“The Three Castles”

an Italian folktale retold by Italo Calvino

translated by George Martin

A boy had taken it into his head to go out and steal. He also told his mother.

“Aren’t you ashamed!” said his mother. “Go to confession at once, and you’ll see what the priest has to say to you.”

The boy went to confession. “Stealing is a sin,” said the priest, “unless you steal from thieves.”

The boy went to the woods and found thieves. He knocked at their door and got himself hired as a servant.

“We steal,” explained the thieves, “but we’re not committing a sin, because we rob the tax collectors.”

One night when the thieves had gone out to rob a tax collector, the boy led the best mule out of the stable, loaded it with gold pieces, and fled.

He took the gold to his mother, then went to town to look for work. In that town was a king who had a hundred sheep, but no one wanted to be his shepherd. The boy volunteered, and the king said, “Look, there are the hundred sheep. Take them out tomorrow morning to the meadow, but don’t cross the brook, because they would be eaten by a serpent on the other side. If you come back with none missing, I’ll reward you. Fail to bring them all back, and I’ll dismiss you on the spot, unless the serpent has already devoured you too.”

To reach the meadow, he had to walk by the king’s windows, where the king’s daughter happened to be standing. She saw the boy, liked his looks, and threw him a cake. He caught it and carried it along to eat in the meadow. On reaching the meadow, he saw a white stone in the grass and said, “I’ll sit down now and eat the cake from the king’s daughter.” But the stone happened to be on the other side of the brook. The shepherd paid no attention and jumped across the brook, with the sheep all following him.

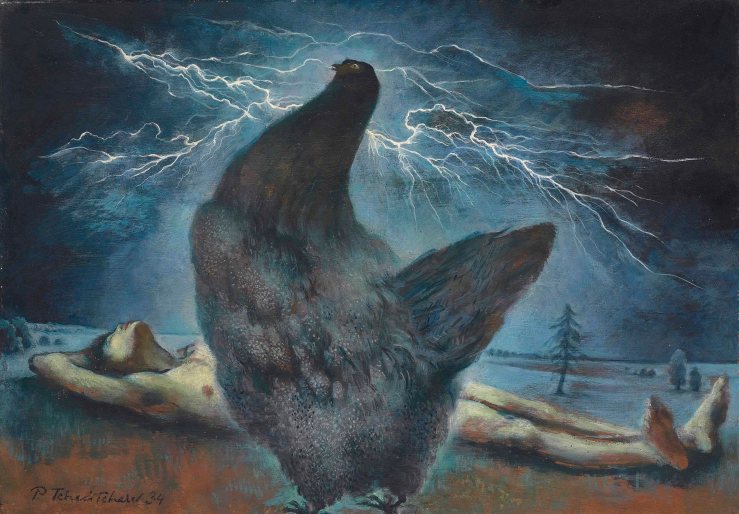

The grass was high there, and the sheep grazed peacefully, while he sat on the stone eating his cake. All of a sudden he felt a blow under the rock which seemed to shake the world itself. The boy looked all around but, seeing nothing, went on eating his cake. Another blow more powerful than the first followed, but the shepherd ignored it. There was a third blow, and out from under the rock crawled a serpent with three heads. In each of its mouths it held a rose and crawled toward the boy, as though it wanted to offer him the roses. He was about to take them, when the serpent lunged at him with its three mouths all set to gobble him up in three bites. But the little shepherd proved the quicker, clubbing it with his staff over one head and the next and the next until the serpent lay dead.

Then he cut off the three heads with a sickle, putting two of them into his hunting jacket and crushing one to see what was inside. What should he find but a crystal key. The boy raised the stone and saw a door. Slipping the key into the lock and turning it, he found himself inside a splendid palace of solid crystal. Through all the doors came servants of crystal. “Go

od day, my lord, what are your wishes?”

“I wish to be shown all my treasures.”

So they took him up crystal stairs into crystal towers; they showed him crystal stables with crystal horses and arms and armor of solid crystal. Then they led. him into a crystal garden down avenues of crystal trees in which crystal birds sang, past flowerbeds where crystal flowers blossomed around crystal pools. The boy picked a small bunch of flowers and stuck the bouquet in his hat. When he brought the sheep home that night, the king’s daughter was looking out the window and said, “May I have those flowers in your hat?”

“You certainly may,” said the shepherd. “They are crystal flowers culled from the crystal garden of my solid crystal castle.” He tossed her the bouquet, which she caught.

When he got back to the stone the next day, he crushed a second serpent head and found a silver key. He lifted the stone, slipped the silver key into the lock and entered a solid silver palace. Silver servants came running up saying, “Command, our lord!” They took him off to show him silver kitchens, where silver chickens roasted over silver fires, and silver gardens where silver peacocks spread their tails. The boy picked a little bunch of silver flowers and stuck them in his hat. That night he gave them to the king’s daughter when she asked for them.

The third day, he crushed the third head and found a gold key. He slipped the key into the lock and entered a solid gold palace, where his servants were gold too, from wig to boots; the beds were gold, with gold sheets, pillows, and canopy; and in the aviaries fluttered hundreds of gold birds. In a garden of gold flowerbeds and fountains with gold sprays, he picked a small bunch of gold flowers to stick in his hat and gave them to the king’s daughter that night.

Now the king announced a tournament, and the winner would have his daughter in marriage. The shepherd unlocked the door with the crystal key, entered the crystal palace and chose a crystal horse with crystal bridle and saddle, and thus rode to the tournament in crystal armor and carrying a crystal lance. He defeated all the other knights and fled without revealing who he was.

The next day he returned on a silver horse with trappings of silver, dressed in silver armor and carrying his silver lance and shield. He defeated everyone and fled, still unknown to all. The third day he returned on a gold horse, outfitted entirely in gold. He was victorious the third time as well, and the princess said, “I know who you are. You’re the man who gave me flowers of crystal, silver, and gold, from the gardens of your castles of crystal, silver, and gold.”

So they got married, and the little shepherd became king.

And all were very happy and gay,

But to me who watched they gave no thought nor pay.