-

- black eyes like two deep wells

- He seemed less like a child than like a strand of seaweed.

- little particles of his own filth floated, tiny bits of skin that traveled like submarines toward an inlet the size of an eye, a calm, dark cove, although there was no calm, and all that existed was movement

- watching the fragments of his body drift away in all directions, like space probes launched at random across the universe

- a region very like hell

- he moved across the surface of the earth like a novice diver along the seafloor

- strands that really did look like fingers

- The Poles look like chickens, but pluck four feathers and you’ll see they’ve got the skin of swine.

- They look like starving dogs but they’re really starving swine, swine that’ll eat anyone, without a second thought, without the slightest remorse.

- They’re like swine disguised as Chihuahuas.

- A churning gray like pus.

- like ghost towns

- like blood and rotting meat

- moving like a diver

- like a night diver

- What was it about the boy that made him look like seaweed?

- that dark sea, a sea like a pack of wolves

- dark waves like forest beasts

- the body of young Reiter floating like uprooted seaweed, upward, a brilliant white in the underwater space

- sometimes the baby looked like a bag of rubbish left on a pebbly beach

- other times like Petrobius maritimus, a marine insect that lives in crevices and rocks and feeds on scraps, or Lipura maritima, another insect, very small and dark slate or gray, its habitat the puddles among rocks

- like prophecies

- “My son,” said the one-legged man.

“He looks like a giraffe fish,” said the former pilot, and he laughed. - that weekend was like a month

- samurais were like fish in a waterfall but the best samurai in history was a woman

- an eternity, like the minutes of those condemned to die

- like the minutes of women who’ve just given birth and are condemned to die

- like luxurious excrescences or heartbeats

- go forth like the keeper of a swarm of bees, except that this beekeeper wasn’t protected by a mesh suit or a helmet and woe betide the bee that tried to sting him, even if only in thought.

- like the eyes of a hawk that flies and delights in its flight, but that also maintains a

watchful gaze - noise like crumpled pages, noise like burned books

- cavorted like a mermaid

- he watched the sunrise as it washed like a wave over the city, drowning them all

- darts along like a squirrel

- the village, like a black lump set or encrusted in the darkness

- like a box from some scientific research center where glove-wearing German scientists pack away something with the power to destroy the world and Germany too

- like seeing a giraffe go off in a pack of wolves, coyotes, and hyenas

- the seaweed jungle was like the locks of a dead giant

- like sheep or little goats

- He saw hills or rocky outcroppings that looked like ships about to sink, prows lifted, like enraged horses, nearly vertical

- the towers of the castle like two gray candles on a deserted altar

- being here is like being buried alive

- like a shadow

- more like a horse than a man

- like an engraving of a worker or artisan, an innocent passerby suddenly blinded by a ray of moonlight

- swaying back and forth, like a little shepherdess gone wild in the vastness of Asia

- reality was increasingly vague, more like a dream

- d her eyes, a washed-out blue, like the eyes of a blind woman

- strolling like philosophers

- woods like dark islands in the middle of endless wheat fields

- a black fog rose before his eyes, full of granulated dots like a rain of meteors

- he fired and walked, like someone strolling and taking photographs, until the

fort exploded - looking as if they were starving or like pupils at a reform school

- the sergeant looked like an ant that gradually grew bigger and bigger

- already approaching old age, like the biblical Abraham and Sarah

- drank like a condemned woman

- more like a strand of seaweed than a human being

- the seaweedlike extraterrestrial

- like a burning doll

- a rending violence, like a claw, but not a claw that did any damage

- like a claw that pounces and floats in the middle of the room, like a helium balloon, a selfconscious claw, a claw-beast that wonders what in God’s name it’s doing in this rather untidy room, who that old man is sitting at the table, who that young man is standing with tousled hair, then falls to the floor, deflated, returned once more to nothing.

- like something rotting

- like an orphan, a self-designated orphan

- On the subject of art, a politician with power is like a colossal pheasant, able to crush mountains with little hops, whereas a politician without power is only like a village priest, an ordinary-sized pheasant.

- They lived like garbagemen. They were the garbagemen of the jungle

- like birds

- like a horror painting

- other poets shun them like lepers

- the sudden appearance of this incredible woman is like a miracle

- inspecting the dead like someone who inspects a lot for sale or a farm or a country house

- like madmen escaped from an asylum

- From a hill he saw a column of German tanks moving east. They looked like the coffins of an extraterrestrial civilization.

- feeling something very strange that sometimes seemed like happiness and other times like a guilt as vast as the sky

- the bottom of the river was like a gravel road

- a vague noise, like the clatter of furniture, as if sick people were moving furniture around

- the full moon filtered through the fabric of the tent like boiling coffee through a sock

- my name has grown like a malignant tumor and now it turns up on the most unlikely documents

- the light sweeping the tent like a bird’s wing or a claw

- dreamlike

- they seemed less like children than like the skeletons of children, abandoned sketches, pure will and bone

- like girls who’ve just woken from a terrible nightmare

- like the habitues of racetracks who commit suicide in cheap rented rooms or hotels tucked away on back-streets frequented by gangsters

- like a murderer

- like a ragpicker’s room

- he drank like a Cossack

- the killer will open the window of my room and come tiptoeing in like a nurse

and slit my throat, bleed me dry - I would never manage to create anything like a masterpiece.

- He writes like someone taking dictation.

- his old man’s neck, like the neck of a turkey or a plucked rooster

- his gray temples like a stormy sea

- deep eyes that at the slightest tilt of his head seemed at times like two endless tunnels, two abandoned tunnels on the verge of collapse.

- a kind of crepuscular lethargy crept from under the doors like poison gas

- Mickey, like the mouse

- Everything is burning. It looks more like the moon than Normandy.

- like the living dead, zombies, cemetery dwellers, soldiers without eyes or mouths, but with penises

- like the soldier who was trapped under a pile of corpses and there, beneath the corpses and the snow, he dug a little cave with his regulation shovel, and

to pass the time he jerked off, more boldly each time, because once the fear and surprise of the first few instants had vanished, all that was left was the fear of death and boredom, and to stave off boredom he began to masturbate, first timidly, as if he were seducing a peasant girl or a little shepherdess, then with increasing determination, until he managed to bring himself off to his full satisfaction, and he went on like that for fifteen days, in his little cave of corpses and snow, rationing his food and indulging his urges, which didn’t make him weaker but rather seemed to retronourish him, as if he had drunk his own semen or as if after going mad he had found a forgotten way back to a new sanity, until the German troops counterattacked and discovered him - not dirty or like shit or urine, nor like rot or worm meat

- like Ali Baba’s cave

- like a doll’s house, a cabin, a hut, a place that existed on the edge of time and remained fixed in a willed and imaginary childhood, comfortable and unspoiled.

- like something out of a fairy tale

- Then he began to talk, still pacing, about Europe, Greek mythology, and something

vaguely like a police investigation - like something out of a PreRaphaelite painting

- a little white-chocolate house with beams like slabs of dark chocolate, surrounded by a little garden in which the flowers looked like paper cutouts and a lawn trimmed with mathematical precision

- all human beings are obliged to bear until their deaths, like the rock of Sisyphus

- throbbed like the ripped-out heart of an Aztec victim

- typewriter was like a heart, a giant heart beating in the middle of the fog and chaos

- the stain of blood was like a giant rose in full bloom

- and the mountains multiplying in the night, all white, like nuns with no worldly ambitions.

- a laugh that sounded to Archimboldi like a cascade of ice

- she didn’t weigh a thing anymore, it was like climbing up with a bundle of sticks

- like a couple of vagabonds

- buildings propping each other up like little old Alzheimer’s patients, a jumble of houses and mazelike passageways where distant voices could be heard, worried voices asking questions and offering answers with great dignity

- Like the final surroundings of Sisyphus

- like a phantom

- He smiled like a father

- the place looked like a graveyard

- the old man in pajamas looked less like a vanished novelist than like a justly forgotten novelist, the typical hard-luck bad French novelist, most likely born at the wrong time

- a sweet and chirping voice, like the water of a brook that runs over a bed of flat stones

- The essayist looked like a cigarette covered with a handkerchief.

- arm in arm like two ex-lovers who no longer have many secrets to tell

- a car like a hearse awaited her

- the days were like nights and the nights like days

- sometimes the days and nights were unlike anything, everything was a continuum of blinding brightness and explosions

- Mouths like carrots, with peeling lips, and noses like wet potatoes

- like women who haven’t yet begun to menstruate

- he preferred someone decent and hardworking, who wouldn’t suck his blood like a

vampire - Her suffering was like the screech of chalk on a blackboard. As if a boy were dragging a piece of chalk across a blackboard on purpose to make it screech.

- like looking for a needle in a haystack

- slept like a baby

- The sounds she heard were like the sounds of the abyss.

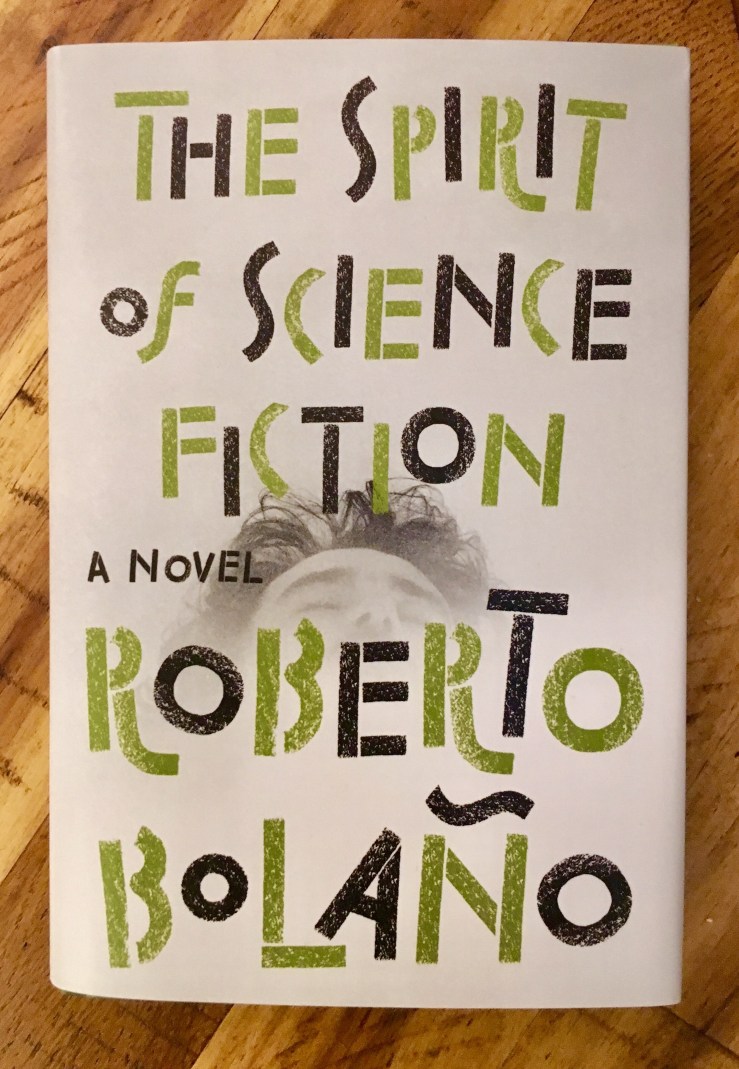

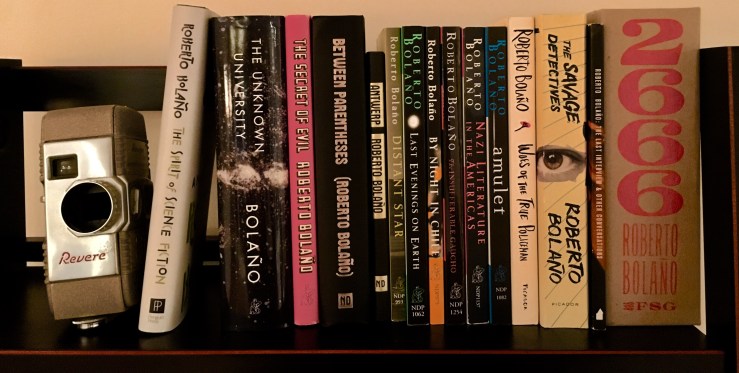

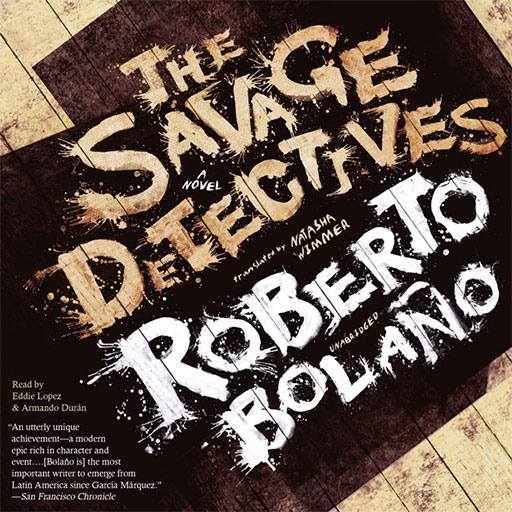

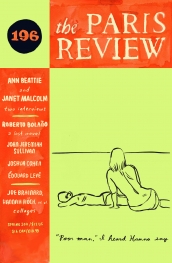

These similes are from “The Part About Archimboldi,” the fifth part of 2666, a novel by Roberto Bolaño, in English translation by Natasha Wimmer.

Two years ago, a typed manuscript for Roberto Bolaño’s unpublished novel The Third Reich The Third Reich was discovered. The Paris Review is serializing the novel, publishing it in full over four issues in a translation by Natasha Wimmer. I finished the first part of The Third Reich last night, reading the 63 pages in one engrossing session.

Two years ago, a typed manuscript for Roberto Bolaño’s unpublished novel The Third Reich The Third Reich was discovered. The Paris Review is serializing the novel, publishing it in full over four issues in a translation by Natasha Wimmer. I finished the first part of The Third Reich last night, reading the 63 pages in one engrossing session.