Listening to Gordon Lish read selections from Iambik Audio’s compendium of his Collected Fictions for the fourth time today, it occurred to me that I should just go ahead and review the damn thing. Quit stalling. Get to it. I hope that pointing out that I’ve listened to Lish narrate ten of his odd, funny, gut-wrenching tales four times now (and will surely listen again) is enough to motivate thee, gentle reader, to follow my example—but that’s lazy, wishful thinking, right? There needs to be a proper review. Here goes—

Listening to Gordon Lish read selections from Iambik Audio’s compendium of his Collected Fictions for the fourth time today, it occurred to me that I should just go ahead and review the damn thing. Quit stalling. Get to it. I hope that pointing out that I’ve listened to Lish narrate ten of his odd, funny, gut-wrenching tales four times now (and will surely listen again) is enough to motivate thee, gentle reader, to follow my example—but that’s lazy, wishful thinking, right? There needs to be a proper review. Here goes—

Lish is perhaps more famous as an editor than a writer of short fiction. He worked for years at Vanity Fair and later for Knopf, and the list of writers that he championed reads like a who’s-who of contemporary greats: Don DeLillo, Cynthia Ozick, Amy Hempel, Barry Hannah, David Leavitt, and Harold Brodkey, just to name a few. The writer he is perhaps most associated with though is Raymond Carver. By paring down sentence after sentence, Lish helped Carver develop his spare, minimalist style.

It’s that attention to sentences, to the truth of each sentence, to their individual force, that shines through in the collection. Consider this beauty, from “The Death of Me,” a story about a boy (surely Gordon Lish, hero of all Gordon Lish stories) who peaks too early, winning first place in all five field events at his summer camp one fine day in 1944, and then succumbing to the realization that this apex is, frankly, the end of it all–

I felt like going to sleep and staying asleep until someone came and told me that my parents were dead and that I was all grown up and that there was a new God in heaven and that he liked me better even than the old God had.

This sentence seems to me to be the expression of an emotion that I’ve felt for which I have no name. Lish’s sentences can move through tragedy and pathos to devastating comedy, a kind of comedy that collapses the auditor. Check out a line from “Mr. Goldbaum”–

What if your father was the kind of father who was dying and he called you to him and you were his son and he said for you to come lie down on the bed with him so that he could hold you and so that you could hold him so that you both could be like that hugging with each other like that to say goodbye before you had to actually go leave each other and did it, you did it, you god down on the bed with your father and you got up close to your father and you got your arms around your father and your father was hugging you and you were hugging your father and there was one of you who could not stop it, who could not help it, but who just got a hard-on?

Lish advised, “Don’t have stories — have sentences,” but “The Death of Me” and “Mr. Goldbaum” are more than the sum of their parts, more than just a collection of sculpted, scalpeled syntax. From the 1988 collection Mourner at the Door (the only Lish book I’d read before Collected Fictions), both stories announce Lish’s major theme of death, the absurdity of death, or the absurdity of life against the inevitability of death—but also the heavy truth of death, the ugly truth of death, the powerlessness of language against the finality of death. “Spell Bereavement,” also from Mourner, is essentially a prequel to “Mr. Goldbaum”: Gordon gets the news of his father’s death from his sister and mother. The story takes place over the phone as a sort of switch-hit interrogation, as mom and sis caustically berate the speechless man, who tells us, at the end, “There are not people in my heart of hears. There are just sentences in my heart of hearts.” Why does Gordon the narrator of “Spell Bereavement” fail to respond to the news of his father’s death? He is “too disabled to talk . . . going crazy with pencil and paper so as not to miss one word.”

Lish means to capture the ecstatic truth in death, and truth is at the core of all these stories, even when they are fables of a sort, like “After the Beanstalk,” which features a bewitched princess who has been transmogrified into a dog. The tale is hilarious and cutting and sad. There’s also “Squeak in the Sycamore,” which begins as a child’s list of fears and enumerations of death and longing and nature and ends in a joke and then an insult to the reader for laughing at the joke. (Best line: “Six is: the gardener died from digging up a basilisk”). “How to Write a Poem” is a caustic rant that argues that literary theft is really a matter of stern guts, of facing truth, and “Everything I Know” problematizes the very act of storytelling — it’s a story about how we tell stories, or our versions of stories. By far the most affecting piece that Lish reads though is “Eats with Ozick and Lentricchia,” about which he tells us, before reading it, “there is not a word of it that is not true.” It is a story that hovers around the death, or the dying of, more accurately, Lish’s wife Barbara; its details are almost too cruel, too true to bear.

Lish reads his tales in a bold voice that seems to challenge the auditor at all angles, as if his sentences were prodding you, poking you, pinching you even. He claims, in one of the many asides that precede these tales, to have never really read his work aloud before, and not to have really read the work in years, but his confidence seems to belie this notion; maybe, more accurately, it conveys the intense concentration of his intellect. His tone fascinates, and then he cracks out something like: “It always astonishes me I could have written such a thing” in such a dry honest voice that, while his quip hangs ambiguous, it remains utterly sincere. There’s a wonderful moment in the recording when he moves from reading “Mr. Goldbaum” to “Spell Bereavement” and seems to notice, as if for the first time, their close connection. He then remarks–

It shames me in one kind of way to see that my writing gathers itself into such a rut, but on the other hand it does please me to have spoken again and again and again about that which occurred to me at the time to be of consequence. I haven’t written fiction or anything else really for a great number of years and this occasion, reading these pieces, is an education for me and alien, foreign, in one kind of way, because the sentences are complex, but in another kind of way, I’m reminded of who I am.

Lish’s influence cannot be underestimated, from writers like David Foster Wallace to Denis Johnson to Sam Lipsyte, and all of those who will follow in turn. Readers have a fantastic (and incredibly inexpensive, I must add) starting place in Iambik’s wonderful collection. Do yourself a favor and check this out. Very highly recommended.

Listening to Gordon Lish read selections from

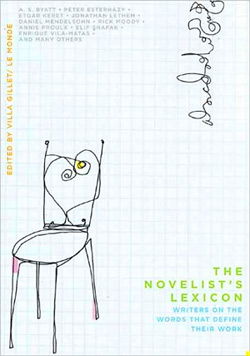

Listening to Gordon Lish read selections from  The Novelist’s Lexicon, new in hardback from

The Novelist’s Lexicon, new in hardback from  Hey. Do yourself a favor and listen to

Hey. Do yourself a favor and listen to