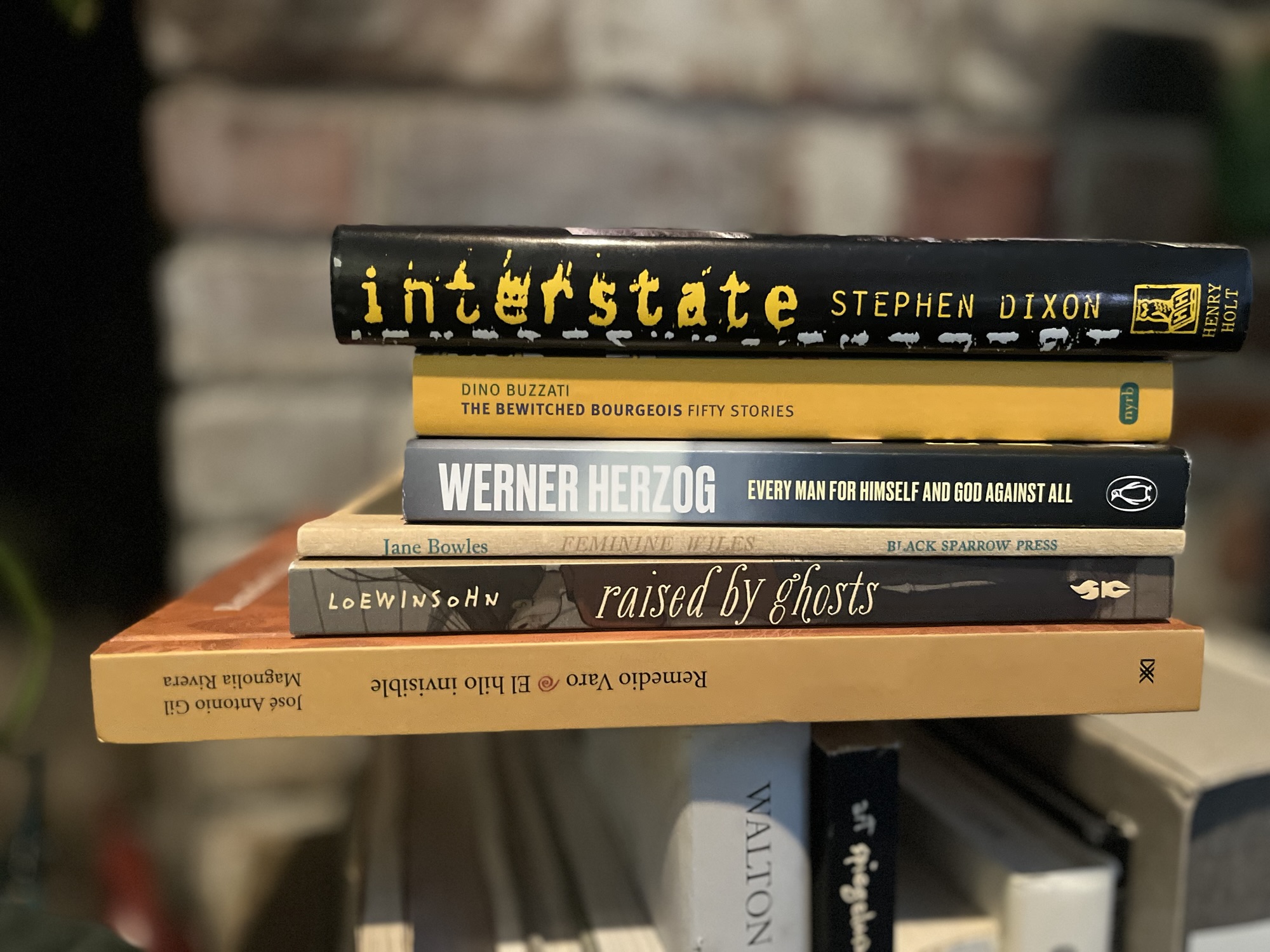

A passage from Stephen Dixon’s novel Interstate

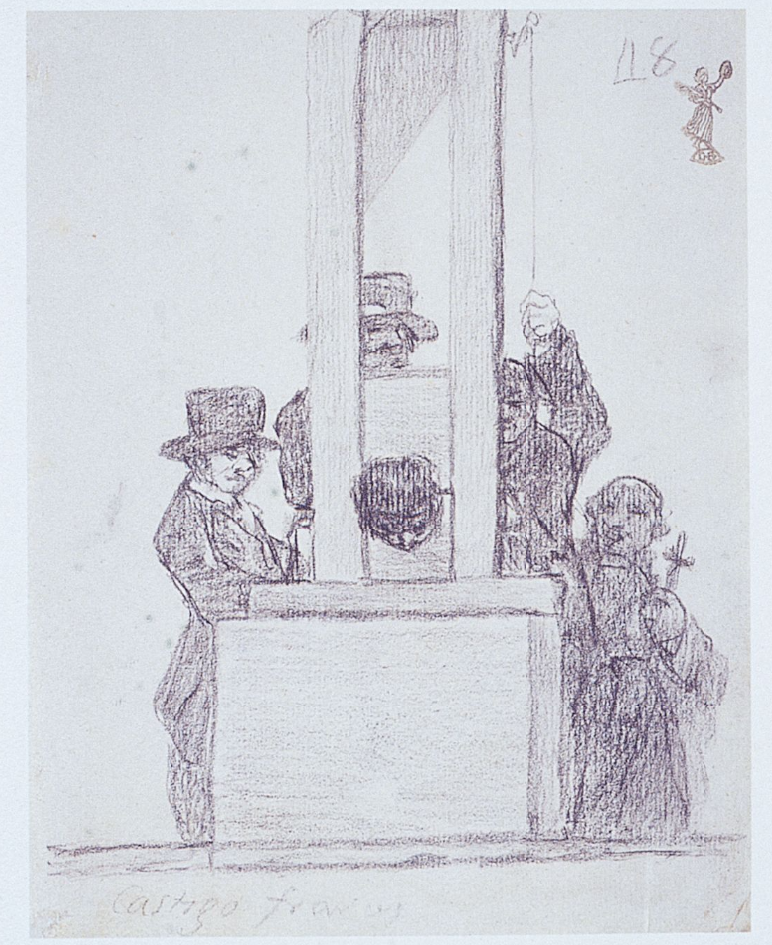

So you go with the doctor to the room Julie’s in and the doctor says, right outside it—door closed, no little window in it, legs so weak while you walked that the doctor had to hold your arm, you said “I think I’m going to fall, grab me,” and he did, while you walked you thought “It’s like an execution I’m going to, mine, hanging, shooting, injection, gas; fear, weakness, feeling you want to heave,” sign on the door saying “Do Not Enter, Medical Staff Only, Permission Required”—“She’s in there on the bed. It’s not really a bed, we call it something else, but for our purposes we’ll call it that.” “What do you call it normally, meaning the technical calling—the word, you know?” and he says “‘Bed’ will do.” “But I’d like to know, if you don’t mind. I’m not sure why, peculiar reasons probably, but just, could you?” “An examination table, that’s all it is, but now it’s made up to look like a bed—sheets, a pillow.” “For under her head.” “Under her head, yes.” “You’re giving me a lot of your time, I’m sorry.” “It’s okay, what I do.” “I’ve been thinking of her head, only before, I think, on a pillow when she was alive. Everybody’s sure she’s dead?” He nods. “Then I’ll see her in there. I mean, I would, of course, if she were alive, but I’m saying for now.” You put your hand on the door. It has no knob or bar, only needs a push. Which side of the room will the bed be? The left, you guess. But it’s a table, so may be in the middle. “Yell for me, ‘Dr. Wilkie,’ if all of a sudden you need assistance. Or if you want, I’ll come in with you.” “You’ve seen her?” “Uh-huh.” “No, I want to see her alone.” “I can go in and leave when you want. Or with a flick of your finger, if you can’t speak, or point to the door.” “Nah, I want it to be now just me and her. ‘Me and she’ sounds better but it’s ‘me and her, me and her.’ Meaning, they go together, correctly, though in that case it could be ‘she and I’ for all I know. Why do I bring these things up? Delaying.” “No matter what, I won’t budge from here unless there’s an emergency I’m absolutely needed for. Chances of that are minimal, and I’ve asked another doctor to fill in for me. But you never know.” “You never know,” you say. “And I suppose I should go in now, get it over with. Somehow I imagine her in the middle of the room on that table-bed, head on the left side of it, so, perpendicular to us,” and you show with your hands in a T what you mean. “I believe that’s the way it is.” “So there. And all my life, you know, I’ve been getting things over with—no window in the room, probably.” “None.” “Lots of lights, some side tables with instruments and things on them, and so on. In fact, there’s a standard joke, a running one, rather, around my household—no, it’s no time for lines or jokes. This isn’t one, what I was about to say, but might sound like it. I haven’t told you it yet?” “If you mean now or before, not that I know of.” “I think I’ve told everyone else in the world. I have so few things to say. Of interest. Though it always had a serious degree to it. Side. It borders. Straddles.” “Go on, tell me if it’ll help relax and prepare you for going inside. Remember, here and now, anything you do or say is okay.” “Right, better I feel that way, relaxed, prepared, so I don’t crash first thing on seeing her, my dear kid, truly the dearest little girl-child-kid there ever was,” and you start crying and you cry and say “Everybody says ‘ever was,’ I bet, everybody, in a situation like this, and I should stop all this kind of talk. Just saying it, of course I know what it’ll do, so I have to wonder if I didn’t say it just to go to pieces and delay some more my going in. There,” patting yourself under the eyes, tears, “these goddamn these. Stop, stop, stop,” slapping your cheeks. “But my nonjoke. Nonintended for one, the something I was going to say and will probably say it that I said might sound like a joke, and other times it could be. Now it’s just a fact. An insight into me. So I’m telling it as an illustration of my always wanting to get things over with—trips, books, days, work, housecleaning, even sex sometimes. Cooking, quick, quick, quick. A joke to everyone I know, I can tell you, as if work to get rid of to clear yourself for the real or more important work, stuff that’s killing you for you to do and which turns out to be the same thing, get rid of it, clear yourself for something else, and so on. So say it. Or do it. My hand’s on the door again but I’m not pushing it even a quarter-inch. I can’t seem to get in there. Whyever why? The example’s this. That I want on my tombstone for it to read—Rather, that I want my epitaph to say on my tombstone, chiseled in—Rather, for ‘tombstone’ sounds so Western western—in other words, fake—that I want my head-or footstone—my gravestone epitaph to say, you know, under my name, birth and death dates—anywhere on the stone—‘So, I got it over with.’ Just that. You see the point; message is clear, isn’t it? It’s not funny now. Of course, nothing is, goes without saying, and long way I told the story, end of it was dead before I got there,” dropping your head, crying again, hand off the door. “This is too hard. Impossible. Why does it have to be? Her, I mean. I know, old question, but couldn’t this all somehow be a wake-up dream? All that’s done-before crap too, everybody must say it in a situation like this, and especially to you, true?” “But any other time your epitaph line would be humorous. I understand that. You got it over with—you’re a man who likes getting things over with, and the big thing, the biggest, life, you’re saying in this fictitious epitaph, you did.” “Maybe it was ‘Well, I finally got it over with’ what I told my wife and friends countless—endless amounts—countless times. Or no ‘well,’ but a ‘finally.’ So just ‘I finally’—and no ‘so’ either, so just i finally got it over with.’ I think that’s it. It is. Anyway, what’s the damn difference? One of those. And I should get it over with, finally. I know I have to see her, I want to.” “You’re right when you imply I know how difficult it is,” he says. “I’ve been through this with plenty of other people.” “Other fathers? But ones who adore their kids? Love them, adore them, worship them; if there was one word for those three, then that?” “Fathers, mothers, husbands, children for their sisters or brothers—everyone close.” “Okay. You close your eyes, you hold your breath, you push open the door and walk in. That’s all you have to do, just those.” You do them, push the door shut behind you without turning around, let your breath out and smell; nothing unusual, something medicinal; and open your eyes.