A few years ago I posted a brief excerpt from Jules Siegel’s March 1977 Playboy profile “Who is Thomas Pynchon… And Why Did He Take Off With My Wife?” The excerpt came from an excerpt posted on the Pynchon-L forum, but most of the article had been removed at the (apparent) request by Siegel. A few people sent me the whole article though (thanks!) and I read it.

Jules Siegel was briefly a Cornell classmate of Pynchon’s in 1954, and they remained friends (in Siegel’s recollection) for at least two decades after. During this time, Siegel claims that Pynchon wrote him dozens of letters, which were ultimately sold at auction (along with much of Siegel’s property) to help pay for a hip replacement. Material from the letters soak into Siegel’s sketch of Pynchon’s progress, along with several stoned/drunken adventures that would not be out of place in V. or Mason & Dixon or Gravity’s Rainbow, or really, any person’s young life.

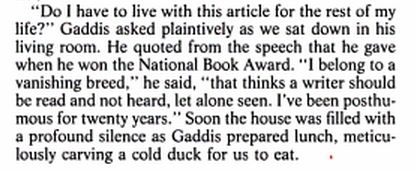

A competitive anxiety reverberates under the piece. “We were friends, maybe at some points best friends, very much alike in some important ways,” Siegel writes. “We were both writers,” he boldly writes. Siegel reminds us that “In Mortality and Mercy in Vienna, Pynchon’s first published short story, the protagonist is one Cleanth Siegel,” but protests he doesn’t see himself in that hero.

The competitive anxieties culminate in the big reveal that (spoiler!) Thomas Pynchon had an affair with Siegel’s second wife Chrissie. There’s probably a Freudian reading we can append to the details that Siegel offers about Pynchon’s sexual prowess: “He was a wonderful lover, sensitive and quick, with the ability to project a mood that turned the most ordinary surroundings into a scene out of a masterful film—the reeking industrial slum of Manhattan Beach would become as seen through the eye of Antonioni, for example.”

Or maybe these unsexy details are just a sign of Playboy’s editorial hand. Wedged gracelessly between ads for vibrators and nude greeting cards, Siegel’s lines often reek of 1970’s Playboy’s rhetorical house style, a kind of frank-but-(attempted)-sensual glossiness that contrasts heavily with Pynchon’s own sex writing. At times I found myself reading Siegel’s prose in one of Will Ferrell’s more pompous accents.

Even worse is the casual sexism of the piece—which again, may be attributable to Playboy’s editors. Siegel, on his first wife (sixteen when he married her): “She was so wonderful a lover, generous and easily aroused, but I was too callow then to appreciate her.” Of his second wife: “It is easy to underestimate her intelligence, but it is a mistake. She is obviously too pretty to be serious, conventional wisdom would have you believe.” Of one of Pynchon’s girlfriends: “Susan has red hair and is breathtakingly beautiful, with the voluptuous body of a showgirl. Like Chrissie, she is much brighter than she looks.”

More interesting, obviously, are the (supposedly) real-life details that inform Pynchon’s fiction. Siegel notes some of the contents of Pynchon’s Manhattan Beach apartment: “A built-in bookcase had rows of piggy banks on each shelf and there was a collection of books and magazines about pigs.” Pigs, of course, are a major motif of Gravity’s Rainbow. Another detail that seems to connect to GR: “On the desk, there was a rudimentary rocket made from one of those pencil-like erasers with coiled paper wrappers that you unzip to expose the rubber. It stood on a base twisted out of a paper clip.” Siegel lets us know that he knocked the rocket down. Pynchon puts it back together; Siegel knocks it down again.

(Parenthetically: Siegel’s evocation of Pynchon’s Manhattan Beach days fits neatly into my picture of Inherent Vice).

In accounting details of Pynchon’s alleged affair with his wife, Chrissie, Siegel shares the following:

Once, out on the freeway, she told him that we had all gone naked at the commune, he professed to find that incredible and dared her to take off her blouse right there. She did. A passing truck hooted its horn in lewd applause. He loved her Shirley Temple impersonations—On the Good Ship Lollipop sung and danced like a kid at a birthday party. They talked about running away together.

It is hardly possible here not to recall the episode early in Gravity’s Rainbow wherein Jessica Swanlake removes her blouse in the car on a dare from Roger Mexico. Is Siegel daring the reader to extrapolate further? Extrapolation, paranoid connections—isn’t this part of Pynchonian fun?

In that spirit, I’ll close with my favorite moment from the article.

“You know the W.A.S.T.E. horn in The Crying of Lot 49? The symbol of the secret message service? Every weirdo in the world is on my wave length. You cannot understand the kind of letters I get. Someone wrote to tell me that the very same horn was the symbol of a private mail system in medieval times. I checked it out at the library. It’s true. But I made it up myself before the book was ever published, before I ever got that letter.”

The lines are supposedly from Pynchon himself. Siegel even puts them in quotation marks—so they must be real, right?

[Ed. note: Biblioklept ran a version of this post in 2015].

The Guardian published a great

The Guardian published a great