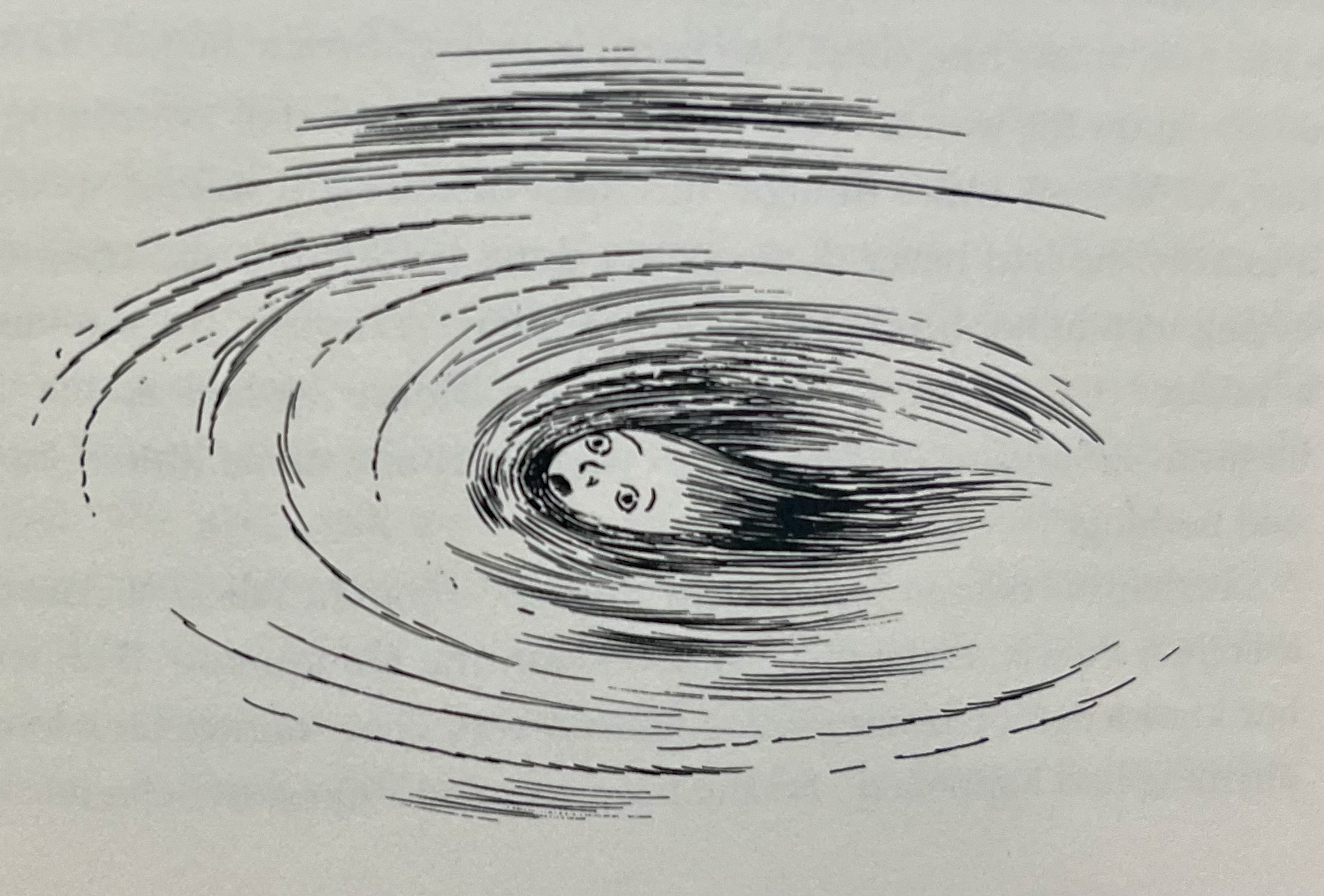

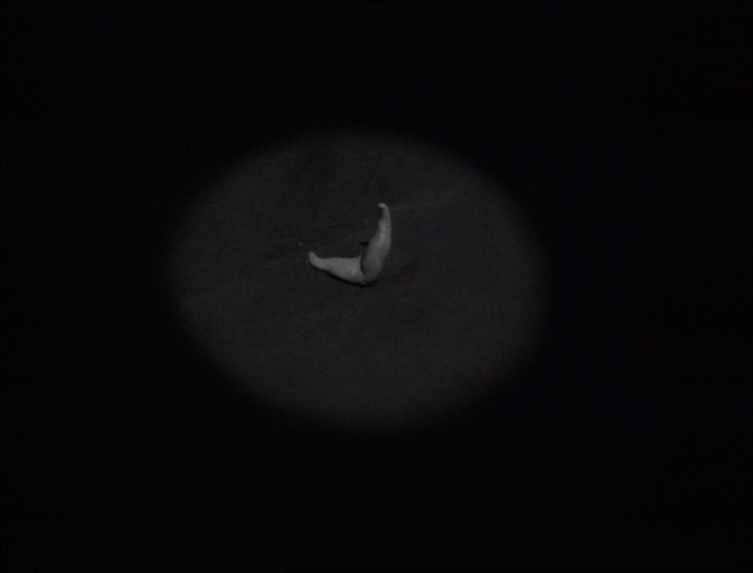

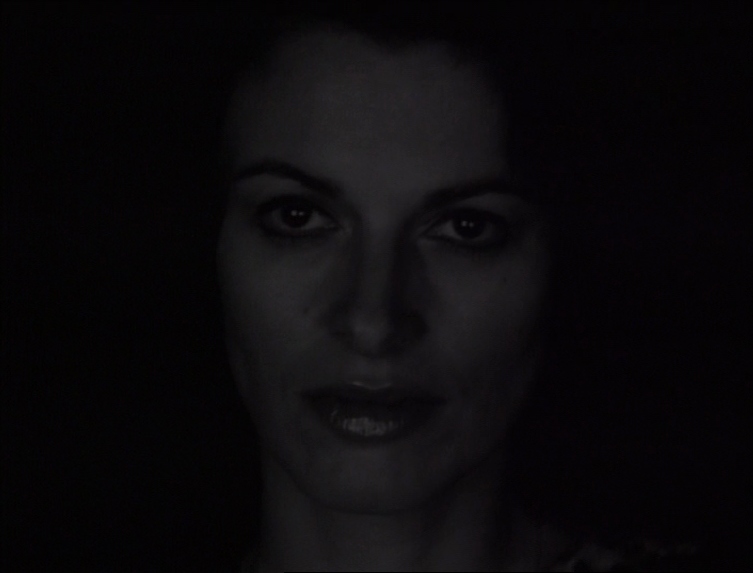

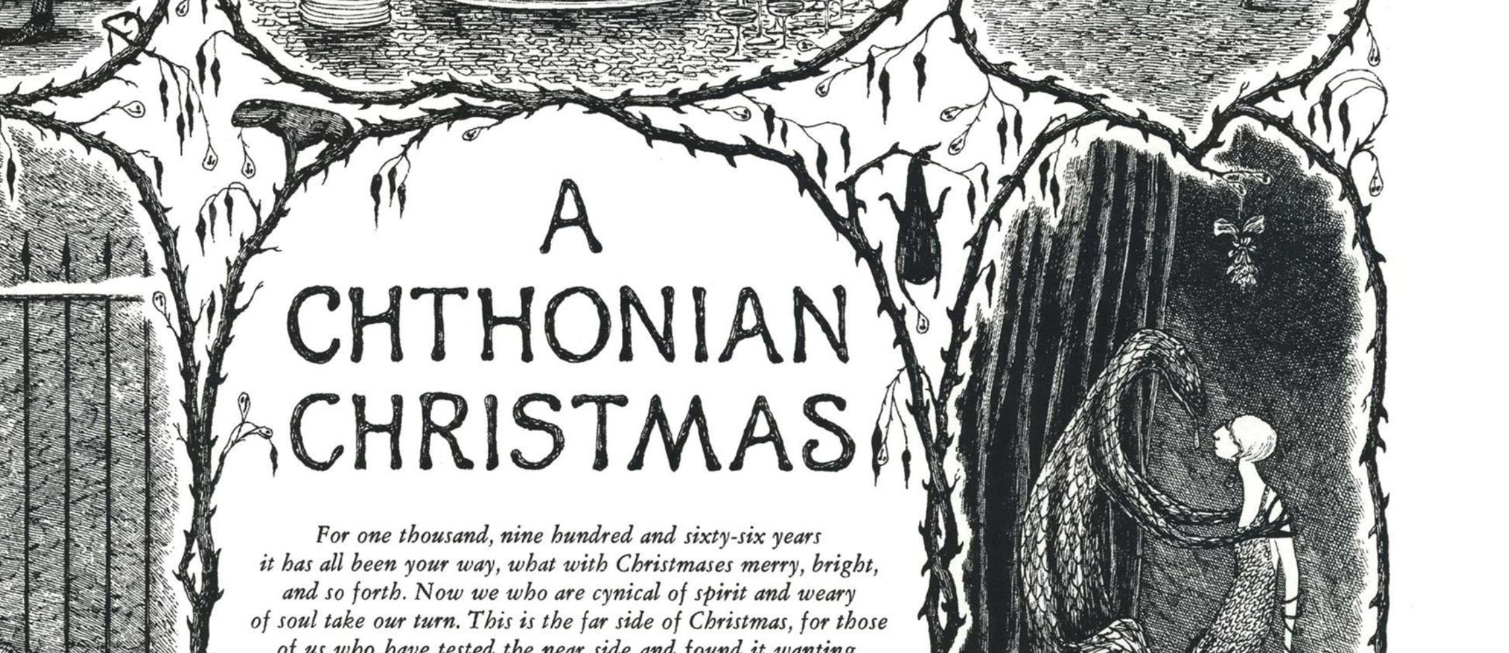

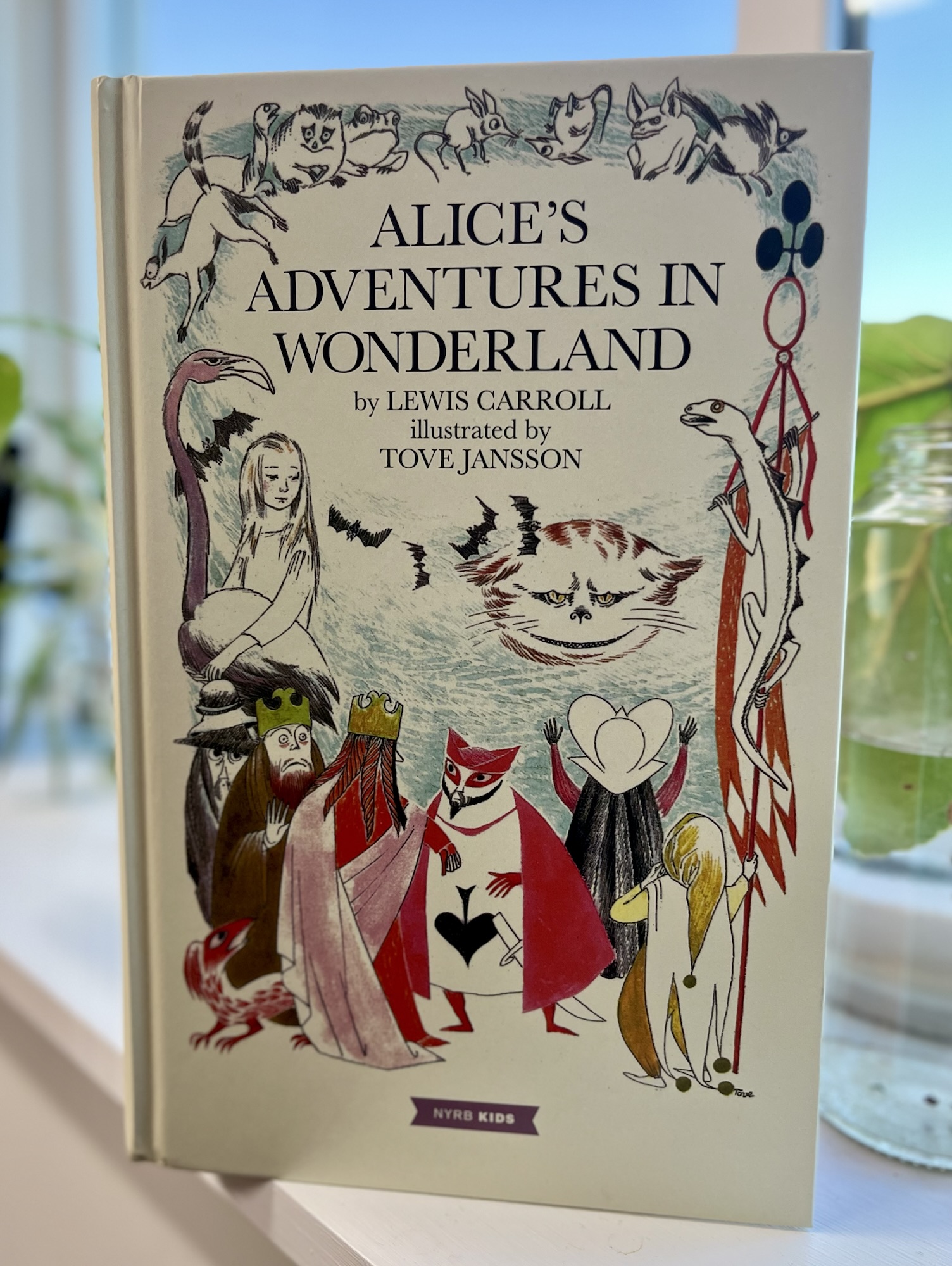

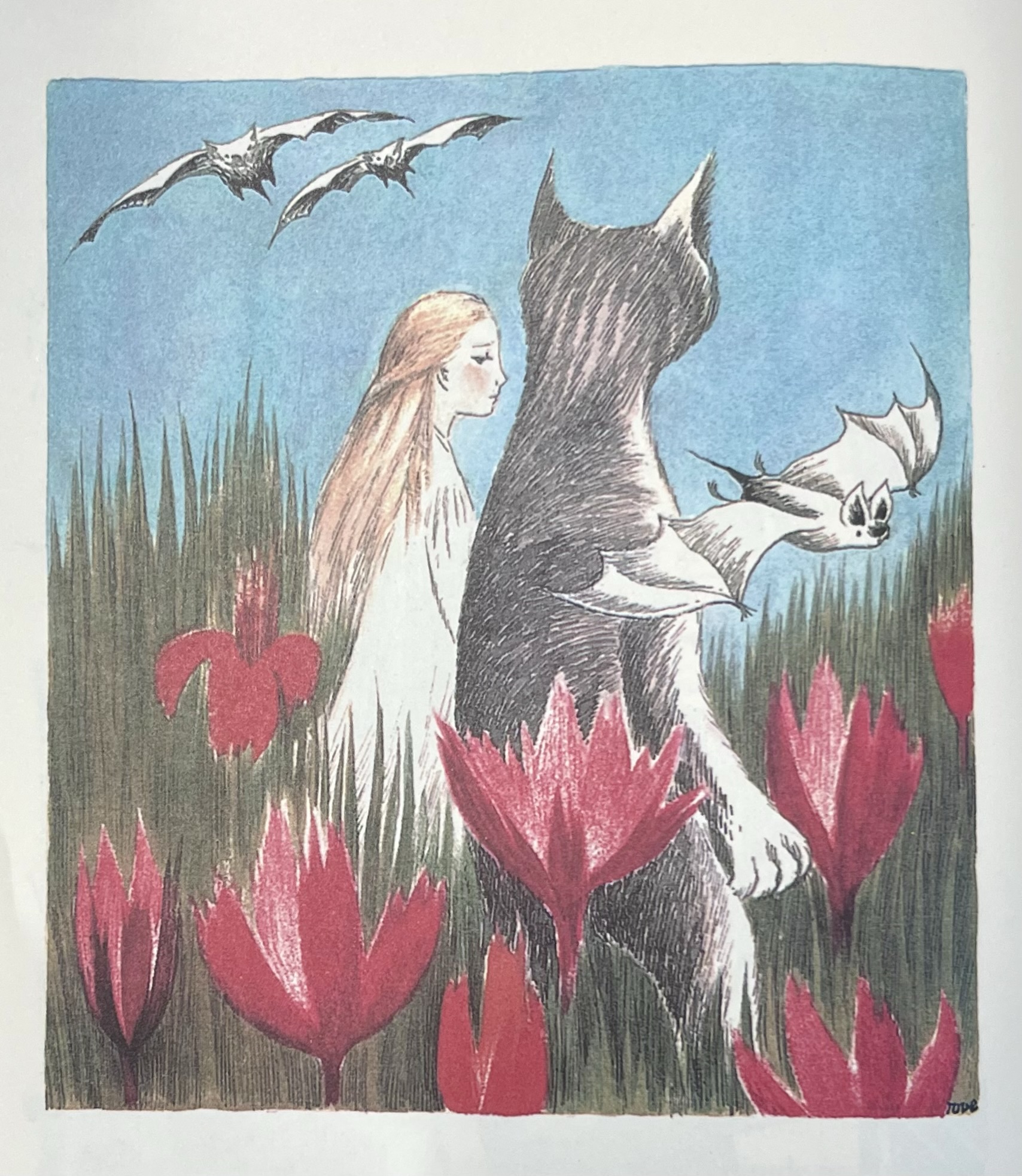

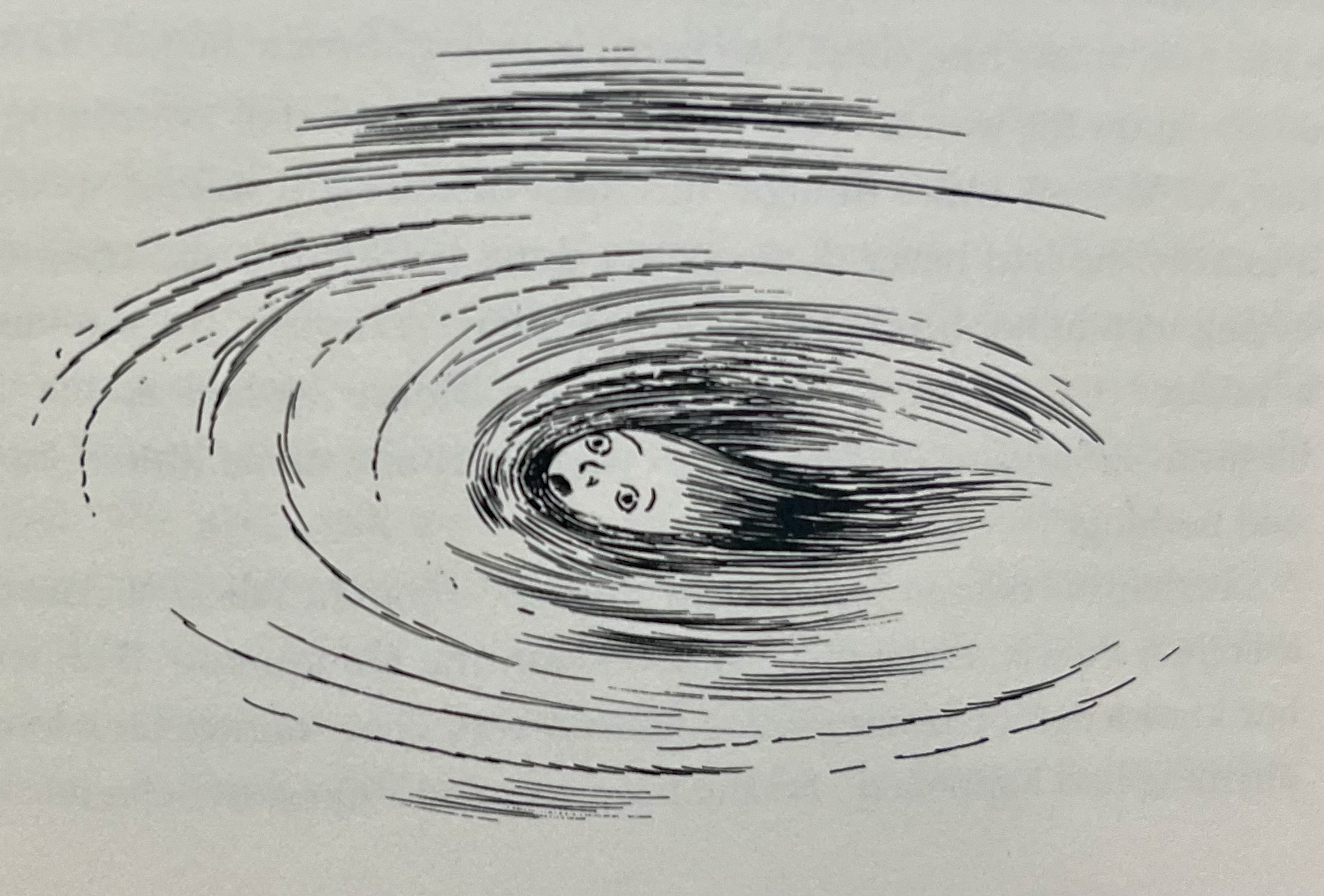

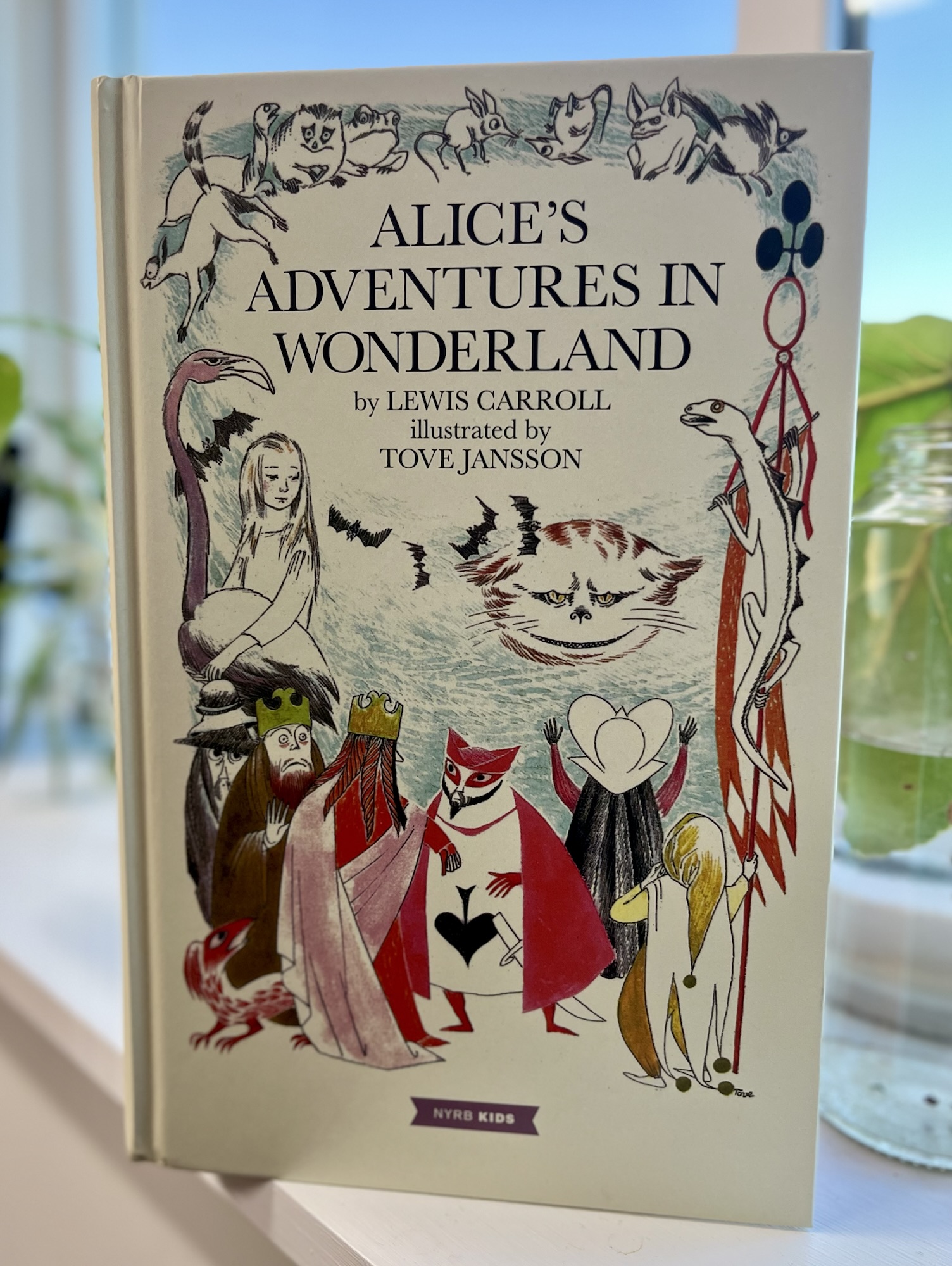

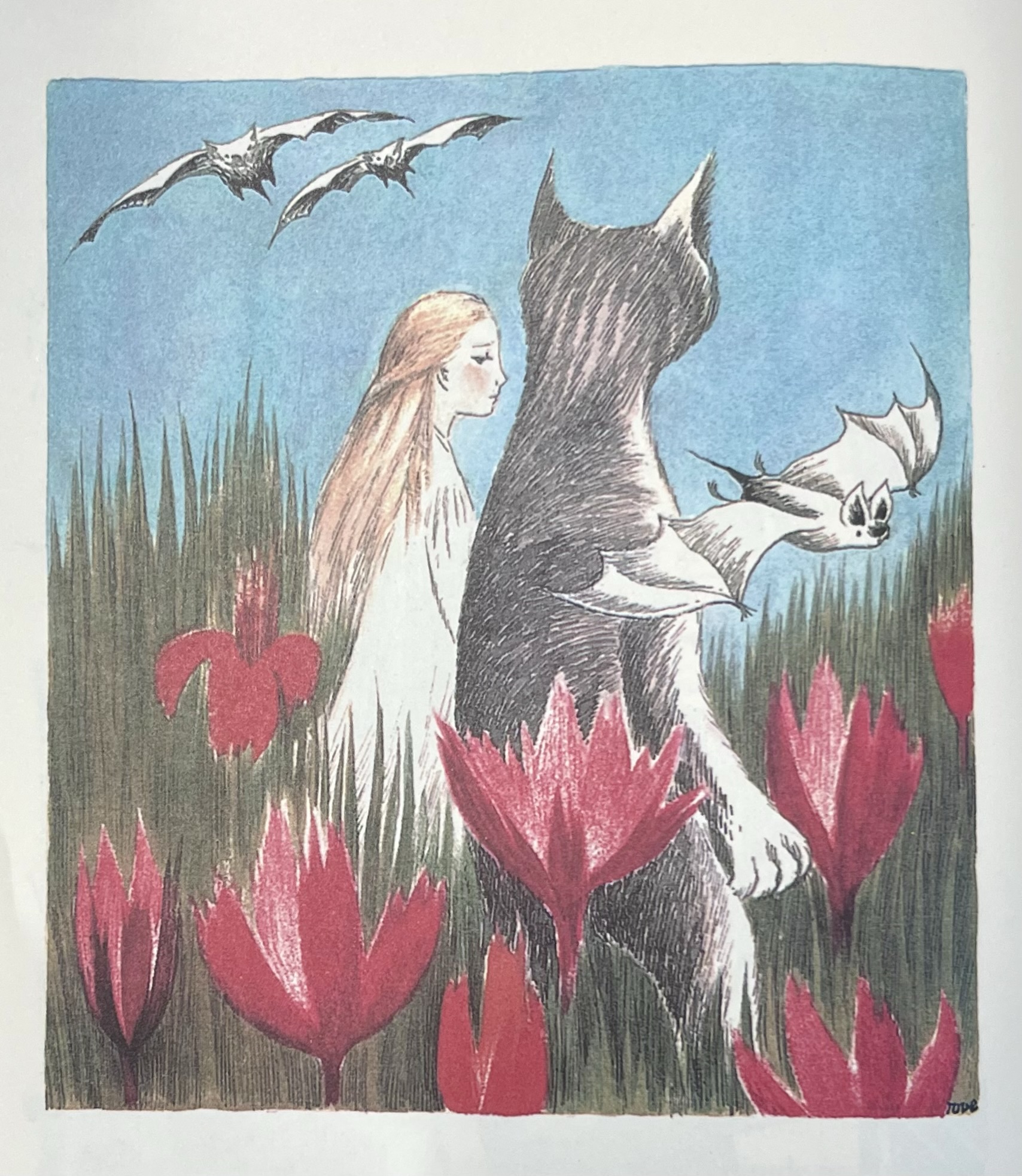

This fall–just in time for the holiday season–the NYRB Kids imprint has published an edition of Lewis Carroll’s classic Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland illustrated by the Finnish author and artist Tove Jansson. Jansson is most famous for her Moomin books, which remain an influential cult favorite with kids and adults alike. She illustrated Carroll’s Alice in 1966 for a Finnish audience; this NRYB edition is the first English-language version of the book. There are illustrations on almost every page of the book; most are black and white sketches — doodles, portraits, marginalia — but there are also many full-color full-pagers, like this odd image about a dozen pages in:

Here we have Alice and her cat Dinah, transformed into a shadowy, even sinister figure, large, bipedal. Bats float in the background, echoing Goya’s famous print El sueño de la razón produce monstruos. The image accompanies Alice’s initial descent into her underland wonderland: “Down, down, down. There was nothing else to do, so Alice soon began talking again,” addressing Dinah, who will “miss me very much to-night, I should think!” Wonderlanding if Dinah might catch a bat, which is something like a mouse, maybe, “Alice began to get rather sleepy, and went on saying to herself, in a dreamy sort of way, ‘Do cats eat bats? Do cats eat bats?’ and sometimes, ‘Do bats eat cats?; for, you see, as she couldn’t answer either question, it didn’t much matter which way she put it.” Jansson’s red flowers suggest poppies, contributing to the scene’s slightly-menacing yet dreamlike vibe. The image ultimately echoes the myth of Hades and Persephone.

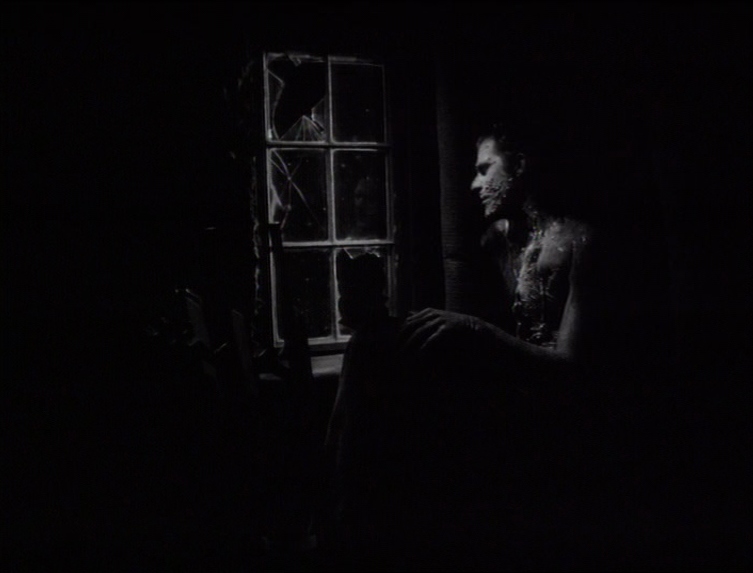

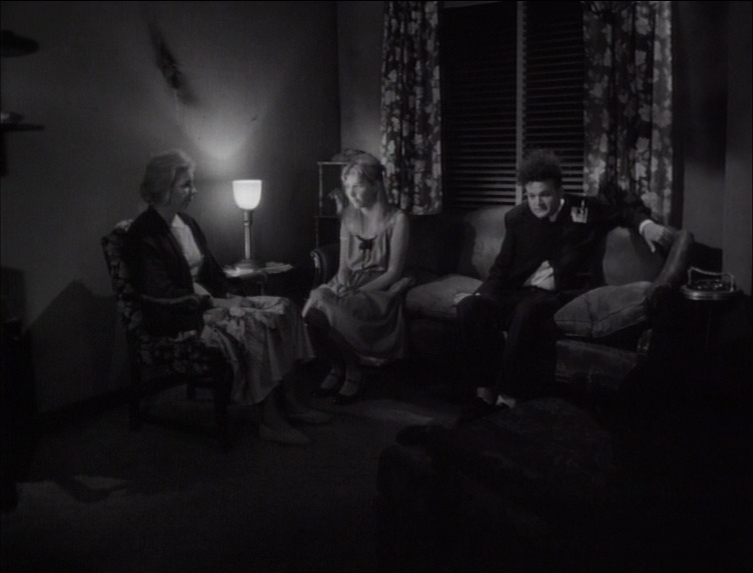

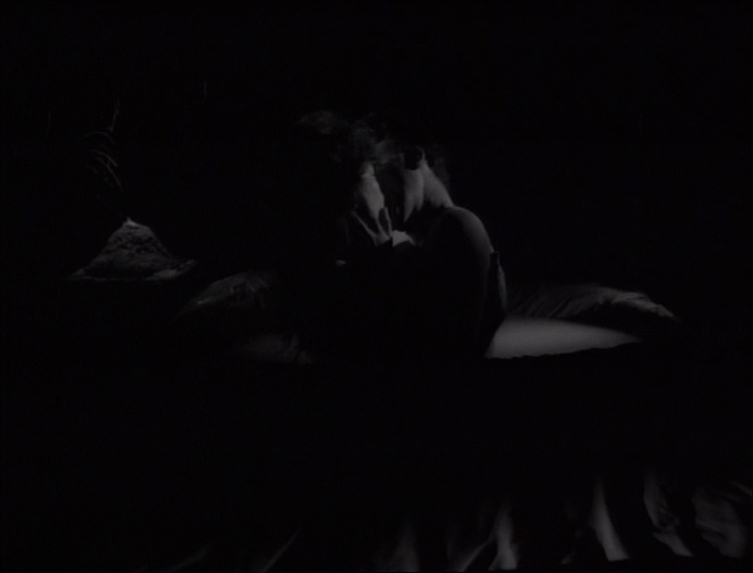

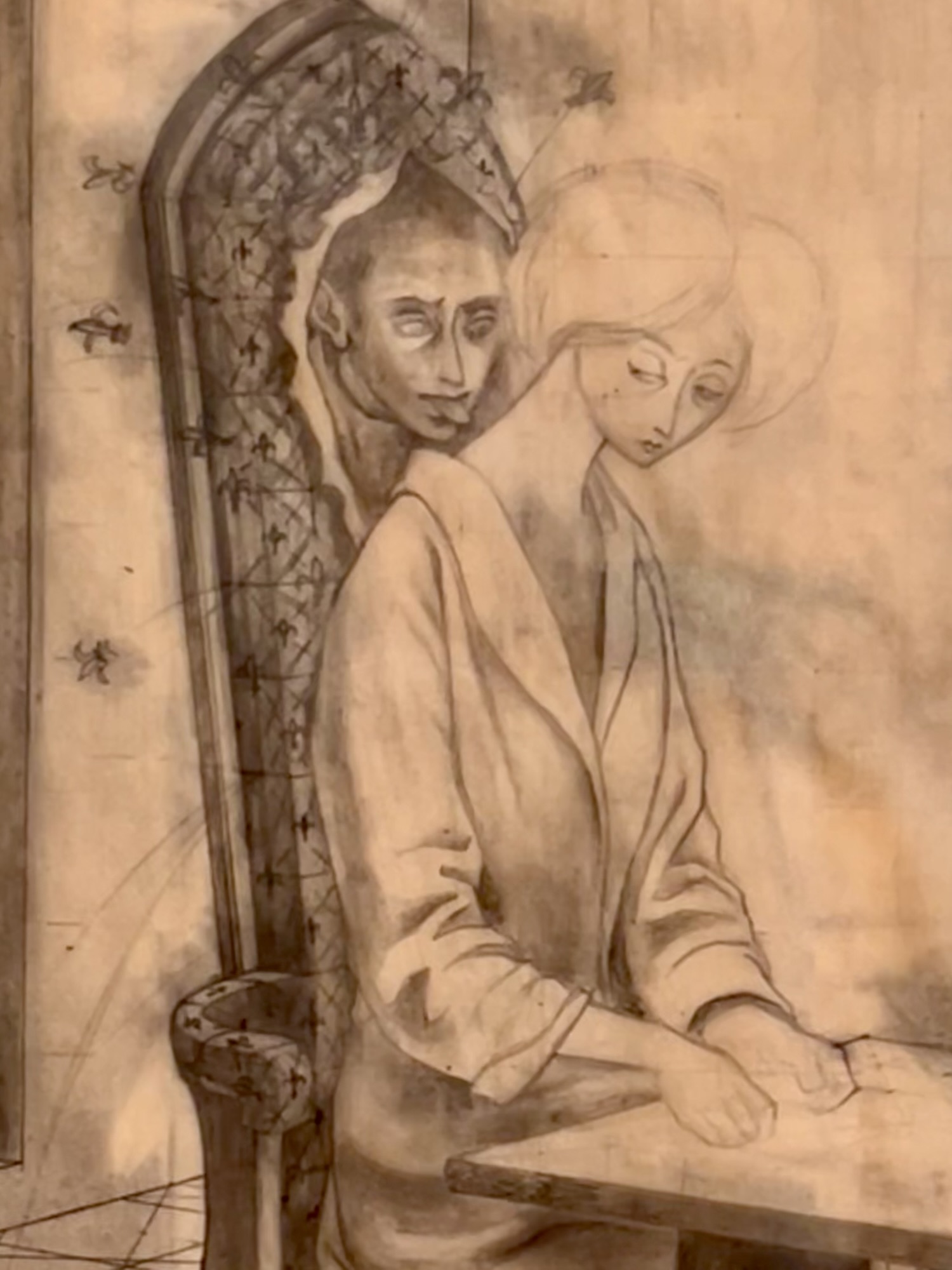

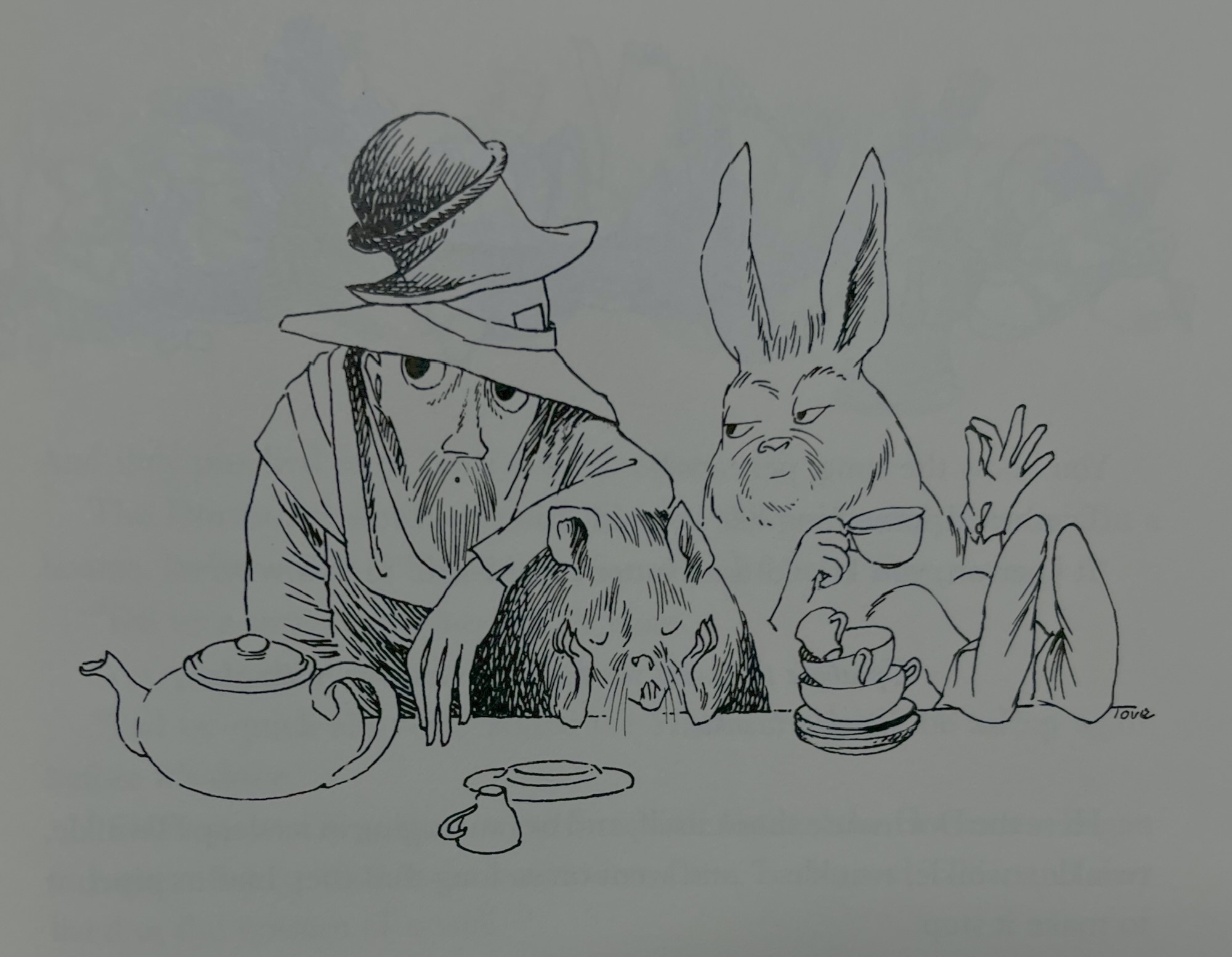

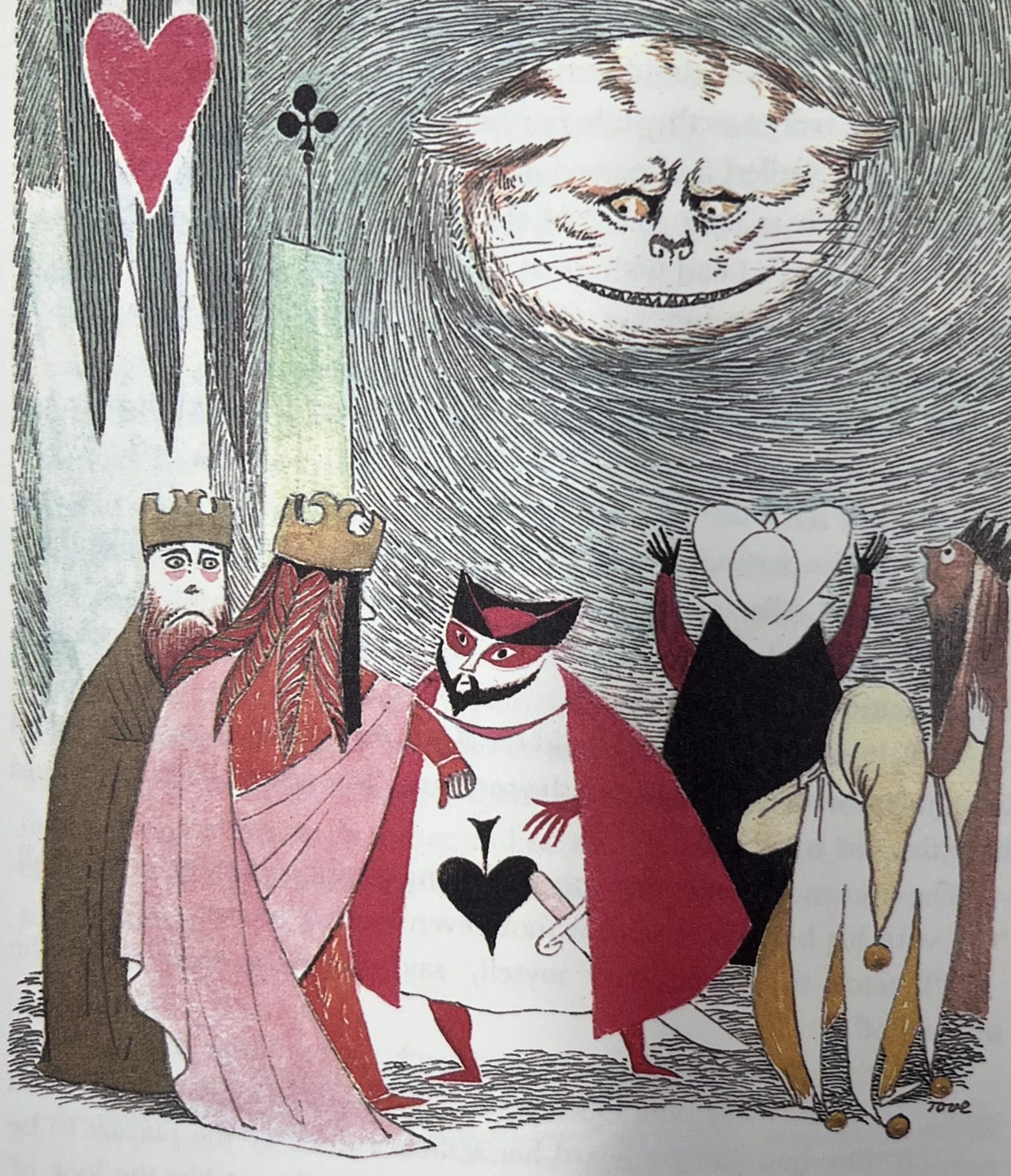

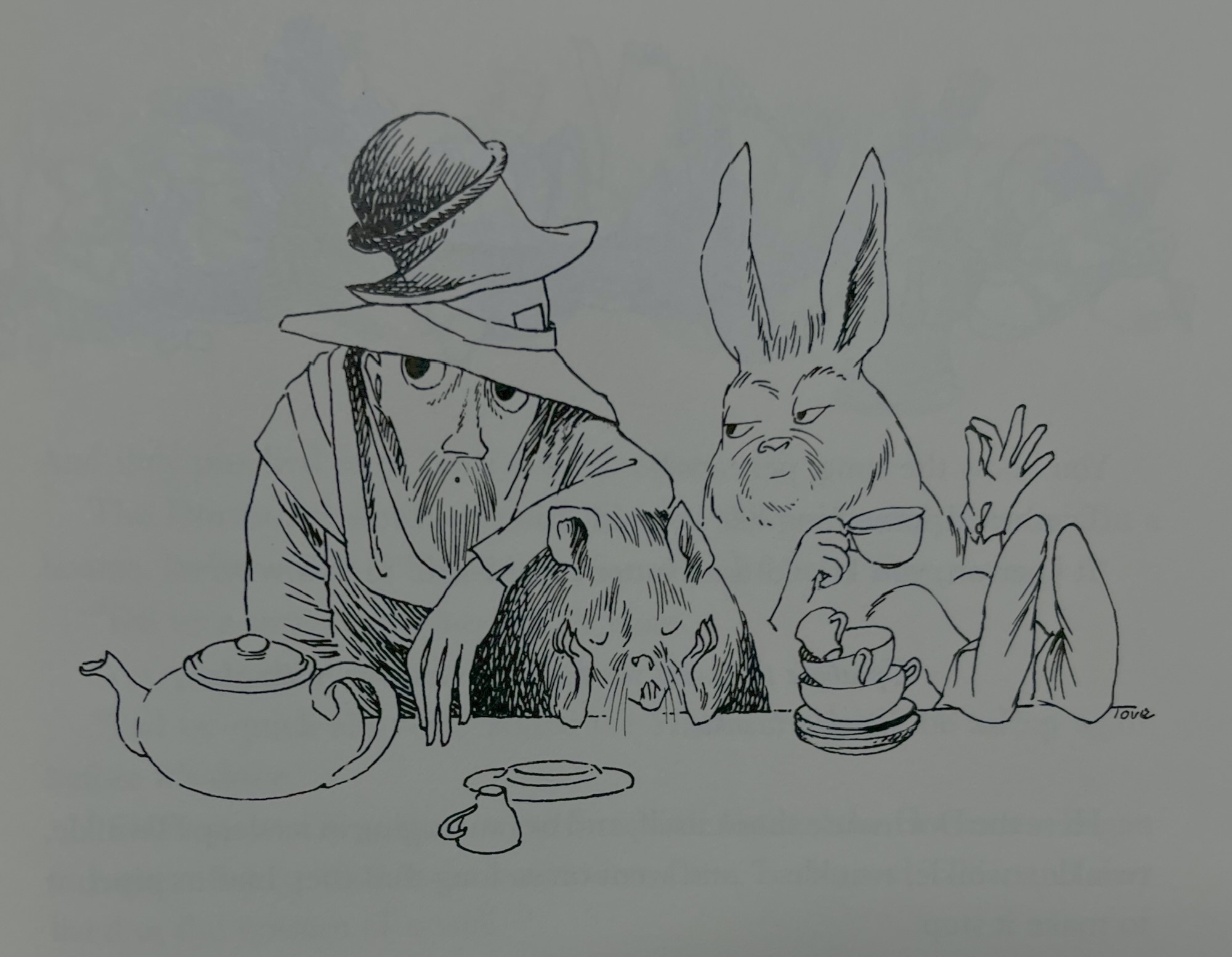

All the classic characters are here, of course, rendered in Jansson’s sensitive ink. Consider this infamous trio —

There was a table set out under a tree in front of the house, and the March Hare and the Hatter were having tea at it: a Dormouse was sitting between them, fast asleep, and the other two were using it as a cushion, resting their elbows on it, and talking over its head.

I love Jansson’s take on the Hatter; he’s not the outright clown we often see in post-Disneyfied takes on the character, but rather a creature rendered in subtle pathos. The March Hare is smug; the Dormouse is miserable.

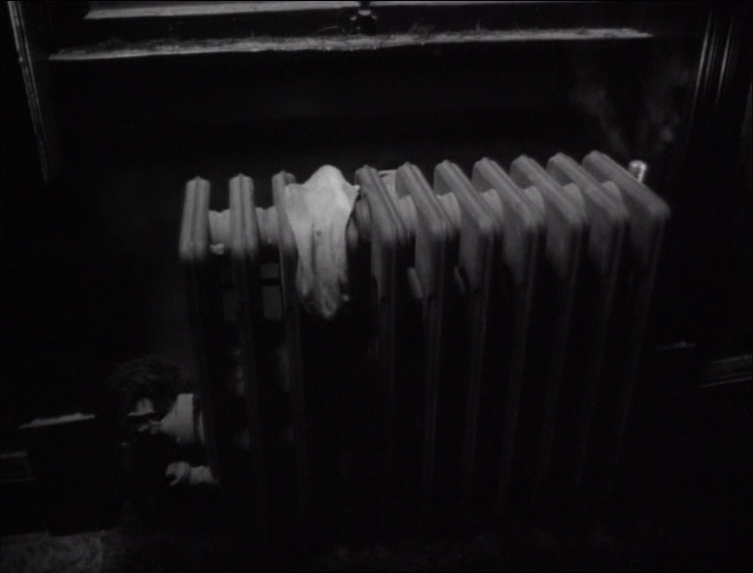

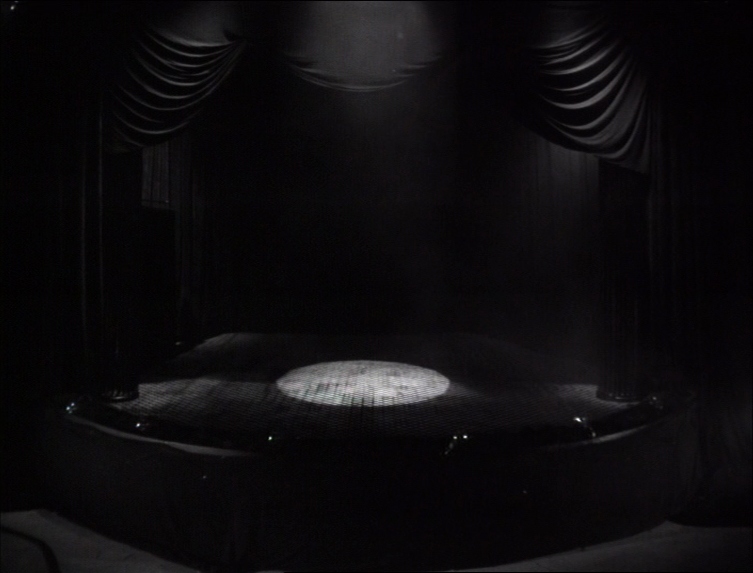

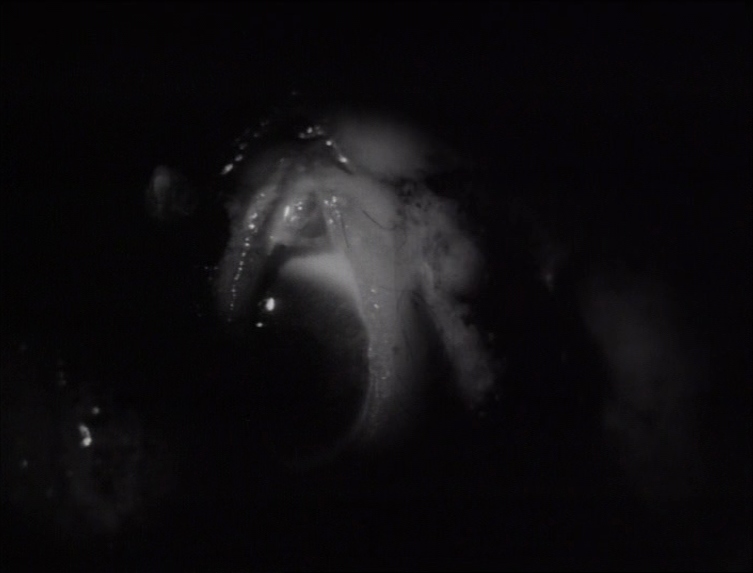

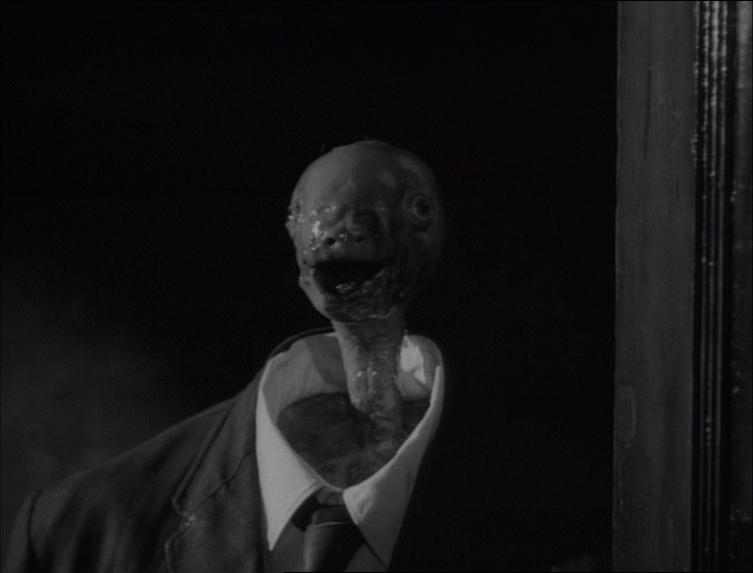

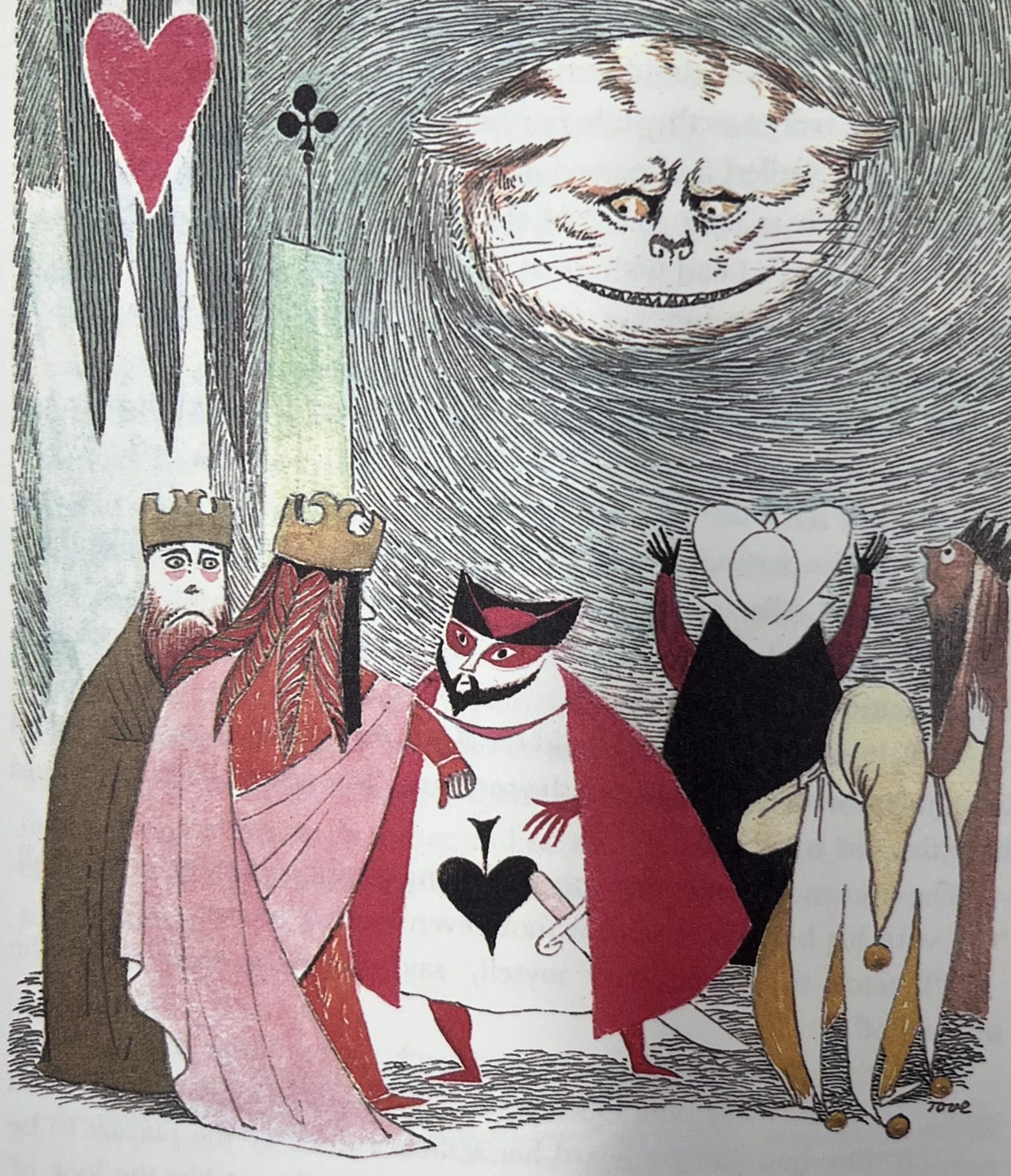

And you’ll want a glimpse of the famous Cheshire cat who appears (and disappears) during the Queen’s croquet match:

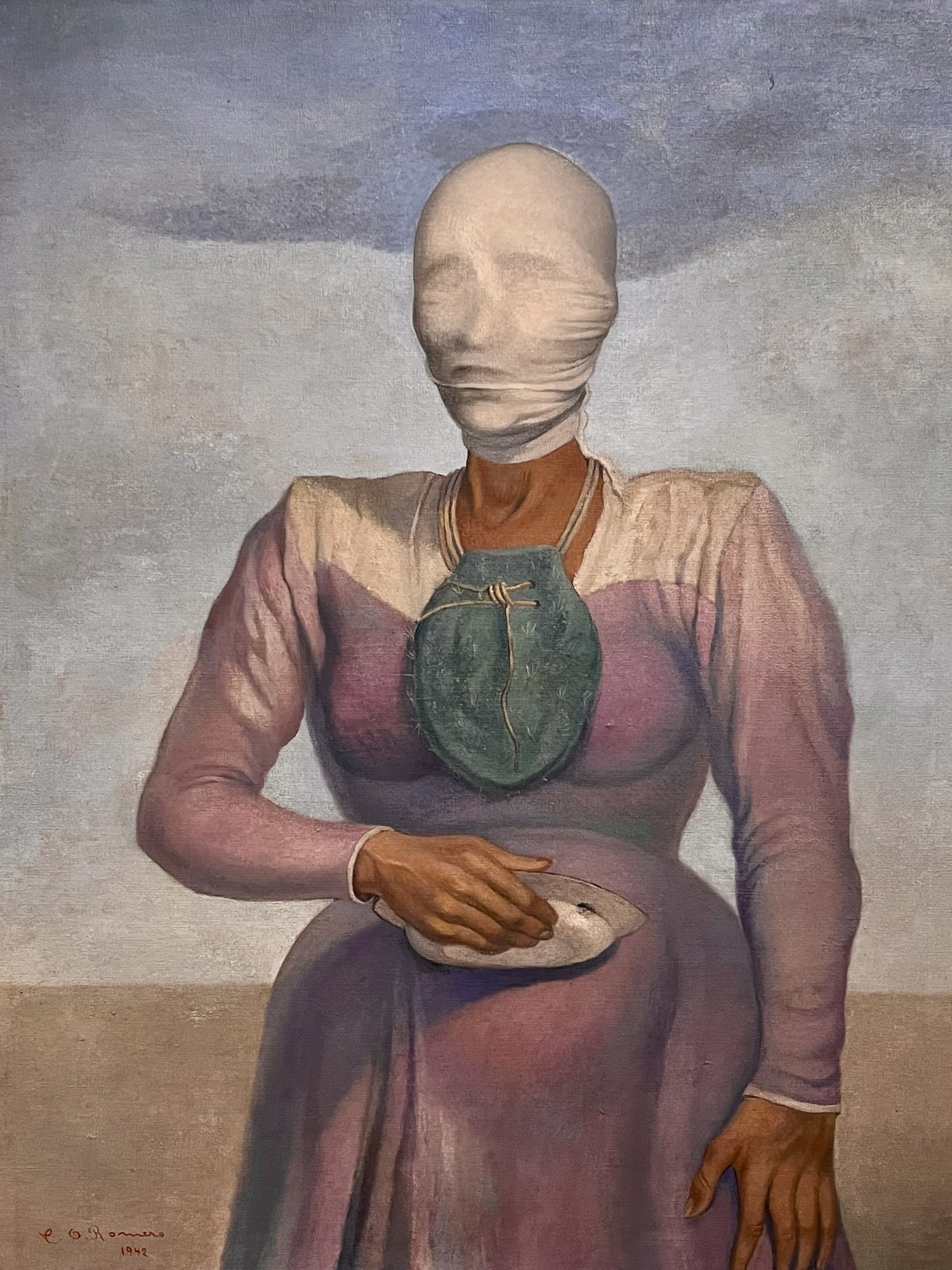

Jansson’s figures here remind one of the surrealist Remedios Varo’s strange, even ominous characters. Like Varo and fellow surrealist Leonora Carrington, Jansson’s art treads a thin line between whimsical and sinister — a perfect reflection of Carroll’s Alice, which we might remember fondly as a story of magical adventures, when really it is much closer to a horror story, a tale of being sucked into an underworld devoid of reason and logic, ruled by menacing, capricious, and ultimately invisible forces. It is, in short, a true reflection of childhood,m. Great stuff.