“Emerson” — Charles Ives

from Essays Before a Sonata

It has seemed to the writer, that Emerson is greater—his identity more complete perhaps—in the realms of revelation—natural disclosure—than in those of poetry, philosophy, or prophecy. Though a great poet and prophet, he is greater, possibly, as an invader of the unknown,—America’s deepest explorer of the spiritual immensities,—a seer painting his discoveries in masses and with any color that may lie at hand—cosmic, religious, human, even sensuous; a recorder, freely describing the inevitable struggle in the soul’s uprise—perceiving from this inward source alone, that every “ultimate fact is only the first of a new series”; a discoverer, whose heart knows, with Voltaire, “that man seriously reflects when left alone,” and would then discover, if he can, that “wondrous chain which links the heavens with earth—the world of beings subject to one law.” In his reflections Emerson, unlike Plato, is not afraid to ride Arion’s Dolphin, and to go wherever he is carried—to Parnassus or to “Musketaquid.”

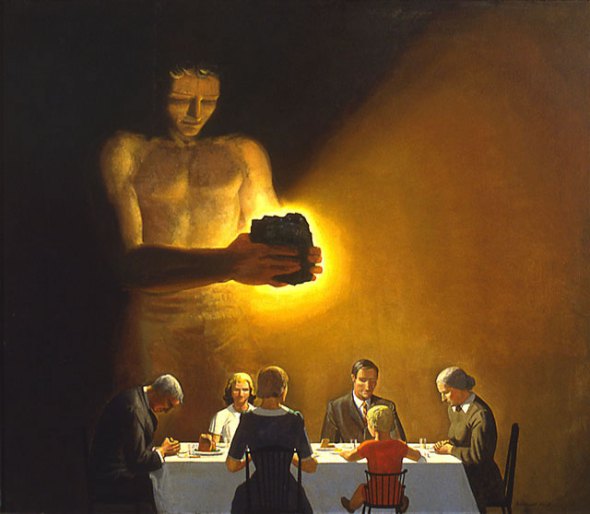

We see him standing on a summit, at the door of the infinite where many men do not care to climb, peering into the mysteries of life, contemplating the eternities, hurling back whatever he discovers there,—now, thunderbolts for us to grasp, if we can, and translate—now placing quietly, even tenderly, in our hands, things that we may see without effort—if we won’t see them, so much the worse for us.

We see him,—a mountain-guide, so intensely on the lookout for the trail of his star, that he has no time to stop and retrace his footprints, which may often seem indistinct to his followers, who find it easier and perhaps safer to keep their eyes on the ground. And there is a chance that this guide could not always retrace his steps if he tried—and why should he!—he is on the road, conscious only that, though his star may not lie within walking distance, he must reach it before his wagon can be hitched to it—a Prometheus illuminating a privilege of the Gods—lighting a fuse that is laid towards men. Emerson reveals the less not by an analysis of itself, but by bringing men towards the greater. He does not try to reveal, personally, but leads, rather, to a field where revelation is a harvest-part, where it is known by the perceptions of the soul towards the absolute law. He leads us towards this law, which is a realization of what experience has suggested and philosophy hoped for. He leads us, conscious that the aspects of truth, as he sees them, may change as often as truth remains constant. Revelation perhaps, is but prophecy intensified—the intensifying of its mason-work as well as its steeple. Simple prophecy, while concerned with the past, reveals but the future, while revelation is concerned with all time. The power in Emerson’s prophecy confuses it with—or at least makes it seem to approach—revelation. It is prophecy with no time element. Emerson tells, as few bards could, of what will happen in the past, for his future is eternity and the past is a part of that. And so like all true prophets, he is always modern, and will grow modern with the years—for his substance is not relative but a measure of eternal truths determined rather by a universalist than by a partialist. He measured, as Michel Angelo said true artists should, “with the eye and not the hand.” But to attribute modernism to his substance, though not to his expression, is an anachronism—and as futile as calling today’s sunset modern.

As revelation and prophecy, in their common acceptance are resolved by man, from the absolute and universal, to the relative and personal, and as Emerson’s tendency is fundamentally the opposite, it is easier, safer and so apparently clearer, to think of him as a poet of natural and revealed philosophy. And as such, a prophet—but not one to be confused with those singing soothsayers, whose pockets are filled, as are the pockets of conservative-reaction and radical demagoguery in pulpit, street-corner, bank and columns, with dogmatic fortune-tellings. Emerson, as a prophet in these lower heights, was a conservative, in that he seldom lost his head, and a radical, in that he seldom cared whether he lost it or not. He was a born radical as are all true conservatives. He was too much “absorbed by the absolute,” too much of the universal to be either—though he could be both at once. To Cotton Mather, he would have been a demagogue, to a real demagogue he would not be understood, as it was with no self interest that he laid his hand on reality. The nearer any subject or an attribute of it, approaches to the perfect truth at its base, the more does qualification become necessary. Radicalism must always qualify itself. Emerson clarifies as he qualifies, by plunging into, rather than “emerging from Carlyle’s soul-confusing labyrinths of speculative radicalism.” The radicalism that we hear much about today, is not Emerson’s kind—but of thinner fiber—it qualifies itself by going to A “root” and often cutting other roots in the process; it is usually impotent as dynamite in its cause and sometimes as harmful to the wholesome progress of all causes; it is qualified by its failure. But the Radicalism of Emerson plunges to all roots, it becomes greater than itself—greater than all its formal or informal doctrines—too advanced and too conservative for any specific result—too catholic for all the churches—for the nearer it is to truth, the farther it is from a truth, and the more it is qualified by its future possibilities. Continue reading ““Emerson” — Charles Ives” →