Ishmael Reed’s 1974 novel The Last Days of Louisiana Red is a sharp, zany satire of US culture at the end of the twentieth century. The novel, Reed’s fourth, is a sequel of sorts to Mumbo Jumbo (1972), and features that earlier novel’s protagonist, the Neo-HooDoo ghost detective Papa LaBas.

In Mumbo Jumbo, Reed gave us the story of an uptight secret society, the Wallflower Order, and their attempt to root out and eradicate “Jes’ Grew,” a psychic virus that spreads freedom and takes its form in arts like jazz and the jitterbug. The Last Days of Louisiana Red also employs a psychic virus to drive its plot, although this transmission is far deadlier. “Louisiana Red” is a poisonous mental disease that afflicts black people in the Americas, causing them to fall into a neo-slave mentality in which they act like “Crabs in the Barrel…Each crab trying to keep the other from reaching the top.”

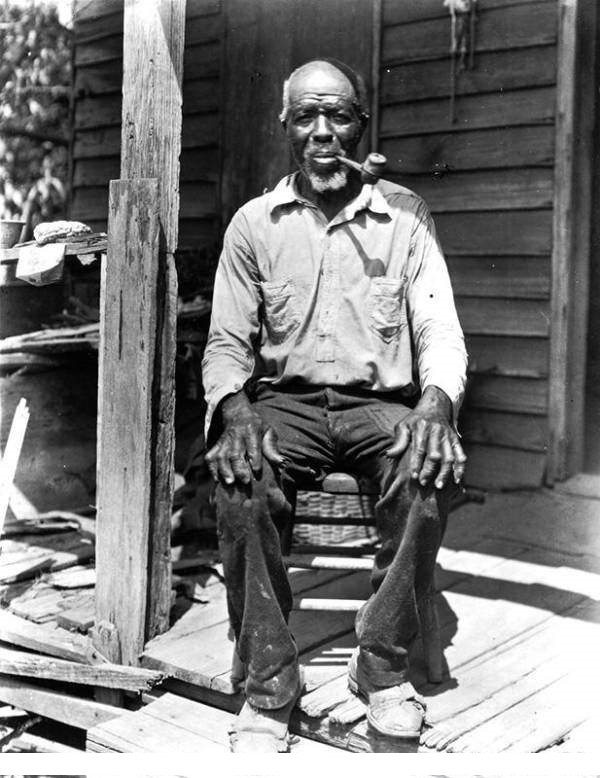

The Last Days of Louisiana Red begins with Ed Yellings, “an american negro itinerant who popped into Berkeley during the age of Nat King Cole. People looked around one day and there he was.” Yellings is the West Coast counterpart to New-York-based Papa LeBas, a fellow Worker of Neo-HooDoo who fights against the secret forces of psychic slavery.

Sliding into the mythological motif that ripple through Louisiana Red, Reed writes,

When Osiris entered Egypt, cannibalism was in vogue. He stopped men from eating men. Thousands of years later when Ed Yellings entered Berkeley, there was a plague too, but not as savage. After centuries of learning how to be subtle, the scheming beast that is man had acquired the ability to cover up.

Yellings’ mission is to destroy the psychic cannibalism that afflicts his people. He gets to it, and earns “a reputation for being not only a Worker [of the voodoo arts] but a worker too.” Yellings’ working class bona fides helps solidify his sympathies and his mission:

Since he worked with workers, he gained a knowledge of the workers’ lot. He knew that their lives were bitter. He experienced their surliness, their downtroddenness, their spitefulness and the hatred they had for one another and for their wives and their kids. He saw them repeatedly go against their own best interests as they were swayed and bedazzled by modern subliminal techniques, manipulated by politicians and corporate tycoons, who posed as their friends while sapping their energy. Whose political campaigns amounted to: “Get the Nigger.”

As always, Reed’s diagnosis of late 20th-century American culture seems to belong, unfortunately, just as much to our own time, giving his novels a perhaps-unintended sheen of prescience. Reed’s work points to dystopia, even as his heroes work for freedom and justice. And yet Reed gives equal air time to the forces that oppress freedom and justice, forces that find expression in “Louisiana Red”:

Louisiana Red was the way they related to one another, oppressed one another, maimed and murdered one another., carving one another while above their heads, fifty thousand feet, billionaires few in custom-made jet planes equipped with saunas tennis courts swimming pools discotheques and meeting rooms decorated like a Merv Griffin Show set….

The miserable workers were anti-negro, anti-chicano, anti-puerto rican, anti-asian, anti-native american, had forgotten their guild oaths, disrespected craftsmanship; produced badly made cars and appliances and were stimulated by gangster-controlled entertainment; turned out worms in the tuna fish, spiders in the soup, inflamatory toys, tumorous chickens, d.d.t. in fish and the brand new condominium built on quicksand.

As a means to fight the culture of erosion, decay, and entropy, Yellings founds the Solid Gumbo Works. Here, he manufactures a gumbo—a spell, really—to combat “Louisiana Red.” In the process he manages to cure cancer, which pisses off a lot of big corporations, and pretty soon Yellings is murdered. Papa LeBas is sent in from New York to solve the case.

Papa LeBas runs into trouble pretty quickly, mostly by way of Yellings’ adult children: Wolf, Street, Sister, and the provocative and gifted Minnie, who leads a group of militants called the Moochers. Each of the children seem to embody an allegorical parallel to some aspect of the American counterculture of the late sixties and seventies, allowing Reed to mash up genres and skewer ideologies. There are a lot flavors in this gumbo: voodoo lore and California history bubble in the same pot as riffs on astrology and Cab Calloway’s hit “Minnie the Moocher.” Reed frequently compares and contrasts East with West, New York with California, underscoring the latter’s anxieties of influence about being the New World of the New World. Throughout the novel, we get routines on Amos & Andy, slapstick pastiches straight out of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat comix, hysterical nods to Kafka. Reed plays off early blaxploitation films like Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song and Superfly (not to mention Putney Swope), and synthesizes these tropes with kung fu imagery and neo-Nazi nostalgia garb. He turns Aunt Jemima into a loa at one point.

Reed’s prose ping-pongs between genres, skittering from pulp fiction noir to surrealist frenzies, from bizarre sex to raucous action, from political essaying to postmodernist mythologizing. Through these stylistic shifts, Reed satirizes a host of ideologies that feed into “Louisiana Red.” Aspects of the Berkeley youth movement, radical feminism, free love, and intellectual hucksterism all get skewered, but through an allegorical lens—Reed dares us, often explicitly (by way of a character named Chorus) to read Louisiana Red as an allegorical retelling of Sophocles’ Antigone.

This retelling is both tragic and comic though, premodern and postmodern, a carnival of varied voices. The chapters are short, the sentences sting, and the plot shuttles along, pivoting from episode to episode with manic picaresque glee. Reed’s narrator is always way out there in front of both the reader and the novel’s characters, hollering at us to keep up.

Ultimately, The Last Days of Louisiana Red is a bit of a shaggy dog. It’s not that it doesn’t have a climax—it does, it has lots of climaxes, some quite literal. And it’s not that the novel doesn’t have a point—it very much does. Rather, it’s that Reed employs his detective story as a frame for the larger argument he wants to make about American culture. Sure, Papa LaBas gets to the bottom of Yellings’ murder, but that’s not ultimately what the narrative is about.

When we get to the final chapter, we find LaBas, sitting alone “on a plain box” in the empty offices of the Solid Gumbo Works reflecting on the case in a way that, in short, sums up what The Last Days of Louisiana Red is about:

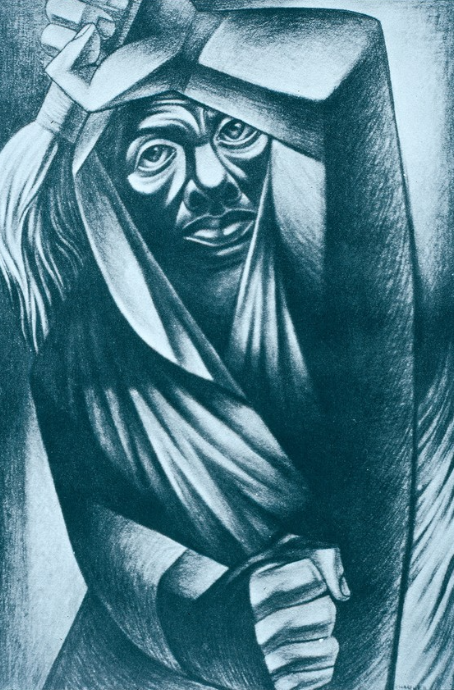

He thought of the eaters and the eaten of this parable on Gumbo…all ‘oppressed people’ who often, like Tod Browning ‘Freaks,’ have their own boot on their own neck. They exist to give the LaBases, Wolfs and Sisters of these groups the business, so as to prevent them from taking care of Business, Occupation, Work. They are the moochers who cooperate with their ‘oppression,’ for they have the mentality of the prey who thinks his destruction at the fangs of the killer is the natural order of things and colludes with his own death. The Workers exist to tell the ‘prey’ that they were meant to bring down killers three times their size, using the old morality as their guide: Voodoo, Confucianism, the ancient Egyptian inner duties, using the technique of camouflage, independent camouflages like the leopard shark, ruler of the seas for five million years. Doc John, ‘the black Cagliostro,’ rises again over the American scene. The Workers conjure and command the spirit of Doc John to walk the land.

So here, near the end of The Last Days of Louisiana Red, Papa LeBas—and Ishmael Reed, of course—conjures up the spirit of Doctor John, the voodoo healer who escaped slavery and brought knowledge of the hoodoo arts to his people. There’s a promise of hope and optimism here at the novel’s end, despite its many bitter flavors. But the passage cited above is not the final moments of Louisiana Red—no, the novel, ends, despite what I wrote about its being a shaggy dog story, with a marvelous punchline.

Ishmael Reed remains an underappreciated novelist whose early work seems as vital as ever. The Last Days of Louisiana Red is probably not the best starting place for him, but it’s a great novel to read right after Mumbo Jumbo, which is a great starting place to read Reed. In any case: Read Reed. Highly recommended.

[Ed. note–Biblioklept first published this review in March, 2019.]