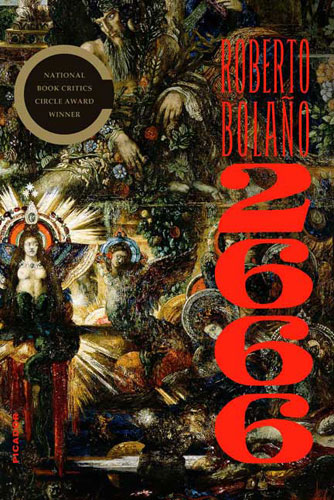

Any bibliophile can attest that one of the greatest pleasures of re-reading a favorite book is that it doesn’t change. You change, but it doesn’t, and somehow, you can measure your own change against it. So when Picador’s new single-volume trade paperback edition of Roberto Bolaño’s magnum opus 2666 (out today) showed up at my doorstep a week or two ago, I was thrilled. I already own the book, but having another copy of it, for some reason–no logical reason, of course–seemed really important. It also puts 2666 in good company: I own two (or more) copies of Moby-Dick and Ulysses, and I’ve had to buy at least three copies of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (damn biblioklepts don’t return books). I bought FS&G’s triple trade paperback edition of the book at the end of last year, and I loved it loved it loved it (review here if you don’t believe me). So how does the new single-volume edition differ, you ask? Well, first off, it’s important to note the gracious similarities–Picador’s edition retains the same pagination, a trend that I hope will always continue with this book (editions of Infinite Jest have managed to keep cohesive to date as well). The new trade paperback is surprisingly supple and portable, with wider margins than the FS&G triple-job. With more room for marginalia in the cohesive package of a single volume, Picador’s edition will likely be the go-to for scholars and book clubs (it’s also about half the retail price of the FS&G editions, but just as attractive).

So, anyway, why should you read 2666 if you haven’t already? I’m going to be lazy and refer again to my original review, but I’ll also be generous and direct you to Macmillan’s resource site for 2666. The site already has plenty of great links to full reviews and interviews with Bolaño, and Picador’s publicists have assured me that they will be updating the site frequently with additional content to aid readers, including artwork and images. Also really cool — the folks at The Morning News, who host Infinite Summer, the Infinite Jest reading project, will launch a similar site for 2666 on January 1st of next year. Even though I’m pointing out all of these resource sites, I think it’s also important to note that 2666 is an incredibly readable book. Which leads back to my current re-reading–and, hopefully, to an argument why you should re-read 2666.

So I bought my original copy in San Francisco last year, on vacation, and began digging into it on the plane ride home. I read most of Part I, “The Part about the Critics” in something of a dazed post-hangover travel stupor. I was familiar with Bolaño’s epic sentences from The Savage Detectives, but I instantly liked this book better. It also seemed to defy all of my expectations–wasn’t this supposed to be an unremitting catalog of horrific murders? Anyway, I got to that part later. Fast forward ten months or so. Again, I’m on a plane, again, coming home, returning from Las Vegas, more dazed, more hungover than before, and I pick up 2666, and again, I dig into Part I. The book is a different book. Lines that made me crack up before seem sinister. I see murder where I’d seen academic squabbling. But there’s also that hope, that possibility, that force of humanity that might be Bolaño’s signature rhetorical move, and I see it too now. Upon a first reading, 2666 might seem impossibly incomplete: a book that could never end, a book that would have to keep going. And it is. It’s a cycle; it returns to itself, a series of calls and responses far richer than can be puzzled out over one, or two, (or three, or four . . . ) readings. But best of all, it’s great, greater than before. What might have seemed a fortunate fluke of a forceful voice reveals itself to be profound and measured control–Bolaño’s themes are layered like a labyrinth, but what a joyful labyrinth to traverse! Re-reading 2666 on the plane was a strange echo, doubled in the myriad echoes that I found on my re-reading. I finished most of Part I (skipping occasionally into sections of Part V, and then Part III, and so on, liberated all of a sudden), and when I got home, despite the paramount exhaustion of a long Las Vegas weekend with a few dozen friends, I collapsed in my bed and into the book, not wanting to put it down, staying up far too late reading. Again. Great stuff. Go get it if you haven’t yet, and if you’ve got it, read it again.