Flight to Canada, Ishmael Reed

A frenetic, zany achronological satire of the American Civil War. I wrote about it here.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle, Shirley Jackson

Jackson gives us a quasi-idyllic-but-also-dystopian world delivered through narrator Merricat, an insane witch whom I adored. Merricat hates with beautiful intensity. The novel’s premise, prose, and mood are more important than its plot, which is littered with trapdoors, smoke and mirrors, and gestures toward some kind of greater gothic paranoia. It’s a slim novel that feels like 300 pages of exposition have been cut away, leaving only mystery, aporia, ghostly traces of maybe-answers.

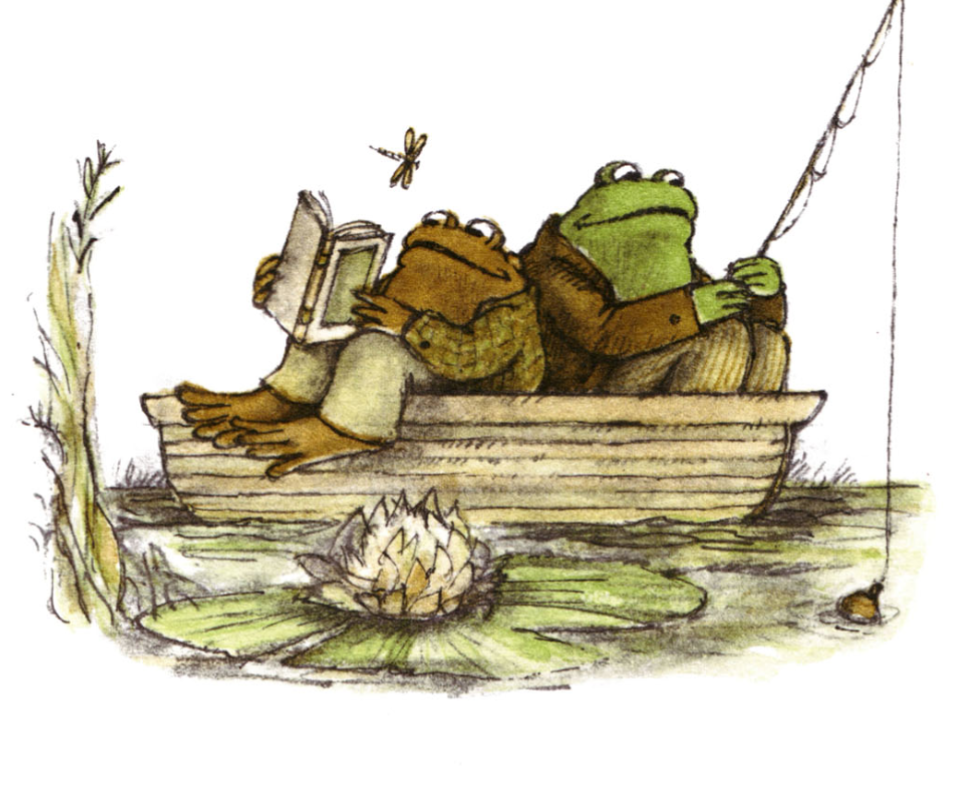

Titus Groan, Mervyn Peake

The first of Mervyn Peake’s strange castle (and then not-castle trilogy (not really a trilogy, really)), Titus Groan is weird wonderful grotesque fun. Inspirited by the Machiavellian antagonist Steerpike, Titus Groan can be read as a critique of the empty rituals that underwrite modern life. It can also be read for pleasure alone.

926 Years, Tristan Foster and Kyle Coma-Thompson

The blurb on the back of 926 Years describes the book as “twenty-two linked stories,” but it read it not so much as a collection of connected tales, but rather as a kind of successful experimental novel, a novel that subtly and reflexively signals back to its own collaborative origin. My review is here.

Anasazi, Mike McCubbins and Matt Bryan

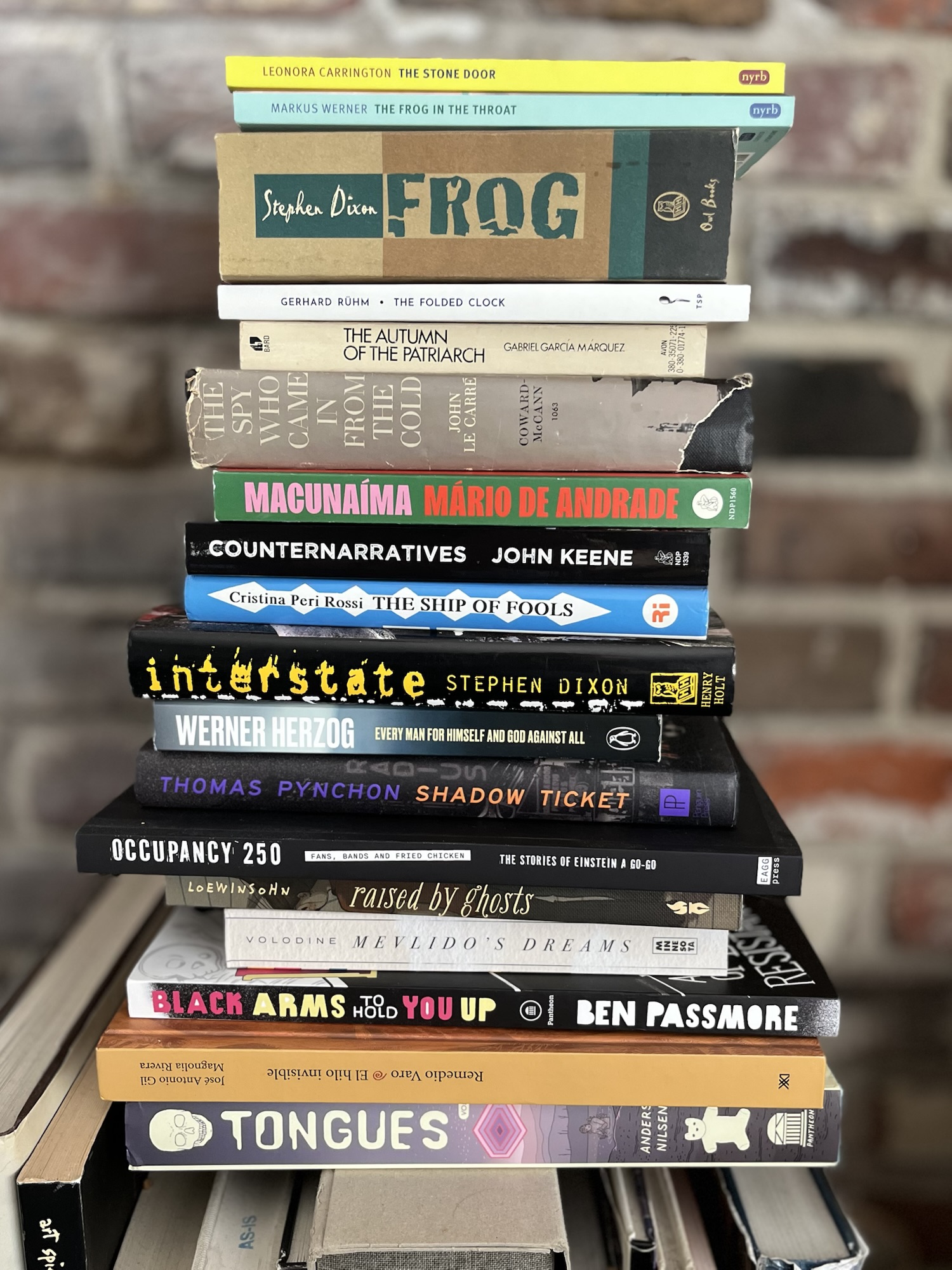

One of the best books I read (and reread) all year. The joy of Anasazi is sinking into its rich, alien world, sussing out meaning from image, color, and glyphs. This graphic novel has its own grammar. Bryan and McCubbins conjure a world reminiscent of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Martian novels, Charles Burns’ Last Look trilogy, Kipling’s Mowgli stories, as well as the fantasies of Jean Giraud.

Machines in the Head, Anna Kavan

I have a longish review here.

Machines in the Head was the first book I was able to write about after the onset of the Great Quarantine of 2020.

Gormenghast, Mervyn Peake

Probably the best novel in Peake’s trilogy, Gormenghast is notable for its psychological realism, surreal claustrophobia, and bursts of fantastical imagery. We finally get to know Titus, who is a mute infant in the first novel, and track his insolent war against tradition and Steerpike. The novel’s apocalyptic diluvian climax is amazing.

Gringos, Charles Portis

Gringos was the last of Portis’s five novels. I read the other four greedily last year, and pulled them all out when he passed away in February. I started in on Gringos, casually, then just kept reading. Sweet and cynical, spiked with strange heroism, strange grace, and very, very funny, Gringos might just be my favorite Portis novel. But I’d have to read them all again to figure that out.

Titus Alone, Mervyn Peake

A beautiful mess, an episodic, picaresque adventure that breaks all the apparent rules of the first two books. The rulebreaking is fitting though, given that Our Boy Titus (alone!) navigates the world outside of Gormenghast—a world that doesn’t seem to even understand that a Gormenghast exists (!)—Titus Alone is a scattershot epic. Shot-through with a heavy streak of Dickens, Titus Alone never slows down enough for readers to get their bearings. Or to get bored. There’s a melancholy undercurrent to the novel. Does Titus want to get back to his normal—to tradition and the meaningless lore and order that underwrote his castle existence? Or does he want to break quarantine?

The Wig, Charles Wright

Hilarious stuff. I read most of it on a houseboat in Jekyll Island, right before lockdown.

Nog, Rudolph Wurlitzer

Rudolph Wurlitzer’s 1969 cult novel Nog is druggy, abject, gross, and shot-through with surreal despair, a Beat ride across the USA. Wurlitzter’s debut novel is told in a first-person I that constantly deconstructs itself, then reconstructs itself, then wanders out into a situation that atomizes that self again.

I should’ve loved it, but I didn’t.

I reviewed it here.

Herman Melville, Elizabeth Hardwick

Typee, Herman Melville

Like a lot of people I was going out of my mind in April of 2020. Elizabeth Hardwick’s lit-crit bio of Melville isn’t necessarily great, but she does work in big fat slices of his texts, making it a kind of comfort read. It also led me to read Typee for the first time, a horny and good novel.

Fade Out, Rudolph Wurlitzer

I liked it more than Nog and wrote about it here.

Welcome Home, Lucia Berlin

A slight and unfinished collection of memoir-slices that will appeal to those already familiar with Berlin’s autofiction.

Reckless Eyeballing, Ishmael Reed

Reed’s 1986 novel skewers Reaganism, but there’s a marked shift from the surreal elastic slapstick anger of Reed’s earlier novels (like 1972’s Mumbo Jumbo). That elastick anger starts to harden into something far more bitter, harder to chew on.

Lake of Urine, Guillermo Stitch

A very weird book. I felt awful that I could never muster a proper review of it. Weird book, indie press, all that. I felt less bad when Dwight Garner praised it in The New York Times. What is Lake of Urine? That was my trouble in reviewing it. The plot is, uh, wild, to say the least. Zany, elastic, slapstick, and often surreal, Stitch’s novel is all over the place. He seems to do whatever he wants on each page with a zealous energy that’s difficult to describe. Great stuff.

Mr. Pye, Mervyn Peake

I recall enjoying it but thinking, Oh, this isn’t Gormenghast stuff.

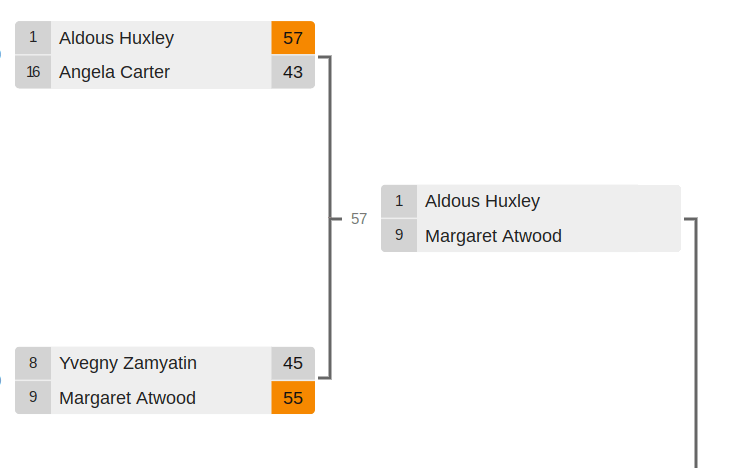

Bleeding Edge, Thomas Pynchon

I wrote about it here. What may end up being the last Pynchon novel was also the last one I read. It turned out to be much, much better than I thought it would be. It also made me very, very sad. It reminded me of our huge ideological failure after 9/11, an ideological failure we are watching somehow fail even more today.

São Bernando,Graciliano Ramos; translation by Padma Viswanathan

I enjoyed São Bernardo mostly for the narrator’s voice (which reminded me very much of Al Swearengen of Deadwood). Through somewhat nefarious means, Paulo Honorio takes over the run-down estate he used to toil on, restores it to a fruitful enterprise, screws over his neighbors, and exploits everyone around him. He decries at one point that “this rough life…gave me a rough soul,” which he uses as part confession and part excuse for his failure to evolve to the level his younger, sweeter wife would like him to. São Bernardo is often funny, but has a mordant, even tragic streak near its end. Ultimately, it’s Honorio’s voice and viewpoint that engages the reader. He paints a clear and damning portrait of himself and shows it to the reader—but also shows the reader that he cannot see himself.

The Unconsoled, Kazuo Ishiguro

Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Unconsoled is over 500 pages but somehow does not read like a massive novel, partly, I suppose, because the novel quickly teaches you how to read the novel. The key for me came about 100 pages in, when the narrator goes to a showing of 2001: A Space Odyssey starring Clint Eastwood and Yul Brynner. There’s an earlier reference to a “bleeper” that stuck out too, but it’s at the precise moment of this alternate 2001 that The Unconsoled’s just-slightly-different universe clicked for me. Following in the tradition of Kafka’s The Castle, The Unconsoled reads like a dream-fever set of looping deferrals. Our narrator, Ryder, is (apparently) a famous pianist who arrives at an unnamed town, where he is to…do…something?…to help restore the town’s artistic and aesthetic pride. (One way we know that The Unconsoled takes place in an alternate reality is that people care deeply about art, music, and literature.) However, Ryder keeps getting sidetracked, entangled in promises and misunderstanding, some dark, some comic, all just a bit frustrating. There’s a great video game someone could make out of The Unconsoled—a video game consisting of only side quests perhaps. Once the reader gives in to The Unconsoled’s looping rhythms, there’s an almost hypnotic pleasure to the book. Its themes of family disappointment, artistic struggle, and futility layer like musical motifs, ultimately suggesting that the events of the novel could take place entirely in Ryder’s consciousness, where he orchestrates all the parts himself. Under the whole thing though is a very conventional plot though—think a Kafka fanfic version of Waiting for Guffman.

The Counterfeiters, Hugh Kenner

I wanted to like it a lot more than I did.

Animalia, Jean-Baptiste Del Amo; translation by Frank Wynne

Animalia begins in rural southwest France at the end of the nineteenth century, and ends at the end of the twentieth century, chronicling the hardships of a family farm. The preceding sentence makes the novel sound possibly hokey: No, Animalia is a visceral, naturalistic, and very precise rendering of humans as animals. I had to read Animalia in stages, essentially splitting its four long chapters into novellas. Animalia made me physically ill at times. It’s an excellent novel.

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Muriel Spark

Loved it! Can’t believe I hadn’t read Spark until 2020. Went on a binge.

The Girls of Slender Means, Muriel Spark

I liked it even more than Prime. Slender Means unself-consciously employs postmodern techniques to paint a vibrant picture of what the End of the War might feel like. The climax coincides with the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the title takes on a whole new meaning, and the whole thing unexpectedly ends in a negative religious epiphany.

Loitering with Intent, Muriel Spark

My favorite of the four I read by Spark this year: funny, mean, angry postmodern perfection.

Memento Mori, Muriel Spark

A novel that about aging, memory, loss, and coming to terms with death. I was surprised to learn that this was Spark’s third novel, and that she would’ve been around 41—my age—when it was published. Most of the characters are over seventy, and Spark inhabits their consciousnesses with a level of acuity that surprised me. The weakest of the four I read, but still good.

Cherry, Nico Walker

I initially liked Walker’s war-drug-crime-romance-autoficition Cherry–the sentences are zappers and the wry, deadpan delivery approximates an imitation of Denis Johnson. Halfway through the charm starts to wear off; its native ugliness fails to compel, even Walker keeps pushing for the sublime in each chapter, only to puncture it in some way. I probably would’ve liked it at 20.

Skin Folk, Nalo Hopkinson

A mixed bag of fantasy and sci-fi stories based on Caribbean myth, some more successful than others. “A Habit of Waste” and “Slow Cold Chick” are standouts.

Zeroville, Steve Erickson

An excellent novel about film. Does in fiction what Peter Biskind’s history of New Hollywood, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls could not. Zeroville’s unexpectedly-poignant ending transcends the novel’s parodic parameters. It makes you want to go to the movies.

Citizen, Claudine Rankine

A discursive prose-poem-memoir-essay on racism, erasure, bodies, and more. I read it in two afternoons. Highly recommended.

The Divers’ Game, Jesse Ball

I kept waiting for the chapters of Ball’s “novel” to explicitly tangle together, but they never did. One of the very few cases where I feel there should be more pages in a book.

Nova, Samuel R. Delany

I couldn’t make it through Delany’s cult favorite Dhalgren a few years back, but Nova was easier sledding. The book is a riff on Moby-Dick, tarot, monoculture, and the grail quest. It’s jammed with ideas and characters, and if it never quite coheres into something transcendent, it’s a fun quick read (even if the ending, right from the postmodern metatextual playbook is too clever by half).

Zac’s Drug Binge, Dennis Cooper

I don’t know if Dennis Cooper’s gif novels are really novels or something else. I’m not sure if putting this gif novel on a list of books I read is any different than adding, say, a list of paintings by Mu Pan that I viewed over the year. The inclusion of ZDB also helps highlight the artificiality of a numbered list of books read in a year. (I know this list isn’t numbered, but it’s countable. I think it’s fifty-seven or fifty-eight.) It took me maybe 10 or 15 minutes to “read” ZBD while novels by Ishiguro, Pynchon, and Brunner are like 500 pages. The Ishiguro is actually pretty “easy” to read though, in a way that Zac’s Drug Binge is not. The Brunner is much “easier” than the many, many stories I read this year in The Complete Gary Lutz. The Lutz is 500 pages, and I read more of those pages than I did of some of the shorter works listed here like Rankine’s Citizen or Ball’s The Divers’ Game—but I didn’t “finish” the Lutz (and I don’t want to ever “finish” the Lutz), so its not on the list. Ditto Brian Dillon’s essay collection Suppose a Sentence, another collection that I’ve used to cleanse my palate between books. I could probably do a whole post on books like that (John Domini’s The Sea-God’s Herb, the Charles Portis Miscellany, The Minus Times Collected, etc. etc.)

You can read Zac’s Drug Binge here (and, uh, careful who you’re around if you click this link!).

Oreo, Fran Ross

Loved loved loved Oreo. The novel is thoroughly overlooked as a metafictional masterpiece. In my review, I wrote:

“Fran Ross’s 1974 novel Oreo is an overlooked masterpiece of postmodern literature, a delicious satire of the contemporary world that riffs on race, identity, patriarchy, and so much more. Oreo is a pollyglossic picaresque, a metatextual maze of language games, raps and skits, dinner menus and vaudeville routines. Oreo’s rush of language is exuberant, a joyful metatextual howl that made me laugh out loud. Its 212 pages galloped by, leaving me wanting more, more, more.”

A Different Drummer, William Melvin Kelley

I read it after Oreo…Oreo is neon zany polyglossic hijinks, crackling, zipping, and zapping. Kelley’s first novel, despite its rotating set of viewpoints (and conceit of an invented Southern state), was much more down to earth—modernist, not postmodernist—rendered in rusty oranges, dusty browns, muted greens. I enjoyed Kelley’s later novels dem and Dunfords Travels Everywheres more, but A Different Drummer could be his best book. I wrote about it here.

A Rage in Harlem, Chester Himes

Gonna read more Himes in 2021. Any tips? I loved loved loved it.

dem, William Melvin Kelley

From my review:

“As its subheading attests, dem is, like Drummer, a take on white people viewing black people, and over a half-century after its publication, many of the tropes Kelley employs here still ring painfully true. His “hero,” Mitchell Pierce is a lazy advertising executive, bored with his wife, a misogynist who occasionally longs to return to the “wars in Asia.” He’s also deeply, profoundly racist; structurally racist; the kind of racist who does not think of his racism as racism. At the same time, Kelley seems to extend little parcels of sympathy to Pierce, even as he reveals the dude to be a piece of shit, as if to say, What else could he end up being in this system but a piece of shit?“

Sátántangó, László Krasznahorkai; translation by George Szirtes

Years ago I put Sátántangó on a list of books I started the most times without finishing. This summer I listened to the audiobook version while I painted the interior of my house. The novel’s postmodern ending made me pick up the physical copy I acquired like eight years ago, making Sátántangó the only novel I re-read this year.

Edition 69, Jindřich Štyrský, Vítězslav Nezval, František Halas, and Bohuslav Brouk; translation by Jed Slast

Hey yo you like horny Czech interwar surrealism?

Lancelot, Walker Percy

The first Percy I read, and so far, my favorite–a postmodern Gothic screed against postmodernity. I reviewed it here.

The Moviegoer, Walker Percy

Percy’s first novel is probably much better than I credited in my review, but I was disappointed after the claustrophobic zany madness of Lancelot. I think if The Moviegoer were the first Percy I read it would have been the last.

Dunfords Travels Everywheres, William Melvin Kelley

My favorite of the three Kelley novels I read this year.

Edisto, Padgett Powell

I read most of Padgett Powell’s 1984 debut Edisto in a few sittings, settling down easily into its rich evocation of a strange childhood in the changing Southern Sea Islands. I’d always been ambivalent about Powell, struggling and failing to finish some of his later novels (Mrs. Hollingsworth’s Men; The Interrogative Mood), but Edisto captured me from its opening lines. The story takes two simple tacks–it’s a coming of age tale as well as a stranger-comes-to-town riff. Powell’s sentences are lively and invigorating; they show refinement without the wearing-down of being overworked. The book is fresh, vital.

When I finished Edisto, I thought I’d go for some more early Padgett. I picked up his second novel, A Woman Named Drown, started it that afternoon, and put it down 70 pages later the following afternoon. There wasn’t a single sentence that made me want to read the next sentence. Worse, it was turning into an ugly slog, a kind of attempt to refine Harry Crews’s dirty south into something closer to grimy eloquence. I like gross stuff, but this wasn’t my particular flavor.

The Orange Eats Creeps, Grace Krilanovich

I remember buying this book very clearly. The yellow spine called to me; the fact it was a Two Dollar Radio title; the title itself; and then, the blurb from Steve Erickson. From my review:

“Krilanovich’s novel is coated in brown-grey paste, an accumulation of scum and cum and blood, a vampiric solution zapped by orange bolts of sex, pain, drugs, and rocknroll. It’s a riot grrrl novel, a psychobilly novel, a crustgoth novel. It’s a fragmented, ugly, revolting mess and I loved it. The Orange Eats Creeps is ‘A vortex of a novel,’ as Steve Erickson puts it in his introduction, that will alternately suck in or repel readers.”

The Silence, Don DeLillo

In my unkind review, I wrote:

“The Silence is a slim disappointment, a scant morality play whose thinly-sketched characters speak at (and not to) each other liked stoned undergrads. At least it’s short.”

Motorman, David Ohle

David Ohle’s lean mean mutant Motorman is a dystopia carved from strange stuff. Ohle’s cult novel leaves plenty of room for the reader to wonder and wander around in. Abject, spare, funny, and depressing, Motorman sputters and jerks on its own nightmare logic. Its hapless hero Moldenke anti-quests through an artificial world, tumbling occasionally into strange moments of agency, but mostly lost and unillusioned in a broken universe. I loved it.

Two Stories, Osvaldo Lamborghini; translation by Jessica Sequeira

Not sure if I found a book so baffling all year.

Stand on Zanzibar, David Brunner

John Brunner’s big fat dystopian novel Stand on Zanzibar frankly overwhelmed me and then sorta underwhelmed me there at the end. This sci-fi classic is a big weird shaggy dog that managed to predict the future in all kinds of ways, and it’s mean and funny, but it’s also bloated and booming, the kind of novel that sucks all the air out of the room. It’s several dozen essays dressed up as sci-fi adventure—not a bad deal in and of itself—but there’s very little space left for the reader

Fat City, Leonard Gardner

Fat City is about an “old” boxer (he’s not thirty) on the way out of his career and a young boxer on the rise. (Rise here is a really suspect term.) I really can’t believe I was 41 when I read this. I should’ve read it at 20. I wouldn’t have understood it the same way, of course, and the biggest sincerest compliment I can pin on the novel is that I would’ve loved it at 20 but I know that I would’ve appreciated it more 20 years later. There are plenty of novels that I read and think, Hmm, would’ve loved this years ago, but now, nah, but Fat City is wonderful. It’s a boxing story, sure, but it’s really a book about bodies breaking down, aging, getting stuck in dreams and fantasies. Gardner’s only novel (!) is simultaneously mock-tragic and real tragic, pathetic and moving, and very very moving. Great stuff.

Dog Soldiers, Robert Stone

I read Robert Stone’s Dog Soldiers on the late David Berman’s recommendation) and loved it. Set at the end of the Vietnam War, Dog Soldiers is about a heroin deal going sideways. The CIA is involved, some twisted Hollywood folks, and a fallen cult leader. Everyone’s a bit grimy. I guess it comes from the Hemingway tree, or really, maybe, the Stephen Crane tree—Denis Johnson’s tree, Leonard Gardner’s tree, Raymond Carver’s tree, etc. It reminded me a lot of Johnson’s Angels (and, to some extent, Tree of Smoke), but also Russell Banks’s 1985 novel Continental Drift—and Gardner’s Fat City.

Dog Soldiers gets better and better and ends with an ecstatic punchline—a big Fuck you to God in the whirlwind. Great stuff.

Nothing but the Music, Thulani Davis

In my review, I wrote:

“Nothing but the Music cooks raw joy and raw pain into something sublime. I like poems best when they tell stories, and Davis is a storyteller. The poems here capture place and time, but most of all sound, sound, rhythm, and sound. Lovely stuff.”

Love in the Ruins, Walker Percy

Loved this one—more in line with the madness of Lancelot than the ennui of The Moviegoer, Love in the Ruins posits a USA falling apart to reveal there never was a center.

The Hearing Trumpet, Leonora Carrington

From my review:

“Leonora Carrington’s novel The Hearing Trumpet begins with its nonagenarian narrator forced into a retirement home and ends in an ecstatic post-apocalyptic utopia “peopled with cats, werewolves, bees and goats.” In between all sorts of wild stuff happens. There’s a scheming New Age cult, a failed assassination attempt, a hunger strike, bee glade rituals, a witches sabbath, an angelic birth, a quest for the Holy Grail, and more, more, more.”

The Oyster, Dejan Lukic and Nik Kosieradzki

I still need to write a proper review of this one. It’s something between an essay and a prose-poem and an aesthetic object.

Heroes and Villains, Angela Carter

One of Carter’s earlier novels, Heroes and Villains takes place in a post-apocalyptic world where caste lines divide the Professors, the Barbarians, and the mutant Out People. After her Professor stronghold is raided, Marianne is…willingly abducted?…by the barbarian Jewel. Marianne goes to live with the Barbarians, and ends up in a weird toxic relationship with Jewel, marked by rape and violence. Heroes and Villains throws a lot in its pot—what is consent? what is civilization? what is language?—but it’s a muddled, psychedelic mess in the end.

Just Us, Claudia Rankine

A short, sometimes painful read, Just Us is a mix of essaying and poetry that documents the horrors of the past few years against the backdrop of the horrors of all American history, all in a personal, moving way.

Lolly Willowes, Sylvia Townsend Warner

Starts subtle and ends sharp. A mix of satire and earnestness, purely modern, wonderful stuff. Our hero surmises at the end that Satan might actually be quite stupid. I love her.

[Ed. note–some of the language of these annotations has been recycled from previous posts.]