In his 1992 interview with The New York Times, Cormac McCarthy said, “The ugly fact is books are made out of books. The novel depends for its life on the novels that have been written.” McCarthy’s masterpiece Blood Meridian, as many critics have noted, is made of some of the finest literature out there–the King James Bible, Moby-Dick, Dante’s Inferno, Paradise Lost, Faulkner, and Shakespeare. While Blood Meridian echoes and alludes to these authors and books thematically, structurally, and linguistically, it also owes much of its materiality to Samuel Chamberlain’s My Confession: The Recollections of a Rogue.

In his 1992 interview with The New York Times, Cormac McCarthy said, “The ugly fact is books are made out of books. The novel depends for its life on the novels that have been written.” McCarthy’s masterpiece Blood Meridian, as many critics have noted, is made of some of the finest literature out there–the King James Bible, Moby-Dick, Dante’s Inferno, Paradise Lost, Faulkner, and Shakespeare. While Blood Meridian echoes and alludes to these authors and books thematically, structurally, and linguistically, it also owes much of its materiality to Samuel Chamberlain’s My Confession: The Recollections of a Rogue.

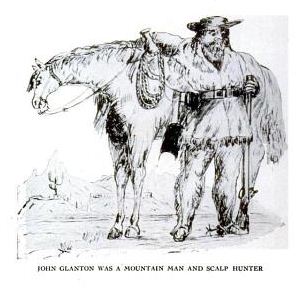

Chamberlain, much like the Kid, Blood Meridian’s erstwhile protagonist, ran away from home as a teenager. He joined the Illinois Second Volunteer Regiment and later fought in the Mexican-American War. Confession details Chamberlain’s involvement with John Glanton’s gang of scalp-hunters. The following summary comes from the University of Virginia’s American Studies webpage—

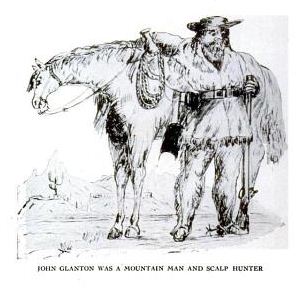

According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

Chamberlain’s Confession also describes a figure named Judge Holden. Again, from U of V’s summary–

Glanton’s gang consisted of “Sonorans, Cherokee and Delaware Indians, French Canadians, Texans, Irishmen, a Negro and a full-blooded Comanche,” and when Chamberlain joined them they had gathered thirty-seven scalps and considerable losses from two recent raids (Chamberlain implies that they had just begun their careers as scalp hunters but other sources suggest that they had been engaged in the trade for sometime- regardless there is little specific documentation of their prior activities). Second in command to Glanton was a Texan- Judge Holden. In describing him, Chamberlain claimed, “a cooler blooded villain never went unhung;” Holden was well over six feet, “had a fleshy frame, [and] a dull tallow colored face destitute of hair and all expression” and was well educated in geology and mineralogy, fluent in native dialects, a good musician, and “plum centre” with a firearm. Chamberlain saw him also as a coward who would avoid equal combat if possible but would not hesitate to kill Indians or Mexicans if he had the advantage. Rumors also abounded about atrocities committed in Texas and the Cherokee nation by him under a different name. Before the gang left Frontreras, Chamberlain claims that a ten year old girl was found “foully violated and murdered” with “the mark of a large hand on her throat,” but no one ever directly accused Holden.

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

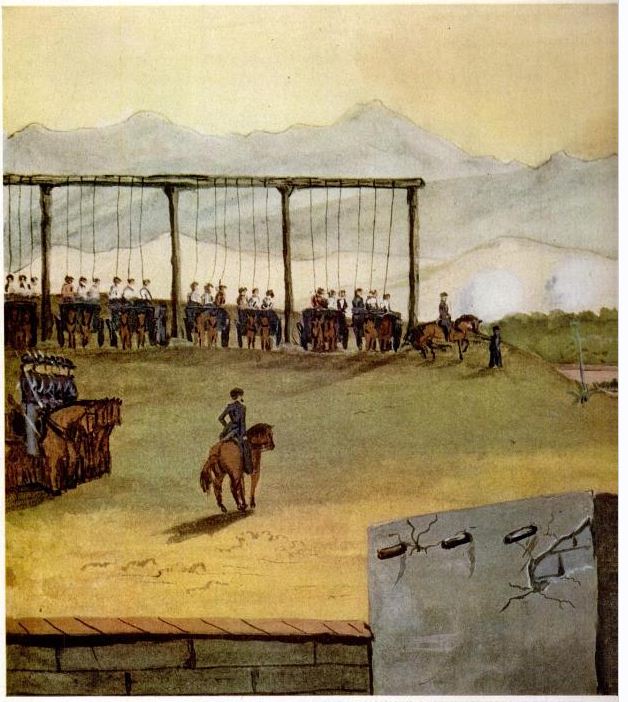

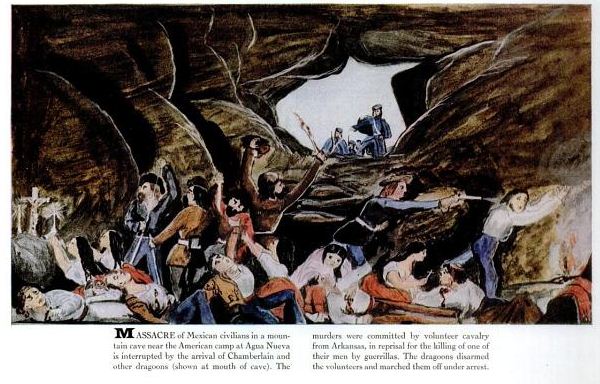

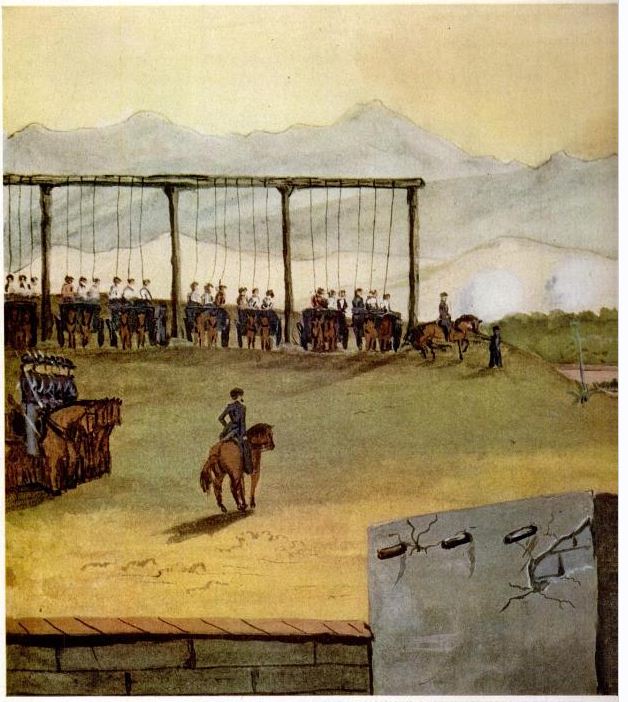

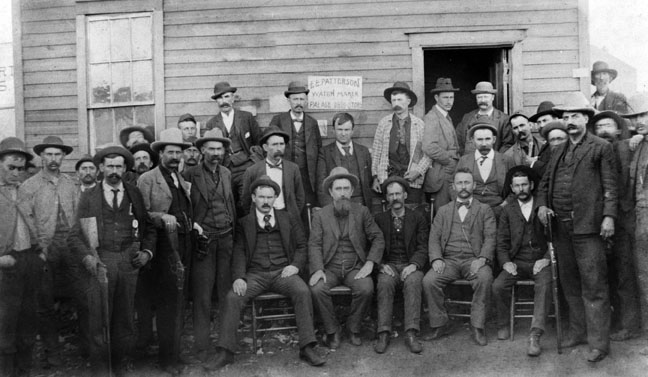

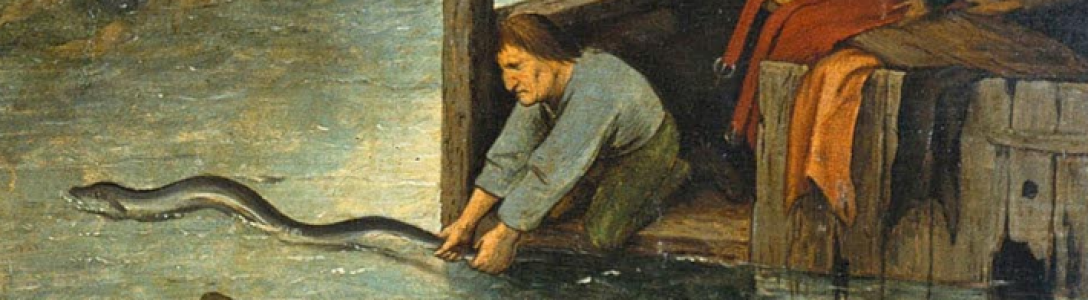

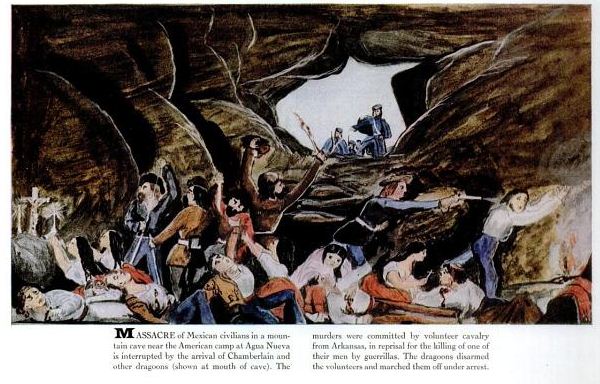

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book Different Travelers, Different Eyes, James H. Maguire notes that, “Both venereal and martial, the gore of [Chamberlain’s] prose evokes Gothic revulsion, while his unschooled art, with its stark architectural angles and leaden, keen-edged shadows, can chill with the surreal horrors of the later Greco-Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico.” Yes, Chamberlain was an amateur painter (find his paintings throughout this post), and undoubtedly some of this imagery crept into Blood Meridian.

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book Different Travelers, Different Eyes, James H. Maguire notes that, “Both venereal and martial, the gore of [Chamberlain’s] prose evokes Gothic revulsion, while his unschooled art, with its stark architectural angles and leaden, keen-edged shadows, can chill with the surreal horrors of the later Greco-Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico.” Yes, Chamberlain was an amateur painter (find his paintings throughout this post), and undoubtedly some of this imagery crept into Blood Meridian.

You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s Part I, Part II, and Part III. Many critics have pointed out that Chamberlain’s narrative, beyond its casual racism and sexism, is rife with factual and historical errors. He also apparently indulges in the habit of describing battles and other events in vivid detail, even when there was no way he could have been there. No matter. The ugly fact is that books are made out of books, after all, and if Chamberlain’s Confession traffics in re-appropriating the adventure stories of the day, at least we have Blood Meridian to show for his efforts.

You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s Part I, Part II, and Part III. Many critics have pointed out that Chamberlain’s narrative, beyond its casual racism and sexism, is rife with factual and historical errors. He also apparently indulges in the habit of describing battles and other events in vivid detail, even when there was no way he could have been there. No matter. The ugly fact is that books are made out of books, after all, and if Chamberlain’s Confession traffics in re-appropriating the adventure stories of the day, at least we have Blood Meridian to show for his efforts.

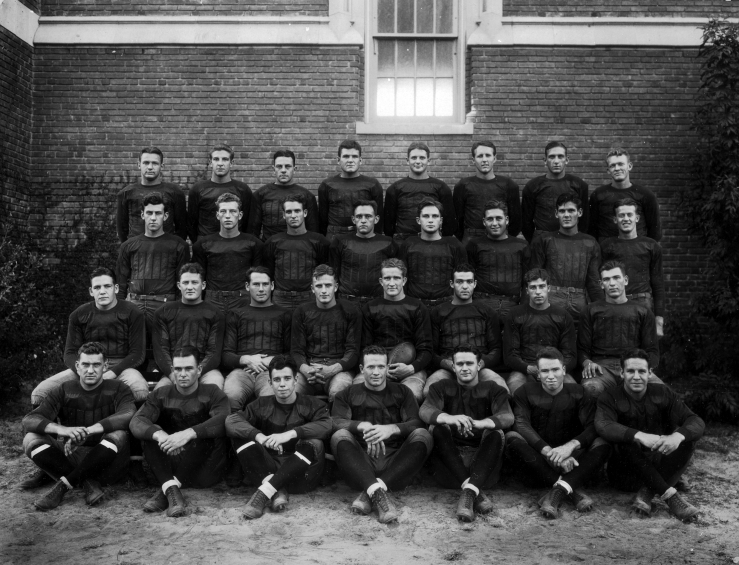

The romantic myth of the Western outlaw still remains central to American identity. If we are part Puritan, we also like to think of ourselves as the kind of anti-social cowboys who go out and manifest our own destiny. It’s no wonder that we have a tradition of valorizing outlaws like Billy the Kid, the Dalton gang, and Frank and Jesse James, transfiguring their bullying and theft into a kind of partisan resistance to hegemony. These men did not steal from the rich to give to the poor, yet we like to pretend that they were Robin Hoods. Turner Publishing’s new collection Historic Photos of Outlaws of the Old West presents 200 archival images of infamous (and not so famous) robbers, road agents, and rascals in the kind of gruesome detail that outlines just how awful these people really were. The Old West isn’t so romantic after all.

The romantic myth of the Western outlaw still remains central to American identity. If we are part Puritan, we also like to think of ourselves as the kind of anti-social cowboys who go out and manifest our own destiny. It’s no wonder that we have a tradition of valorizing outlaws like Billy the Kid, the Dalton gang, and Frank and Jesse James, transfiguring their bullying and theft into a kind of partisan resistance to hegemony. These men did not steal from the rich to give to the poor, yet we like to pretend that they were Robin Hoods. Turner Publishing’s new collection Historic Photos of Outlaws of the Old West presents 200 archival images of infamous (and not so famous) robbers, road agents, and rascals in the kind of gruesome detail that outlines just how awful these people really were. The Old West isn’t so romantic after all.

Stephen Kotkin’s Uncivil Society earned

Stephen Kotkin’s Uncivil Society earned  In his

In his  According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book  You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s

You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s