[Ed. note: The following citations come from one-star Amazon reviews of James Joyce’s Ulysses. To be clear, I think Ulysses is a marvelous, rewarding read. While one or two of the reviews are tongue-in-cheek, most one-star reviews of the book are from very, very angry readers who feel duped]

I can sum this book up in two words: “Ass Beating”.

What an awful book this is?

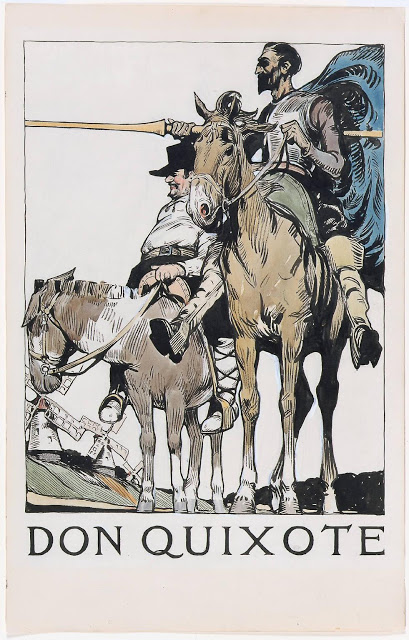

I bought this having been a huge fan of the cartoon series, but Mr Joyce has taken a winning formula and produced a prize turkey. After 20 pages not only had Ulysses failed to even board his spaceship, but I had no idea at all what on earth was going on. Verdict: Rubbish.

When an English/American writer try to explain his/her ideas about life(I mention ideas about meaning,purpose and philosophy of life)and when he/she try to do this with complicated ideas and long sentences(or like very short ones especially in this particular book);what his/her work become to is:A tremendous nonsense!!!

Thi’ got to be the worst, I- I – I mean the worst ever written book ever. Know why? ‘Cause he’ such a showoff, know what I MEAN? He’s ingenious I’ll giv’ ’em that, but ingenuity my friends tire and enervate. Get to the point and stick to it ‘s my motto.

This is one of those books that “smart” people like to “read.”

The grammar is so disjointed as to make it nearly impossible to read.

Ulysses is basically an unbridled attack on the very ideas of heroism, romantic love and sexual fulfillment, and objective literary expression.

What’s with all the foreign languages?

It has no real meaning.

It is a blasphemy that it ever was published.

Anyone who tells you they’ve read this so-called book all the way through is probably lying through their teeth.It is impossible to endure this torture.

A babbling, senseless tome upheld by “literary luminaries” who fear being cast into the tasteless bourgeois darkness for dissent? Yes, that’s the gist.

I discovered that the novel was not what I though it would be.

Joyce is an aesthetic bother of Marcel Duchamp (known for The Fountain, a urinal, now a museum piece) and John Cage (the composer of pieces for prepared piano, where the piano’s strings are mangled with trash.

Two positive things I can say about James Joyce is that he has a great sounding name and he gives wonderful titles to his works.

Ask yourself – are you going to enjoy a book that neccesitates your literature teacher lie next to you and explain its ‘sophistication’ to you ?

It’s the worst book which has ever been written.

Unless you really hate yourself, do not attempt to read this book.

The truth is this book stinks. For one thing it is vulgar, which, I hate to disappoint anyone, requires no talent at all. This is a talent any six year-old boy possesses.

The book is not so good, it is boring, it is a colection of words and a continuous experimentation of styles that, unhappily, do not mean anything to the meaning of the story; that is, the book’s language is snobbish and useless. Those who say that “love” such a writing are to be thought about as non-readers or as victims of a literary abnormality.

…the single most destructive piece of Literature ever written…

I’m all for challenging reads, but not for gibberish which academics persist in labeling erudition.

This book is extremely dull!!! My book club decided to read this book after one of the members visited the James Joyce tower in Ireland, which the author supposedly wrote part of the book in.

Ulysses is a failed novel because Joyce was a bad writer (shown by his other works).

In conclusion, Don’t read the book. Burn it hard. Do not let your children read the book—it will mutilate their brain cells.