, , – , – – ‘ – . , , – , . ” ” . , – , . . , , – ‘ ( ) , . . ; , . ; , , . , , . . – – , , – – . . , – – , , , , , , – . , . . . ; ; . – – , , – – , ” , ” ” ” , . , , . . , , , , . , , , , – , , , – , . ‘ , – – – , . . . ; , , . , ‘ – . . , – , , . ‘ , ‘ , . , , . , , . , – – ” . ” – – – – , – , . , , , , , – – , . , . , , . , , . . , ‘ , , ‘ , , , – , . – . ; , , , . ‘ . , – . , , , , , , . , ; : ” , , ‘ . ” ” , , ” , ; ” , . . ” ” , ‘ , . . , – . , , . . ; . ; , . ; , – . , , , ‘ , ‘ , – , . – – , , – – . , – , – – – – . . , . , . , , . , , – – , . . ‘ , ; . ; ‘ . , , – – . , , – – , , . , , ‘ ; ! ” . ” , ” , ; ” , , ! – – – – – , ” ‘ . ” ! ‘ , . , . ; ; , , , , . – – ‘ ? , ” ‘ , ” ; , – – – – ! – – , ” , ” ‘ – . – . , . , – – ‘ . ” . , , – – . – ‘ ; ‘ . – ‘ . ‘ , , , , , , , . , ‘ , – – , – – ; , , – . , , ” – , – – . ” ” , ! ” , , . , ‘ . ; . ‘ , , . , , , , , ‘ , , , . . . , . , , , , . , , , . – – – . , – – . : ‘ ; , – , . , ; , , , , , , . – , ‘ , . ; , , , , , , . , – ; . , , , , . , ‘ – . . – . – . . , , . . , , , , – ‘ , – ; , , , , ; . – – – , , . , , , , , ” , , ‘ . ” ” ‘ ? – – ? ” ” , . ” , , ” ? ” ” , . ‘ . ” ” ? , ” ; ” , . ‘ , ; . ” , , – , , , . . , , , , . ; , , . – , ‘ . , , , – , , ” ‘ – , ” . , ” ‘ – , ” ? ; , , , ; . , , . ‘ , , , , , ‘ . – , , , . , , , – ‘ , , , : – – ” , , , , ? ” ; , ‘ , . , , ; , . , – , , , , , . , , . , , – – . , . ‘ . . – , ‘ , , , . , . . . , , . . – . ; – – – – – , – – – , , ; , ‘ . , . – – – – – , , : ” , ‘ ‘ ! ” ‘ ; ( . . . ) ” . ” , . . , , . , . – , . , , – – – – , ; , , – – – – . , , ; . , . , – – , , , – – , . , , : , , , , . , , – . – . . , . – . – , , , , , . , , ‘ , , , , , , , , . , , , , ‘ , , , , , . , – , . , , , , ; , . , ‘ – , ‘ , , , . , , ; ; ; , , , , , . , , . – – . , , , – – , – – . ; , , , . , . , ‘ ” . ” , , , . , ; , , , , . , . . , , , , , , , , . , , , , . , , – , , , ; , . , . , . : , , – , , ; : , ; , , , , , . – . . . , , , . – , . , . , , , . , . , , , ; , , . – ‘ , – . , , , , . , . , , , , ‘ , ‘ – , . , , . ‘ , , , . – – , , . ; . – – . , , : , , – , ; ‘ , , , , , , , ” ‘ , . ” , ‘ , , , ” , ; , ! ” , ‘ , , , . , . – , . ‘ , , . . , , . , , – , . , ; – – , , , , , . – – , , , . . , , , , . , , . , , , , , . , : ” , . , ” ( ) ” . , ‘ ‘ ? , ‘ – ? ” ; ‘ , . , , . ‘ . , – . ‘ , – . – , . , . , – – . – . , , – ‘ , . , – – , ; – – – , . , , . . ; ; , ‘ , . . , . . ; , , – . , , , ‘ , . , , . . ; , . – – – – ‘ ‘ . , , . , , – – . ‘ , , , , ; , , ; . ‘ – – – , – , , – , . , – . , . , ‘ – , , . , , , , , , ; , ; , , . : – , , . . , ‘ , . , . , , ‘ , . . ‘ , . – , – – . , , , ; . ‘ – – ‘ ‘ . – , , – – – , – – . , , , , , , , – – ‘ , , . , , , ; – – . ‘ – , , , ; , , . ‘ , ‘ , , , – . – . , , , , ‘ , , . ‘ . , . . – . , , – , . , , , ; , . ‘ , ; ‘ , . . , ‘ – , . , ? , . . ” , ? ” . ” , , , ‘ . ” , . – , . , , . , – – , – . ; , , , , , ‘ . – , ‘ . , – , ‘ ” – – – – . ” – , . , , , – ‘ , ? , ‘ ; , , , – – , , ; . , . . . ‘ , , , , , , , . , , – ; , ‘ , , . . , , , – , – , . , . , ‘ . , , ” , , . ” , , , ” , ” ( – – – ) ” . ” ” ! ” , ; ” ? , . ” ” ? ” ; , ” , , . ” ” , . . . ” ” ‘ ‘ , . ” , , . ; – , , , . , – , . ‘ – – . , , , , , – . , – – , , , . , , , . . , , , , , , ” , ! ! ” . , , , , ‘ . . , ” , ” ; , , , ; , ” , ! ” ” , ? ” . , , – – – – , – – . , , , , ; – . , , , ” ! ” – – ? , , , , , ? – ‘ , ‘ ” ” ? , , ‘ , ? , , , , , . , , , ‘ – – – , , . . , , , , . , , , ? – . , . ‘ . ? , . ” . ” . , , , ” , – – – – ‘ . . , , – – – , , ” ” – – , . ” ” , ” , ” – – – , , , , . ” ” , , . , , , . , , , . . . . ‘ . . ? . ” . . , , , . , . , , : ” : . ” ‘ , ‘ . . . , , , . , , . . . . . . . , . . : ‘ , , . : , . , , , ; , – , , , , – – – – . , , , , ” . ” , , , ? , ? ? ? , , ; ; , , . , . , . ? ” ” ? , , – . – – . , , , . ‘ , , , , . , . ; ‘ , , , , . – . , – – , , , , , . , , . ? , , ? . , . , . ‘ . , , ‘ . ‘ . , , , , . , , , , , . , – – . , , – – . ! , – – , , . , ‘ ; , ; ‘ , , . , , . , , . , , . , – – – ‘ – ‘ . – – , – – , – – , ‘ . , , , , . ‘ . – , , , , , . ‘ – – – – – – – , , , , . – – , , – – , – – , – – ; ( ) . , ‘ . , . , ; , , . ; ? ‘ ? , , ” , ” . ‘ , , , , , , ; , . . . , – – ‘ ; – ; , , . , , . , . ; , , , . – , , – ‘ , , . , – ; , . – , , , , , ” , ; . ‘ . , ” ; . – – ; , , , , . . , . , , . , , , , , , – – ; , – , ‘ ; , , , , – , . . ; – . ‘ . , , , . ” ! , ” ; ” , ‘ ? , ! ” ; , . , , . : ” , . ‘ . – – – ‘ – – – – ? ” ” ? ” , . ” , ! ” , ” ” ; ; ” , , , ‘ – – ” , : ” – – – , ‘ – – , , – – ! ” , , ; , , ” – ‘ ‘ – – – ! ” – . ” , ‘ ? ” – ‘ . ; ” , , ? , – – . ” ” , ” , ; ” . ” ” , ? ” , – , ; ” ‘ ! ” . , ‘ , ‘ , , – , , , , , – , . . ; . , , , . ? , ? ? . , – , . ‘ , , . , . . , – , , . , , . – – – , ; , , . , . , , , , . ‘ , , , , , . , , – , , , , . . , . , – . , , , , – , . . , , ; , , , . , . ‘ , ; , , ” ‘ , ? ” ” ? ” . ” , . ” ” , ” , ” ? ” ” , . ‘ – , ‘ – ! ” , , , , , ‘ , ‘ , , , . . , ‘ – – , , ‘ , ” . ” . . , . , – . ‘ , . , , , . ; ‘ . , , , , . ? – , – – – , , , ‘ , . , . , ; , ; , , . , , . . ‘ . , , , , , . , , ; ; – – – , – – , . , – , , , – – – , ; . . , , , , , . , . ‘ – , ; – , . . , , . , , , , . , , , , . . , , . ‘ , . . – – . . , ” – . ” , , . , . . – – , , ; , . , ‘ , , ‘ – , , , , – – , . ‘ , – , , , . , ‘ , , ‘ – , . ‘ , , , . ( ) , , , . , – . , , ‘ . , . , , ‘ . , – – – – , – ; , . . – – – – – . ( – – ) , , . , , , , , , . , , , – . . ‘ , , . – , . , , – – , , – , – – , . – – – . – – ; , , , . , , ‘ , . ‘ – ‘ , , , – – . , . , , , . , , , , ” ? , – – ? ” , , , , , . , , , , , , , , ‘ . : ” , ; . ” , . ( ) , . , . , , , , , . , , . , ‘ ‘ . , . , , : ” , , ‘ – – ” ” ! ” , , , . . , – , . , – , . . , , . , – , , , , ‘ . , , , , , , , . . , ‘ – , , , , . : ” . . ” ” . , – ” ” , ” ; ” – – – – , ‘ , ‘ ? ” ” , ; , . , . ‘ , ‘ ‘ ? – . . – – . ” , , ‘ . ‘ , , . ‘ – – , , , , ‘ , ; , . ‘ , , ‘ , , ‘ – , , , . – – , , , . , ” ‘ , ” , ‘ . ‘ ” – , ” ‘ , : ” , – – , ? , . , ” , ” . , , – – – – . ” ” , ! ” , . , – – – – – , , , . , , . ‘ , ; . , – – – ‘ – – , – – , – . , – , – ‘ , , . – – – – . . , , , ‘ . , – – . , ; . , – . – , , ‘ – ; ‘ ; ‘ , ‘ ; ; , ‘ . , . , ” – – , ‘ ? ” ” , . ” , ” . ! ” , ” . ” ‘ – , – . . ” ? ” ” , . ” ” . . . . . , . . . – – – – , , , . ” , , , . . , ‘ . ‘ : , , , . ‘ . . – – . ” , , ” ; ” , . – – , – – – , ; ” . – , , , . . , – . . ‘ , , . , . ; – . ” , ! ” , ‘ , ” ! . ” ; ; , , , , – ; , , . ‘ , , ‘ . , , , ” , . , . ” , , ‘ , – – , . , , , . ‘ , , – – – ; , . , . ” , ” , ” ! , . ” . , . . . . , ? ; . , , . – ( ) , . . – – , , ” . ” . ” , ” , ” . . ” – – – , – – , , ‘ , , ” , , ” . , – , . ‘ , . ‘ . ” ? ” . ” . . ” ‘ , , . , , . , ‘ , , – – ” ! ! ” ‘ , , , . . , – – ” ! ! ” , , . , . ” ; , ” , ” ” ( ) ” , ” . , , . ” , ” – – ” . – . , . , ” , ” . ” . , , ? – , , . , , , , . . ? , . ? , , . . . ; ‘ . . . ? , ? . . , , ‘ . . , , , . . , , – – – . . , , . ; , , . . , , – . ‘ , , . , ; , , , , . . , , – , , , . . , , – ; . ‘ , . . – . , , , , . ‘ , ‘ . , , . , , , , . – – , , , , . – , . , , . , , , , , ‘ . , , , . . , ‘ , . , , – ; – , , ‘ . – . , , , , , , , ‘ – , – . , ‘ . , . , , , ” . ? ” . : ” . , – – . ‘ . ” ” , , ” , . ” , ! ” , . – , , ” , . – – . . . . , , , ! ” – , , ‘ – – ‘ , ” , . ” ( , ‘ ) ‘ . . . ; ‘ – . ‘ – – – – – , , ; , , , . . ” , ” . ” – – . , , ? ” ‘ , , , , . , , . , . ” . ? ? , ” . ” . , ‘ , , . – – , , ‘ , ‘ . ” , , , . , . , ‘ . . ; : ” – – ‘ , – – , , . ” ” , ” ; ” . , ; , , ‘ , ‘ . ? – – – – – , ” . ” ‘ , – – . ” , , , . , , , . , ” , ” , , ” , , . ” ; , , , , ” , . ” – – – – – , – – , , . , ‘ , . , . , , , – . ‘ , , . , – – ; , ‘ ; . . , – , . . , , . , , , ‘ . : ” , ; , , , , – – – – , , , – – – . , ? , . , , . , . , , . ” : ? . . : ? , , – – ‘ , ? ‘ ? – , ? – – ? . , , . . ? , . , , ‘ , ‘ ? , – . ? . , . . . . ? , . : , . ” . . . ? , ‘ , . ” , ; . ” , , . , , ? ” , . , ; , . ” , . – – – – – ‘ – , . , , , . – ” ” , , ” , ” . . ” ” , . , . . ? . – – . ‘ – – – – . , . ‘ – , , ? . . ‘ , , . , . , ‘ , . ‘ – . ” , , – – – – . ; – – . ” ” ? ” , , . ” , , . , ” ( ‘ ) ” – ; ; ? – – – – , . , ‘ , , . , . . ? . . ? . – – – . . , – – . , . , , , . , , . . , . ” , – , . ‘ . , , , , , , . , – , , – – ‘ – ‘ . . . – – , – , , – . . . , . , . , – , . , ” – . . , . , ‘ . – . ” , – , . , , . – , – – – – – . ; . . – , – – – – . – – , . ‘ . ‘ . , . . . ‘ . , , . , , , ‘ . , , , , . . , , , ‘ , . ‘ . , , . , ; , . ‘ – – ; , ; – – . – , , , . ; , , – – . – , ; – , . . ; – – ; ; . . , . ‘ ‘ . , , . . , , , . ‘ – . , , , – – . , . , , ‘ , , – – – ‘ – , . , , . ‘ – – – . , . ; ‘ . . . – – . ; , – , ‘ , . ‘ , , , . . – . , – – – , , ; , , . ‘ , , , ‘ . . , , – . – ( , , ) , ‘ . , – , – . . – , . . – . – , ‘ . , , ‘ , ‘ – – . . , . , – , . ‘ , . , , , , , , ‘ , . . , , , , , . , . , ; , . . , , – . , , ; , , , , . , , , , ( – ) , , , , , ” ” ( ) ” ? ? ” ‘ , , – . , , – ; . , ; – – . – – – ‘ . , . . ‘ . . , ; , ; , . , – , , ; . ‘ ( ) . , , . , – – . , . ? ; . , – , , – – – . , , . , . . , . ‘ . . , , – – , – – . – , – , . , , . – – , – – – . – . , – . , – . – , . , . , . ‘ , . . , , , – – ” ! ” – – – ‘ ; – , , ‘ . , ‘ , – – ” ! ” , . , , ‘ – , – ‘ . , , , . , ‘ , , , ; , , . , – , , ‘ , . , , , , ” – , ” – – , , , , ” , . . – – ‘ – – , . – – – – . ” ” , ? ” ” , . . ” ” , , ? ” ” . , . – , . , , . ‘ , , – – , – – , ? ” ” . ” ” , . , . ” ” , , ” , ” ‘ , ? ” ” , . , – : – – – . , – – , . , ” , ” – . , . ” . , ‘ , . – , ; , . – , ‘ . , , ‘ ‘ . , . ” , , . ” – , ; , . , – – – . – , ‘ . , ‘ , , – , – ‘ , . . . , , – , , . , – . , – , . , – – ‘ – ; – , ‘ , . , . . , , . . – , . , , ‘ . , – , ; , . , , . , , . ” , ” , ” , ; – . ” . , . – . ‘ . , , , , . . – , . – ‘ . . ; . . ‘ , . . – , . – – . , , , ‘ , , , – ; , ( ) – . – , . ; , , – – ‘ . – . . , . , . , . . , , . , , – – ” , . ” , ‘ , – , , ‘ , . , , , , . , ‘ , , , . : – – ” . . . . , ‘ – – , ‘ , ; , , – . ” , ‘ , . ” , , – , , – , , , ‘ . , & , . , , , . , . ” . . . . . . ” , , . . . , – . – – , – . . ‘ , , . , . , . , , , , , , ; , . ‘ . – ‘ , . – – : – ! ‘ ; ‘ ‘ . – ‘ – , – – – – – , ‘ , ‘ . , , , ; , . , , . ‘ – – ‘ . , ; , , ! . – – ‘ ? ‘ ; . ? ? , ? ; ‘ . – – ! ‘ , . . . ‘ , . , , ‘ . . , ? , , , .

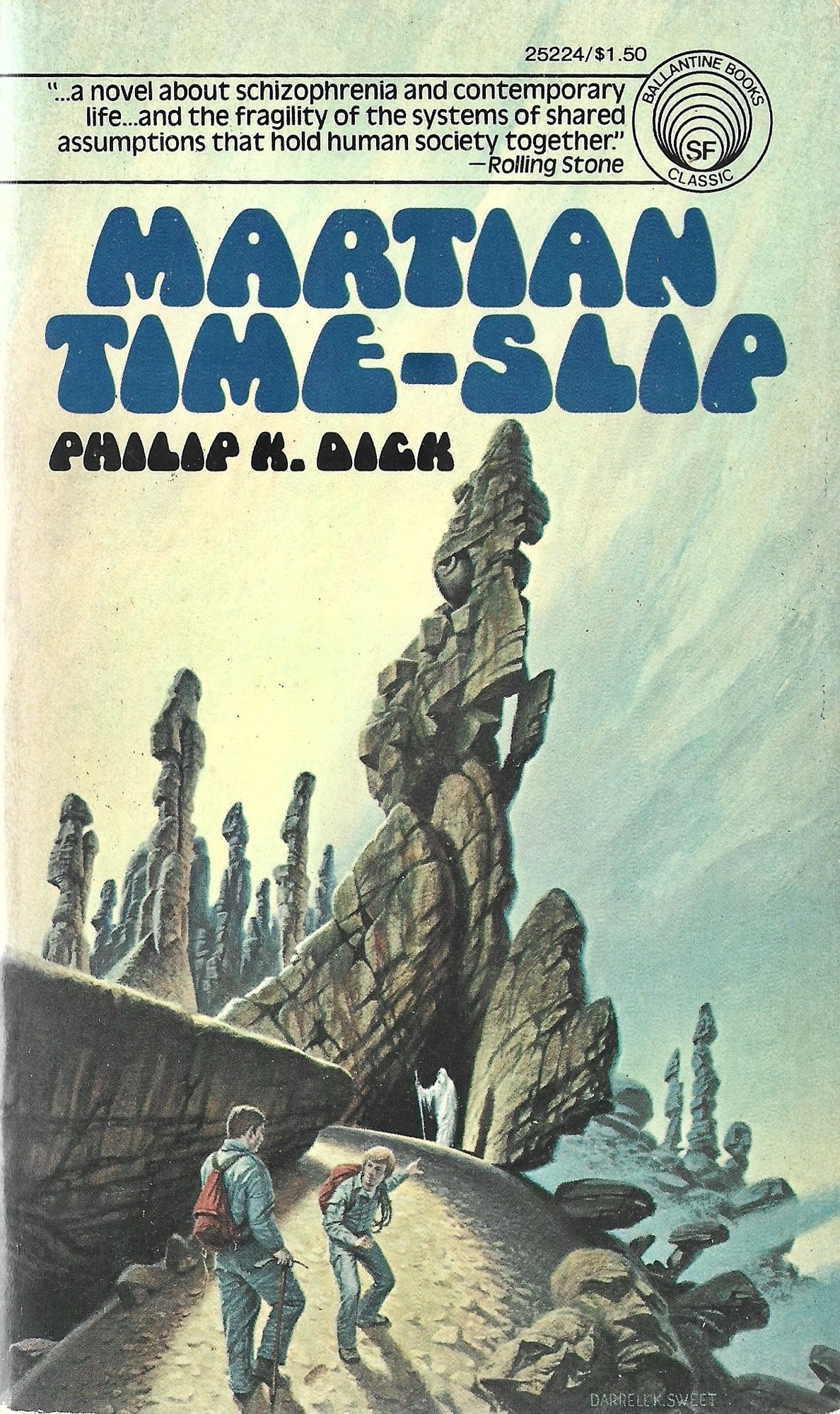

Martian Time-Slip, Philip K. Dick. Ballantine Books, second printing (1976). Cover art by Darrell K. Sweet. 220 pages.

Martian Time-Slip, Philip K. Dick. Ballantine Books, second printing (1976). Cover art by Darrell K. Sweet. 220 pages.