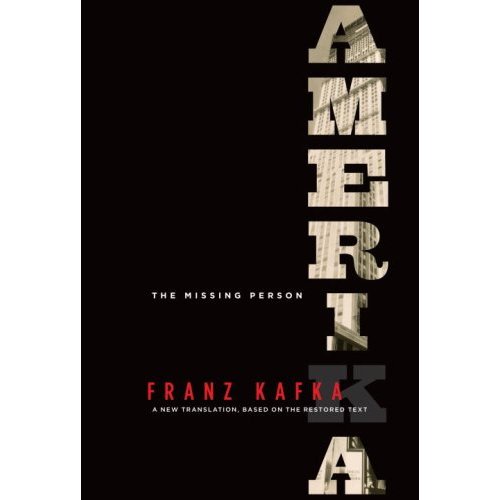

I had a (very, very minor) Kafkaesque moment when Mark Harman’s new translation of Franz Kafka’s unfinished first novel, Amerika first arrived at Biblioklept International Headquarters. Wanting to compare the style of Harman’s translation to Edwin and Willa Muir’s work, I searched for my old copy of Amerika. I figured I’d re-read the first chapter, “The Stoker,” the only part of the novel that Kafka reworked (it was published as a short story). So I looked and looked and it turns out that I don’t own Amerika, despite the obligatory Kafka phase I went through in high school (followed by a post-bac Kafka phase years later). But I knew I’d read “The Stoker,” or at least it seemed likely that I’d read “The Stoker,” and it turned up in a collection of Kafka’s short stories that I own–only it was the Donna Freed translation. So I re-read it, only I’m not sure that I was re-reading it. I didn’t remember any of it, other than the famous opening image of a Statue of Liberty armed with a sword. I’m still not sure that I ever read it before now; that is, I’m not sure that I read the Muir translation that Harman seeks to amend. I guess it doesn’t matter, and it seems appropriate that a Kafka review begin with a meandering false start. Where were we?

Yes. Harman’s translation. With Amerika, Harman continues a project he initiated with his translation of another unfinished Kafka novel, The Castle. (This book was published in 1998, and I listened to the audio book last summer, incidentally, and it was really, really good). Harman’s translations aim to restore some of the humor, ambiguity, and modernism that the Muirs’ early translations occlude in favor of their own religious readings. Harman also takes great pains to remove Max Brod’s editorial interventions, even going as far as to keep many of Kafka’s consistent solecisms (“Oklahoma” is restored to Kafka’s original – and consistent – “Oklahama”). Now, my Kafkaesque confusion over whether or not I’ve read the Muirs’ translation of Amerika prevents me from commenting here on Harman’s apparent restoration of Kafka’s humor, but I do think that Amerika is often funny, and often terrifying. Its protagonist Karl finds himself in a parallel-universe America (one constructed wholly from Kafka’s imagination, and announced in its surreal glory from the opening image of a Statue of Liberty armed with sword), one where he’s consistently misled, swindled, cornered, cramped, and generally mistreated by various enigmatic authority figures (yes, its Kafkaesque, if you’ll allow the tautology). As noted, Kafka never finished writing the book (or any of his three novels, for that matter), and Harman makes no attempt to reconcile the plot, opting instead to simply reproduce (in frank English, of course) the words Kafka wrote.

Amerika is not the starting place for those new to Kafka’s work–I would suggest readers who weren’t turned off by their high school English teacher’s inept bungling of The Metamorphosis start with a collection of the short stories. However, I think Harman’s translation is not only essential for fans who wish to rediscover an old favorite, I also believe that it will quickly become the definitive translation. It’s modern and terse and funny, and it also pays subtle respect to the dialogic interplay between Karl’s point of view and that of the omniscient narrator, often creating moments of intense and delicious irony. Reading a translation of Kafka focusing on his oft-neglected humor brought to mind the late great David Foster Wallace’s essay, “A Series of Remarks on the Funniness of Kafka, from Which Not Enough Has Been Removed” (read it here or get the mp3 of DFW reading it here). Here is Wallace, explaining why American undergrads don’t get Kafka’s humor:

And it is this, I think, that makes Kafka’s wit inaccessible to children whom our culture has trained to see jokes as entertainment and entertainment as reassurance. It’s not that students don’t “get” Kafka’s humor but that we’ve taught them to see humor as something you get — the same way we’ve taught them that a self is something you just have. No wonder they cannot appreciate the really central Kafka joke — that the horrific struggle to establish a human self results in a self whose humanity is inseparable from that horrific struggle. That our endless and impossible journey toward home is in fact our home.

Wallace’s observation stealthily acknowledges why the heroes of Amerika and The Trial and The Castle never get to where they’re going, why Kafka could never wrap up his big stories. Kafka, the first modern writer, embraced the “horrific struggle” of humanity and never sought easy reconciliation or pat conclusions. Harman’s new translation brings this critical aspect of Kafka’s writing to the fore, and he achieves this in the most simplistic manner: unobtrusively letting Kafka’s words stand on their own. Recommended.

Amerika is now available from Schocken Books.