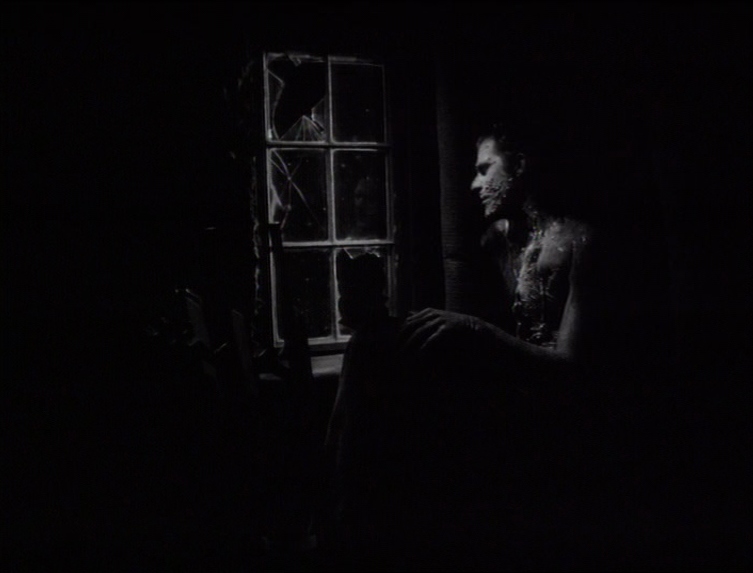

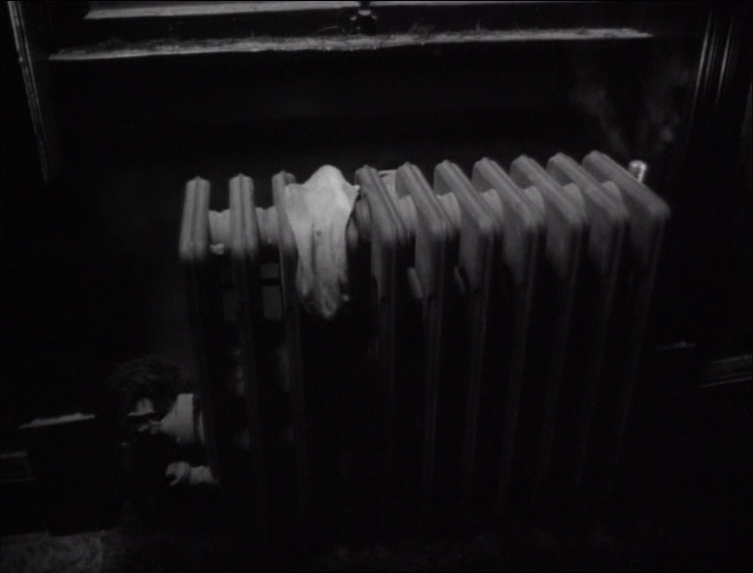

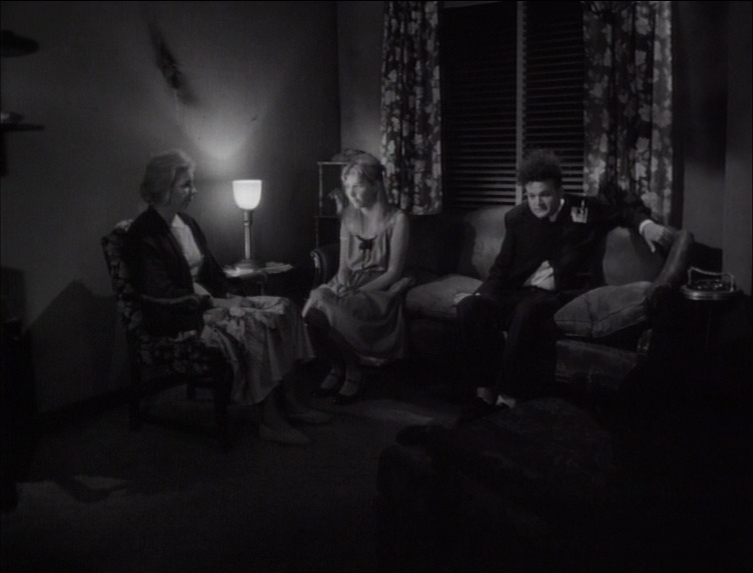

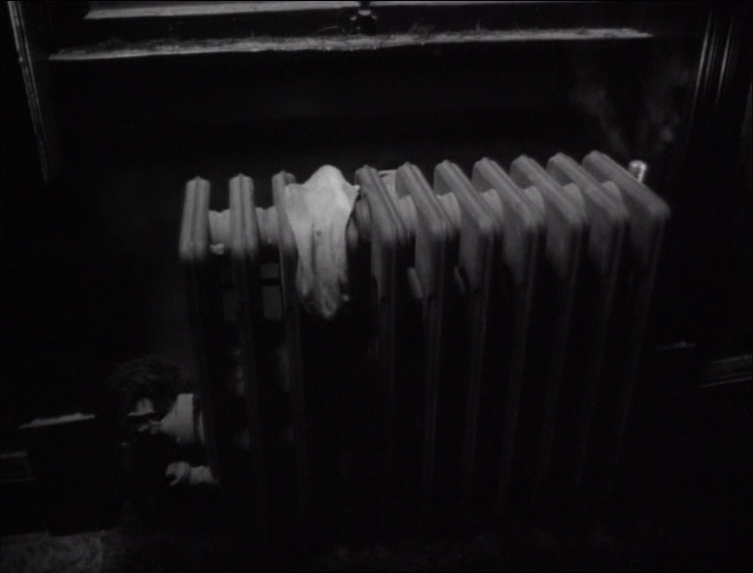

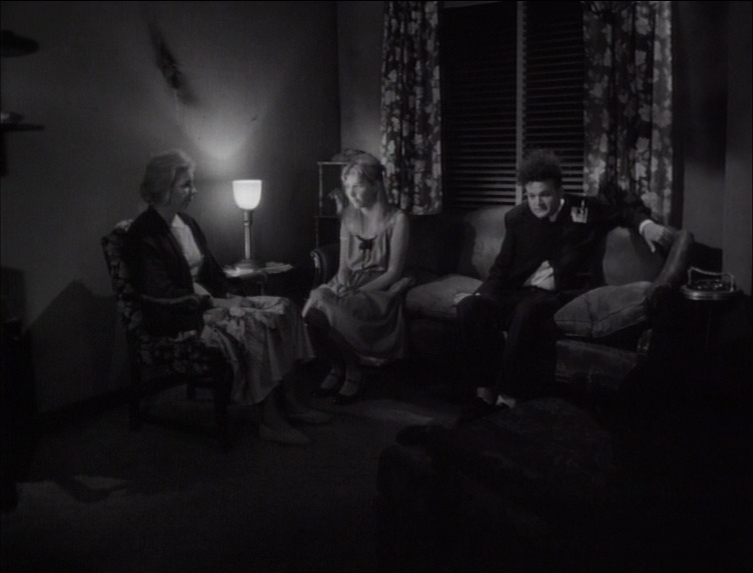

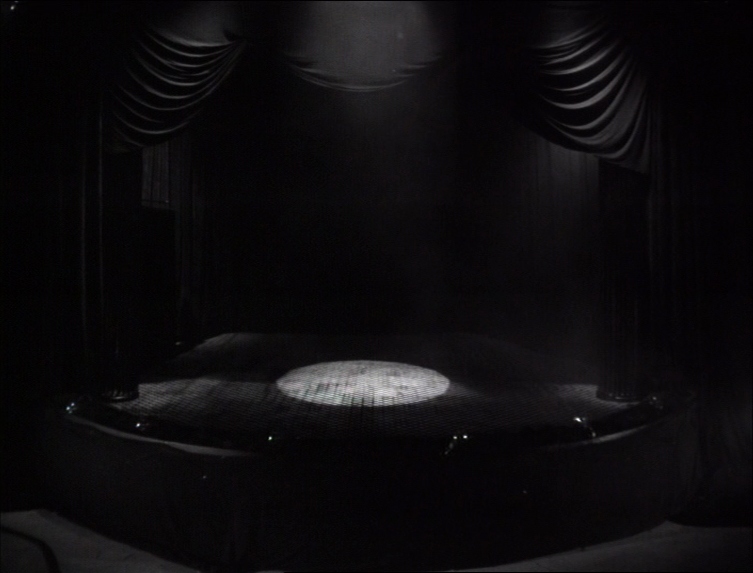

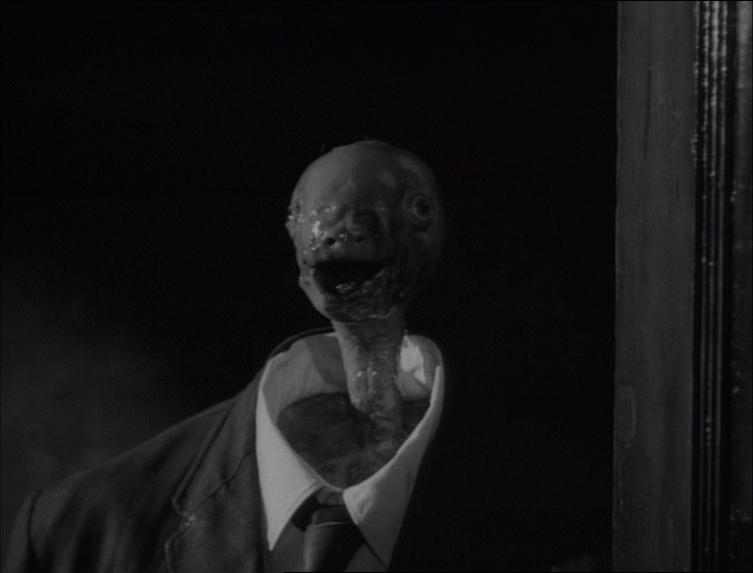

From Eraserhead, 1977. Directed by David Lynch with cinematography by Frederick Elmes and Herbert Cardwell. Via Film Grab.

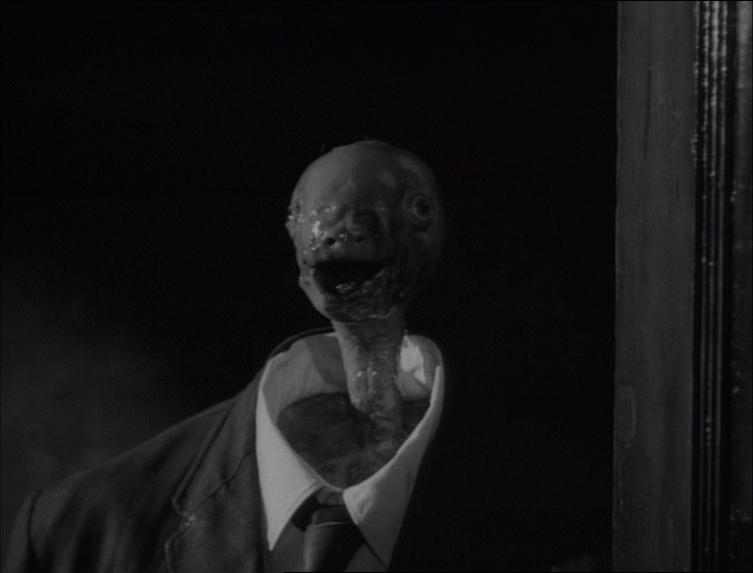

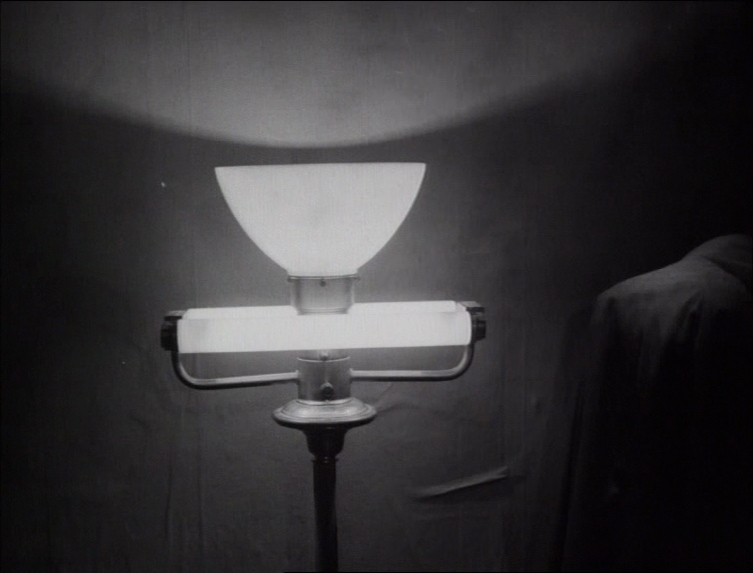

From Eraserhead, 1977. Directed by David Lynch with cinematography by Frederick Elmes and Herbert Cardwell. Via Film Grab.

RIP David Lynch, 1946-2025

We weirdos lost a spiritual uncle today.

Lose isn’t exactly the right word–the work is still there, the tremendous body of works, the films and images that I’ve returned to for so much of my life, films and images my fourteen-year-old son has recently been drawn to himself, wholly independent of me, getting there through his own weird back channels, my son who asked me just the other day if we could watch Eraserhead, and I said, Not yet, although I was the same age as he is now when I watched Eraserhead and let it do something weird to me. Maybe we’ll start with The Elephant Man instead, let it break his heart a little. Keep him away from Fire Walk With Me until he can handle it (you can never really handle it). I saw them all too young. Was way too young when my older cousin showed me Blue Velvet; I think it imprinted on me. Rewatching it (for the fifth? tenth?) time a decade and a half later, I realized I was Kyle M’s Jeffrey Beaumont peering through the closet in horror at the Adult World. Maybe I wasn’t too young. But I’ve loved them all, again and again—Lost Highway, the first one I got to see in a theater, Mulholland Dr. (the best one?), Inland Empire (really the best one). Even Dune, the first one I saw, perplexed as hell. My parents let us watch it again and again on VHS and it always refused to cohere. I think they thought it was like Star Wars, which it both was and very much wasn’t. Even the straight one he made for the normies (especially the one he made for the normies–although I don’t know if they appreciated it). But really, especially, when he Got the Old Gang Back Together for Twin Peaks: The Return—it was such a gift, a gift that seemed to come out of nowhere, unexpected, but I think even then we could recognize what a beautiful gift it was — even if it broke my heart all over again at the end, in the best possible way (“What year is this?” / “Laura!” / HOWL). I think we all knew to say Thank you then; I think we showed our love in return for the artist’s gifts. I’m thankful now, sad, selflishly sad that there won’t be one more gift, one more vision that could never come from another mind. But thankful.

“What Do I Need to Paint a Picture?”

by

Ithell Colquhoun

From Surrealist Women: An International Anthology (ed. Penelope Rosemont)

Certainly not a canvas or an easel, because I need first a resistant surface (wall or panel) and a steady support (wall or table or bench). I like the surface on which I paint to be as near that of polished ivory as possible; sometimes this surface is so lovely that it seems a pity to paint it at all. Then I need a number, but not a large number, of opaque pigments and a small amount of medium, I am not going to say what is in the medium, but it smells very nice. Then a still smaller number of transparent pigments, and lastly a surfacing-wax which I put on when the paint is dry and which also smells very nice.

I need a line to work to (Blake’s “bounding outline”); that means a full-sized detailed drawing afterwards traced. Then I put on the opaque colors very smooth and finally the glazes, if any, with the transparent colors. These are only the fixed and the cardinal qualities; what of the mutable? What of inspiration? What can one say of it except that it comes and goes, is helped and hindered, is unbiddable and unpredictable?

As to results, I aim for them to be sculptural: drawing and painting are branches of sculpture. For me, drawing is two-dimensional sculpture, painting is two-dimensional colored sculpture. If I do any sculpture, it is colored.

Mine is a very convenient way of painting, because it needs so many consecutive hours of work that it is almost impossible to do anything else.

I got a review copy of Lawrence Venuti’s selection of Dino Buzzati short stories he’s translated as The Bewitched Bourgeois a few days before we left for a family vacation at the end of last year in Mexico City. I’d meant to take it with me, thinking that the (often very short) short stories would make ideal plane, airport, and I’m-exhausted-but-want-a-quick-brain-snack reading. But I ended up throwing José Donoso’s novel The Obscene Bird of Night into my ancient North Face Recon instead in a weird effort to get its last hundred and fifty pages “finished” before the so-called “next year.” I achieved that goal and am now rereading big chunks of The Obscene Bird of Night. I should have brought the Buzzati. I think it would have been ideal for my needs at the time, based on the handful of tales I’ve read so far.

Here’s NYRB’s blurb:

Dino Buzzati was a prolific writer of stories, publishing several hundred over the course of forty years. Many of them are fantastic—reminiscent of Kafka and Poe in their mixture of horror and absurdity, and at the same time anticipating the alternate realities of The Twilight Zone or Black Mirror in their chilling commentary on the barbarities, catastrophes, and fanaticisms of the twentieth century.

In The Bewitched Bourgeois, Lawrence Venuti has put together an anthology that showcases Buzzati’s short fiction from his earliest stories to the ones he wrote in the last months of his life. Some appear in English for the first time, while others are reappearing in Venuti’s crisp new versions, such as the much-anthologized “Seven Floors,” an absurdist tale of a patient fatally caught in hospital bureaucracy; “Panic at La Scala,” in which the Milanese bourgeoisie, fearing a left-wing revolution, find themselves imprisoned in the opera house; and “Appointment with Einstein,” where the physicist, stopping at a filling station in Princeton, New Jersey, encounters a gas station attendant who turns out to be the Angel of Death.

The Messenger, Charles Wright. Manor Books (1974). No cover artist or designer credited. 217 pages.

Charles Wright (not to be confused with Charles Wright or Charles Wright) published three novels between 1963 and 1973. His second novel, The Wig (1966) is an under-read, underappreciated gem—a tragicomic satire employing sharp distortions and cartoony edges. Wright’s first novel, The Messenger, is perhaps a bit too beholden to Richard Wright (to whom it is dedicated (along with Billie Holiday))—but many readers may prefer its raw realism to The Wig’s zany (and often crushing) zigs and zags. His last published novel, Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About, is the most accomplished and singular of the trio—fragmentary, polyglossic, kaleidoscopic, messy. The trio remains in print as an omnibus with an introduction by Ishmael Reed. Read Reed on reading Wright.

The Uncollected Stories of Mavis Gallant publishes later this month from NYRB. And oof is she a big boy! NYRB’s blurb:

Mavis Gallant’s extraordinary mastery of the short story remains insufficiently recognized. She may be the best writer of stories since the early-1950s prime of John Cheever, Eudora Welty, and Flannery O’Connor, and even in such august company, her work is sui generis. Gallant’s short fiction refines the art of the story even as it expands the boundaries of what a story can be. Above and beyond that, however, it constitutes a striking, almost avant-garde reduction. To read her is to discover something about the very nature of story: how for better or worse life is caught up in it, and how on the page that common predicament can come to life.

The Uncollected Stories of Mavis Gallant includes more than thirty stories never before gathered into one volume, including “The Accident” and “His Mother” and “An Autobiography” and “Dédé.” With the publication of this book, finally all of this modern master’s fiction will be in print.

“Whatever He Sees, He Sees Soft”

by

Julio Cortázar

translated by Robert Coover and Pilar Coover

I know a great softener, a fellow who, whatever he sees, he sees soft, softens it merely by seeing it, not by looking at it for he doesn’t look, he only sees, he goes around seeing things and all of them are terribly soft, which makes him happy because he doesn’t like hard things at all.

There was a time when no doubt he saw things hard, being then still able to look, for he who looks sees twice: he sees what he’s seeing and at the same time it is what he sees, or at least it could be, or would like to be, or would not like to be, all exceedingly philosophical and existential means of locating oneself and locating the world. But one day when he was about twenty years old, he began to stop looking, this fellow, because in point of fact he had very soft skin, and the last few times he’d wanted to look straight out at the world, the sight had torn his skin in two or three places, and naturally my friend said. Hey baby, this won’t do! Whereupon one morning he’d started just seeing instead, very carefully, only that, nothing but seeing-and from then on, of course, whatever he saw, he saw soft, softened it simply by seeing it, and he was happy because he couldn’t abide hard things at all.

“Trivializing vision” is what a professor from Bahía Blanca called it, a surprisingly felicitous expression coming as it did from Bahía Blanca, but my friend paid it no heed, and not only that, but when he saw the professor, he naturally saw him as remarkably soft, and so invited him home for cocktails, introduced him to his sister and aunt, the whole event transpiring in an atmosphere of great softness.

It bothers me a little, I must say, because whenever my friend sees me, I feel like I’m going completely soft, and even though I know it’s got nothing to do with me, but rather with the image of me my friend has, as the professor from Bahía Blanca would say, just the same it bothers me, because nobody likes to be seen as some kind of semolina pudding, and so get invited to the movies to watch cowboys or get talked to for hours about how lovely the carpets are in the Embassy of Madagascar.

What’s to be done with my friend? Nothing, of course, At all events, see him but never look at him: how, I ask, could we look at him without, horribly, risking utter dissolution? He who sees only must be seen only: a wise and melancholy moral which goes, I am afraid, beyond the laws of optics.

The Colossus of Maroussi, Henry Miller. Penguin Books (1964). Cover Osbert Lancaster. 248 pages.

From Miller’s The Colossus of Maroussi (1941):

At Arachova Ghika got out to vomit. I stood at the edge of a deep canyon and as I looked down into its depths I saw the shadow of a great eagle wheeling over the void. We were on the very ridge of the mountains, in the midst of a convulsed land which was seemingly still writhing and twisting. The village itself had the bleak, frostbitten look of a community cut off from the outside world by an avalanche. There was the continuous roar of an icy waterfall which, though hidden from the eye, seemed omnipresent. The proximity of the eagles, their shadows mysteriously darkening the ground, added to the chill, bleak sense of desolation. And yet from Arachova to the outer precincts of Delphi the earth presents one continuously sublime, dramatic spectacle. Imagine a bubbling cauldron into which a fearless band of men descend to spread a magic carpet. Imagine this carpet to be composed of the most ingenious patterns and the most variegated hues. Imagine that men have been at this task for several thousand years and that to relax for but a season is to destroy the work of centuries. Imagine that with every groan, sneeze or hiccough which the earth vents the carpet is grievously ripped and tattered. Imagine that the tints and hues which compose this dancing carpet of earth rival in splendor and subtlety the most beautiful stained glass windows of the mediaeval cathedrals. Imagine all this and you have only a glimmering comprehension of a spectacle which is changing hourly, monthly, yearly, millennially. Finally, in a state of dazed, drunken, battered stupefaction you come upon Delphi. It is four in the afternoon, say, and a mist blowing in from the sea has turned the world completely upside down. You are in Mongolia and the faint tinkle of bells from across the gully tells you that a caravan is approaching. The sea has become a mountain lake poised high above the mountaintops where the sun is sputtering out like a rum-soaked omelette. On the fierce glacial wall where the mist lifts for a moment someone has written with lightning speed in an unknown script. To the other side, as if borne along like a cataract, a sea of grass slips over the precipitous slope of a cliff. It has the brilliance of the vernal equinox, a green which grows between the stars in the twinkling of an eye.

Seeing it in this strange twilight mist Delphi seemed even more sublime and awe-inspiring than I had imagined it to be. I actually felt relieved, upon rolling up to the little bluff above the pavilion where we left the car, to find a group of idle village boys shooting dice: it gave a human touch to the scene. From the towering windows of the pavilion, which was built along the solid, generous lines of a mediaeval fortress, I could look across the gulch and, as the mist lifted, a pocket of the sea became visible—just beyond the hidden port of Itea. As soon as we had installed our things we looked for Katsimbalis whom we found at the Apollo Hotel—I believe he was the only guest since the departure of H. G. Wells under whose name I signed my own in the register though I was not stopping at the hotel. He, Wells, had a very fine, small hand, almost womanly, like that of a very modest, unobtrusive person, but then that is so characteristic of English handwriting that there is nothing unusual about it.

By dinnertime it was raining and we decided to eat in a little restaurant by the roadside. The place was as chill as the grave. We had a scanty meal supplemented by liberal portions of wine and cognac. I enjoyed that meal immensely, perhaps because I was in the mood to talk. As so oft en happens, when one has come at last to an impressive spot, the conversation had absolutely nothing to do with the scene. I remember vaguely the expression of astonishment on Ghika’s and Katsimbalis’ faces as I unlimbered at length upon the American scene. I believe it was a description of Kansas that I was giving them; at any rate it was a picture of emptiness and monotony such as to stagger them. When we got back to the bluff behind the pavilion, whence we had to pick our way in the dark, a gale was blowing and the rain was coming down in bucketfuls. It was only a short stretch we had to traverse but it was perilous. Being somewhat lit up I had supreme confidence in my ability to find my way unaided. Now and then a flash of lightning lit up the path which was swimming in mud. In these lurid moments the scene was so harrowingly desolate that I felt as if we were enacting a scene from Macbeth. “Blow wind and crack!” I shouted, gay as a mud-lark, and at that moment I slipped to my knees and would have rolled down a gully had not Katsimbalis caught me by the arm. When I saw the spot next morning I almost fainted.

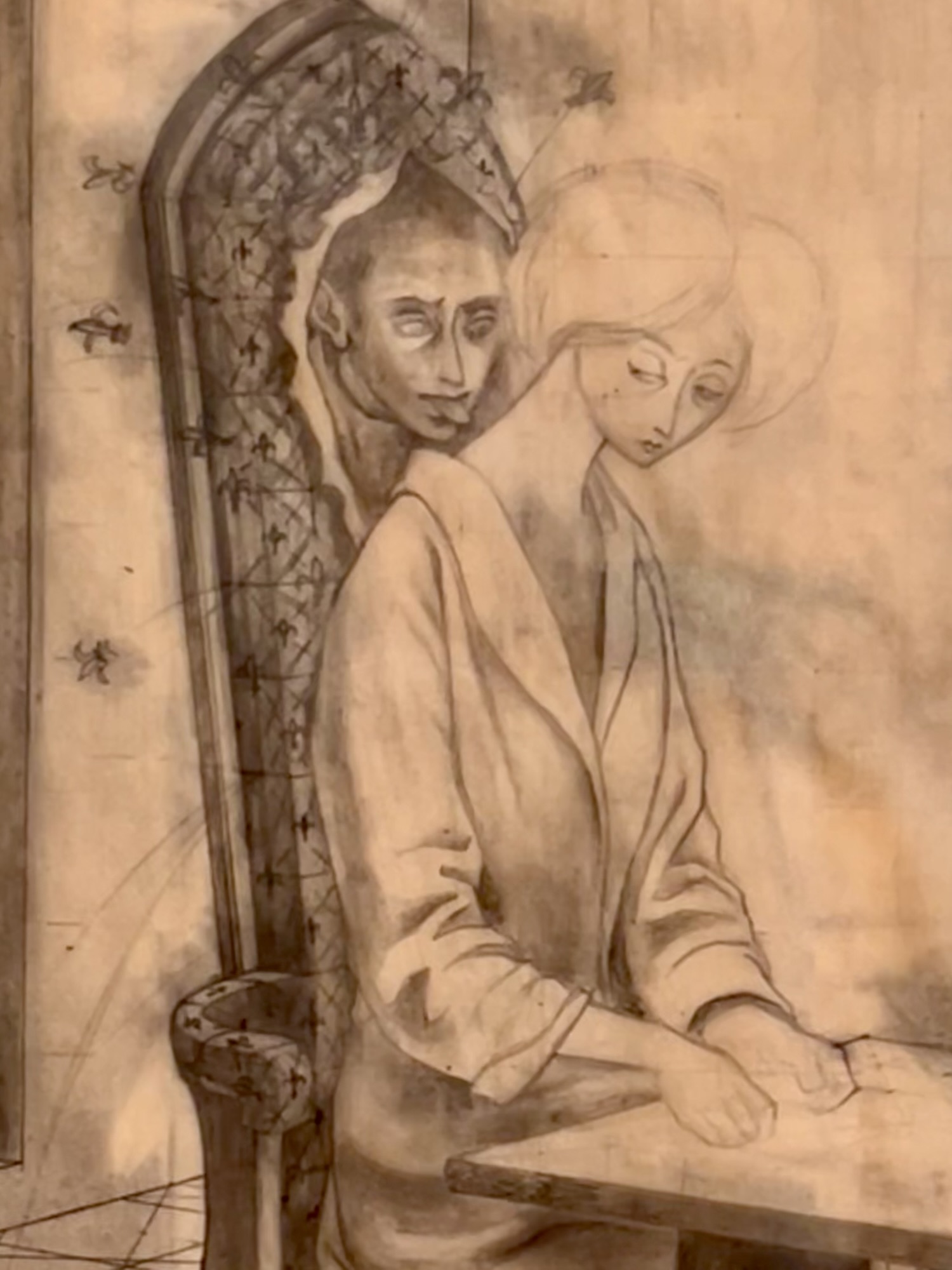

We enjoyed a lovely week between Christmas and New Year’s in Mexico City — great food, great people, great art. I especially enjoyed getting to see paintings by Remedios Varo, one of my favorite artists ever, at the Museo de Arte Moderno in Chapultepec Park.

Previously:

Not-really-the-rules recap:

I will focus primarily on novels here, or books of a novelistic/artistic scope.

I will include books published in English in 1975; I will not include books published in their original language in 1975 that did not appear in English translation until years later. So for example, Thomas Bernhard’s Korrektur will not appear on this list because although it was published in German in 1975, Sophie Wilkins’ English translation Correction didn’t come out until 1979.

I will not include English-language books published before 1975 that were published that year in the U.S.

I will fail to include titles that should be included, either through oversight or ignorance but never through malice. For example, I failed to include Dinah Brooke’s excellent 1973 novel Lord Jim at Home in my Best Books of 1973? post because I didn’t even know it existed until 2024. Please include titles that I missed in the comments.

So, what were some of the “Best Books of 1975?”

William Gaddis’s novel J R, one of the greatest 20th c. American novels, was published in 1975. I’ll make note of it first as an artistic ballast against the commercial list I’m about to offer up: The New York Times Best Seller list for 1975.

James Michener’s 1974 novel Centennial dominates the NYT list through winter and spring of 1975 (save for a brief one-week blip when Joseph Heller’s 1974 novel Something Happened published in paperback). By the summer, Arthur Hailey’s The Moneychangers rose to the top of the bestseller, the first novel of 1975 to do so. Judith Rossner’s Looking for Mr. Goodbar and E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime competed for the top slot throughout the fall of ’75, with Agatha Christie’s final Poirot novel Curtain taking over in the winter.

My sense is that of these bestsellers, Ragtime‘s critical reputation has probably endured the strongest. The editors of the NYT Book Review included Ragtime in their 28 Dec. 1975 year-end round-up, along with Donald Barthelme’s The Dead Father, Saul Bellow’s Humboldt’s Gift, Peter Handke’s A Sorrow Beyond Dreams, Peter Matthiessen’s Far Tortuga and V. S. Naipaul’s Guerrillas.

William Gaddis’s J R won the 1976 National Book Award for fiction; Paul Fussell’s The Great War and Modern Memory took the NBA for nonfiction; the NBA for poetry went to John Ashberry’s Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, and Walter D. Edmond’s Bert Breen’s Barn won the NBA for children’s literature. NBA finalists that year included Bellow’s Humboldt’s Gift, Vladimir Nabokov’s story collection Tyrants Destroyed, Johnanna Kaplan’s Other People’s Lives, Larry Woiwode’s Beyond the Bedroom Wall, and The Collected Stories of Hortense Calisher. (Robert Stone’s excellent 1974 novel Dog Soldiers won the 1975 NBA, if you’re keeping track).

If Bellow was sore about losing the NBA to Gaddis, he could console himself with the 1976 Pulitzer Prize for Literature (for Humboldt’s Gift). The 1975 Nobel Prize in Literature went to Eugenio Montale “for his distinctive poetry, which, with great artistic sensitivity, has interpreted human values under the sign of an outlook on life without illusions.” Montale did not publish a book in 1975.

The 1975 Booker Prize shortlisted only two of eighty-one novels (both published in 1975): Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Heat and Dust and Thomas Keneally’s Gossip From the Forest. Heat and Dust took the prize.

The American Library Association’s Notable Books of 1975 list echoes many of the titles we’ve already seen, as well as some interesting outliers: Andre Brink’s self-translation of Looking on Darkness (banned by South Africa’s apartheid government), Alan Brody’s Coming To, Ben Greer’s prison novel Slammer, Dagfinn Grønoset’s Anna (translated by Ingrid B. Josephson), Donald Harrington’s The Architecture of the Arkansas Ozarks, Anne Sexton’s The Awful Rowing toward God, and Mark Vonnegut’s memoir The Eden Express.

The National Book Critics Circle Awards for 1975 were Doctorow’s Ragtime, R.W.B. Lewis’s biography Edith Wharton, Ashbery’s Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, and Fussell’s The Great War and Modern Memory.

The 1975 Nebula Awards long list is particularly interesting. Along with sci-fi stalwarts like Poul Anderson, Alfred Bester, and Roger Zelzany, the Nebulas expanded their reach to include Doctorow’s Ragtime and Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. William Weaver’s translation of Invisible Cities was actually published in 1974 — as was the Nebula winner for 1975, Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War. Significant Nebula Awards shortlist titles published in 1975 include Joanna Russ’s The Female Man, Robert Silverberg’s The Stochastic Man, and Tanith Lee’s The Birthgrave. Most notable though is the inclusion of Samuel R. Delaney’s cult classic Dhalgren.

The 1976 Newberry Award went to Susan Cooper’s 1975 novel The Grey King; the Newberry Honor Titles were Sharon Bell Mathis’s The Hundred Penny Box (illustrated by Diane and Leo Dillon) and Laurence Yep’s Dragonwings. Other notable books for children and adolescents published in 1975 include Natalie Babbitt’s Tuck Everlasting, Beverly Cleary’s Ramona the Brave, and Roald Dahl’s Danny, the Champion of the World.

Awards aside, commercial successes for 1975 included Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot, Joseph Wambaugh’s The Choirboys, Jack Higgins’s The Eagle Has Landed, James Clavell’s Shōgun, Michael Crichton’s The Great Train Robbery, Lawrence Sanders’s Deadly Sins, and Anthony Hope’s The Prisoner of Zenda.

Some critical/cult favorites (and genre exercises) from 1975 include: Martin Amis’s Dead Babies, J.G. Ballard’s High-Rise, Malcolm Bradbury’s The History Man, Charles Bukowski’s Factotum, Rumer Godden’s The Peacock Spring, Xavier Herbert’s insanely-long epic Poor Fellow My Country, Gayl Jones’s Corregidora, David Lodge’s Changing Places, Bharati Mukherjee’s Wife, Gary Myers’s weirdo fiction collection The House of the Worm, Tim O’Brien’s debut Northern Lights, James Purdy’s In a Shallow Grave, James Salter’s Light Years, Anya Seton’s Smouldering Fires, Gerald Seymour’s Harry’s Game, Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson’s The Illuminatus! Trilogy, Glendon Swarthout’s The Shootist, and Jack Vance’s Showboat World.

I’ve only read about fifteen books mentioned here (although I’ve abandoned several of them more than once (I’m looking at you Illuminatus! Trilogy and Dhalgren), so my own “best of 1975” list is uninformed and provisional, and frankly pretty obvious to anyone who checks in on this blog semi-regularly. My picks for ’75: J R, William Gaddis; The Dead Father, Donald Barthelme; High-Rise, J.G. Ballard.

☉ indicates a reread.

☆ indicates an outstanding read.

In some cases, I’ve self-plagiarized some descriptions and evaluations from my old tweets and blog posts.

I have not included books that I did not finish or abandoned.

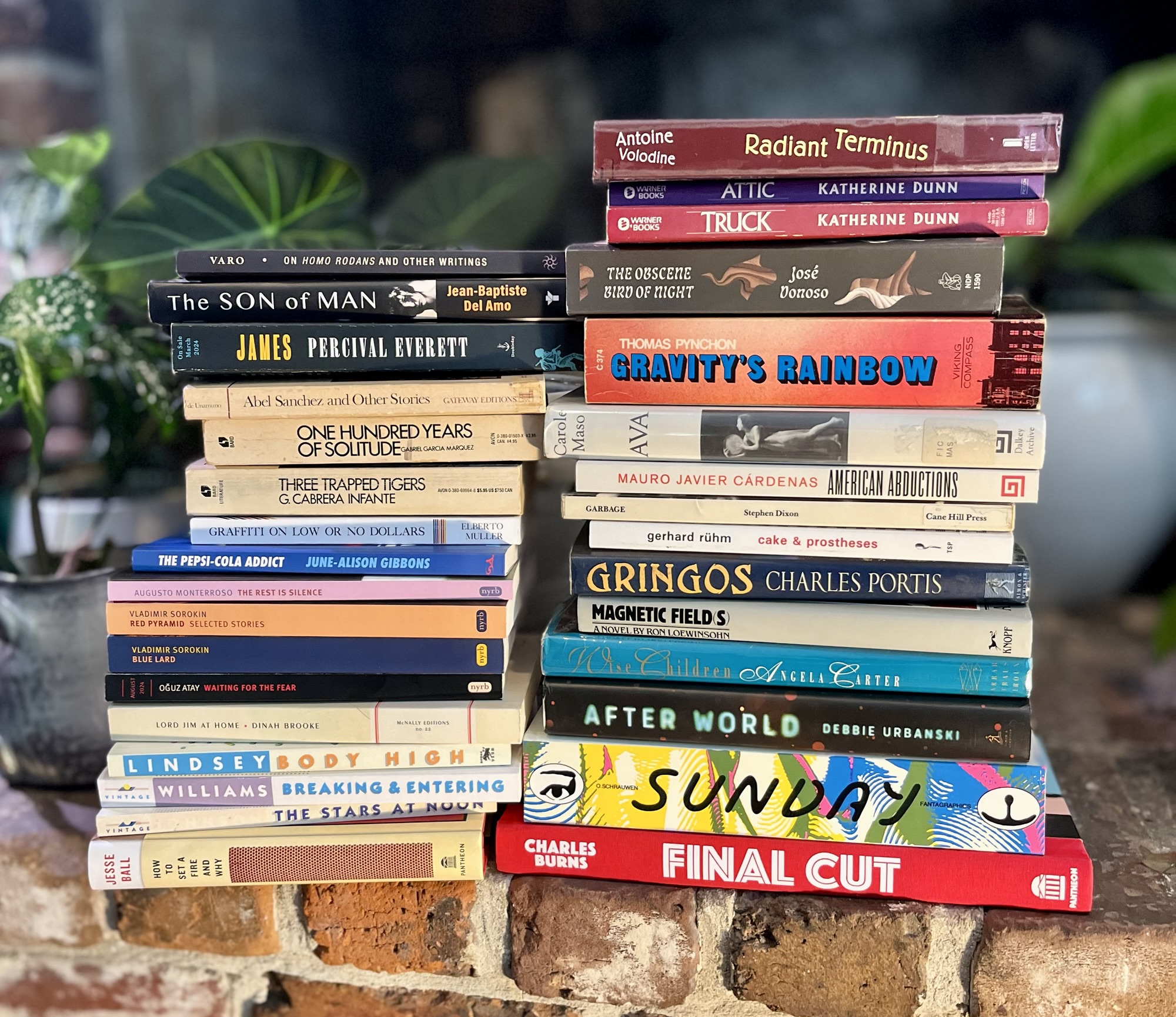

Cake & Prostheses, Gerhard Rühm; trans. Alexander Booth

Sexy, surreal, silly, and profound. Lovely little thought experiments and longer meditations into the weird.

Abel Sanchez and Other Stories, Miguel de Unamuno; trans. Anthony Kerrigan

Both sad and funny, Abel Sanchez, the 1917 novella that makes up the bulk of this volume, feels contemporary with Kafka and points towards the existentialist novels of Albert Camus

After World, Debbie Urbanski

Debbie Urbanski’s debut novel After World reimagines the end of humanity—or perhaps the beginning of a new digital existence. The narrator, [storyworker] ad39-393a-7fbc, reconstructs the life of Sen Anon, the last human archived in the Digital Human Archive Project, using sources like drones, diaries, and other materials. Drawing on tropes from dystopian and post-apocalyptic literature, this metatextual novel references authors like Octavia Butler and Margaret Atwood while nodding to works such as House of Leaves and Station Eleven. Urbanski’s spare, post-postmodern approach also reminded me of David Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress—good stuff.

Walking on Glass, Iain Banks

Walking on Glass weaves together three narrative threads: an art student’s infatuation, a paranoid-schizophrenic secret agent, and two ancient warriors trapped in a castle playing bizarre games. While the novel has some wonderful and funny moments, Banks’s debut The Wasp Factory is the stronger effort.

Red Pyramid, Vladimir Sorokin; trans. Max Lawton

If you’re interested in reading Sorokin but aren’t sure if you want to jump into the deep end with Blue Lard (or abject hell with Their Four Hearts), the collection Red Pyramid is a good starting place. In her blurb for the NYRB collection, Joy Williams describes Sorokin’s writing as “Extravagant, remarkable, politically and socially devastating, the tone and style without precedent, the parables merciless, the nightmares beyond outrance, the violence unparalleled.”

Ava, Carole Masso

The controlling intelligence of Carole Masso’s 1991 novel is the titular Ava, dying too young of cancer. Ava spools out in an elliptical assemblage of quips, quotes, observations, dream thoughts, and other lovely sad beautiful bits. Masso creates a feeling, not a story; or rather a story felt, intuited through fragmented language, experienced.

Dune, Frank Herbert☉

I have always remembered liking the first half of the first Dune novel and thinking that the book’s pacing, depth, and characterization falls apart in the second half. I thought the second of Villeneuve’s Dune films was so bad that I ended up listening to the audiobook to confirm if there was anything in the original material. The audit confirmed my suspicion that the first half of Dune is good—there’s a dinner scene that’s excellent—but the novel falls apart under its epic ambitions. Herbert is very good at writing about deceit, mind games, spycraft; he’s awful with action, legend, and myth.

Escape Velocity, Charles Portis

Charles Portis wrote five novels, all of which are excellent. He may have a perfect oeuvre. Escape Velocity collects some of his early journalism (he was on the Elvis beat for awhile, and then he covered the Civil Rights movement); there are also some short stories, a play, a few odds and ends. For completists only.

I Am Not Sidney Poitier, Percival Everett☆

A brilliant, picaresque satire that follows its absurdly named protagonist on a series of misadventures, washing the surreal in acid social commentary. A Candide for the cable teevee age.

The Einstein Intersection, Samuel R. Delaney

Shambolic and mythic, Delaney’s novel retells the story of Orpheus in a narrative style that mirrors the musician’s dismemberment and fragmentation.

Blue Lard, Vladimir Sorokin; trans. Max Lawton☉☆

I ended up writing seven riffs on this novel this spring.

Telephone, Percival Everett

I don’t know which version I read, but it was sad.

How to Set a Fire and Why, Jesse Ball

I reviewed it here, writing, that the narrator “Lucia’s voice is the reason to read How to Start a Fire. It’s compelling and funny and persuasive and hurt. It seems authentic, and I admire the risk Ball has taken—it’s not easy to write a teenage girl who is also a maybe-genius-and-would-be-arsonist.”

The Pepsi-Cola Addict, June-Alison Gibbons☆

Loved this one. From my review: “The Pepsi-Cola Addict is a strange and unsettling tale of teen angst that stands on its own as a small burning testament of adolescent creativity unspoiled by any intrusive ‘adult’ editorial hand.”

James, Percival Everett☆

James will likely end up on everyone’s year-end “best of”; to be clear it is mine. Everett’s novel joins a shortlist of strong responses to Adventures of Huckleberry Finn that includes Leslie Fiedler’s Love and Death in the American Novel, Cormac McCarthy’s Suttree, and Robert Coover’s Huck Out West.

Gravity’s Rainbow, Thomas Pynchon☉☆

The key to reading Gravity’s Rainbow is to read it once and then read it immediately again and post a series of silly annotations on your literary blog and then to read it again a year or two later and then a few years after that to listen to it on audiobook while you pressure wash your house and the shed you built a few years ago (with the help of your father-in-law and brother-in-law) and then repaint the house’s shutters and then invent a few other chores so you finish the audiobook. And then write two more annotation blogs about it, eight years after the first series.

Progress, Max Lawton

The Abode, Max Lawton

I’m the sliverest slightest bit wary to include Max Lawton’s novels here, as the versions I’ve read are not necessarily the ones that will publish—but they are big, bold, ambitious, and strange, and they left an incisor-sharp impression upon me this year. Progress is a “maybe-this-is-the-end-of-the-world?” catalog of horrors; The Abode is a self-deconstructing catalog of catalogs, bildungsroman, a (self-)love story.

Demian, Herman Hesse; trans. Michael Roloff and Michael Lebeck

We’ve all had a good great bad evil friend.

Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Robert Louis Stevenson☉☆

I made my family listen to Ian Holm read RLS’s Jekyll and Hyde on a four-hire drive and learned that “Jekyll” is pronounced with a long e and not the accustomed schwa — it rhymes with “treacle” not “freckle.” The book is much better and weirder than I remembered.

One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez; trans. Gregory Rabassa☉☆

Much, much sadder than I’d remembered. I’d registered One Hundred Years of Solitude as rich and mythic, its robust humor tinged with melancholy spiked with sex and violence. That memory is only partially correct—García Márquez’s novel is darker and more pessimistic than my younger-reader-self could acknowledge.

On Homo rodans and Other Writings, Remedios Varo; trans. Margaret Carson☉

The Son of Man, Jean-Baptiste Del Amo; trans. Frank Wynne

Enjoyed this one. From my review: “Del Amo gives us phenomena and response to that phenomena, but withholds the introspective logic of cause-and-effect or analysis that often dominates novels. Instead, he allows us to see what his characters see and to take from those sights our own interpretations.”

The Stars at Noon, Denis Johnson☉

A reread, but I honestly didn’t remember much about The Stars at Noon other than its premise and the fact that its narrator was an alcoholic journalist-cum-prostitute in Nicaragua. (That’s actually the premise.) It hadn’t made the same impression on me as other Johnson novels had when I went through a big Johnson jag in the late nineties and early 2000s, and I think that assessment was correct—it’s simply not as strong as Angels, Fiskadoro, or Jesus’ Son.

Radiant Terminus, Antoine Volodine, trans. Jeffrey Zuckerman☆

Excellent stuff; a highlight read of the year. From my review:

“Antoine Volodine’s novel Radiant Terminus is a 500-page post-apocalyptic, post-modernist, post-exotic epic that destabilizes notions of life and death itself. Radiant Terminus is somehow simultaneously fat and bare, vibrant and etiolated, cunning and naive. The prose, in Jeffrey Zuckerman’s English translation, shifts from lucid, plain syntax to poetical flights of invention. Volodine’s novel is likely unlike anything you’ve read before—unless you’ve read Volodine.”

Gringos, Charles Portis☉☆

Portis wrote five novels and all of them are perfect—but I think Gringos, his last, might be my favorite.

Lord Jim at Home, Dinah Brooke☆

Loved it. From my review:

“Lord Jim at Home is squalid and startling and nastily horrific. It is abject, lurid, violent, and dark. It is also sad, absurd, mythic, often very funny, and somehow very, very real for all its strangeness. The novels I would most liken Lord Jim at Home to, at least in terms of the aesthetic and emotional experience of reading it, are Ann Quin’s Berg, Anna Kavan’s Ice, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast novels, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, and James Joyce’s Portrait (as well as bits of Ulysses). (I have not read Conrad’s Lord Jim, which Brooke has taken as something of a precursor text for Lord Jim at Home.)”

American Abductions, Mauro Javier Cárdenas☆

Another favorite novel this year. From a riff back in October:

“If I were to tell you that Mauro Javier Cárdenas’s third novel is about Latin American families being separated by racist, government-mandated (and wholly fascist, really) mass deportations, you might think American Abductions is a dour, solemn read. And yes, Cárdenas conjures a horrifying dystopian surveillance in this novel, and yes, things are grim, but his labyrinthine layering of consciousnesses adds up to something more than just the novel’s horrific premise on its own. Like Bernhard, Krasznahorkai, and Sebald, Cárdenas uses the long sentence to great effect. Each chapter of American Abductions is a wieldy comma splice that terminates only when his chapter concludes—only each chapter sails into the next, or layers on it, really. It’s fugue-like, dreamlike, sometimes nightmarish. It’s also very funny. But most of all, it’s a fascinating exercise in consciousness and language—an attempt, perhaps, to borrow a phrase from one of its many characters, to make a grand ‘statement of missingnessness.'”

Attic, Katherine Dunn☆

Truck, Katherine Dunn

Katherine Dunn’s first novel Attic is seriously fucked up—like William Burroughs-Kathy Acker fucked up—an abject rant from a woman in prison in the mode of Ginsberg’s Howl. The narrator seems to be an autofictional version of Dunn herself, which is perhaps why Eric Rosenblum, in his 2022 New Yorker review described it as “largely a realist work in which Dunn emphasizes the trauma of her protagonist’s childhood.” Rosenblum uses the term realism two other times to describe Attic and refers to it at one point as a work of magical realism. If Attic is realism then so is Blood and Guts in High School. Her second novel Truck is equally weird, but it was maybe too much for me by the end.

Soldier of Mist, Gene Wolfe

Great premise, poor execution.

Final Cut, Charles Burns☆

In my review, I wrote that Final Cut served up “all the sinister dread and awful beauty that anyone following Burns’ career would expect, synthesized into his most lucid exploration of the inherent problems of artistic expression.”

Wise Children, Angela Carter

An enjoyable and maybe old-fashioned effort from Carter. I breezed through it, and remember it fondly.

Garbage, Stephen Dixon☆

I think Stephen Dixon’s novel Garbage was my favorite read of the year. I don’t know if it’s the best novel I read this year, but it was the most compelling—by which I mean it compelled me to keep reading, way too late some nights. From a thing I wrote a few months ago:

“I don’t know if Dixon’s Garbage is the best novel I’ve read so far this year, but it’s certainly the one that has most wrapped itself up in my brain pan, in my ear, throbbed a little behind my temple. The novel’s opening line sounds like an uninspired set up for a joke: ‘Two men come in and sit at the bar.’ Everything that unfolds after is a brutal punchline, reminiscent of the Book of Job or pretty much any of Kafka’s major works. These two men come into Shaney’s bar—this is, or at least seems to be, NYC in the gritty seventies—and try to shake him down to switch up garbage collection services. A man of principle, Shaney rejects their ‘offer,’ setting off an escalating nightmare, a world of shit, or, really, a world of garbage. I don’t think typing this description out does any justice to how engrossing and strange (and, strangely normal) Garbage is. Dixon’s control of Shaney’s voice is precise and so utterly real that the effect is frankly cinematic, even though there are no spectacular pyrotechnics going on; hell, at times Dixon’s Shaney gives us only the barest visual details to a scene, and yet the book still throbs with uncanny lifeforce. I could’ve kept reading and reading and reading this short novel; its final line serves as the real ecstatic punchline. Fantastic stuff.”

Graffiti on Low or No Dollars, Elberto Muller☆

A weirdo novel-in-riffs that I loved: bohemian hobo freight hopping, drug lore, art. Muller’s storytelling chops are excellent—he’s economical, dry, sometimes sour, and most of all a gifted imagist.

Galaxies, Barry N. Malzberg

Southern Comfort, Barry N. Malzberg (as “Gerold Watkins”)

A Satyr’s Romance, Barry N. Malzberg (as “Gerold Watkins”)

I really wanted to get into Galaxies, but I couldn’t. Malzberg’s faux-sci-fi metatextualist experiment carries his postmodernist anxiety of influence like a lance tilted against the would-be contemporaries who were more likely to get covered in The New York Times. His metamuscle is as strong as those folks, but you have to tell a story. I preferred the “erotic” novels I read that he wrote under the pseudonym Gerrold Watkins, 1969’s Southern Comfort and 1970’s A Satyr’s Romance.

The Singularity, Dino Buzzati; trans. Anne Milano Appel

From my review of The Singularity:

“Ultimately, The Singularity feels less like a novella than it does a short story stretched a bit too thin. Buzzati adroitly crafts an atmosphere of suspense and foreboding, but the characters are underdeveloped. Like a lot of pulp fiction, Buzzati’s book often reads as if it were written very quickly (and written expressly for money). Still, Buzzati’s intellect gives the book a philosophical heft, even if it sometimes comes through awkwardly in forced dialogue. Anne Milano Appel’s translation is smooth and nimble; it’s a page turner, for sure, and if it seems like I’ve been a bit rough on it in this paragraph in particular, I should be clear: I enjoyed The Singularity.”

Waiting for the Fear, Oğuz Atay; trans. Ralph Hubbell

A book of cramped, anxious stories. Atay, via Hubbell’s sticky translation, creates little worlds that seem a few reverberations off from reality. These are the kind of stories that one enjoys being allowed to leave, even if the protagonists are doomed to remain in the text (this is a compliment). Standouts include “Man in a White Overcoat,” “The Forgotten,” and “Letter to My Father.”

Making Pictures Is How I Talk to the World, Dmitry Samarov

Magnetic Field(s), Ron Loewinsohn☆

A hypnotic, fugue-like triptych exploring crime and art as overlapping intimacies. Through a burglar, a composer, and a novelist, it frames imagining another life as a taboo act of trespass.

Body High, Jon Lindsey

A breezy drug novel that’s funny, gross, and abject but tries to do too much too quickly. The narrator, a medical-experiment subject, dreams of writing pro-wrestling scripts, but spirals even further into mania when his underage aunt enters his life and stirs some disturbing desires. Body High is at its best when at its grimiest.

Sunday, Olivier Schrauwen☆

An achievement for slackers the world over. Sunday is a true graphic novel, by which I mean a real novel. Maybe I’ll get to a proper review of it; maybe The Comics Journal will ask me to come back to write reviews again. Anyway. Great stuff, a real achievement to those of us willing to drink a few beers before noon and fail to open the door when neighbors ring the bell.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, John le Carré☉☆

Perfect book.

Breaking and Entering, Joy Williams☆

Joy Williams’ fourth novel, 1988’s Breaking and Entering zigs when you expect it to zag. It ends up in a place no reader would expect, and I don’t mean that there’s some weird twist. It twists weirdly like life. The sentences are excellent, but so are the paragraphs. Breaking and Entering is very, very Florida, crammed with weirdos and tragedies, farcical, ironic, and thickly sauced in the laugh-cry flavor. I’m not sure exactly where it’s set, but I do know that I do know the general area, the barrier islands, skinny shining strips of weird between the Gulf and the Tampa Bay.

Hyperion, Dan Simmons

The Fall of Hyperion, Dan Simmons

I listened to Simmons’ mass-cult favorites as audiobooks—Hyperion was good; Fall was pretty terrible! But seriously, the first one is a nice postmodernist sci-fi take on Canterbury Tales.

Three Trapped Tigers, G. Cabrera Infante; trans. Donald Gardner and Suzanne Jill Levine with collaboration by Infante☆

Language! Language! Language! Bombastic, bullying, buzzing, braying, bristling— Infante’s dizzying mosaic of the fifties at night (and some hungover mornings) in Havana boxes you on your ear before kissing it, your ear, nipping the lobe even, showing off some neat tricks and other twisters of its fat vibrant tongue. A delight.

The Rest Is Silence, Augusto Monterroso; trans. Aaron Kerner

A quick clever slim novel that riffs on literary failure. A nugget from the so-called Latin Boom that surely (don’t call me Shirley!) influenced Roberto Bolaño.

The Obscene Bird of Night, José Donoso; trans. Hardie St. Martin, Leonard Mades, Megan McDowell☆

Heavy and gross, twisted and twisting, I loved Donoso’s The Obscene Bird of Night–reminded me of Goya’s Caprichos and William Faulkner and Anna Kavan soaked in Salò and Aleksei German’s adaptation of Hard to Be a God. About half way through I realized I needed to go back and put together some of the plot strands I’d missed; I think this novel is more coherent than its surreal and grotesque flourishes initially suggest.

“Presents”

by

Donald Barthelme

In the middle of a forest. Parked there is a handsome 1932 Ford, its left rear door open. Two young women are pausing, about to step into the car. Each has one foot on the running board. Both are naked. They have their arms around each other’s waist in sisterly embrace. The woman on the left is dark, the one on the right fair. Their white, graceful backs are in sharp contrast to the shiny black of the Ford. The woman on the right has turned her head to hear something her companion is saying.

At a dinner party. The eight guests are seated, in shining white plastic shells mounted on steel pedestals, in a luxurious kitchen. They sit around a long table of polished rosewood, at one end of which there is a wicker basket filled with fruit, pineapples, bananas, pears, and at the other a wicker basket containing loaves of burnt-orange bread. The kitchen floor is polished black tile; electric ovens with bronze fronts are set into the polished off-white walls. On thick glass shelves above the diners, handsome pots with herbs, jams, jellies, and tall glass jars with half-a-dozen varieties of raw pasta. Six of the guests, men and women, are conventionally clothed. The two young women (one dark, one fair) are naked, smoking cigarillos. One of them unfolds a large white linen napkin and smoothes it over her companion’s lap.

Ten o’clock in the morning. Marble, more marble, together with walnut paneling, a terrazzo floor, on the left a long (sixty feet) black-topped counter behind which the tellers sit, on the right a beige-carpeted area with three rows (three times three) of bank officers, suited and gowned. At the back, the great vault door open, functionary seated at desk reading a Gothic novel. In the center, long lines of depositors channeled to the tellers by a flattened S-curve of blue velvet ropes. Uniformed guards, etc., the American flag drooping on its standard near the vault. Two young women enter. They are naked except for black masks. One is dark, one fair. They place themselves back-to-back in the center of the banking floor. The guards rush toward them, then rush away again.

A woman seated on a plain wooden chair under a canopy. She is wearing white overalls and has a pleased expression on her face. Watching her, two dogs, German shepherds, at rest. Behind the dogs, with their backs to us, a row of naked women kneeling, sitting on their heels, their buttocks perfect as eggs or O’s — OOOOOOOOOOOOO. In profile to the scene, at the far right, Henry James — his calm, accepting gaze.

Two young women wrapped as gifts. But the gift-wrapping is indistinguishable from ordinary clothing. Or there is a distinction, in that what they are wearing is perhaps a shade newer, brighter, more studied than ordinary clothing, proclaims the specialness of what is wrapped, argues for immediate unwrapping, or if not that, unwrapping at leisure, with wine, cheese, sour cream.

Two young women, naked, tied together by a long red thread. One is dark, one is fair.

Large (eight by ten feet) sheets of white paper on the floor, six or eight of them. The total area covered is perhaps 200 feet square; some of the sheets overlap. A string quartet is playing at one edge of this area, and irregular rows of handsomely-dressed spectators border another. A large bucket of blue paint sits on the paper. Two young women, naked. Each has her hair rolled up in a bun; each has been splashed, breasts, belly, and thighs, with blue paint. One, on her belly, is being dragged across the paper by the other, who is standing, gripping the first woman’s wrists. Their backs are not painted. Or not painted with. The artist is Yves Klein.

Two young men, wrapped as gifts. They have wrapped themselves carefully, tight pants, open-throated shirts, shoes with stacked heels, gold jewelry on right and left wrists, codpieces stuffed with credit cards. They stand, under a Christmas tree big as an office building, the women rush toward them. Or they stand, under a Christmas tree big as an office building, and no women rush toward them. A voice singing inappropriate Easter songs, hallelujahs.

Two young men, artists, naked in a loft on Broome Street, are painting a joint portrait of four young women, fully clothed, who are standing in a row with their backs to the artists, who are sipping coffee from paper cups (the paper cup held in the left hand, the brush or palette knife in the right) and carefully regarding the backs of the women, who from time to time let slip from the sides of their mouths comments (encouraging or disparaging) about the artists, who for their part are not intimidated by these comments which have mostly to do with the weather and future projects but in some cases with the comparative beauty and masculinity (because of course the women have opinions about these matters, expressed in whispers just loud enough to be overheard) of the naked artists, who are mostly worried about the stamina and comfort (four or five hours’ work yet ahead) of the women, who are feeling rather hot and peevish in the white-painted, rather stuffy (although the big windows have been opened) loft of the artists, who are perfectly comfortable themselves, being naked, but do recognize the fact that some discomfort may be engendered by the heavy overcoats worn by the women, who are in truth pulling and tugging irritably upon these gross garments, increasing the nervousness of the artists, who are also concerned about the effect the scene might have upon someone who just blundered into it, such as the four lovers of the women, who are thinking now (by coincidence) of those selfsame lovers, Luke, Matt, John, and Mark, and what they might say if, battered by the heat of the hot sun, they staggered into an air-conditioned art gallery and there beheld a sixteen-by-forty foot painting of four backs, backs that they know intimately even through the layers of clothes, and begin to wonder whether the clothes on those backs had just been painted on (but of course they had been painted on, like everything else on the canvas) but had been really there while the women were posing for the naked artists, who are as character types notoriously . . .

Nowhere — the middle of it, its exact center. Standing there, a telephone booth, green with tarnished aluminum, the word PHONE and the system’s symbol (bell in ring) in medium blue. Inside the telephone booth, two young women, one dark, one fair, facing each other. Their breasts and thighs brush lightly (one holding the receiver to the other’s ear) as they place phone calls to their mothers in California and Maine. In profile to the scene, at far right, Henry James, wearing white overalls.

Henry James, wearing white overalls (Iron Boy brand) is attending a film. On the screen two young women, naked, are playing ping-pong. One makes a swipe with her paddle at a ball the other has placed just over the net and misses, bruising her right leg. The other puts down her paddle and walks around the table (gracefully) to examine the bruise; she places her hands on either side of the raw, ugly mark, then bends to kiss it. Henry James picks up his hat and walks thoughtfully from the theatre. Behind the popcorn machine in the lobby stand two young women, naked, one dark and one fair. Henry James approaches the popcorn stand and purchases, for 35¢, a bag of M & Ms. He opens the bag with his teeth. The women smile at each other.

Two young women wearing web belts to which canteens are attached, nothing more, marching down Broadway again. They are followed by a large crowd, bands, etc.

A plaza or open space. Two young women on their hands and knees. They are separated by a distance of eight feet, both facing in the same direction. Rough wooden boards (one by tens) have been laid across their backs to form a sort of table. On top of the table are piled bags and bags of M & Ms, hundreds of bags some of which have been opened spilling the chocolate out onto the table. A small army of insects, not ants but other chocolate-loving insects, informed of this prime target by scouts, is advancing across the plaza toward the rear of the table. The vanguard (the insects are a half-inch long and, closely inspected, resemble tiny black toothbrushes) reaches the left leg of the young woman on the left side of the table. The boldest members leap upon the leg, a line of insects runs up the leg toward the cleft of the buttocks. The table shudders and collapses.

The world of work. Two young women, one dark, one fair, wearing web belts to which canteens are attached, nothing more. They are sitting side-by-side on high stools (OO OO) before a pair of draughting tables, inking-in pencil drawings. Or, in a lumberyard in Southern Illinois, they are unloading a railroad car containing several hundred thousand board feet of Southern yellow pine. Or, in the composing room of a medium-sized Akron daily, they are passing long pieces of paper through a machine which deposits a thin coating of wax on the back side, and then positioning the type on a page. Or, they are driving two Yellow cabs which are racing side-by-side up Park Avenue with frightened passengers, each driver trying to beat the other to a hole in the traffic in front of them. Or, they are seated at adjacent desks in the beige-carpeted area set apart for officers in a bank (possibly the very same bank they had entered, naked, masked, several days ago), refusing loans. Or, they are standing bent over, hands on knees, peering into the site of an archaeological dig in the Cameroons. Or, they are teaching, in adjacent classrooms, Naked Physics — in the classroom on the left, Naked Physics I, and in the classroom on the right, Naked Physics II. These courses are very popular. Or, they are kneeling, sitting on their heels, before a pair of shoeshine sta

nds, polishing the expensive boots, suave loafers, of their admiring customers. OO OO.

Two women, one dark and one fair, wearing parkas, blue wool watch caps on their heads, inspecting a row of naked satyrs, hairy-legged, split-footed, tailed and tufted, who hang on hooks in a meat locker where the temperature is a constant 18 degrees. The women are tickling the satyrs under the tail, where they are most vulnerable, with their long white (nimble) fingers tipped with long curved scarlet nails. The satyrs squirm and dance under this treatment, hanging from hooks, while other women, seated in red plush armchairs, in the meat locker, applaud, or scold, or hug and kiss, in the meat locker.

Two women, one dark and one fair, wearing parkas, blue wool watch caps on their heads, inspecting a row of naked young men, hairy-legged, many-toed, pale and shivering, who hang on hooks in a meat locker where the temperature is a constant 18 degrees. The women are tickling the young men under the tail, where they are most vulnerable, with their long white (nimble) fingers tipped with long curved scarlet nails. The young men squirm and dance under this treatment, hanging from hooks, while giant eggs, seated in red plush chairs, boil.

Two young women, naked, trundle the giant boiled eggs to market in wheelbarrows. They move through double rows of shouting civilians who applaud the size, whiteness, and exquisite shape of the eggs, and the humor and good cheer of the women. The grandest eggs ever seen in this part of the country, and the most gloriously-powered wheelbarrows! There is no end to the intoxicating noise. The women are sweating, moisture visible on their backs, on their legs and breasts, on their white, beautifully-formed shoulders. Yet they smile, and smile, and smile, their hands on the handles of the wheelbarrows, their sturdy sweating backs bent into the work. Like Henry James writing a novel, they trundle onward, placing one foot in front of the other in sweet, determined, dogged bliss — the achievement of a task.

Bliss: A condition of extreme happiness, euphoria. The nakedness of young women, especially in pairs (that is to say, a plenitude) often produces bliss in the eye of the beholder, male or female. If you have an elbow in your mouth, then you are occupied, for the moment, but your mind often wanders away, toward more bliss, wondering if you should be doing something else, with your arms and legs, so as to provide more static along the surface of the situation, wherein the two (naked) young women lie unfolded before you, waiting for you to fold them up again in new, interesting ways. Oh they are good kids, no doubt about it, and brave and forthright too, and mind their manners and their eggs, and have hope and ambitions, and are supportive and giving as well as chilly and austere — most of all, naked. That is a delight, let us confess the fact, and that is why we are considering all these different ways in which naked young women may be conceptualized, in the privacy of our studies, dealt out like cards from a deck of thin, flexible, six-foot-tall mirrors. Doubtless women do the same sort of thing in regard to us, in the privacy of their studies, or even better things, things we have not yet been able to imagine, or possibly nothing at all — maybe they just sit there, the beauty of a naked thumb, for example, or a passionate, interestingly-historied wrist. What if they don’t care? If this is the case, send them to the elephants, let them sit around all day listening to the elephants cry “Long live King Babar! Long live Queen Celeste!” Few naked young women can take much of this.

Back to business: Two naked young women are walking, with an older man in a white suit, on a plain in British Columbia. The older man has told them that he is Henry James, returned to earth in a special dispensation accorded those whose works, in life, have added to the gaiety of nations. They do not quite believe him, yet he is stately, courteous, beautifully-spoken, full of anecdotes having to do with the upper levels of London society. One of the naked young women reaches across the chest of Henry James to pinch, lightly, the rosy, full breast of the second young woman, who —

I usually finish reading a novel if I stick with it for, say thirty-to-fifty pages. However, as is the case with many readers, I suspect, very long novels foil me; or, rather, time foils me. Obligations intercede. Here are some long novels that I had to put aside for another time. From the top:

Lies and Sorcery, Elsa Morante (775 pages)

If the bookmark I left in Jenny McPhee’s translation Lies and Sorcery is not lying (or ensorcelled), I got seventy pages into it before getting sidetracked with something else. I remember liking what I was reading but also that the book seemed very heavy over my head at night.

The Strudlhof Steps, Heimito von Doderer (840 pages)

I’ve really enjoyed the first fifty pages of Heimito von Doderer’s The Strudlhof Steps (in translation by Vincent Kling). I’ve enjoyed them so much that I’ve read them at least four times over the past three years. The longest I’ve waded into the Steps was to page 99. Again, a slimmer model comes round and I lose my focus—but of the four novels I’ve listed here, von Doderer’s is the one that’s made the biggest impression on me. My bites may have been shallow but I keep going in for seconds.

A Bended Circuity, Robert S. Stickley (637 pages)

Although it’s the shortest novel on this list, my edition of RSS’s ABC feels cramped and constrained. I think the novel would like a bigger home. The pages are too bright, the font too small, the margins too narrow. It’s a cramped reading experience. I suppose I could break down and buy the Corona\Samizdat edition, which may be easier to ease into. Or an e-book? RSS, please agree to an e-book! Some of us have aging eyes. Oh, I got to page 48.

Miss MacIntosh, My Darling, Marguerite Young (1321 pages)

I cracked into Marguerite Young’s Miss MacIntosh, My Darling twice this year; once in the Spring and once in the Fall. Maybe I’ll try again in the Winter. I stalled out 78 pages in, at the end of chapter 3.