He was right, because during our time there was no one who doubted the legitimacy of his history, or anyone who could have disclosed or denied it because we couldn’t even establish the identity of his body, there was no other nation except the one that had been made by him in his own image and likeness where space was changed and time corrected by the designs of his absolute will, reconstituted by him ever since the most uncertain origins of his memory as he wandered at random through that house of infamy where no happy person had ever slept, as he tossed cracked corn to the hens who pecked around his hammock and exasperated the servants with orders he pulled out of the air to bring me a lemonade with chopped ice which he had left within reach of his hand, take that chair away from over there and put it over there, and they should put it back where it had been in order to satisfy in that minute way the warm embers of his enormous addiction to giving orders, distracting the everyday pastimes of his power with the patient raking up of ephemeral instants from his remote childhood as he nodded sleepily under the ceiba tree in the courtyard, he would wake up suddenly when he managed to grasp a memory like a piece in a limitless jigsaw puzzle of the nation that lay before him, the great, chimerical, shoreless nation, a realm of mangrove swamps with slow rafts and precipices that had been there before his time when men were so bold that they hunted crocodiles with their hands by placing a stake in their mouths, like that, he would explain to us holding his forefinger against his palate, he told us that on one Good Friday he had heard the hullabaloo of the wind and the scurf smell of the wind and he saw the heavy clouds of locusts that muddied the noonday sky and went along scissoring off everything that stood in their path and left the world all sheared and the light in tatters as on the eve of creation, because he had seen that disaster, he had seen a string of headless roosters hanging by their feet and bleeding drop by drop from the eaves of a house with a broad and crumbling sidewalk where a woman had just died, barefoot he had left his mother’s hand and followed the ragged corpse they were carrying off to bury without a coffin on a cargo litter that was lashed by the blizzard of locusts, because that was what the nation was like then, we didn’t even have coffins for the dead, nothing, he had seen a man who had tried to hang himself with a rope that had already been used by another hanged man from a tree in a village square and the rotted rope broke before it was time and the poor man lay in his death throes on the square to the horror of the ladies coming out of mass, but he didn’t die, they beat him awake with sticks without bothering to find out who he was because in those days no one knew who was who if he wasn’t known in the church, they stuck his ankles between the planks of the stocks and left him there exposed to the elements along with other comrades in suffering because that was what the times of the Goths were like when God ruled more than the government, the evil times of the nation before he gave the order to chop down all trees in village squares to prevent the terrible spectacle of a Sunday hanged man, he had prohibited the use of public stocks, burial without a coffin, everything that might awaken in one’s memory the ignominious laws that existed before his power, he had built the railroad to the upland plains to put an end to the infamy of mules terrified by the edges of precipices as on their backs they carried grand pianos for the masked balls at the coffee plantations, for he had also seen the disaster of the thirty grand pianos destroyed in an abyss and of which they had spoken and written so much even outside the country although only he could give truthful testimony, he had gone to the window by chance at the precise moment in which the rear mule had slipped and had dragged the rest into the abyss, so that no one but he had heard the shriek of terror from the cliff-flung mule train and the endless chords of the pianos that fell with it playing by themselves in the void, hurtling toward the depths of a nation which at that time was like everything that had existed before him, vast and uncertain, to such an extreme that it was impossible to know whether it was night or day in the kind of eternal twilight of the hot steamy mists in the deep canyons where the pianos imported from Austria had broken up into fragments, he had seen that and many other things in that remote world although not even he himself could have been sure with no room for doubt whether they were his own memories or whether he had heard about them on his bad nights of fever during the wars or whether he might have seen them in prints in travel books over which he would linger in ecstasy for long hours during the dead doldrums of power, but none of that mattered, God damn it, they’ll see that with time it will be the truth, he would say, conscious that his real childhood was not that crust of uncertain recollections that he only remembered when the smoke from the cow chips arose and he forgot it forever except that he really had lived it during the calm waters of my only and legitimate wife Leticia Nazareno who would sit him down every afternoon between two and four o’clock at a school desk under the pansy bower to teach him how to read and write, she had put her novice’s tenacity into that heroic enterprise and he matched it with his terrifying old man’s patience, with the terrifying will of his limitless power, with all my heart, so that he would chant with all his soul the tuna in the tin the loony in the bin the neat nightcap, he chanted without hearing himself or without anyone’s hearing him amidst the uproar of his dead mother’s aroused birds that the Indian packs the ointment in the can, papa places the tobacco in his pipe, Cecilia sells seals seeds seats seams scenes sequins seaweed and receivers, Cecilia sells everything, he would laugh, repeating amidst the clamor of the cicadas the reading lesson that Leticia Nazareno chanted to the time of her novice’s metronome, until the limits of the world became saturated with the creatures of your voice and in his vast realm of dreariness there was no other truth but the exemplary truths of the primer, there was nothing but the moon in the mist, the ball and the banana, the bull of Don Eloy, Otilia’s bordered bathrobe, the rote reading lessons which he repeated at every moment and everywhere just like his portraits even in the presence of the treasury minister from Holland who lost the thread of an official visit when the gloomy old man raised the hand with the velvet glove on it in the shadows of his unfathomable power and interrupted the audience to invite him to sing with me my mama’s a mummer, Ismael spent six months on the isle, the lady ate a tomato, imitating with his forefinger the beat of the metronome and repeating from memory Tuesday’s lesson with a perfect diction but with such a bad sense of the occasion that the interview ended as he had wanted it to with the postponement of payment of the Dutch debts for a more propitious moment, for when there would be time, he decided, to the surprise of the lepers, the blind men, the cripples who rose up at dawn among the rosebushes and saw the shadowy old man who gave a silent blessing and chanted three times with high-mass chords I am the king and the law is my thing, he chanted, the seer has fear of beer, a lighthouse is a very high tower with a bright beam which guides sailors at night, he chanted, conscious that in the shadows of his senile happiness there was no time but that of Leticia Nazareno of my life in the shrimp stew of the suffocating gambols of siesta time, there were no other anxieties but those of being naked with you on the sweat-soaked mattress under the captive bat of an electric fan, there was no light but that of your buttocks, Leticia, nothing but your totemic teats, your flat feet, your ramus of rue as a remedy, the oppressive Januaries of the remote island of Antigua where you came into the world one early dawn of solitude that was furrowed by the burning breeze of rotted swamps, they had shut themselves up in the quarters for distinguished guests with the personal order that no one is to come any closer than twenty feet to that door because I’m going to be very busy learning to read and write, so no one interrupted him not even with the news general sir that the black vomit was wreaking havoc among the rural population while the rhythms of my heart got ahead of the metronome because of that invisible force of your wild-animal smell, chanting that the midget is dancing on just one foot, the mule goes to the mill, Otilia washes the tub, kow is spelled with a jackass k, he chanted, while Leticia Nazareno moved aside the herniated testicle to clean him up from the last love-making’s dinky-poo, she submerged him in the lustral waters of the pewter bathtub with lion’s paws and lathered him with Reuter soap, scrubbed him with washcloths, and rinsed him off with the water of boiled herbs as they sang in duet ginger gibber and gentleman are all spelled with a gee, she would daub the joints of his legs with cocoa butter to alleviate the rash from his truss, she would put boric acid powder on the moldy star of his asshole and whack his behind like a tender mother for your bad manners with the minister from Holland, plap, plap, as a penance she asked him to permit the return to the country of the communities of poor nuns so they could go back to taking care of orphan asylums and hospitals and other houses of charity, but he wrapped her in the gloomy aura of his implacable rancor, never in a million years, he sighed, there wasn’t a single power in this world or the other that could make him go against a decision taken by himself alone and aloud, she asked him during the asthmas of love at two in the afternoon that you grant me one thing, my life, only one thing, that the mission territory communities who work on the fringes of the whims of power might return, but he answered her during the anxieties of his urgent husband snorts never in a million years my love, I’d rather be dead than humiliated by that pack of long skirts who saddle Indians instead of mules and pass out beads of colored glass in exchange for gold nose rings and earrings, never in a million years, he protested, insensitive to the pleas of Leticia Nazareno of my misfortune who had crossed her legs to ask him for the restitution of the confessional schools expropriated by the government, the disentailment of property held in mortmain, the sugar mills, the churches turned into barracks, but he turned his face to the wall ready to renounce the insatiable torture of your slow cavernous love-making before I would let my arm be twisted in favor of those bandits of God who for centuries have fed on the liver of the nation, never in a million years, he decided, and yet they did come back general sir, they returned to the country through the narrowest slits, the communities of poor nuns in accordance with his confidential order that they disembark silently in secret coves, they were paid enormous indemnities, their expropriated holdings were restored with interest and the recent laws concerning civil marriage, divorce, lay education were repealed, everything he had decreed aloud during his rage at the comic carnival of the process of the declaration of sainthood for his mother Bendición Alvarado may God keep her in His holy kingdom, God damn it, but Leticia Nazareno was not satisfied with all that but asked for more, she asked him to put your ear to the lower part of my stomach so that you can hear the singing of the creature growing inside, because she had awakened in the middle of the night startled by that deep voice that was describing the aquatic paradise of your insides furrowed by mallow-soft sundowns and winds of pitch, that interior voice that spoke to her of the polyps on your kidneys, the soft steel of your intestines, the warm amber of your urine sleeping in its springs, and to her stomach he put the ear that was buzzing less for him and he heard the secret bubbling of the living creature of his mortal sin, a child of our obscene bellies who would be named Emanuel, which is the name by which other gods know God, and on his forehead he will have the white star of his illustrious origins and he will inherit his mother’s spirit of sacrifice and his father’s greatness and his own destiny of an invisible conductor, but he was to be the shame of heaven and the stigma of the nation because of his illicit nature as long as he refused to consecrate at the altar what he had vilified in bed for so many years of sacrilegious concubinage, and then he opened a way through the foam of the ancient bridal mosquito netting with that snort of a ship’s boiler coming from the depths of his terrible repressed rage shouting never in a million years, better dead than wed, dragging his great feet of a secret bridegroom through the salons of an alien house whose splendor of a different age had been restored after the long period of the shadows of official mourning, the crumbling holy-week crepe had been pulled from the cornices, there was sea light in the bedrooms, flowers on the balconies, martial music, and all of it in fulfillment of an order that he had not given but which had been an order of his without the slightest doubt general sir because it had the tranquil decision of his voice and the unappealable style of his authority, and he approved, agreed, and the shuttered churches opened again, and the cloisters and cemeteries were returned to their former congregations by another order of his which he had not given either but he approved, agreed, the old holy days of obligation had been restored as well as the practices of lent and in through the open balconies came the crowd’s hymns of jubilation that had previously been sung to exalt his glory as they knelt under the burning sun to celebrate the good news that God had been brought in on a ship general sir, really, they had brought Him on your orders, Leticia, by means of a bedroom law which she had promulgated in secret without consulting anybody and which he approved in public so that it would not appear to anyone’s eyes that he had lost the oracles of his authority, for you were the hidden power behind those endless processions which he watched in amazement through the windows of his bedroom as they reached a distance beyond that of the fanatical hordes of his mother Bendición Alvarado whose memory had been erased from the time of men, the tatters of her bridal dress and the starch of her bones had been scattered to the winds and in the crypt the stone with the upside-down letters had been turned over so that even the mention of her name as a birdwoman painter of orioles in repose would not endure till the end of time, and all of that by your orders, because you were the one who had ordered it so that no other woman’s memory would cast a shadow on your memory, Leticia Nazareno of my misfortune, bitch-daughter.

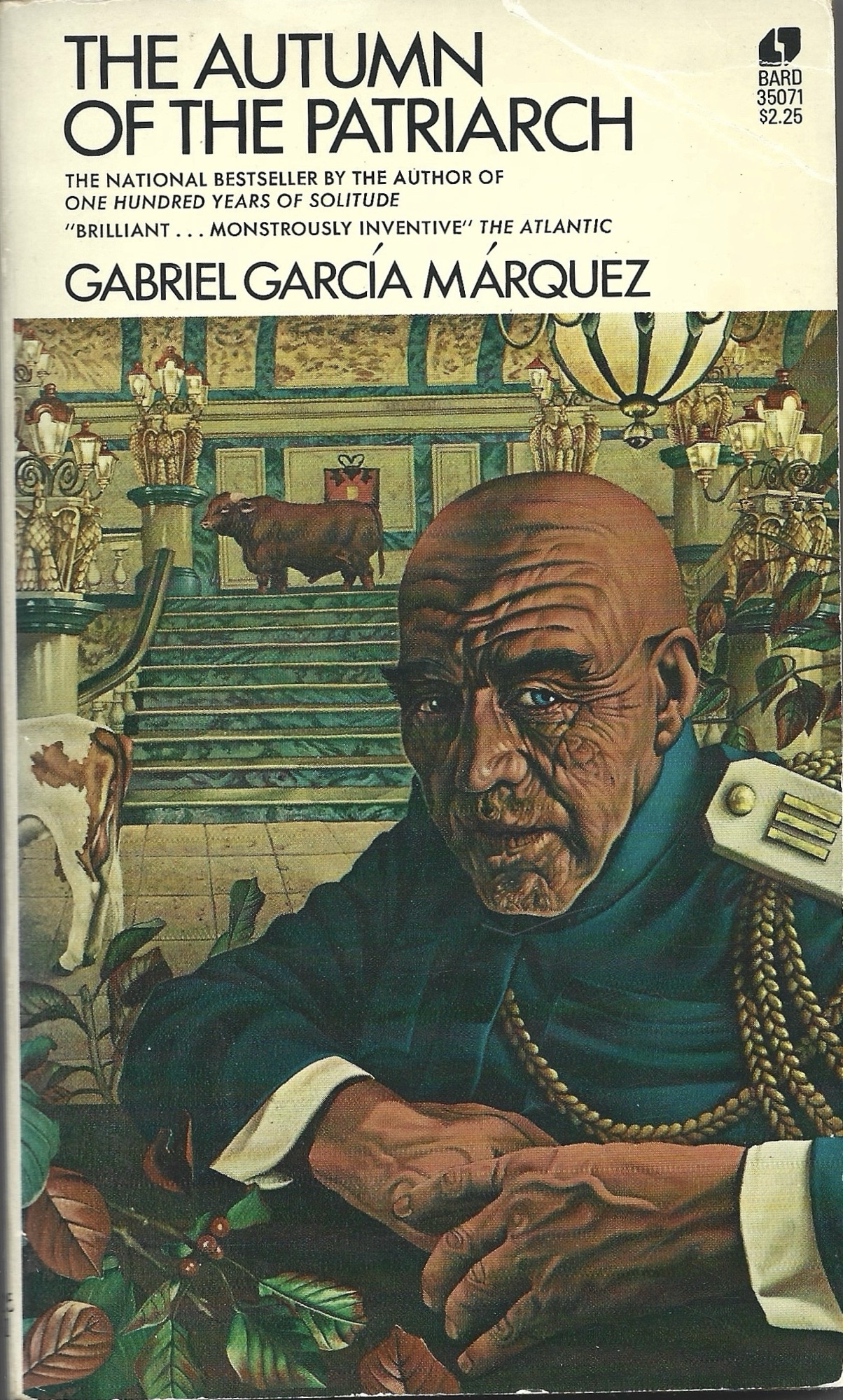

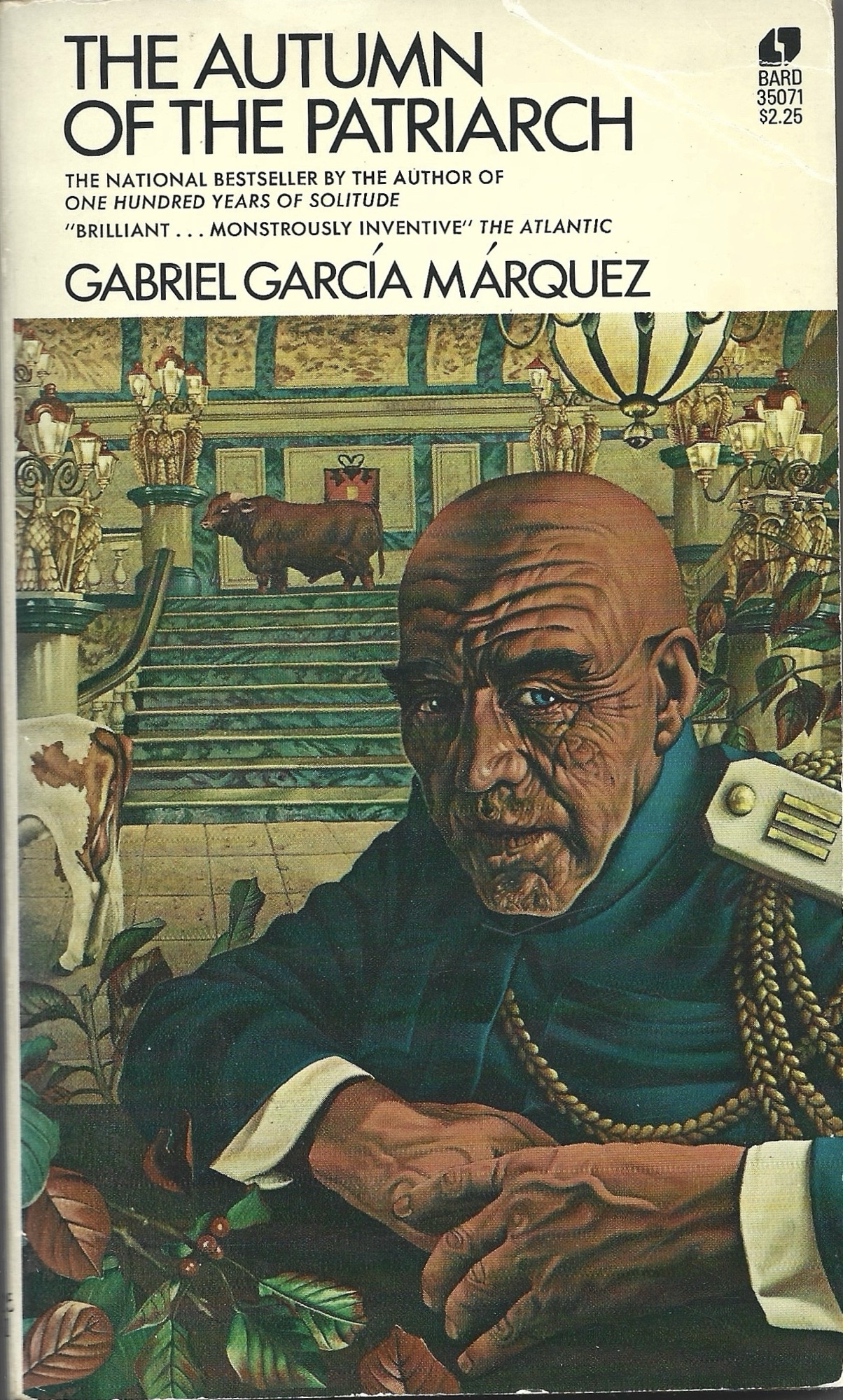

From Gabriel García Márquez’s The Autumn of the Patriarch in translation by Gregory Rabassa.