisely are we grieving if not a spectacular reflection of our own (mediated) development? Michael Jackson’s body (of work) will always be resuscitated as a nostalgic marker for at least three generations of Americans (and the rest of the world, really). I do not believe that most of us mourn the death of Michael Jackson; instead, we continue to participate in his spectacle (or, rather, the spectacle of him) as a means of prolonging our own vitality and placating our own sense of self. It is not the loss of Jackson that we might acutely feel but instead a demarcation upon our own mortal bodies, for if a changeling like Jackson cannot escape bodily death, what hope do we have? At the same time, paradoxically, participating in the spectacle of the death of Michael Jackson’s body partially alleviates (even as it subtly calls attention to) these anxieties. By affording Jackson (the illusion) of a certain immortality, we retain our own developmental, life-long investments in his spectacle, and, in turn, hope to secure our own bodies against the ravages of age, disease, decay, accident, gravity.

But what are the long-term costs of maintaining such grand illusions? As our society becomes increasingly mediated, are we arcing toward a more democratic and enriching series of personal connections, or are we fragmenting and disassociating into solipsism and self-reflexivity? Or, to return to Jackson, does his music represent personal connection and the transmission and articulation of genuine sentiment, or is it simply the glamorous reduction of crass popular culture? Is it possible to feel genuine empathy toward Jackson? Or has the spectacle of Michael Jackson’s body infiltrated our culture to the point at which any real, unmediated human response to his passing become an impossibility, an articulated fiction masking narcissistic nostalgia? Although these are not intended as rhetorical questions, I don’t suppose there are simple answers for them either. Ultimately, I think as long as our spectacle society exists, Michael Jackson’s body will continue to exist. And probably, as our culture ages–and this is scary–it will become a relic or monument to a simpler time.

Good Friday

As the B-52s understood so well, we all need some good stuff in our life. Here’s some good stuff:

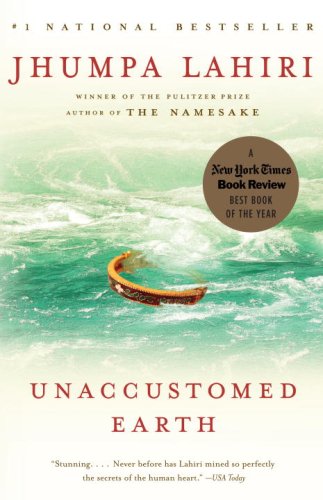

Jhumpa Lahiri’s much-lauded collection of short stories, Unaccustomed Earth, is out in paperback from Vintage this week. Although I’ve only read three of the collection’s eight stories so far, it’s already easy to see why the book was so beloved last year. Lahiri explores the intersection of different cultures and the subtleties of generational conflict, but the themes and content of her stories always veer toward universals of domesticity–siblings, marriage, children, and all the troubles that go with them are studied here. I found bits of my own life echoed here in insightful and analytical detail, particularly in the heart breaker “Only Goodness.” Good stuff.

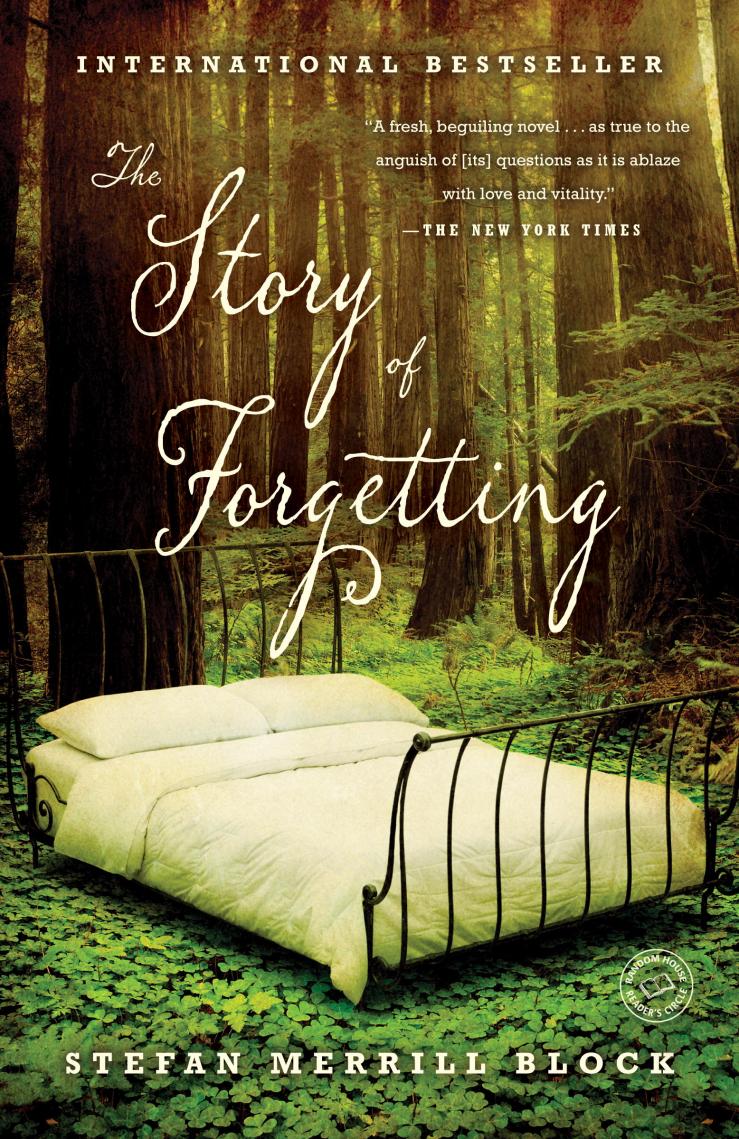

Also new in paperback this week from Randomhouse is Stefan Merrill Block’s debut novel The Story of Forgetting, and while I haven’t had a chance to get too far into it, its blend of science, medicine, memory, and fantasy seems pretty intriguing. Block examines Alzheimer’s disease through the lens of an elderly man named Abel, a misanthropic teen named Seth, and a Calvinoesque fantasy world called Isadora–a world without memory. Seems pretty cool; potential good stuff. Trailer here.

For more good stuff, check out our new tumblog Pet Zounds.

Here’s a cool interview from The Times with Bob Dylan on Presidential autobiographies and more. Good stuff.

You can also listen to all ninety minutes of Neko Case’s concert at the 9:30 club, broadcast live last night on NPR. Lovely Ms. Case transcends good stuff, of course.

Speaking of transcendent good stuff, the new Dirty Projectors album, Bitte Orca, has, ahem, leaked. It’s the sort of greatness that makes you ashamed to be a pirate, the kind of album you can’t wait to actually buy even though you’ve been listening to it in full for a few months (it doesn’t drop until June 9th). Lush and ethereal, somewhere between Kate Bush and Storm & Stress, Bitte Orca is the sort of stuff that would play at high school proms around this country this year if this country had any class. Here they are playing “Stillness is the Move”:

Zora Neale Hurston Sings “You May Go But This Will Bring You Back”

Zora Neale Hurston sings folksong “You May Go But This Will Bring You Back,” and then explains how she learns her songs. More info here.

Zora Neale Hurston Sings “Uncle Bud”

A salty song about a ribald gentleman by the name of “Uncle Bud,” whose “nuts hangs down like a Georgia bull.” Great stuff. The accompanying video footage was shot by Hurston herself on one of her trips through south Florida, where she collected the folktales and songs of rural blacks. Many of these tales–often called “lies”–are found in Hurston’s Mules and Men, a hybrid work that novelizes these narratives into a cohesive whole, an afternoon spent on a porch telling stories and singing songs. Recommended.

Strange Fruit

In cynical times, it’s far too easy to dismiss the value of the arts. But listen to Billie Holiday’s recording of “Strange Fruit.” When Holiday put Bronx high-school teacher Abel Meeropol‘s lyrics to music, she captured the bizarre pain and insanity of a legacy of lynching in the American South. Meeropol’s morbid lyrics juxtapose a “Pastoral scene of the gallant south” against the gruesome spectacle of a lynching. The “strange and bitter crop” of history–the hanging flesh of dead black men–is preserved forever in this sad and bitter elegy. Art–song and poetry–has a capability to tell an abstract truth in a way that the concrete annals of history cannot achieve.

“Strange Fruit”

Southern trees bear strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant south,

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,

Scent of magnolias, sweet and fresh,

Then the sudden smell of burning flesh.

Here is fruit for the crows to pluck,

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck,

For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop,

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

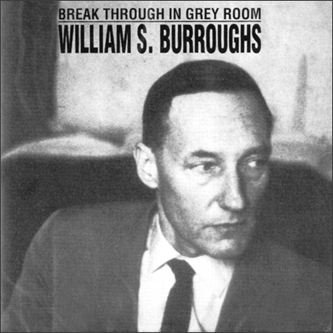

William S. Burroughs/John Giorno

Look at these guys! I kind of have to have this record. If you have a copy, go ahead and send it to me. No? Okay, what about uploading the tracks somewhere as mp3s? No? Okay…

Image and LP info via Brainwashed.

William S. Burroughs/John Giorno (1975), GPS 006-007

William Burroughs

1. “103rd Street Boys” from Junkie 2. excerpt from Naked Lunch 3. “From Here To Eternity” from Exterminator 4. excerpt from Ah Pook Is Here 5. “The Chief Smiles” from Wild Boys 6. “The Green Nun” 7. excerpt from Cities Of The Red Night

John Giorno 8. “Eating Human Meat”

And so as not to just beg for mp3s but to also give, check out Burroughs explaining how tape manipulation helps to expand conciousness in “Origin and Theory of the Tape,” and get horrified by an example of said technique with “Present Time Exercises,” both from Break Through in Grey Room, a collection of Burroughs’s tape experiments and speeches (not to mention a dash of Ornette Coleman freaking freestyle in Morocco).

The Eight Best Songs of 2008

In no particular order…

Fleet Foxes – “White Winter Hymnal”

Beyoncé (Sasha Fierce) – “Single Ladies”

Crystal Castles – “Crimewave”

Deerhunter – “Nothing Ever Happened”

Kanye West – “Love Lockdown”

Marnie Stern – “Transformer”

Max Tundra – “Will Get Fooled Again”

MIA – “Paper Planes”