☉ indicates a reread.

☆ indicates an outstanding read.

In some cases, I’ve self-plagiarized some descriptions and evaluations from my social media and blog posts.

I have not included books that I did not finish or abandoned.

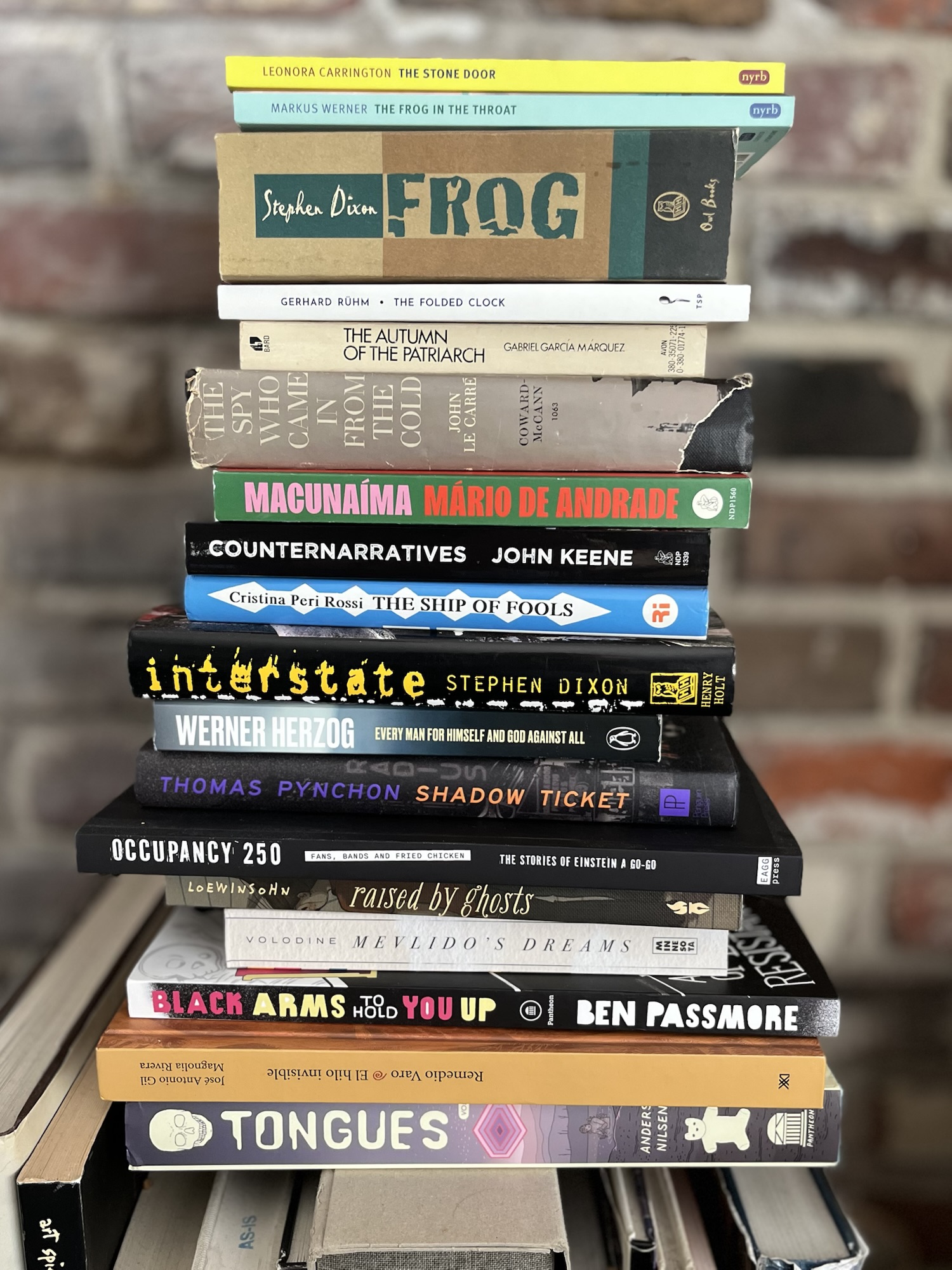

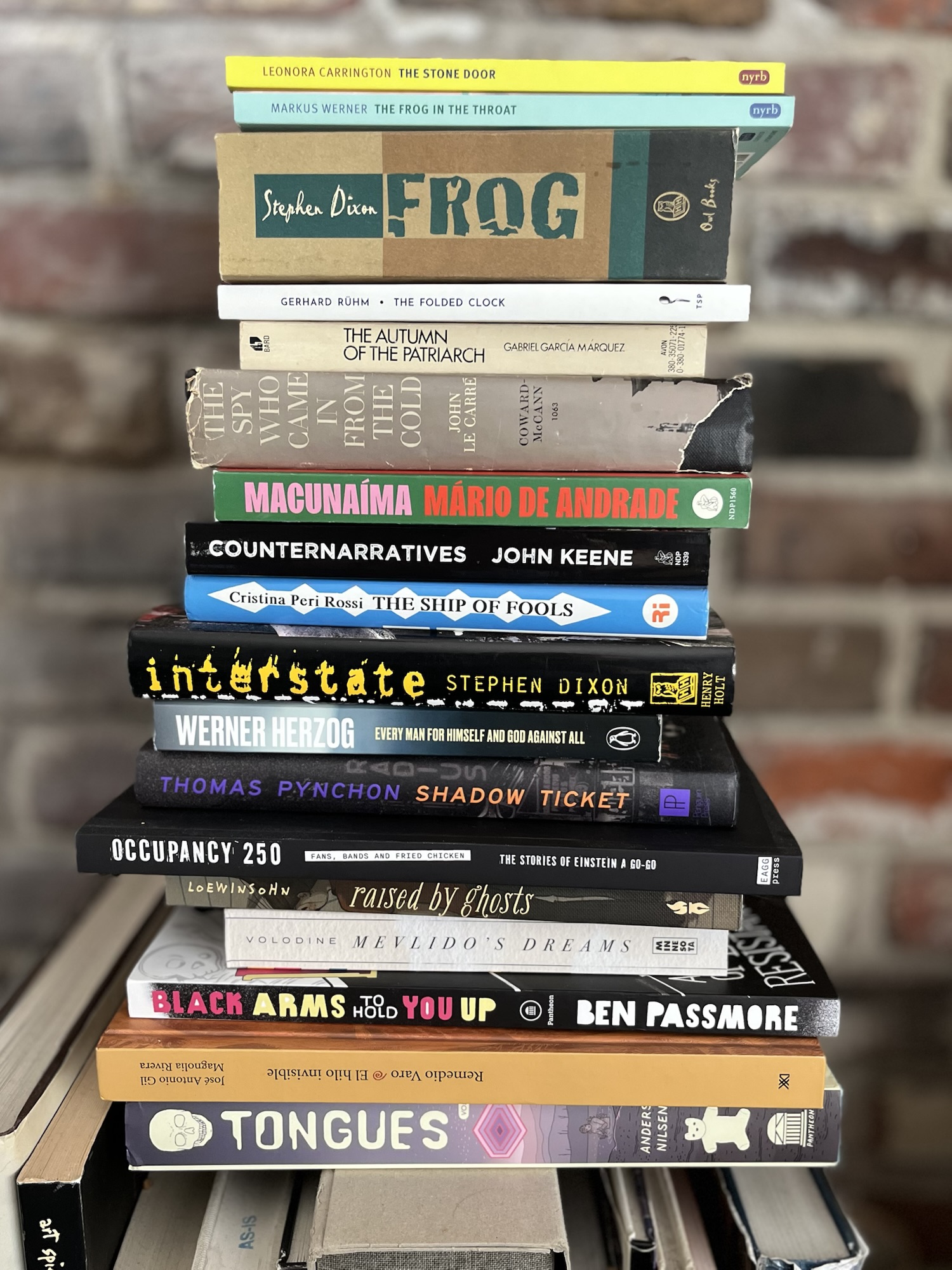

Every Man for Himself and God Against All, Werner Herzog☆

I got a paperback copy of Herzog’s memoir for Christmas last year but ended up listening to him read the audiobook on my commute for a week or two. Every Man for Himself was one of four memoirs as-read-by-the-author I listened to this year. The other three: The Friedkin Connection by William Friedkin; The Harder I Fight the More I Love You by Neko Case; Rumors of My Demise by Evan Dando. I enjoyed all four memoirs and maybe as I go through this post I’ll pull a few common threads. Herzog’s memoir is bonkers, better than fiction. It really is one of those deals where a paragraph starts one way and a few sentences later you’re in a totally different place.

Dispatches from the District Committee, Vladimir Sorokov (translation by Max Lawton; illustrations by Gregory Klassen)

An absolutely vile book. I loved it.

Raised by Ghosts, Briana Loewinsohn

Loewinsohn’s love letter to the latchkey nineties hit me hard. I reviewed it here.

Nazi Literature in the Americas, Roberto Bolaño (translation by Chris Andrews)☉

I think I was trying to get through the beginning of a novel by an “alt” midlist author when I realized I’d rather read something I loved. Or maybe there was something else in the air in late January. The notes on the draft for this post are cryptic.

Feminine Wiles, Jane Bowles

A slim lil guy, a nice reprieve from current events in January, a reminder that sanity is precarious.

Interstate, Stephen Dixon☆

From my review: “It upset me deeply, reading Stephen Dixon’s 1995 novel Interstate. It fucked me up a little bit, and then a little bit more, addicted to reading it as I was over two weeks in a new year.”

Remedios Varo: El hilo invisible, Jose Antonio Gil and Magnolia Rivera

A lot of Varo’s pictures, but also a lot of Spanish. I was trying hard at the time (to read Spanish). I used my iPhone to translate a lot.

Borgia, Alejandro Jodorowsky and Milo Manara

Indian Summer, Milo Manara and Hugo Platt

Caravaggio, Milo Manara

A nice little run there, I seem to recall. Borgia was the best.

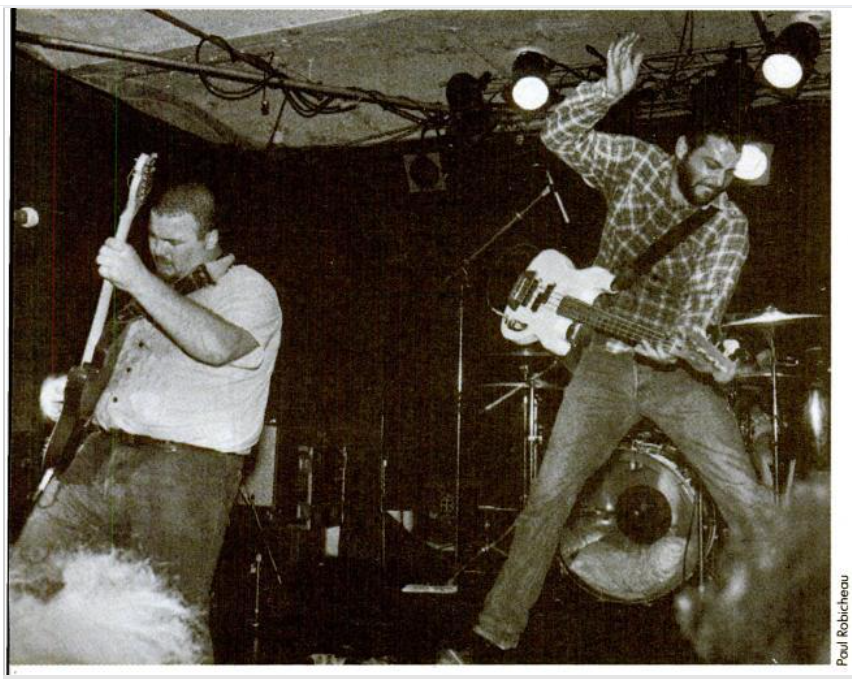

Occupancy 250: The Stories of Einstein A Go-Go

The Einstein A Go-Go was an all-ages music club at Jacksonville Beach that was a massive part of my teenage years. I saw so many amazing bands there over four or five years (including Luna, Thinking Fellers Union Local 282, Man or Astroman, Sebadoh, Polvo, Superchunk, Archers of Loaf, and so many more), met so many cool people, and even played there with my band a time or two or five. And if I was too late (that is, too young) to see acts like Nirvana, The Replacements, 10,000 Maniacs, The Cranberries, and Soundgarden there at the the end of the eighties and beginning of the nineties, it feels pretty swell to see my band’s name on the back of Occupancy 250 right there in the mix, as well as flyers and photos. Occupancy 250 is like the yearbook we never got when the club had to shut its doors in ’97 in the name of beachfront development. What a gift it was. A few months ago we went to a reunion event, featuring bands like The Cadets and Emperor X. I’ve never been to a high school reunion, but I know that this was better.

Autumn of the Patriarch, Gabriel García Márquez (translation by Gregory Rabassa)☆

Loved it. A discussion with a colleague after, a Spanish instructor, led to my reading Cela, Peri Rossi, and Rulfo.

The Hive, Camilo José Cela (translation by Anthony Kerrigan)

Pascual Duarte, Camilo José Cela (translation by Anthony Kerrigan)

I liked them both but liked Pascal Duarte more than La colmena. I would love to read Cela’s 1988 novel Cristo versus Arizona if I could get my pink little hands on an English-language copy.

The Friedkin Connection, William Friedkin☆

I think that Spotfiy suggested that I listen to Friedkin’s memoir after I finished the Herzog memory; in any case, there was a lot of overlap. Like Herzog, Friedkin had no idea how to make a film and never really developed a baseline beyond, Doing the thing for real and filming it, whatever the thing was. Going to make a film where a criminal is going to counterfeit US currency? Better teach Willem Dafoe how to, I don’t know, counterfeit money and just film that instead of, like, getting a props department involved. (Weird overlap: both Friedkin and Herzog laud Michael Shannon as the greatest actor of his generation.)

I loved this memoir. It starts, if I recall correctly, with Friedkin admitting that he threw away a sketch by Basquiat and an offer from Prince. It ends with Friedkin telling his wife, legendary producer Sherry Lansing, to pass on Forrest Gump. Amazing stuff.

The Ship of Fools, Cristina Peri Rossi (translation by Psiche Hughes)☆

I loved it.

Monsieur Teste, Paul Valéry (translation by Charlotte Mandell)

I hated it.

Pedro Páramo, Juan Rulfo (translation by Douglas J. Weatherford

I liked it!

Blood Meridian, Cormac McCarthy☉

I guess I fall into rereading this all the time.

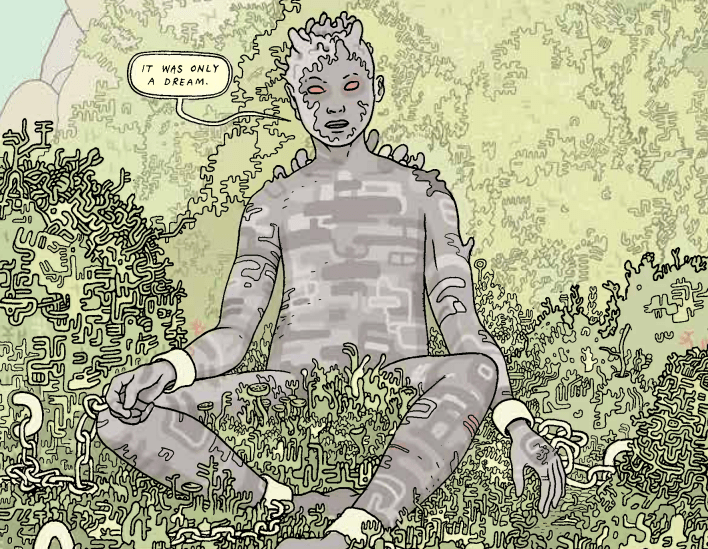

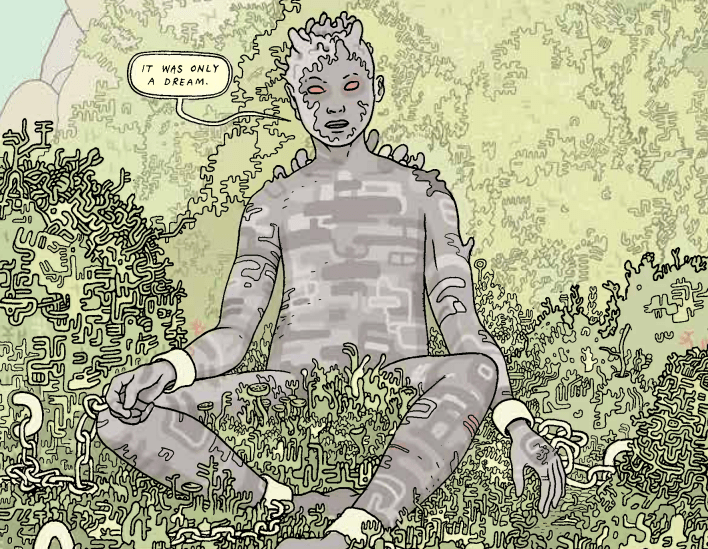

Tongues, Anders Nilsen☆

Amazing stuff.

Day of the Triffids, John Wyndham

I probably would’ve read Day of the Triffids a dozen times as a kid instead of, like, Joan D. Vinge’s novelization of Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome, if there had been a copy in the lending library in Tabubil. Anyway, I’m glad I got to it when I did.

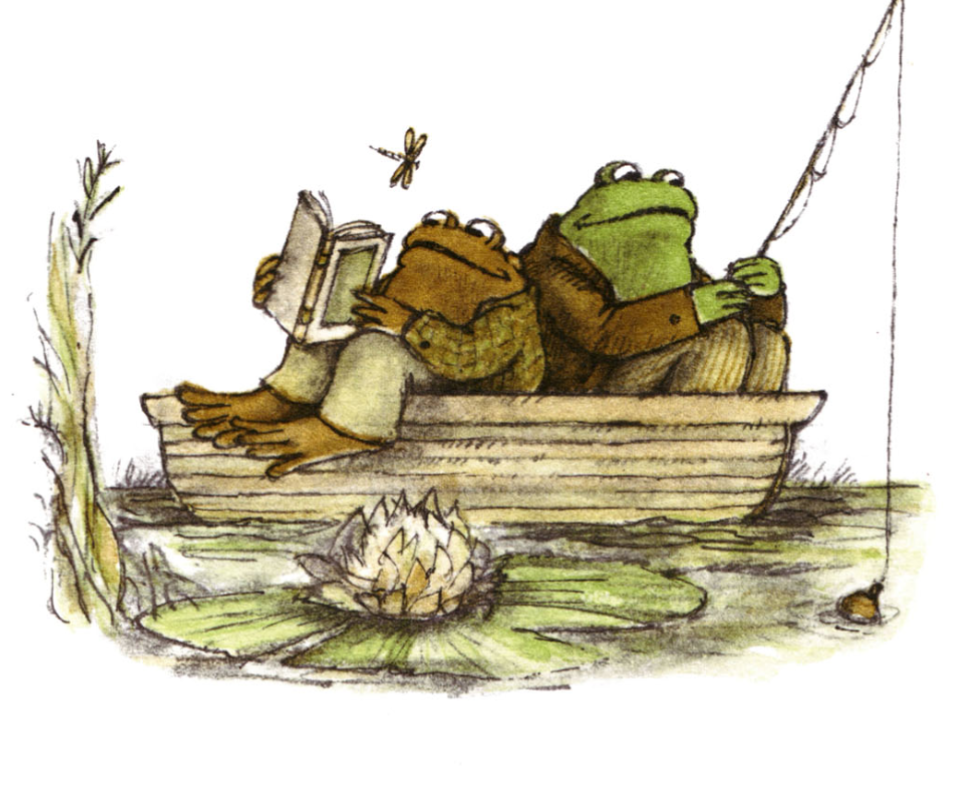

Frog, Stephen Dixon☆

Above, I wrote I have not included books that I did not finish or abandoned; look, I didn’t finish Frog, but in some ways it’s the most important book — or rather, most important, reading experience — for me this year.

An old great friend mailed me his copy back in March. I read and loved a hefty chunk of Frog, a long book, but abandoned it when another great old friend died unexpectedly in early May. I was deep into it but there was no comfort in it, in Frog.

And so then well I just read or reread a bunch of John le Carré novels.

Call for the Dead, John le Carré

A Murder of Quality, John le Carré☆

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, John le Carré

The Looking Glass War, John le Carré

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, John le Carré☉☆

Was a blur, thank you to Mr. Le Carré’s ghost. A Murder of Quality was my favorite (I think). (I was a fucking mess and these books really helped me.)

The Woman with Fifty Faces: Maria Lani and the Greatest Art Heist That Never Was, by Jon Lackman and Zack Pinson.☆

I read it all in one sitting. Loved it.

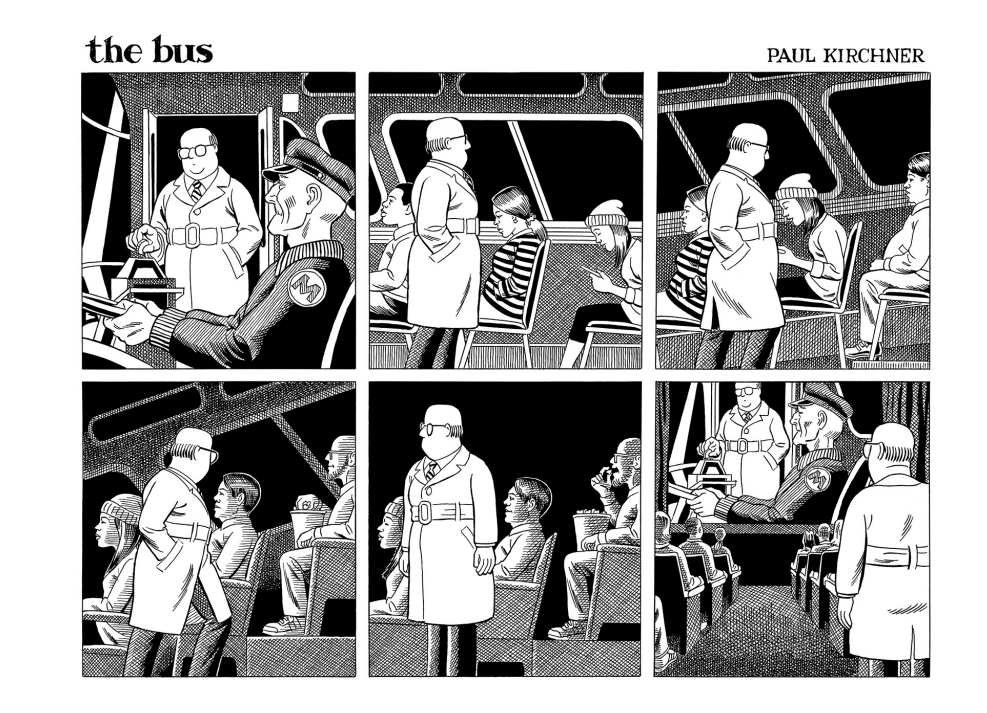

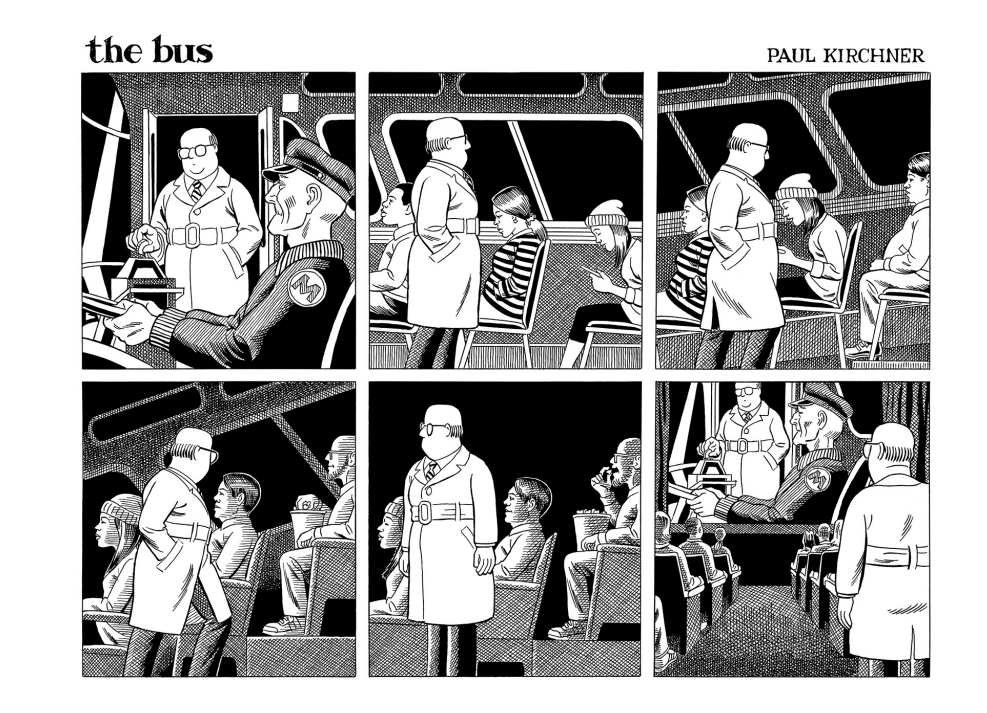

The Bus 3, Paul Kirchner

I reviewed it here.

Portalmania, Debbie Urbanski

In my review, I wrote that, “Debbie Urbanski’s new collection Portalmania is a metatextual tangle of science fiction, fantasy, and horror where portals don’t offer escape so much as expose the fractures beneath family, love, and identity.”

Dreamsnake, Voya McIntrye

I liked it!

The Stone Door, Leonore Carrington

Wrestled with this dude a lot and it beat me. I thought it would twist one way and it did another thing. Ended up reading it twice in the summer and I guess I’ll read it again.

The Great Mortality, John Kelly

Kelly’s Black Death chronicle was a comfort read this summer.

Figures Crossing the Field Towards the Group, Rebecca Grandsen

Skip my review of Grandsen’ poetic post-apocalyptic miniature epic and just buy it and read it.

Macunaíma, Mário de Andrade (translation by Katrina Dodson)☆

I am so glad my guy at the bookstore sold me on this one. A synthesis of Brazilian folklore with high and low modernism (eh, Modernism?).

The Sense of an Ending, Julian Barnes

A corny book a colleague recommended. I’m happy that someone I know IRL wants me to read a book and talk about it with them.

Unkempt Thoughts, translation by Jacek Galazka (translation by Jacek Galazka)

More Unkempt Thoughts Stanislaw J. Lec (translation by Jacek Galazka)

Aphorisms.

The Frog in the Throat, Markus Werner (translation by Michael Hofmann)☆

I gave the guy who gave me the Julian Barnes this novel; he didn’t like it!

I loved it. In my review of The Frog in the Throat. I noted that “you could throw a small dart in this short book and find a nice line” its protagonist. I included a lot of those pithy gems in the review if you want a sample.

Counternarratives, John Keene☆

Amazing stuff. I was halfway through when I realized that Keene wrote the intro to my edition of Mário de Andrade’s Macunaíma. My favorite piece in the collection reads like a riff on Melville’s Benito Cereno with strong Gothic undertones.

Mevlido’s Dreams, Antoine Volodine (translation by Gina M. Stamm)☆

A bleak, dystopian noir novel set several centuries in a ruined city-state wherein Mevlido’s fragmented consciousness becomes a vessel for Volodine’s haunting post-exotic vision of history, language, and apocalypse. Loved it! My review.

Shadow Ticket, Thomas Pynchon☆

The highlight of 2025 in reading was a new late Pynchon novel. It might not have been the best novel I read this year, but it was my favorite reading experience. I ended up reading it twice, running a series of posts I called Notes on Thomas Pynchon’s novel Shadow Ticket. At the end of those notes, I wrote:

“I should probably distill my thoughts on Shadow Ticket into a compact, “proper” review, but I’ve sat with the novel now for two months, reading it twice, and really, really enjoying it. I never expected to get another Pynchon novel; it’s a gift. I loved its goofy Gothicism; I loved its noir-as-red-herring-genre-swap conceit; I loved even its worst puns (even “sofa so good”). I loved that Pynchon loves these characters, even the ones he might not have had the time or energy to fully flesh out — this is a book that, breezy as it reads, feels like a denser, thicker affair. And even if he gives us doom on the horizon in the impending horrors of genocide and atomic death, Pynchon ends with the hopeful image of two kids chasing sunsets. Great stuff.”

Black Arms to Hold You Up, Ben Passmore

Sports Is Hell, Ben Passmore

Subtitled A History of Black Resistance, Passmore’s comic is more fun than you would think a book about fighting a racist state should be. I still owe it a proper review. It made me go back and read Passmore’s Sports Is Hell, which is kinda like the NFL x Walter Hill’s The Warriors x George Herriman’s Krazy Kat.

The Harder I Fight the More I Love You, Neko Case

Of the four memoirs I listened to this year, musician Neko Case’s is the most artfully written, packing in bursts of sensory images that pivot cannily to evoke very specific memories that connect the reader to the storyteller. The memoir is heavy on Case’s childhood and adolescence and purposefully avoids a direct accounting of her musical career. That’s not to say there isn’t a lot about music in here — there is (life on the road, songwriting, a nice section on her tenor guitar) — but Case seems to avoid going into too much detail about interpersonal relationships with other musicians. She also seems to want to apologize for some past behaviors, but the apologetic language is indirect and even cagey (Evan Dando’s memoir is a massive contrast here — the dude dishes deep, but is also frank and clear and specific about all the bad mean shit he did to people when he was younger).

Neko Case’s magnificent singing voice translates well to reading her memoir. She’s really good at reading it — expressive without being hammy, subtle, artful. I would love to hear her read other audiobooks, but I’m also happy for her to keep her focus on making music and playing live.

The King in Yellow, Robert Chambers☉

I played this silly fun indie game called The Baby in Yellow which led me to reread The King in the Yellow for the first time since I went nuts over True Detective (the first season). The first two stories were much stronger than I remembered — much weirder.

Acid Temple Ball, Mary Sativa

A Satyr’s Romance, Barry N. Malzberg

Flesh and Blood, Anna Winter

I spent some of the year browsing through a copy of the Maurice Girodias edited volume The Olympia Reader. That edition offers excerpts from Olympia Press’s more “respectable” authors, like William Burroughs, Chester Himes, Henry Miller, Jean Genet etc. I downloaded a bunch of trashier Olympia titles and ended up reading these three. They were all pretty bad but also fun. Acid Temple Ball is like a sex-positive Go Ask Alice; both A Satyr’s Romance and Flesh and Blood are well-beyond “problematic” in their depictions of sexual relationships.

The Pisstown Chaos, David Ohle☆

In my golden-hued review, I called The Pisstown Chaos “a foul, abject, hilarious, zany vaudeville act, a satire of post-apocalyptic literature, an extended riff on American hucksterism. It’s very funny and will make most readers queasy.”

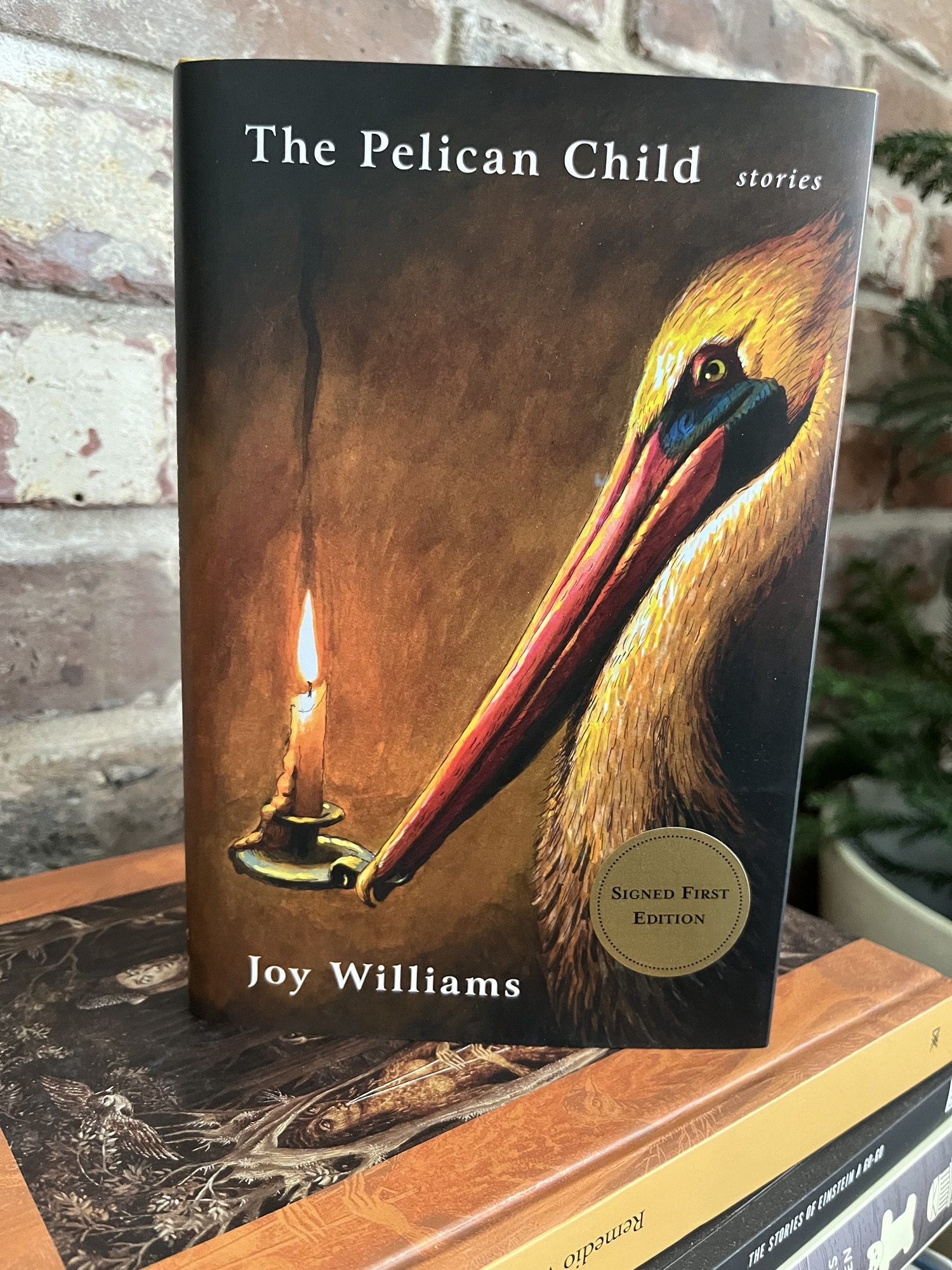

The Changeling, Joy Williams

Joy Williams is one of my favorite writers, but I’ll admit I was disappointed in her second novel, 1978’s The Changeling. I loved how dark and weird and oppressive it was, but soon tired of spending time in the rattled consciousness of its alcoholic hero, Pearl. When Williams explores beyond Pearl, the novel hints at weird Gothic cult island shit that is super-intriguing — but we always have to retreat back to our depressed, insane hero.

The Folded Clock, Gerhard Rühm (translation by Alexander Booth)

A collection of “number poems, comprising typewriter ideograms, typed concrete poetry, collages of everyday paper ephemera and scraps, and a wide variety of literary forms where the visual pattern created on the page underpins the thematic meaning,” as publisher Twisted Spoon puts it. A fascinating and frustrating read that hearkens back to the good ole days of the avant garde.

Rumors of My Demise, Evan Dando

In a review at the Guardian of Evan Dando’s memoir Rumors of My Demise, Alexis Petridis writes that the Lemonheads leader “sounds insufferable, but weirdly, he doesn’t come across that way.” Dando doesn’t try to deny, deflect, or otherwise shade his life. He’s upfront about his privileged background, his good looks, and his love of the rock star lifestyle. He’s also, as he always was, very upfront about the drugs. I was in eighth grade when It’s a Shame about Ray came out. I loved it. I loved the follow up album, Come on Feel the Lemonheads even more. I am, I suppose, the target audience for this book, and I found it very satisfying. I also think listening to Dando read it is really remarkable. He’s charming and affable, but he doesn’t seem comfortable reading out loud (you can hear it, for example, in an awkward pause when he has to change the page during the middle of a sentence). It’s also remarkably honest, and culminates in a series of apologies to many of the people he’d hurt when he was younger (“If I could go back in time and give a bit of advice to myself, I’d say ‘Evan, don’t be such a dick.’”)

My best friend Nick, who died this May, was a bigger Lemonheads fan than I was. I think he would have loved Rumors of My Demise and I thought about him all the time while I was listening to it, wanting to text him, Hey, you’re gonna love this story about Dando drinking Fanta Orange and Absolut with Keith Richards or, Man, Dando really has a score to settle with Courtney Love, or Dando’s some kind of disaster magnet — he lived right by the Twin Towers and was home on 9/11, he was in L.A. during the King riots, in Paris when Diana died, on Martha’s Vineyard when JFK Jr. crashed…or, Man, Dando seems to have finally quit heroin, good for him. I didn’t get to text those things so I’m writing them here.

Happy New Year to you and yours.