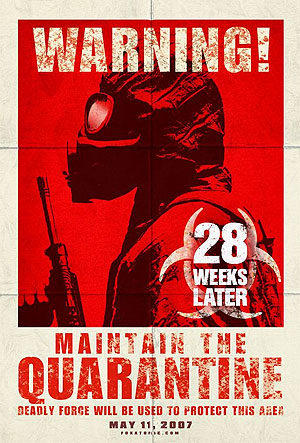

As that most sacred of holidays, Halloween, draws closer, Biblioklept begins our annual celebration with a review of 28 Weeks Later, the sequel to future cult classic 28 Days Later. Look forward to all kinds of horror for the rest of the month!

At Sam Kimball’s talk at UNF last week, he put forth several ideas that would not be wholly unfamiliar to students and former students of his, or to anyone who’s read his book, The Infanticidal Logic of Evolution and Culture. Just a few of these ideas: cultural and biological evolution rests on an encoded infanticidal threat that no one wants to own up to, existence costs, and the ability of humans to smile represents a Darwinian miracle. The first two of these ideas provide an excellent lens from which to examine 28 Weeks Later; however, I’m not going to strain myself looking for smiles or hope in this awfully bleak, absolutely horrific movie.

It’s instructive to begin with a paraphrase of the infanticidal logic Kimball suggests underpins social order, and I think that can be done best by using Kimball’s own re-reading of the Oedipus story. The story of Oedipus, who outwits the Sphinx, kills his father, marries his mother, brings a plague to his city, and then stabs out his eyes, is–and here comes an understatement–a story foundational to psychoanalysis. In most readings, Oedipus is the tragically flawed hero who brings shame, disease, sin, and death to an entire society through his multiple transgressions. Kimball points out that most readings of this story focus on Oedipus’ relationship with his mother and father (sex and death), and that little attention is paid to the very beginning of the story. Recall now that the infant Oedipus is cast by his royal parents (metonymy for all parents), feet bound, into the wilderness to die, for fear that he will bring about chaos and death. The story is thus initiated in an infanticidal gesture, the willingness to kill a child for the good of the family, the tribe, the kingdom (see: Abraham and Isaac, Saturn gobbling his kids, Noah and flood, the crucifixion of Christ, etc. etc. etc.). Kimball sees structural infanticide as the blame for sin and corruption and death being put on the child; Oedipus is not the sinner in this reading, but the one who has been wronged from the beginning. Let’s see if we can’t apply some of this to a zombie flick. And, uh, a SPOILER WARNING is in order, I suppose (although I don’t think anything I’ll write can really spoil this film).

28 Weeks Later opens up with a last supper, the communion of a childless, makeshift family who’ve managed to avoid the infected zombies that plague Britain, spreading murder and chaos wherever they go. The communion is interrupted by a child who bangs on the door. After some indecision, he’s admitted by the wary adults, who ask him, of course, “What happened?” “My parents…they tried to kill me,” he answers. Within minutes of his arrival, the zombies are at the door, ready to spread their infection, annihilating the dinner party: the child, on the run from his infanticidal parents, brings disease and death to the community. Only Don (Robert Carlyle) escapes, and he does so by abandoning his wife, who clings to the newly arrived child.

Twenty-eight weeks later, the US military has quarantined part of London, and begun the repatriation of British citizens, including Don’s son and daughter, Andy and Tammy (played by the improbably named Mackintosh Muggle and Imogen Poots). Chief medical officer, Major Ross is deeply upset when she sees the children disembark the plane, declaring that the Green Zone the US military has established is not equipped for kids. Furthermore, she points out that they know little about the disease, and that kids might actually facilitate spreading it. Sure enough, Andy and Tammy run away from the Green Zone, heading back to their apartment, where they find Mom, who’s gone feral. Their Mom has some kind of genetic resistance to the effects of the disease (figured in her mismatched brown and blue eyes, a trait shared by Andy); she exhibits mild symptoms and is a carrier. This is discovered by Major Ross when the trio are forcibly returned to the Green Zone. Don, swamped in guilt, sneaks in to see his wife. He kisses her, immediately gets the disease, then goes on a murderous rampage. The US military, in a moment of shining brilliance, move all the non-military personnel to a locked basement. Don gets in nonetheless, the infection spreads like a dirty rumor, and the army begins killing everyone indiscriminately. Again, the children bring the infection to the community, and the entire society must pay with wholesale apocalyptic genocide, ultimately figured in the firebombing of the city.

Andy and Tammy escape this fate when Major Ross and Sergeant Doyle, a kindly sniper, escort them out of the city. Ross and Doyle symbolize a set of “good parents,” in direct opposition to Don, a rampaging zombie who somehow singles out his children in particular. Just like the child at the beginning, the two are on the run from not just the patriarchal US army “protectorate,” now annihilating everything that moves, but also their own biological father. In the course of aiding the children’s escape, both Ross and Doyle meet grisly yet heroic ends. Believing that the children may carry a genetic clue to a vaccine for the virus, the “good parents” give their own lives to save the children. Still, the children are the cause of their death. Don eventually catches up with his kids and bites Andy, before he’s shot to death by Tammy. Andy, like his mom, doesn’t go nuts when he gets infected, but he’s still a carrier. Doyle’s buddy, helicopter pilot Flynn, transports the kids across the English Channel (that is, after making the tough decision not to just kill them). The movie ends with shots of rampaging zombies near the Eiffel Tower: a child has again carried infection, disease, and death to a once-pure, contained area, continental Europe.

Upon its theatrical release earlier this year, most critics focused on 28 Weeks Later as an allegory of US military involvement gone awry, a thinly-disguised critique of the Iraq invasion. And while many arguments could be made for this analysis, I think its important to realize that the actions of the US military in the film are not ultimately the cause of the apocalyptic genocide at its center; rather, the military responds appropriately to contain the very real threat of contagion, the risk of total death figured in the disease the zombies carry. The cost of continued existence here is the realization that everyone in the Green Zone must die. The movie invites us to see both the military and the zombies as the bad guys, but ultimately the movie blames the children for the downfall of mankind: the army is just trying save the rest of the world, making a calculated cost analysis (albeit, one measured in human lives); the zombies are, well, uh, mindless rampaging zombies–animals, running ids with teeth, but not really evil. No, it’s the kids here who bring about sin and shame, death and disease. The infanticidal structure of the film argues for the execution of children, those dirty little harbingers of contagion. Paradoxically, the film hides this gesture under the heroic self-sacrifice of the “good parents,” Ross and Doyle, who give up their lives to save the kids. The audience is invited to empathize and identify with Ross and Doyle, who reject both the patriarchal authoritarianism of the US military (despite the fact that they are both military officers) as well as the mindless entropy of zombism. In the end though, their self-sacrifice is pointless–Andy spreads disease into another “pure” area, putting the entire world at risk. Flynn should have executed the children, like he was supposed to. The movie thus acts as a warning against the dangers of sin and infection that are presented in the children, and in turn, 28 Weeks Later upholds patriarchal, sacrificial, infanticidal values.

In my ranting and raving and raging and rampaging, I forgot to point out that I enjoyed the movie very much: it was truly terribly awfully bloodily unceasingly horrific.