The Fire-writing, 1953 by J.R.R. Tolkien (1892–1973).

From The Morgan Library & Museum’s exhibition “Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth.”

The Fire-writing, 1953 by J.R.R. Tolkien (1892–1973).

From The Morgan Library & Museum’s exhibition “Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth.”

The Tree of Tongues, c. 1930-37 by J.R.R. Tolkien (1892–1973).

From The Morgan Library & Museum’s exhibition “Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth.”

The science magazine Nautilus has published Cormac McCarthy’s essay “The Kekulé Problem.” This is the first piece of nonfiction that McCarthy has published. It’s a fascinating essay that takes its name from a dream of Friedrich August Kekulé, “father of organic chemistry.” Kekulé dreamed of an ouroboros, an unconscious insight that led him to “discover” the ring-structure of the benzene molecule. (Thomas Pynchon writes about Kekulé’s dream in Gravity’s Rainbow, by the way). Anyway, it’s a nice piece on a complex subject, and it’s fun to watch McCarthy move from lucid, transparent, and direct prose into wry fragments that are, well, more McCarthyesque. From the essay––

The evolution of language would begin with the names of things. After that would come descriptions of these things and descriptions of what they do. The growth of languages into their present shape and form—their syntax and grammar—has a universality that suggests a common rule. The rule is that languages have followed their own requirements. The rule is that they are charged with describing the world. There is nothing else to describe.

All very quickly. There are no languages whose form is in a state of development. And their forms are all basically the same.

We dont know what the unconscious is or where it is or how it got there—wherever there might be. Recent animal brain studies showing outsized cerebellums in some pretty smart species are suggestive. That facts about the world are in themselves capable of shaping the brain is slowly becoming accepted. Does the unconscious only get these facts from us, or does it have the same access to our sensorium that we have? You can do whatever you like with the us and the our and the we. I did. At some point the mind must grammaticize facts and convert them to narratives. The facts of the world do not for the most part come in narrative form. We have to do that.

The Hobbit Is a Picaresque Novel

“I Have a Very Vivid Child’s View” — A 1967 Interview with J.R.R. Tolkien

J.R.R. Tolkien, In His Own Words (1968 BBC Documentary)

There are in English often long trains of words allied by their meaning and derivation; as, to beat, a bat, batoon, a battle, a beetle, a battledore, to batter, batter, a kind of glutinous composition for food, made by beating different bodies into one mass. All these are of similar signification, and perhaps derived from the Latin batuo. Thus take, touch, tickle, tack, tackle; all imply a local conjunction from the Latin tango, tetigi, tactum.

From two are formed twain, twice, twenty, twelve, twins, twine, twist, twirl, twig, twitch, twinge, between, betwixt, twilight, twibil.

The following remarks, extracted from Wallis, are ingenious but of more subtlety than solidity, and such as perhaps might in every language be enlarged without end.

Sn usually imply the nose, and what relates to it. From the Latin nasus are derived the French nez and the English nose; and nesse, a promontory, as projecting like a nose. But as if from the consonants ns taken from nasus, and transposed that they may the better correspond, sn denote nasus; and thence are derived many words that relate to the nose, as snout, sneeze, snore, snort,snear, snicker, snot, snivel, snite, snuff, snuffle, snaffle, snarl, snudge.

There is another sn which may perhaps be derived from the Latin sinuo, as snake, sneak, snail, snare; so likewise snap and snatch, snib, snub. Bl imply a blast; as blow, blast, to blast, to blight, and, metaphorically, to blast one’s reputation;bleat, bleak, a bleak place, to look bleak, or weather-beaten, black, blay, bleach, bluster, blurt, blister, blab, bladder, blew, blabber lip’t, blubber-cheek’t, bloted, blote-herrings, blast, blaze, to blow, that is, blossom, bloom; and perhapsblood and blush.

In the native words of our tongue is to be found a great agreement between the letters and the thing signified; and therefore the sounds of the letters smaller, sharper, louder, closer, softer, stronger, clearer, more obscure, and more stridulous, do very often intimate the like effects in the things signified.

Thus words that begin with str intimate the force and effect of the thing signified, as if probably derived from στρωννυμι, or strenuous; as strong, strength, strew, strike, streak, stroke, stripe, strive, strife, struggle, strout, strut, stretch, strait,strict, streight, that is, narrow, distrain, stress, distress, string, strap, stream, streamer, strand, strip, stray, struggle, strange, stride, stradale.

St in like manner imply strength, but in a less degree, so much only as is sufficient to preserve what has been already communicated, rather than acquire any new degree; as if it were derived from the Latin sto; for example, stand, stay, that is, to remain, or to prop; staff, stay, that is, to oppose; stop, to stuff, stifle, to stay, that is, to stop; a stay, that is, an obstacle; stick, stut, stutter, stammer, stagger, stickle, stick, stake, a sharp, pale, and any thing deposited at play; stock, stem,sting, to sting, stink, stitch, stud, stuncheon, stub, stubble, to stub up, stump, whence stumble, stalk, to stalk, step, to stamp with the feet, whence to stamp, that is, to make an impression and a stamp; stow, to stow, to bestow, steward, orstoward; stead, steady, stedfast, stable, a stable, a stall, to stall, stool, stall, still, stall, stallage, stage, still, adjective, and still, adverb: stale, stout, sturdy, stead, stoat, stallion, stiff, stark-dead, to starve with hunger or cold; stone, steel,stern, stanch, to stanch blood, to stare, steep, steeple, stair, standard, a stated measure, stately. In all these, and perhaps some others, st denote something firm and fixed.

Thr imply a more violent degree of motion, as throw, thrust, throng, throb, through, threat, threaten, thrall, throws.

Wr imply some sort of obliquity or distortion, as wry, to wreathe, wrest, wrestle, wring, wrong, wrinch, wrench, wrangle, wrinkle, wrath, wreak, wrack, wretch, wrist, wrap.

Sw imply a silent agitation, or a softer kind of lateral motion; as sway, swag, to sway, swagger, swerve, sweat, sweep, swill, swim, swing, swift, sweet, switch, swinge.

Nor is there much difference of sm in smooth, smug, smile, smirk, smite; which signifies the same as to strike, but is a softer word; small, smell, smack, smother, smart, a smart blow properly signifies such a kind of stroke as with an originally silent motion, implied in sm, proceeds to a quick violence, denoted by ar suddenly ended, as is shown by t.

Cl denote a kind of adhesion or tenacity, as in cleave, clay, cling, climb, clamber, clammy, clasp, to clasp, to clip, to clinch, cloak, clog, close, to close, a clod, a clot, as a clot of blood, clouted cream, a clutter, a cluster.

Sp imply a kind of dissipation or expansion, especially a quick one, particularly if there be an r, as if it were from spargo or separo: for example, spread, spring, sprig, sprout, sprinkle, split, splinter, spill, spit, sputter, spatter.

Sl denote a kind of silent fall, or a less observable motion; as in slime, slide, slip, slipper, sly, sleight, slit, slow, slack, slight, sling, slap.

And so likewise ash, in crash, rash, gash, flash, clash, lash, slash, plash, trash, indicate something acting more nimbly and sharply. But ush, in crush, rush, gush, flush, blush, brush, hush, push, imply something as acting more obtusely and dully. Yet in both there is indicated a swift and sudden motion not instantaneous, but gradual, by the continued sound, sh.

Thus in fling, sling, ding, swing, cling, sing, wring, sting, the tingling of the termination ng, and the sharpness of the vowel i, imply the continuation of a very slender motion or tremor, at length indeed vanishing, but not suddenly interrupted. [31]But in tink, wink, sink, clink, chink, think, that end in a mute consonant, there is also indicated a sudden ending.

If there be an l, as in jingle, tingle, tinkle, mingle, sprinkle, twinkle, there is implied a frequency, or iteration of small acts. And the same frequency of acts, but less subtile by reason of the clearer vowel a, is indicated in jangle, tangle,spangle, mangle, wrangle, brangle, dangle; as also in mumble, grumble, jumble. But at the same time the close u implies something obscure or obtunded; and a congeries of consonants mbl, denotes a confused kind of rolling or tumbling, as in ramble, scamble, scramble, wamble, amble; but in these there is something acute.

In nimble, the acuteness of the vowel denotes celerity. In sparkle, sp denotes dissipation, ar an acute crackling, k a sudden interruption, l a frequent iteration; and in like manner in sprinkle, unless in may imply the subtilty of the dissipated guttules. Thick and thin differ in that the former ends with an obtuse consonant, and the latter with an acute.

In like manner, in squeek, squeak, squeal, squall, brawl, wraul, yaul, spaul, screek, shriek, shrill, sharp, shrivel, wrinkle, crack, crash, clash, gnash, plash, crush, hush, hisse, fisse, whist, soft, jar, hurl, curl, whirl, buz, bustle, spindle, dwindle, twine, twist, and in many more, we may observe the agreement of such sort of sounds with the things signified; and this so frequently happens, that scarce any language which I know can be compared with ours. So that one monosyllable word, of which kind are almost all ours, emphatically expresses what in other languages can scarce be explained but by compounds, or decompounds, or sometimes a tedious circumlocution.

(From Samuel Johnson’s A Grammar of the English Tongue).

Books acquired, 2.28.2012. All forthcoming from Pantheon, all hardback:

The Undead by Dick Teresi is a book about organ harvesting that claims to be funny. Publisher’s description:

Important and provocative, The Undead examines why even with the tools of advanced technology, what we think of as life and death, consciousness and nonconsciousness, is not exactly clear and how this problem has been further complicated by the business of organ harvesting.

Dick Teresi, a science writer with a dark sense of humor, manages to make this story entertaining, informative, and accessible as he shows how death determination has become more complicated than ever. Teresi introduces us to brain-death experts, hospice workers, undertakers, coma specialists and those who have recovered from coma, organ transplant surgeons and organ procurers, anesthesiologists who study pain in legally dead patients, doctors who have saved living patients from organ harvests, nurses who care for beating-heart cadavers, ICU doctors who feel subtly pressured to declare patients dead rather than save them, and many others. Much of what they have to say is shocking. Teresi also provides a brief history of how death has been determined from the times of the ancient Egyptians and the Incas through the twenty-first century. And he draws on the writings and theories of celebrated scientists, doctors, and researchers—Jacques-Bénigne Winslow, Sherwin Nuland, Harvey Cushing, and Lynn Margulis, among others—to reveal how theories about dying and death have changed. With The Undead, Teresi makes us think twice about how the medical community decides when someone is dead.

Jonathan Haidt’s The Righteous Mind. Publisher’s description:

Why can’t our political leaders work together as threats loom and problems mount? Why do people so readily assume the worst about the motives of their fellow citizens? In The Righteous Mind, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt explores the origins of our divisions and points the way forward to mutual understanding.

His starting point is moral intuition—the nearly instantaneous perceptions we all have about other people and the things they do. These intuitions feel like self-evident truths, making us righteously certain that those who see things differently are wrong. Haidt shows us how these intuitions differ across cultures, including the cultures of the political left and right. He blends his own research findings with those of anthropologists, historians, and other psychologists to draw a map of the moral domain, and he explains why conservatives can navigate that map more skillfully than can liberals. He then examines the origins of morality, overturning the view that evolution made us fundamentally selfish creatures. But rather than arguing that we are innately altruistic, he makes a more subtle claim—that we are fundamentally groupish. It is our groupishness, he explains, that leads to our greatest joys, our religious divisions, and our political affiliations. In a stunning final chapter on ideology and civility, Haidt shows what each side is right about, and why we need the insights of liberals, conservatives, and libertarians to flourish as a nation.

Daniel L. Everett’s Language: The Cultural Tool caught my fancy the most in this group; I spent two glasses of wine with it and may report more in the future. Publisher’s ‘script after the pic:

A bold and provocative study that presents language not as an innate component of the brain—as most linguists do—but as an essential tool unique to each culture worldwide.

For years, the prevailing opinion among academics has been that language is embedded in our genes, existing as an innate and instinctual part of us. But linguist Daniel Everett argues that, like other tools, language was invented by humans and can be reinvented or lost. He shows how the evolution of different language forms—that is, different grammar—reflects how language is influenced by human societies and experiences, and how it expresses their great variety.

For example, the Amazonian Pirahã put words together in ways that violate our long-held under-standing of how language works, and Pirahã grammar expresses complex ideas very differently than English grammar does. Drawing on the Wari’ language of Brazil, Everett explains that speakers of all languages, in constructing their stories, omit things that all members of the culture understand. In addition, Everett discusses how some cultures can get by without words for numbers or counting, without verbs for “to say” or “to give,” illustrating how the very nature of what’s important in a language is culturally determined.

Combining anthropology, primatology, computer science, philosophy, linguistics, psychology, and his own pioneering—and adventurous—research with the Amazonian Pirahã, and using insights from many different languages and cultures, Everett gives us an unprecedented elucidation of this society-defined nature of language. In doing so, he also gives us a new understanding of how we think and who we are.

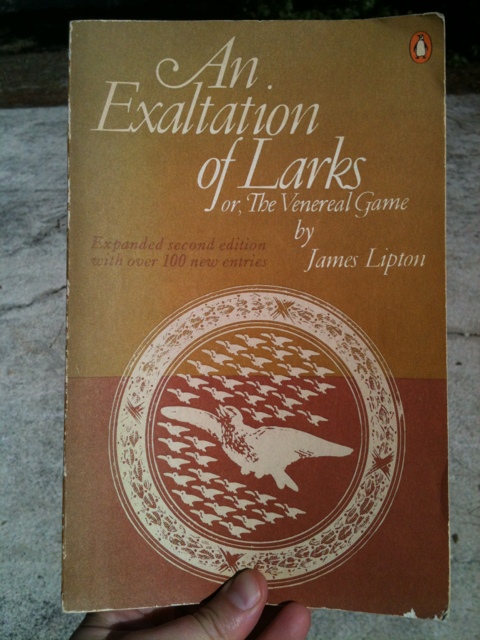

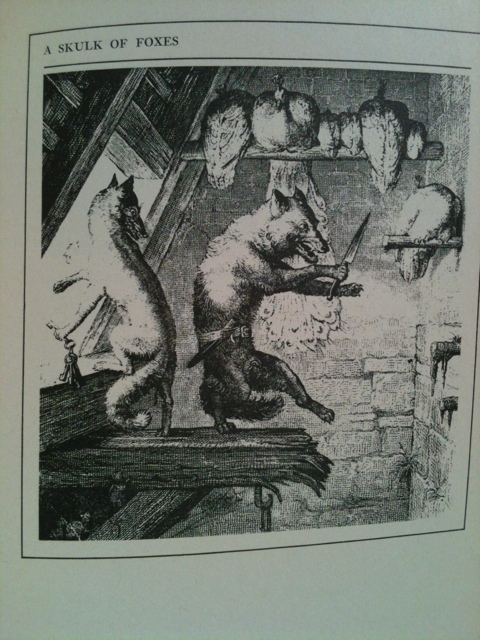

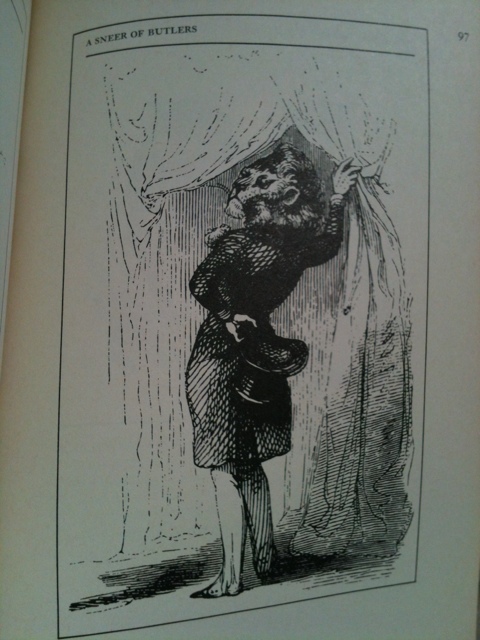

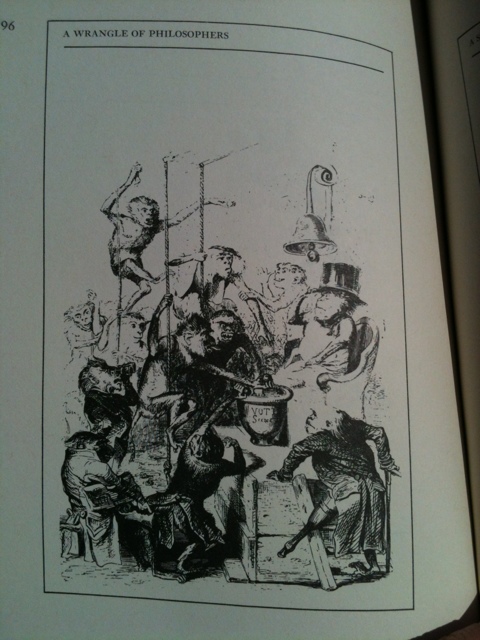

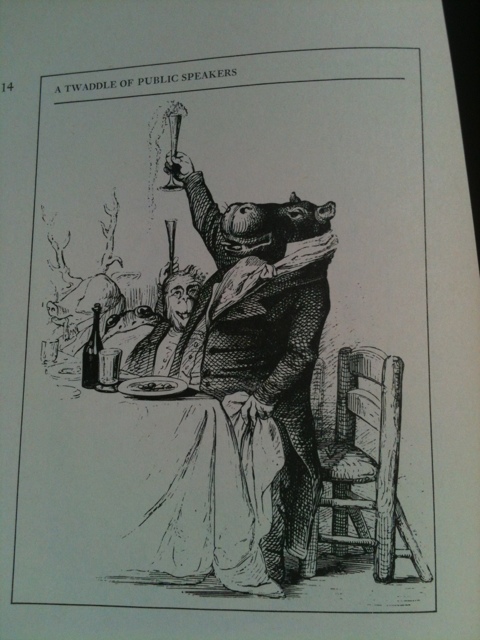

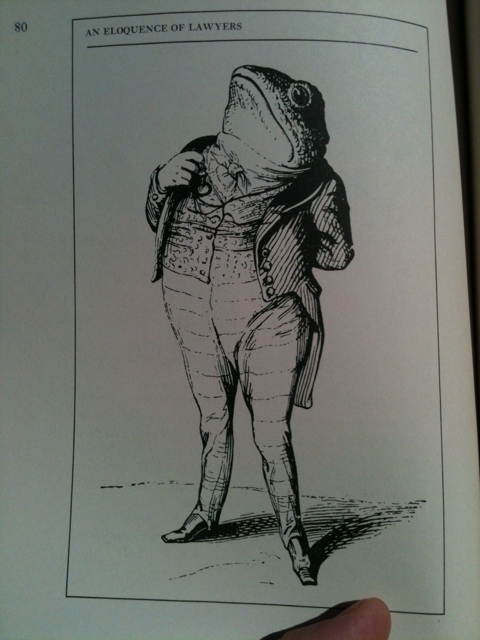

I had never heard of James Lipton’s dictionary of terms of venery, An Exaltation of Larks, or The Venereal Game before I found it wedged between some old etymological dictionaries I was browsing in my favorite book store, but when I picked it up I knew I was going to buy it almost immediately. Part dictionary, part etymology, and part linguistic game, An Exaltation explores those strange collective noncount nouns of English that anglophiles (like me) find so charming and weird. The first part of the book deals with some of the more common terms of venery, like “pride of lions,” or “skulk of foxes”:

But Lipton soon gives over to more esoteric terms, and then eventually plays with outright invention. The book’s illustrations recall Max Ernst’s surrealist graphic novel Une Semaine de Bonté; they also remind me of the recapitations of recent Biblioklept interviewee Click Mort. Anyway, a very cool book, likely a cult favorite, and lots and lots of fun.

Arika Okrent‘s new book In the Land of Invented Languages (released in hard back last month from Spiegel & Grau) confidently traverses the thin line between pop nonfiction and academic linguistics. Subtitled Esperanto Rock Stars, Klingon Poets, Loglan Lovers, and the Mad Dreamers Who Tried to Build a Perfect Language, Okrent’s book delves the weird world of invented languages. While many folks are familiar enough with the idealism behind Esperanto or the sadness behind, ahem, Klingon, what about Lingua Ignota, or Dritok, the chipmunk language? How much do you know about John Wilkins’s 1668 invention “Philosophical Language” (pictured below)?

Okrent, after explaining her fascination with invented languages, or “conlangs,” more or less uses Wilkins as a starting place, using his massive project as a measuring stick for all the invented languages that followed it. While detailing the history and implementation of Esperanto, Charles Bliss’s language of symbols, and the logical logjammin’ of Lojban, Okrent balances the erudition of complex linguistics with a humorous, human tone. In the Land of Invented Languages is filled with tree diagrams and symbol charts that will not be wholly unfamiliar to those who studied a little linguistics back in college (or even those who, like the Biblioklept, changed their major from linguistics to English when they discovered they’d have to take, gasp!, statistics). These visuals are both fun and stimulating, and help to explicate what can be pretty heady stuff at times.

Okrent, after explaining her fascination with invented languages, or “conlangs,” more or less uses Wilkins as a starting place, using his massive project as a measuring stick for all the invented languages that followed it. While detailing the history and implementation of Esperanto, Charles Bliss’s language of symbols, and the logical logjammin’ of Lojban, Okrent balances the erudition of complex linguistics with a humorous, human tone. In the Land of Invented Languages is filled with tree diagrams and symbol charts that will not be wholly unfamiliar to those who studied a little linguistics back in college (or even those who, like the Biblioklept, changed their major from linguistics to English when they discovered they’d have to take, gasp!, statistics). These visuals are both fun and stimulating, and help to explicate what can be pretty heady stuff at times.

At its core, Invented Languages is about dreamers and schemers, the kind of idealistic perfectionists who would go to the trouble to invent something as heavy and impossible as a language. As Okrent savvily points out in her introductory chapter, real languages–that is, the natural languages that people really speak and communicate in–are organic and don’t really require rules. They just “happen.” That’s what makes this book so much fun–all the crazy cranks that try to force their perfect philosophical systems onto the world. In the Land of Invented Languages is a rewarding exploration of meaning and language, how language means, and what happens when we try to make meaning. Recommended.

For more info, check out In the Land of Invented Language‘s fun and thorough website.

It wasn’t so much Governor Palin’s fumbling toward a semblance of specificity in her recent Katie Couric interview that made me cringe. It wasn’t her misapprehension that Putin is still the president of Russia (an honest mistake, I’m sure) that raised my hackles. It wasn’t her neocon-lite reduction of global politics to “good guys” vs “bad guys” that so irritated me. Even her ignorance of Henry Kissinger’s foreign policy philosophy re: Iran didn’t bother me. If anything, I delighted in watching Gov. Palin blather incoherently, especially after this fiasco two weeks ago. No, what really raised the hairs on the back of my neck was this exchange:

Couric: You recently said three times that you would never, quote, “second guess” Israel if that country decided to attack Iran. Why not?

Palin: We shouldn’t second guess Israel’s security efforts because we cannot ever afford to send a message that we would allow a second Holocaust, for one. Israel has got to have the opportunity and the ability to protect itself. They are our closest ally in the Mideast. We need them. They need us. And we shouldn’t second guess their efforts.

But, you see, it wasn’t what she said so much as it was how she said it. Or mispronounced it, rather.

Let me admit it. I’m an elitist, something of a snob I guess. I can’t help it. Although I didn’t go to five colleges, I did attend two universities to earn two degrees–nothing as prestigious as Palin’s hard-earned MS in communications, of course–but I do have some linguistic standards and expectations for our executive leadership. You see, Gov. Palin didn’t say “second guess,” as the CBS News transcript so generously credits her. No, Gov. Palin distinctly says “second guest.”

Now, we already know that Palin has had some difficulty with one of Bush’s biggest stumbling blocks, that oh-so daunting word “nuclear” (as in “nü-klē-ər” not “nyoo-kyoo-lar”). Observe:

Unfortunately, as of right now there’s no full footage of tonight’s interview up on a site that WordPress will allow me to embed here, and most of the posted clips focus on Palin’s rambling knowledge of basic geography (even Miss Teen South Carolina still managed to get more specific than Palin — “They don’t have maps”).

VIDEO UPDATE–Palin mispronounces “second guess” as “second guest” at 00:17:

If you go to CBS News and wait patiently, Palin’s redneck phrasing pops up at 8:55, wedged neatly amid a vague heap of rhetorically empty catchphrases that the neo-cons and Bush administration have been excreting for the past decade.

In the best assessment I’ve read on Palin yet, Roger Ebert points out that most middle-class Americans would brag if their kids went to Harvard on scholarship; that most of us honor travel as a form of education and the signal of intellectual curiosity. How did we get here? When, exactly, did we decide that our president needs to have the qualities of a good drinking buddy? In short, why do we think that provincialism and ignorance, so summarily captured in Palin’s groan-inducing “second guest,” are the signs of a “real,” “true” American? If we’re going to elect smug, hypocritical leaders, is it too much to ask that they exhibit a modicum of intelligence, or, at the very least, don’t trip over their words?