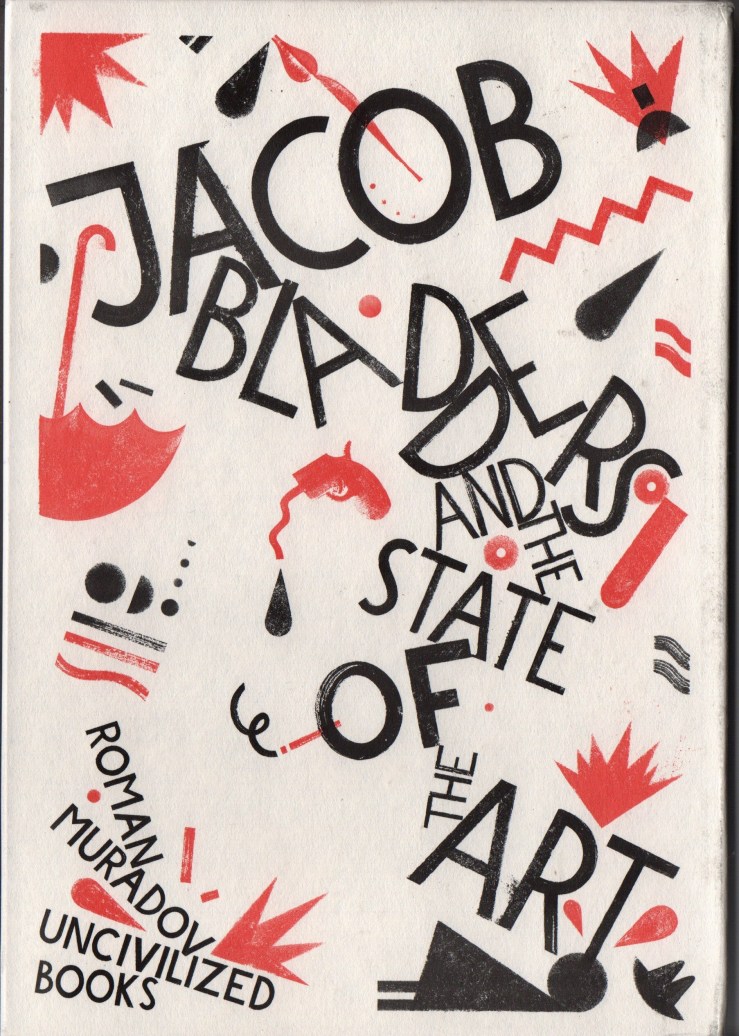

Roman Muradov’s newest graphic novella, Jacob Bladders and the State of the Art (Uncivilized Books, 2016), is the brief, shadowy, surreal tale of an illustrator who’s robbed of his artwork by a rival.

There’s more of course.

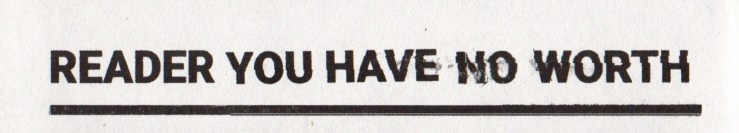

In a sense though, the plot is best summarized in the first line of Jacob Bladders:

Okay.

Maybe that’s too oblique for a summary (or not really a summary at all, if we’re being honest).

But it’s a fucking excellent opening line, right?

Like I said, “There’s more” and if the more—the plot—doesn’t necessarily cohere for you on a first or second reading, don’t worry. You do have worth, reader, and Muradov’s book believes that you’re equipped to tangle with some murky noir and smudgy edges. (It also trusts your sense of irony).

The opening line is part of a bold, newspaperish-looking introduction that pairs with a map. This map offers a concretish anchor to the seemingly-abstractish events of Jacob Bladders.

The map isn’t just a plot anchor though, but also a symbolic anchor, visually echoing William Blake’s Jacob’s Ladder (1805). Blake’s illustration of the story from Genesis 28:10-19 is directly referenced in the “Notes” that append the text of Jacob Bladders. There’s also a (meta)fictional “About the Author” section after the end notes (“Muradov died in October of 1949”), as well as twin character webs printed on the endpapers.

Along with the intro and map, these sections offer a set of metatextual reading rules for Jacob Bladders. The map helps anchor the murky timeline; the character webs help anchor the relationships between Muradov’s figures (lots of doppelgänger here, folks); the end notes help anchor Muradov’s satire.

These framing anchors are ironic though—when Muradov tips his hand, we sense that the reveal is actually another distraction, another displacement, another metaphor. (Sample end note: “METAPHOR: A now defunct rhetorical device relying on substitution of a real-life entity with any animal”).

It’s tempting to read perhaps too much into Jacob Bladder’s metatextual self-reflexivity. Here is writing about writing, art about art: an illustrated story about illustrating stories. And of course it’s impossible not to ferret out pseudoautobiographical morsels from the novella. Roman Muradov is, after all, a working illustrator, beholden to publishers, editors, art-directors, and deadlines. (Again from the end notes: “DEADLINE: A fictional date given to an illustrator to encourage timely delivery of the assignment. Usually set 1-2 days before the real (also known as ‘hard’) deadline”). If you’ve read The New Yorker or The New York Times lately, you’ve likely seen Muradov’s illustrations.

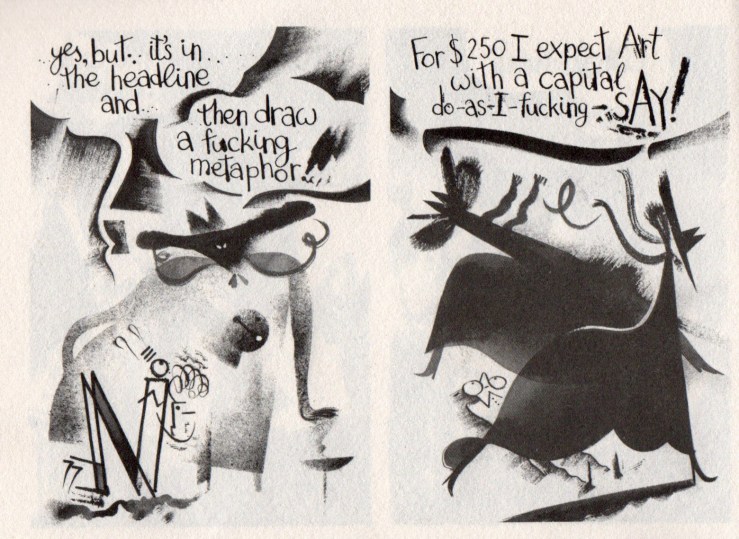

So what to make of the section of Jacob Bladders above? Here, a nefarious publisher commands a hapless illustrator to illustrate a “career ladders” story without using an illustration of a career ladder (From the end notes: “CAREER LADDER: An illustration of a steep ladder, scaled by an accountant in pursuit of a promotion or a raise. The Society of Illustrators currently houses America’s largest collection of career ladders, including works by M.C. Escher, Balthus, and Marcel Duchamp”).

Draw a fucking metaphor indeed. (I love how the illustrator turns into a Cubist cricket here).

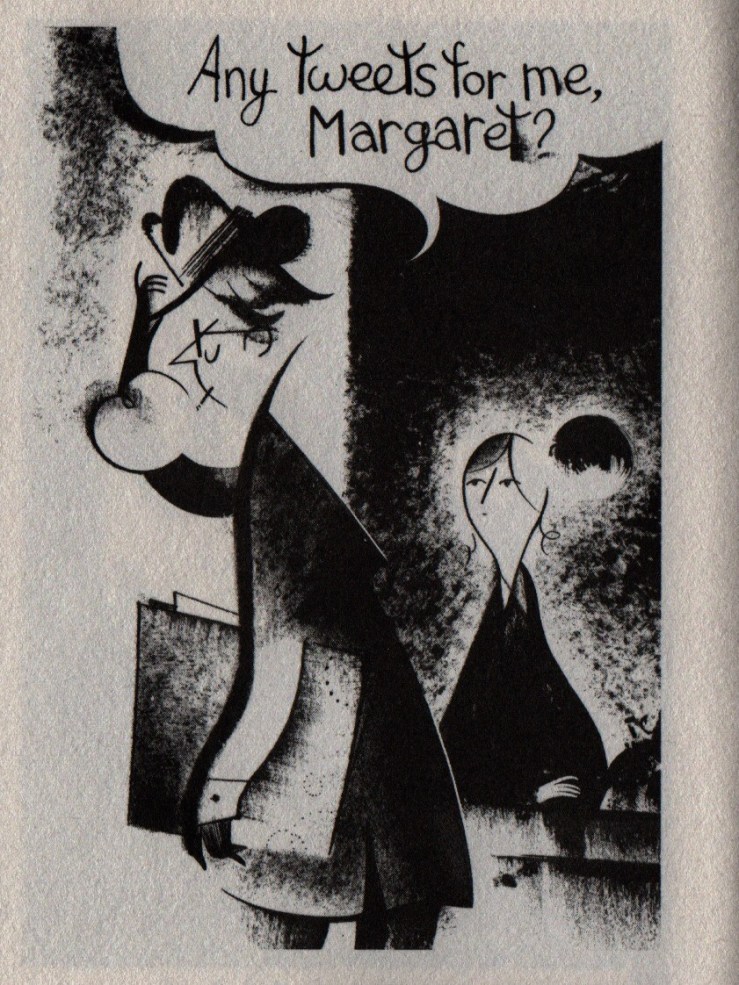

Again, it’s hard not to find semi-autobiographical elements in Jacob Bladders’s publishing satire. Muradov couches these elements in surreal transpositions. The first two panels of the story announce the setting: New York / 1947—but just a few panels later, the novella pulls this move:

Here’s our illustrator-hero Jacob Bladders asking his secretary (secretary!) for “any tweets”; he seems disappointed to have gotten “just a retweet.” In Muradov’s transposition, Twitter becomes “Tweeter,” a “city-wide messaging system, established in 1867” and favored by writers like E.B. White and Dorothy Parker.

Do you follow Muradov on Twitter?

I do. Which makes it, again, kinda hard for me not to root out those autobiographical touches. (He sometimes tweets on the illustration biz, y’see).

But I’m dwelling too much on these biographical elements I fear, simply because, it’s much, much harder to write compellingly about the art of it all, of how Muradov communicates his metatextual pseudoautobiographical story. (Did I get enough postmoderny adjectives in there? Did I mention that I think this novella exemplary of post-postmodernism? No? These descriptions don’t matter. Look, the book is fucking good).

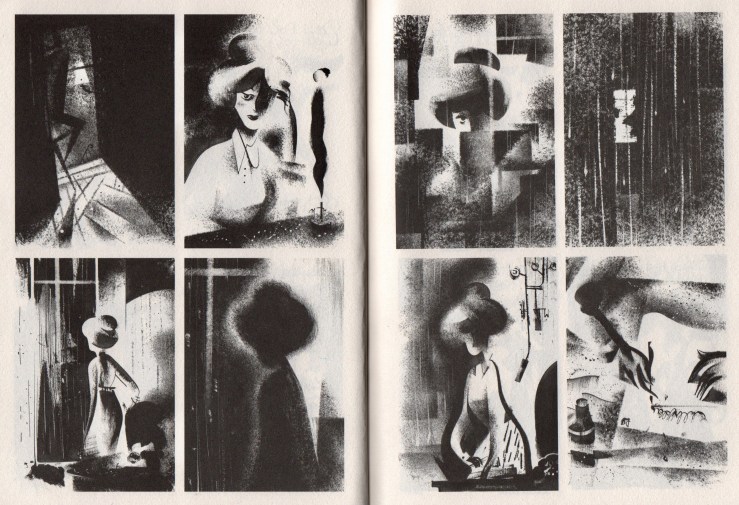

Muradov’s art is better appreciated by, like, looking at it instead of trying to describe it (this is an obvious thing to write). Look at this spread (click on it for biggeration):

The contours, the edges, the borders. The blacks, the whites, the notes in between. This eight-panel sequence gives us insides and outsides, borders and content, expression and impression. Watching, paranoia, a framed consciousness.

And yet our reading rules—again, from the end notes: “SPOTILLO: Spot illustration. Most commonly a borderless ink drawing set against white background”; followed by “CONSTRAINT: An arbitrary restriction imposed on a work of art in order to give it an illusion of depth”.

Arbitrary? Maybe. No. Who cares? Look at the command of form and content here, the mix and contrast and contradistinctions of styles: Cubism, expressionism, impressionism, abstraction: Klee, Miro, Balthus, Schjerfbeck: Robert Wiene and Fritz Lang. Etc. (Chiaroscuro is a word I should use somewhere in this review).

But also cartooning, also comix here—Muradov’s jutting anarchic tangles, often recoiling from the panel proper, recall George Herriman’s seminal anarcho-strip Krazy Kat. (Whether or not Muradov intends such allusions is not the point at all. Rather, what we see here is a continuity of the form’s best energies). Like Herriman’s strip, Muradov’s tale moves under the power of its own dream logic (more of a glide here than Herriman’s manic skipping).

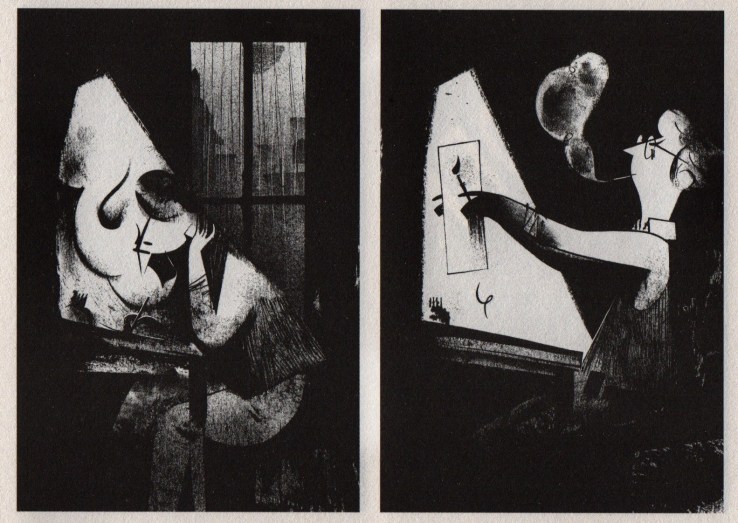

That dream logic follows the lead (lede?!) of that famous Romantic printmaker and illustrator William Blake, whose name is the last “spoken” word of the narrative (although not the last line in this illustrated text). Blake is the illustrator of visions and dreams—visions of Jacob’s Ladder, Jacob Bladders. Jacob Bladders and the State of the Art culminates in the Romantic/ironic apotheosis of its hero. The final panels are simultaneously bleak and rich, sad and funny, expressive and impressive. Muradov ironizes the creative process, but he also points to it as an imaginative renewal. “Imagination is the real,” William Blake advised us, and Muradov, whether he’d admit it or not, makes imagination real here. Highly recommended.