Mahendra Singh’s new book is a graphic-novelization of Lewis Carroll’s epic poem The Hunting of the Snark (read our review). Singh was kind enough to talk to us about his project over a series of emails. The Hunting of the Snark is available now in hardback from Melville House. You can read more about Singh’s work at his website.

Biblioklept: Where did your interest in Carroll originate?

Biblioklept: Where did your interest in Carroll originate?

Singh: I read the Alice books as a child and only read the Snark when I was a teenager. The Alice’s were fun, as was the Snark, but it also puzzled me at first. It was hard-core Nonsense and it took me a while to digest it, and half-way understand it. It was a great mental stretching exercise, still is. Kids need that sort of thing if they want their brains to grow up to be something besides consumer units.

Alice’s game of Nonsense is really a warm-up to the Snark’s. When Carroll got to the Snark, he’d had a bit of practice and was in top form. The Snark is really Alice 2.0, the more expensive professional upgrade to Nonsense Making.

When I was young, I had odd reading tastes. From 70s SF to Aristophanes to the Ramayana; I was a little piggy. What I usually liked was a complex, completely furnished fictional world, along with a nice musicality with words. What really turned me on was when that fictional world would be logically intertwined with the real world, past or present. In short, one world would be a sort of code for the other.

I think a lot of kids still like that, it’s really the basic premise of most storytelling, although nowadays it is often so deeply monetized and predigested that it’s hard to really enjoy or even benefit from.

In any case, everything Carroll wrote fit my tastes, but the Snark was extra-special, the difference being that this epic poem (the only genuine Victorian epic poem and I’ll defend that claim against all comers), this epic took the Alice premise of mismatching appearances and meaning and took it to its logical conclusion, which itself is another Nonsense paradox doubled upon itself — beware these Carrollian infinite regressions!

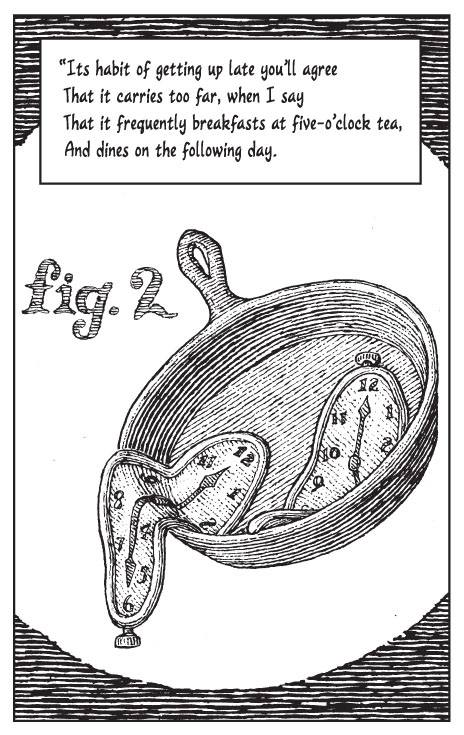

In the Snark, the story-telling code of Nonsense is perfected. Most of the elements are still drawn from the familiar, real world but they are so recombined that their appearances and meaning are impossible to decipher anymore. And yet the persistent, nagging feeling of a genuine logic behind it all still remains.

I think for most young people who are thinking things over, the above Snarkian description is a pretty accurate of their budding world view. And anyway, breaking world-codes was pure catnip for me, it’s the essence of reading, good reading anyway.

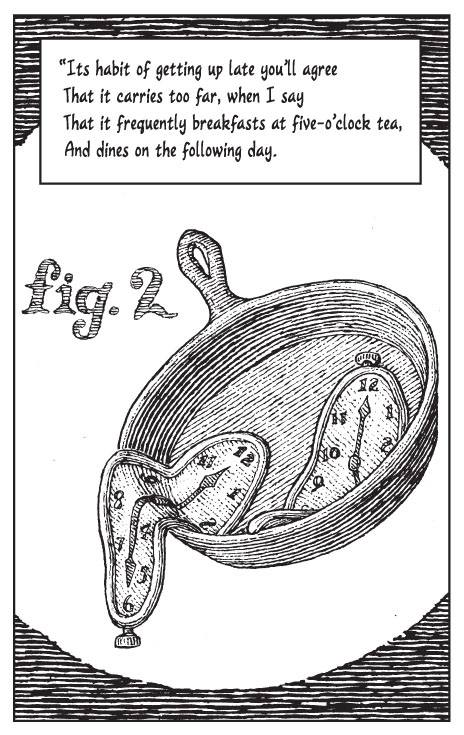

And I have to mention the poetry. I’ve always loved poetry and Carroll’s verse skills in the Snark are the perfect vehicle for what he’s doing. Their anapestic bounce, their goofy mouth feel (the mouthfeel of Old English poetry charms and chants) make a perfect vehicle for the code. It’s a bit of a music hall, Gilbert & Sullivan feel to what is technically a tragic verse epic.

I wouldn’t say I’m a full-bore Carrollian Obsessive, I’ve met plenty of them and they’re dangerous … quiet, nattily dressed librarians with bow ties and a deadpan penchant for puns and parody. Book editors concealing rural silos crammed full of highly addictive Carrollian Nonsense. Carrollian Illuminatis cleverly disguised as entomologists hanging out at obscure Snarkian forestry associations.

I’m just a Carrollian Nutter, I’m harmless as long as I have access to drawing materials. And pictures of Snarks.

Biblioklept: You’ve described your work on Snark as “fitting Lewis Carroll into a protosurrealist straitjacket with matching Dada cufflinks.” Why do the techniques of surrealism and Dada lend themselves to Carroll?

Biblioklept: You’ve described your work on Snark as “fitting Lewis Carroll into a protosurrealist straitjacket with matching Dada cufflinks.” Why do the techniques of surrealism and Dada lend themselves to Carroll?

Singh: Surrealism is one of those things that everyone can point at but few can define. It’s the idea of awakening the sleeper within us and letting them speak to us in their own dream language of pictures and words. Since dreams are a universal form of memory that draw upon every possible human experience, Surrealism is sort of the simultaneous dream-memory of everything.

Protosurrealism is what I call the comfy, cozy Carrollian straitjacket I’ve trapped my Snark in. Carroll was himself hailed as a protosurrealist by the founding fathers of this odd cult, Breton, Aragon, etc. His work, with its dreamlike logic and free associations entranced them and they regarded him as a unique trail-blazer in their explorations. And his verse, to me, is the epitome of the dream world; all poetry (Nonsense or otherwise) must surely be the natural, Adamic language of dreams!

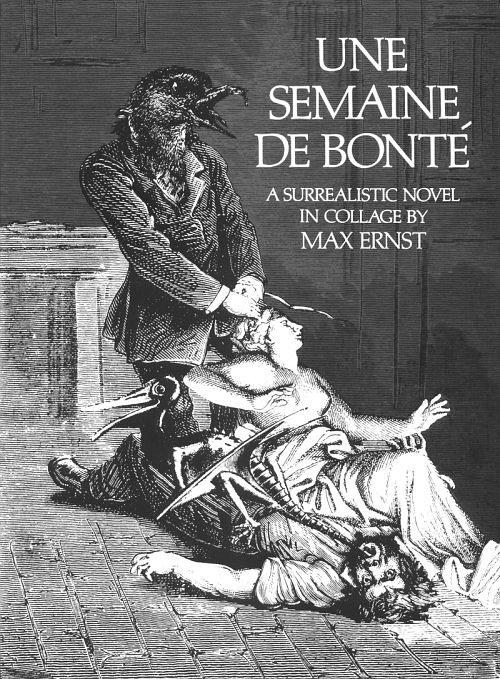

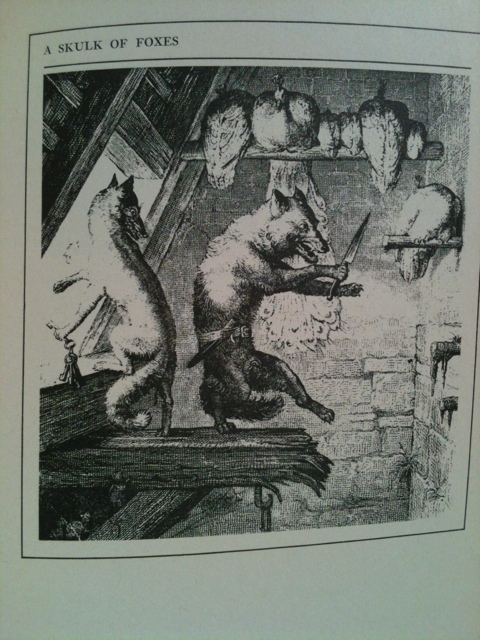

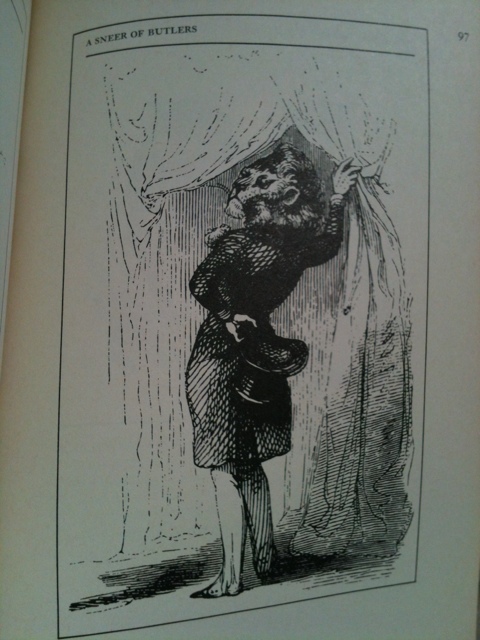

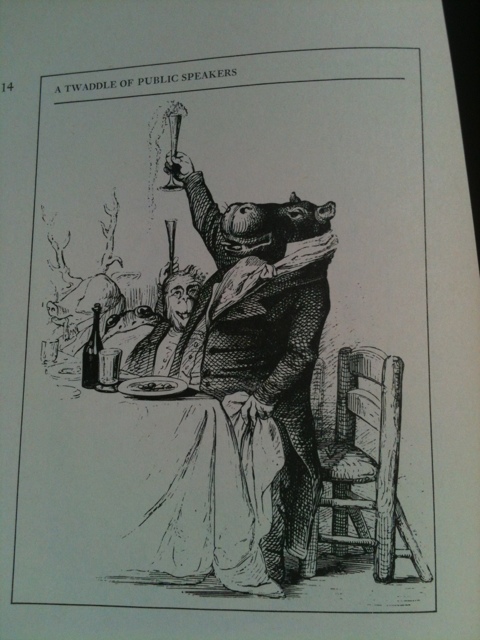

The Surrealist Max Ernst was an enormous inspiration to me — his technique of using 19th-century engravings to illustrate dream stories is brilliant; the old-fashioned, realistic visual style gives them a jarring sense of authority. Realism is the optimal style of the determined dreamer! The urban dreamscapes and dream-eroded objects of Giorgio de Chirico and his brother, the unjustly neglected Alberto Savinio, were also part of my bag of tricks. And of course, references to Rene Magritte are scattered everywhere in this Snark. Magritte’s various techniques for undermining systems of linguistic and visual meaning are ideally suited to navigating the Carrollian Multiverse.

It’s hard to illustrate an idea and oddly enough, the Snark is really a poem of ideas, couched in the form of a tragic epic and then declaimed by a master comedian. One thing I wanted to avoid was doing literal drawings of the scenes in it; I wanted the Snark to constantly bring up a stream of associations, references, insinuations, all of them triggering more and faster allusions, what I call a gateway Surrealism that leaves readers hopelessly addicted and desperate for more! Don’t say no, kids!

It’s hard to illustrate an idea and oddly enough, the Snark is really a poem of ideas, couched in the form of a tragic epic and then declaimed by a master comedian. One thing I wanted to avoid was doing literal drawings of the scenes in it; I wanted the Snark to constantly bring up a stream of associations, references, insinuations, all of them triggering more and faster allusions, what I call a gateway Surrealism that leaves readers hopelessly addicted and desperate for more! Don’t say no, kids!

I’ll add that protosurrealism is the 21st-century application of 19th-century answers to 20th-century problems. The application is this 21st century Snark, the answers are the Victorian rendering style I used and also Carroll’s entire invention of Victorian Nonsense, and the questions are the existential questions that 20th-century artists couched in the language of Surrealism.

Plus, let’s face it, Surrealism just looks cooler! Who wants a postmodernist or abstract expressionist Snark? And the smart kids love it, they’re still young enough to dare to question the sordid, official version of reality. Which is where Dada comes in — there’s a bit of it in my Snark and it’s there because Dada was the ultimate poke in Western Civ’s eye. If the idea of using a blank map isn’t pure Dada, what is it then?

It’s odd having to discuss this in words, proof positive that the Surrealist project remains unfinished. In a perfect Surrealist world, the meaning of my Snark would bleed out of the book and contaminate the reader’s world until they could not distinguish where the Snark began or reality left off. And that’s the essence of Carrollian Nonsense, fiddling with the logical doors of perception.

Biblioklept: Much of surrealist and Dadaist art seems to be an immediate response to mechanical reproduction. In Snark, you seem to at times be reconfiguring, recombining, recontextualizing otherwise familiar images. How do you work? How do you go about creating your art? Can you describe your process?

Singh: Mechanical reproduction can be a loaded phrase. Walter Benjamin gave it quite the kick in the pants, pointing out that it is a degradation of the cult object, a commodification, etc. But the problem is us, the public. A work of art has absolutely no meaning or value except what the viewer puts into it. This is a very important point. If art is degraded or degrades others, it is our choice.

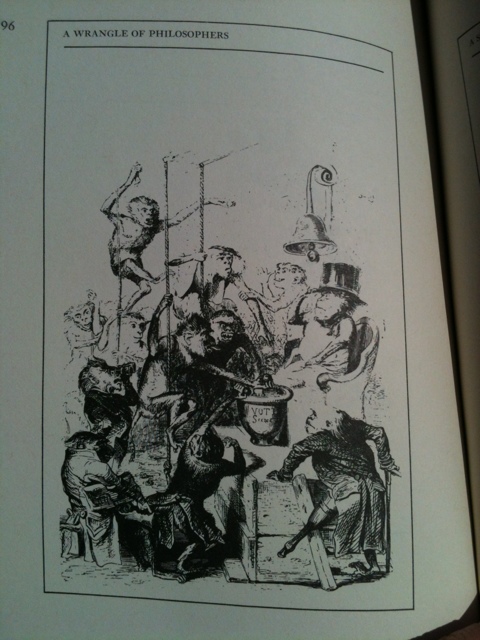

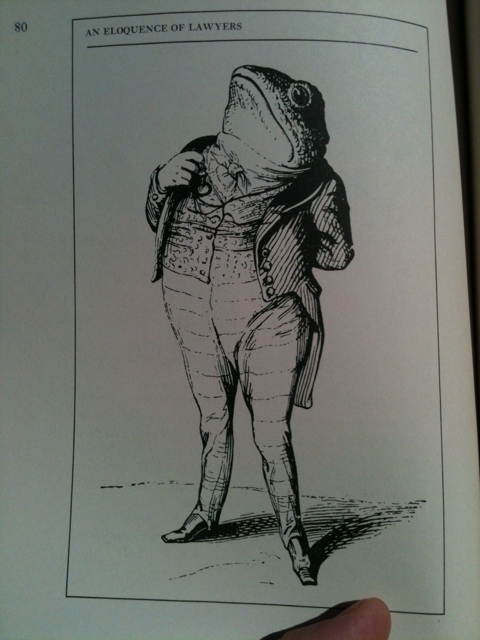

Poor Benjamin, a smart guy but always wriggling back into a Marxist strait-jacket just as useless as medieval Scholasticism or modern neoconservatism. At least Carrollian Nonsense makes the kiddies giggle! He never grasped that all philosophy is individual psychology (and wish-fulfilment) in essence. That’s why the Banker in my Snark is Karl Marx — revenge was sweet! I also included Nietzsche as the Bonnet-maker and Heidegger as the Barrister to round things off. I can assure you, several philosophers were injured in the course of this production. A broken ontology can be quite painful.

Poor Benjamin, a smart guy but always wriggling back into a Marxist strait-jacket just as useless as medieval Scholasticism or modern neoconservatism. At least Carrollian Nonsense makes the kiddies giggle! He never grasped that all philosophy is individual psychology (and wish-fulfilment) in essence. That’s why the Banker in my Snark is Karl Marx — revenge was sweet! I also included Nietzsche as the Bonnet-maker and Heidegger as the Barrister to round things off. I can assure you, several philosophers were injured in the course of this production. A broken ontology can be quite painful.

Nothing has meaning or value unless we decide it does. For years, readers have puzzled over the meaning behind the Snark. It’s another Carrolian Zen koan : the meaning is the meaning. It’s always been staring us in the face, the meaning of the Snark is a verb, it is to search for meaning and when doing so, one automatically generates a meaniningful purpose just as naturally as a spider ejects its web. Inside this silky web is the comfort of whatever logic you feel up to (and that is the secret pleasure of Carrollian Nonsense) and outside the web is just chaos, a Boojum!

In my Snark I’ve mashed up artists including Hieronymous Bosch, Grünewald, Titian, Théodore Géricault, David, Ingres, even George Herriman and also many Surrealists such as Man Ray, Dali, Magritte, etc. There are musicians and authors, the Beatles and Gilbert and Sullivan, Edgar Allan Poe, the Comte de Lautremont, even Victorian parlor games and optical illusions. The idea was to create a web, a labyrinth of allusions in which to hunt the Snark. Some of the references will be familiar but some will not and the reader, if so inclined, can hunt them down on their own. It’s a hunt within a hunt, another Carrollian regression.

The educational aspect is important to me. I really do hope some of the kids who read this will get curious and start off on their own, pillaging a library, ransacking a museum, sneaking into the opera, whatever turns them on. The smart kids are hungry for culture. We must get them thinking, to get them to manufacture and own their own meanings before a mass-marketing goon does it for them.

The actual process of creating the imagery was simple, it’s basically me lying on a sofa, maybe a quick snooze and then free-associating while pondering the text. The cover image is a good example, it’s also the illustration for the whiskered Snarks who scratch and the feathered Snarks who bite. This made me think of Old Scratch, the devil, AKA Lucifer, who was once an angel with feathered wings who also showed a nasty tendency to bite the hand that feeds. I had a vague visual memory of seeing a photo of a surrealist devil; I rummaged through some books until I found it — Denise Bellon’s photo of the Québécois Surrealist, Jean Benoit, at a costume party.

The actual process of creating the imagery was simple, it’s basically me lying on a sofa, maybe a quick snooze and then free-associating while pondering the text. The cover image is a good example, it’s also the illustration for the whiskered Snarks who scratch and the feathered Snarks who bite. This made me think of Old Scratch, the devil, AKA Lucifer, who was once an angel with feathered wings who also showed a nasty tendency to bite the hand that feeds. I had a vague visual memory of seeing a photo of a surrealist devil; I rummaged through some books until I found it — Denise Bellon’s photo of the Québécois Surrealist, Jean Benoit, at a costume party.

The slippers are what caught my eye, it made me think of Old Scratch lounging at home in Pandemonium, his day off, not bothering to shave, hence the whiskers that scratch. I made the toes unequal on a lark, it just seemed right to have Satan misshapen but afterwards I came up with a cabalistic explanation which I won’t bore you with for now.

I then did a pencil drawing on tissue paper, constantly refining and adding or deleting, this was the slowest part of the entire Snark, the pencils. Afterwards I did the pen and ink drawing atop the tissue, on Denril, a synthetic vellum. This is an old technical illustrator’s work habit, which is how I started out actually, in the 80s.

This business of free associating while simultaneously referring to one’s internal visual memory is only possible if one has spent many years romping though books and museums. You cannot be a serious illustrator if you don’t read and look voraciously, all the time. And above all, don’t look at too much rubbish or you will start drawing rubbish. Art students reading this, take heed! You are what you see.

Recombining Surrealism and other –isms, along with the free associations triggered by Carroll’s Nonsense verse, creates a matrix which allows the reader to move seamlessly back and forth between the worlds of dreams, culture, memory and emotion. Those readers who catch the references will enjoy the historical and even non-verbal logic binding them, the rest is up to you.

You are really bringing the meaning with you, and when confronted by my Snark I hope it triggers a cascade of free associations, a mental phenomenon which is the precursor to dreaming, the royal road of Surrealism and Carrollian Nonsense.

Singh: Holiday’s illustrations are odd things, I’ve never been very keen on them. He was a graceful artist usually, very talented and yet these drawings are a bit grotesque, ugly perhaps. They just don’t look so appealing to me. The technique is flawless though, a very classic British style of line work that lasted well into the 1940s.

Some Snarkologists believe that Holiday worked with Carroll to hide a secret meaning in the art. Angles and distances have been measured, objects analysed, hidden shapes discovered and reconfigured. Who knows? It’s unlikely but in any case, you can’t avoid Holiday if you’re doing the Snark.

I used some of his symbols, the bare-breasted woman and her anchor representing Hope, a very british motif which suits the nautical nature of much of the quest. His picture of the Beaver doing its math problem inspired me to treat that entire Fit the Fifth as a long variation upon the Temptation of St. Anthony, especially the version by Bosch. Holiday really nailed that one. I have to confess that Flaubert’s version is a favorite book of mine and I tried to give this part of the Snark the same baroque, over the top feeling of deranged pagan vs. Christian imagery.

Holiday also crammed a considerable number of small details in the Beaver illustration. It’s quite a contrast to the style of the other big Carroll illustrator, Sir John Tenniel, who favored a cleaner look. Nowadays this technique is called “chicken fat” and I used a lot of chicken fat in my Snark, more than Holiday. Of course, with only 9 drawings, he had to keep to a slower visual tempo. That was another reason I did it as a graphic novel — I could vary the tempo quite a bit and really overwhelm the reader with chicken fat when the verses demanded it.

On the other hand, doing it as a graphic novel required creating a narrative visual thread through the whole thing, something which Holiday really didn’t need. In this case, my idea was to make it a theatrical presentation, each Fit a new set change until the end, when Carroll is revealed as the spectator in the empty hall. Carroll was fond of theatricals and the Snark does have a stagey feel to it anyway.

Biblioklept: Have you ever stolen a book?

Singh: Yes, Aces High, a lavishly illustrated book about British fighter pilot aces of WWI. It once graced the shelves of the high school I once attended in a desultory manner (myself, not the book). I was, and still am, fascinated by all things aviation and I could not bear the sight of that wonderful book languishing there, unremarked, unappreciated. I still know the difference between a Sopwith Pup and a Sopwith Camel and I love a well-executed Immelman at the crack of dawn. It was wrong to do and I can only plead callow youth in my defence. Don’t do it, kids! It isn’t worth it! Gosh, I hope Mrs. Merrill isn’t reading this . . .

Biblioklept: Where did your interest in Carroll originate?

Biblioklept: Where did your interest in Carroll originate? Biblioklept: You’ve described your work on Snark as “fitting Lewis Carroll into a protosurrealist straitjacket with matching Dada cufflinks.” Why do the techniques of surrealism and Dada lend themselves to Carroll?

Biblioklept: You’ve described your work on Snark as “fitting Lewis Carroll into a protosurrealist straitjacket with matching Dada cufflinks.” Why do the techniques of surrealism and Dada lend themselves to Carroll? It’s hard to illustrate an idea and oddly enough, the Snark is really a poem of ideas, couched in the form of a tragic epic and then declaimed by a master comedian. One thing I wanted to avoid was doing literal drawings of the scenes in it; I wanted the Snark to constantly bring up a stream of associations, references, insinuations, all of them triggering more and faster allusions, what I call a gateway Surrealism that leaves readers hopelessly addicted and desperate for more! Don’t say no, kids!

It’s hard to illustrate an idea and oddly enough, the Snark is really a poem of ideas, couched in the form of a tragic epic and then declaimed by a master comedian. One thing I wanted to avoid was doing literal drawings of the scenes in it; I wanted the Snark to constantly bring up a stream of associations, references, insinuations, all of them triggering more and faster allusions, what I call a gateway Surrealism that leaves readers hopelessly addicted and desperate for more! Don’t say no, kids! Poor Benjamin, a smart guy but always wriggling back into a Marxist strait-jacket just as useless as medieval Scholasticism or modern neoconservatism. At least Carrollian Nonsense makes the kiddies giggle! He never grasped that all philosophy is individual psychology (and wish-fulfilment) in essence. That’s why the Banker in my Snark is Karl Marx — revenge was sweet! I also included Nietzsche as the Bonnet-maker and Heidegger as the Barrister to round things off. I can assure you, several philosophers were injured in the course of this production. A broken ontology can be quite painful.

Poor Benjamin, a smart guy but always wriggling back into a Marxist strait-jacket just as useless as medieval Scholasticism or modern neoconservatism. At least Carrollian Nonsense makes the kiddies giggle! He never grasped that all philosophy is individual psychology (and wish-fulfilment) in essence. That’s why the Banker in my Snark is Karl Marx — revenge was sweet! I also included Nietzsche as the Bonnet-maker and Heidegger as the Barrister to round things off. I can assure you, several philosophers were injured in the course of this production. A broken ontology can be quite painful.

More info

More info