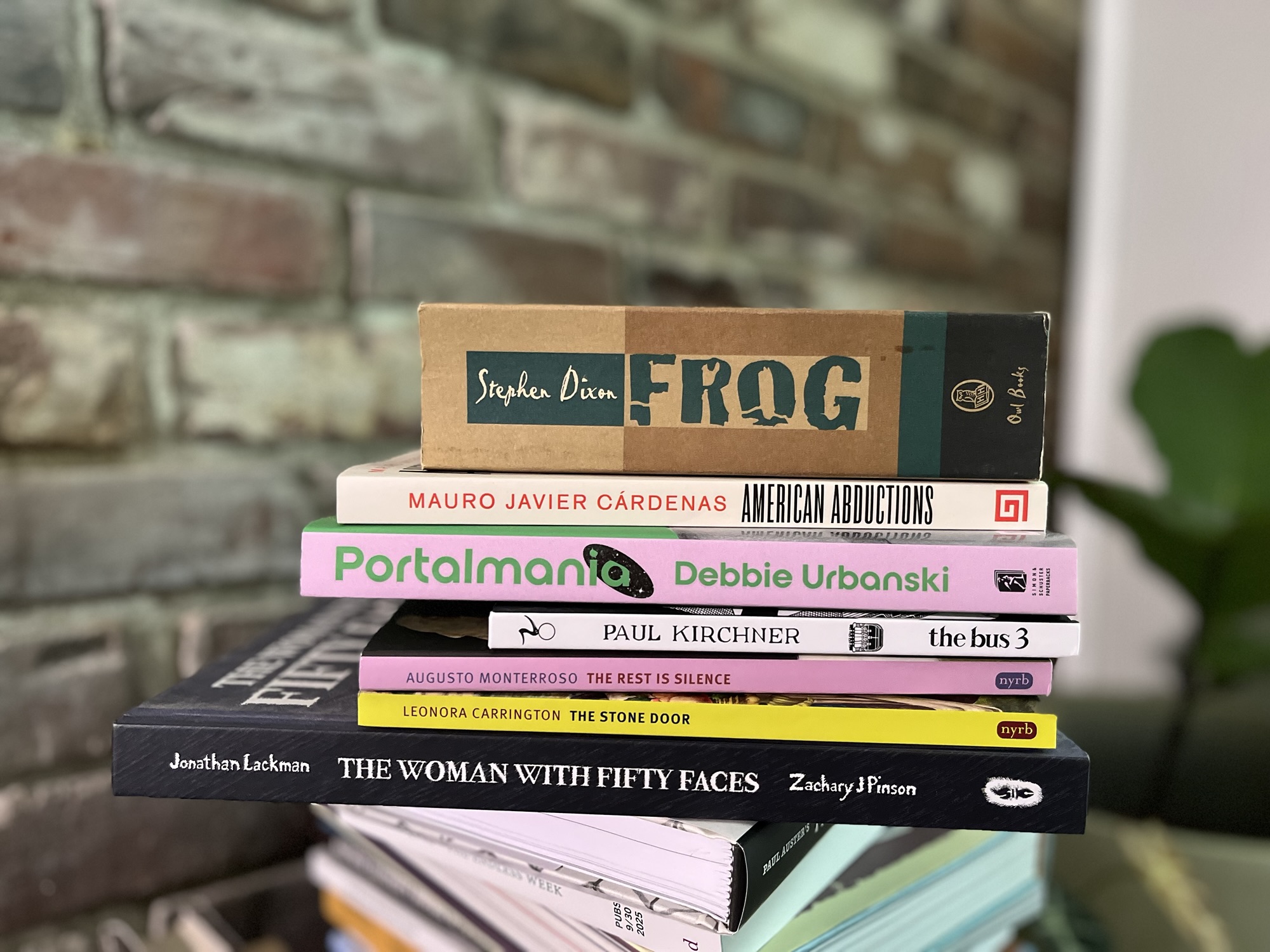

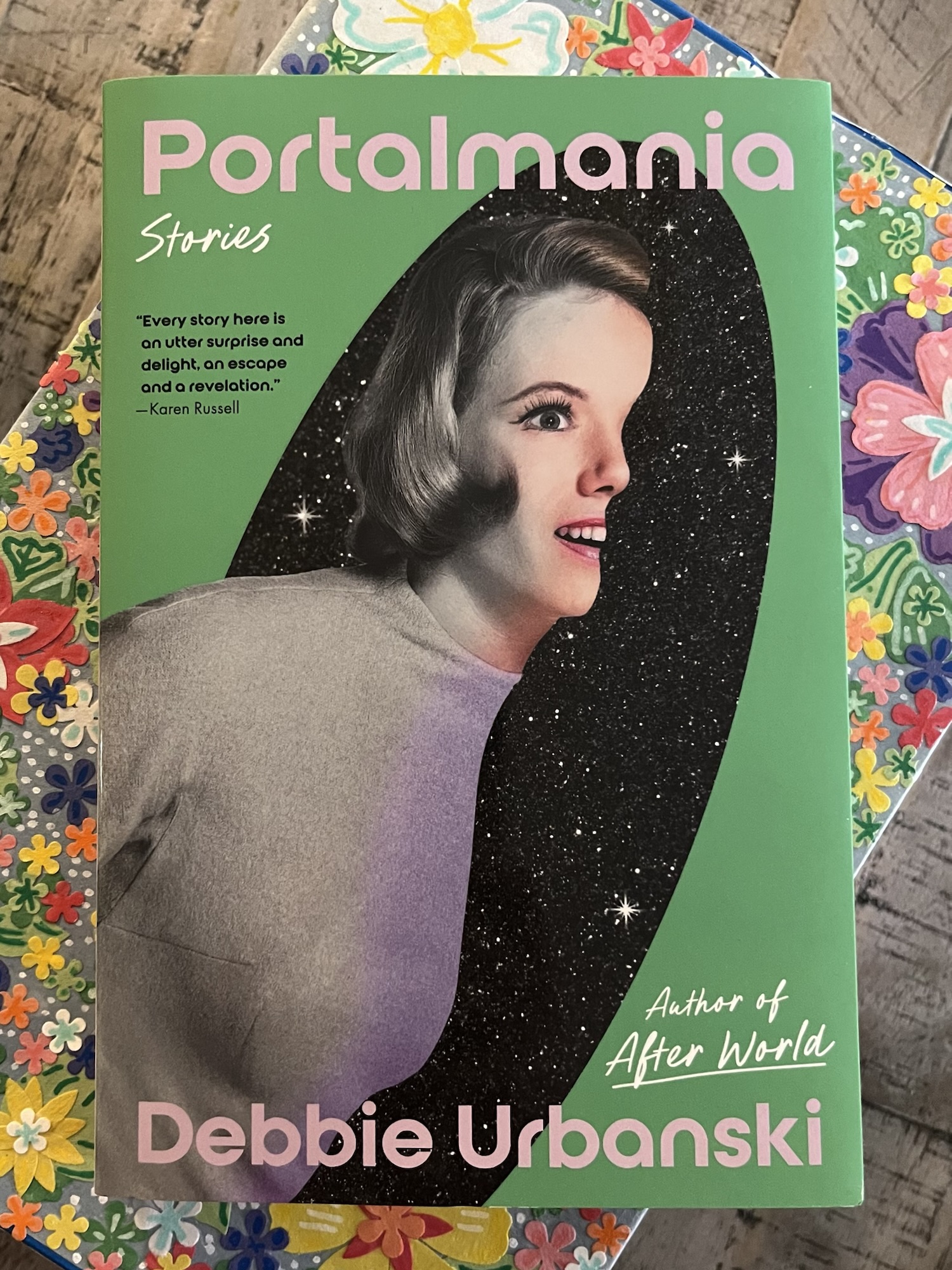

Debbie Urbanski’s new collection Portalmania is a metatextual tangle of science fiction, fantasy, and horror where portals don’t offer escape so much as expose the fractures beneath family, love, and identity. Her characters navigate asexuality, neurodivergence, and the quiet violence of domestic life against an uneasy backdrop of porous reality. At any moment a portal might appear, or a mutation might take hold, or, a wife might sell her daughter to a witch to assassinate her husband. Nothing is stable in Portalmania.

There are nine stories in Portalmania. Or maybe there are ten stories. Or eleven. Or maybe thirteen. If there are thirteen stories, maybe I could riff on that Wallace Stevens poem for my review titles (that would be too fucking precious and obnoxious though, wouldn’t it).

There are nine or ten or eleven or thirteen discrete “stories” in Portalmania, depending on how you want to count or what you want to count as a discrete story. But this need to count, or, more precisely, to pin down what-something-is-and-is-not, runs counter to the spirit of Portalmania, whose heroes push back on the definitions that are literal placeholders, linguistic lines that bind identities.

Perhaps the biggest through-line of the nineteneleventhirteen stories in Portalmania is the big ole question: What is love? In the story “How to Kiss a Hojacki,” a character puts the problem succinctly, writing a note to her husband: “We need to redefine love.”

The opening story, “The Promise of a Portal,” helps to establish a realistic world punctured by magical sci-fi. In “Promise,” we come to understand portals as personal escape hatches away from the humdrum domesticity of family life. “I think you can love people–children, mothers–and still want to leave them,” the hero of the story muses. These same portals pop up throughout the collection, creating continuity so that the nine (or are we saying thirteen? I misremember) stories here read more like a loose, discontinuous novel.

The second story, “How to Kiss a Hojacki,” also introduces a sci-fi conceit that repeats in the collection. In this story women transform into “Wonderfuls” — “Hojackis,” “Smith-Smiths,” or “Tangers” — asexual beings who must fight for their autonomy against a reactionary Trumpian politician who campaigns on interring them in camps.

“Hojacki” hovers around the viewpoint of a husband who is becoming increasingly resentful and sexually frustrated with his changing wife. He is unwilling to even try to redefine love: “having sex is how people love each other,” he contends. “Hojacki” is most fascinating when set in context against the stories at the back end of Portalmania, which deal far more directly with themes of asexuality, sexual coercion, and marital rape. While it would be a stretch to say Urbanski depicts the husband sympathetically, her rendering is nevertheless nuanced enough to be later deconstructed in far more visceral detail in stories like “The Dirty Golden Yellow House,” “Hysteria,” and “Some Personal Arguments in Support of the BetterYou (Based on Early Interactions).”

“The Dirty Golden Yellow House” is the strongest piece in Portalmania. It rewrites “How to Kiss a Hojacki” (and reimagines Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wall-Paper”) from the perspective of an asexual writer trapped in a marriage marked by marital rape and emotional coercion. “Yellow House” combines elements of fairy tales and Gothic horror with the more prosaic forms of the essay and the internet forum to yield a harrowing story. “Yellow House” also quickly registers as a metatextual tale, a self-deconstructing narrative that pauses early to take would-be critics to task:

Certain reviewers and readers have already started complaining about my recent stories, both their thematic similarities and their very specific view of relationships. I have examples. From one reviewer: Other than the overt political addition to the obvious social metaphors which helps extend this to novelette length, this [one of my stories] is exactly like the same author’s [another one of my stories] in being an overlong underplotted offputtingly narrated story of a repugnant asexual wife and a repugnant husband and their repugnant relationship. From another reviewer: It [one of my stories] is probably sending a message about something—menopause maybe?… I have no clue what the ending is supposed to mean.From a reader: My takeaway is that the story [one of my stories] was an exercise in catharsis for the author, and has no real value as a morality tale beyond—

My past self slams her (our?) body against the window glass. Has she not been clear enough. Here is what she expects in my writing: revenge, on me, on him, on them, on the structure of the story itself, and if I ever consider not placing her at the bloody heart of whatever I write, she will do this to me. She acts out what she will do to me. There is so much blood.

Angry, self-aware, and emotionally scorching, “Yellow House” nevertheless offers sparks of mean humor. The narrator observes that her “neighbors staked colorful rainbow signs into their front yard: WE BELIEVE LOVE IS LOVE AND KINDNESS IS EVERYTHING.” While the sentiment of the sign might be progressive, the tautology “love is love” is reductive and unhelpful in a book where redefining what love is is the (de)central problem.

Another highlight of the collection is “LK-32-C,” a triptych of stories about a troubled child’s fantasy world. (We might count “LK-32-C” as three stories, not one; each section has its own title.) The narratives in “LK-32-C” seem to run in concurrent yet divergent directions, where fantasy punctures reality or vice versa. In one such topsy-turvy moment, a distraught mother dreams up a magical totem of familial security: “if anyone questioned whether or not there was some love here, she could have pointed to that sphere.”

And again, in “The Portal,” fantasy punctures reality and metatextuality punctures the narrative. Our narrator interrupts building her fantasy world to tell us that,

I do realize that, as an author, I’m not supposed to let my other worlds become utopias. At least, that was one successful writer’s advice to me when I told him I was working on this story. He explained that when portal worlds are utopias, it’s like a flashing neon sign that says lazy writing. If we want such fantastic places to be believable (and who doesn’t want their writing to be believed?), they have to possess a substantial dark side.

Our author-hero’s rejoinder points out that the dark side is the absence of the utopia: “What if I’m trying to create an untroubled and pleasant world that might haunt someone for as long as they could remember it?” We’re always looking for that perfect portal.

Not everything in Portalmania works. “How to Kiss a Hojacki” has a great premise but its collapse into a political satire is dissatisfying. “Long May My Land Be Bright” is the weakest link in the collection. Its central conceit is that there are literal rifts in the USA, which create two separate antithetical political-cultural realities. It’s not that I’m not sympathetic to the sentiment here, it’s just that I think the metaphor should be pushed even further, to more absurd places.

I’m also not sure how I feel about Urbanski’s decision to include a tenth chapter in her book titled “Story Notes.” By the time I got to the (ostensibly)-last story “The Portal,” I was having a really hard time keeping all the New Criticism, death-of-the-author, grad-school reading training stuff out of my head. With its constant metatextual interruptions and its deeply– personal themes, it became very, very difficult not to read Portalmania as in part a work of autofiction. So the notion of “Story Notes” both intrigued and repelled me. Here is how “Story Notes” begins:

One of the indisputably vital roles of the modern reader is to tease out what is autobiographically true for the fiction writer versus what that writer made up in their stories. What is fiction after all if not a porthole into the author’s private life? So allow me to get this out of the way: Everything you’ve read in Portalmania (or will read, depending on your preferred order) actually happened to me. The portals, the lack of portals, the witches, the monsters, the ghosts, the murders, the space travel of beloved family members—every story in this collection is a factual account of my own experience. And now that you know this, I can spend the remaining space of these notes discussing whatever I want.

And I suppose she does discuss whatever she wants in the notes.

If we are counting “Story Notes” as a story, there are ten stories in Portalmania. If we keep reading after “Story Notes,” there is a final piece, “Coda” an unlisted hidden track of sorts. I love the decision to put this last, brief, and strong piece after “Story Notes.” “Coda” revisits the themes of Portalmania and concludes by pointing to “a terrifying and wide-open future,” which is what I suppose we can all expect as we fumble toward our own redefinition of love, storytelling, and escape. Good stuff.