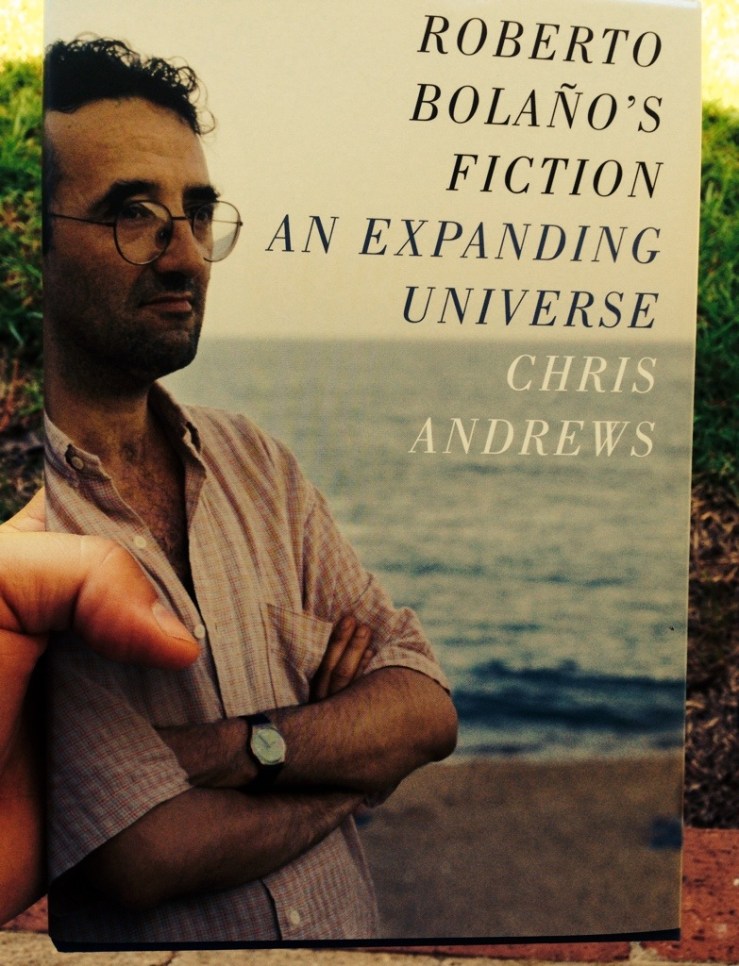

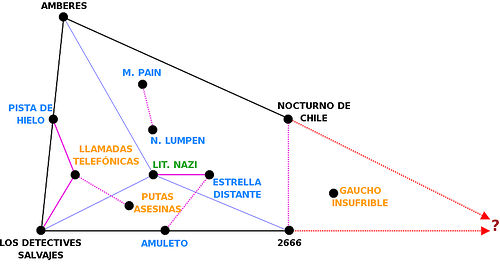

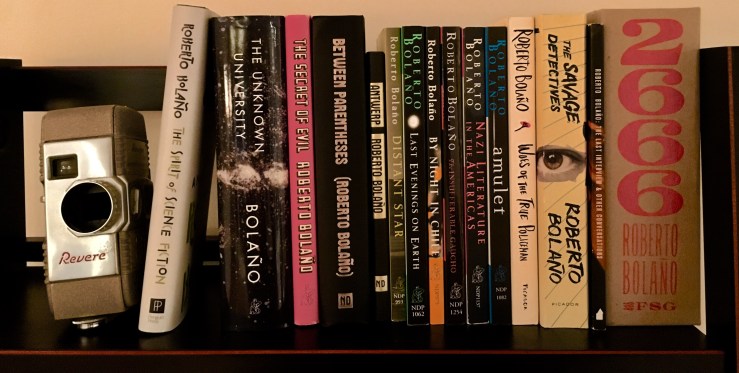

Roberto Bolaño died at the young age of 50 in 2003, just as his work was beginning to gain a wider audience and broader critical acclaim. It wasn’t until after his death that his work was published in English. Just a few months after Bolaño died, New Directions published By Night in Chile in translation by Chris Andrews. A year later, they published Andrews’ translation of Distant Star, and completed the loose trilogy of these short novels with the publication of Amulet in early 2007. A few months after the publication of Amulet, FS&G published Natasha Wimmer’s translation of The Savage Detectives, which had been originally published in Spain a decade earlier. By the time Wimmer’s translation of 2666 hit the shelves in 2008, Bolaño had become a literary sensation in the U.S., only half a decade after his death.

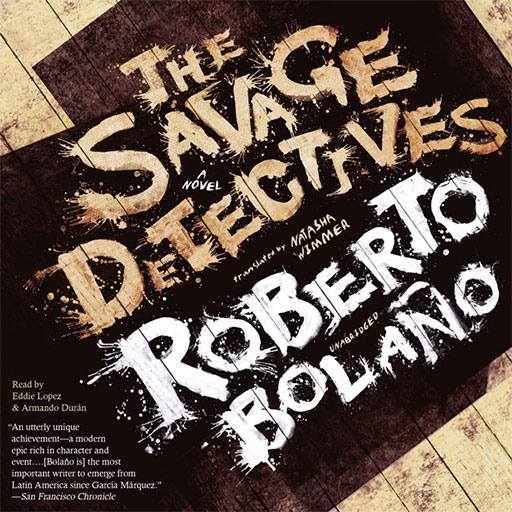

2666 is arguably Bolaño’s masterpiece, and certainly one of the defining books of the first decade of the 21st century. I read the book in a fevered rush, and then read it again, and then again. As far as I can tell, there are more essays and reviews about 2666 on Biblioklept than any other book. It was the second book I read by Bolaño—admittedly, a first reading of The Savage Detectives left me a perplexed and cold, but I’ve since returned to that novel with a broader understanding and appreciation of Bolaño’s project, a project that seemed to expand yearly after Bolaño’s demise.

Indeed, it became something of a joke in literary circles, What, another Bolaño? He drops books from beyond the grave like Tupac drops albums! There are the short story collections (translated by Andrews) that trickled out between 2007 and 2012, along with harder to classify collections, like The Secret of Evil (Andrews, 2012) and Nazi Literature in the Americas (Andrews, 2008), a jangling set of keys to the Bolañoverse. Another set of keys came in the wonderful collection The Unknown University, a compendium of Bolaño’s poetry in translation by Laura Healy published by New Directions in 2013.

Then there are the novels that seemed to arrive every year or so: The Skating Rink (Andrews, 2009), Monsieur Pain (Andrews, 2010), Antwerp (Wimmer, 2010), The Third Reich (Wimmer, 2011), A Little Lumpen Novelita (Wimmer, 2014). Bolaño composed these pieces primarily in the 1980s, when he still thought of himself as a poet. These novels lack the vitality and vibrancy of his later work—the short story collections, the trilogy of short novels that began with Distant Star, and his big books, The Savage Detectives and 2666.

Indeed, for many Bolaño fans, reading these early novels feels like its own project—winnowing for seeds, pulling at the threads that will cohere into something grander in the Bolaño’s future (which, from a readerly perspective, is the past). So when FS&G published Wimmer’s translation of Woes of the True Policeman in 2012, it was hard for many readers to see the novel as anything but ancillary materials for 2666—it was hard to read the novel as a discrete work, on its own. Instead, the question Woes asked Bolaño fans was, Where does this fit in the Bolañoverse?

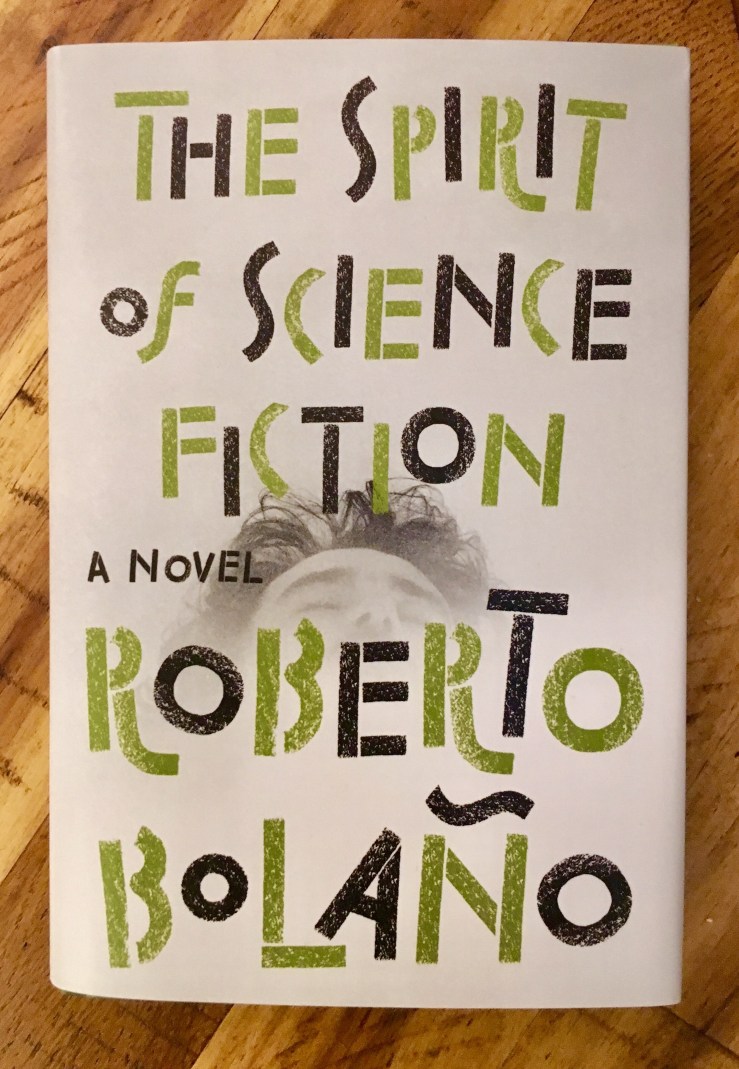

The same question is in play for the latest posthumous Bolaño release, The Spirit of Science Fiction (Penguin, Wimmer). A simple read, and one that is not incorrect, is that The Spirit of Science Fiction feels like a trial run at The Savage Detectives. In particular, Spirit blueprints the first and third sections of The Savage Detectives, sections that revolve around the immature adventures of two would-be poets in Mexico City in the 1970s. Instead of Arturo Belano and Ulisses Lima though, we get Jan Schrella (“alias Roberto Bolaño”) and Remo. These two heroes divide Bolaño’s literary ambitions into poetry and prose, posterity and potboiler pulp fiction. In The Savage Detectives, Arturo Belano and Ulisses Lima will synthesize these ambitions more grandly in their literary quest.

Jan and Remo’s questing in Spirit isn’t quite as grand. Remo wants to figure out why there are so many literary magazines in Mexico City; Jan spends his days writing to American science fiction writers. They manage to get mixed up with a set of sisters and their friend—poets of course. (Everyone in the novel is a poet, even—especially—a skinny motorcycle mechanic). The sisters prefigure the Font sisters of The Savage Detectives, and much of their plot feels like a sketch for that richer work.

Their friend Laura is a more interesting figure—a bit sinister, a cipher really, an iteration of the Lisas and Lupes that we find elsewhere in Bolaño’s fiction—in particular in some of the poetry collected in The Unknown Univeristy. Indeed, the final section of The Spirit of Science Fiction, “Mexican Manifesto,” was originally published in a different form in that collection. Some of the best parts of Spirit feel like failed poems, poems that want to be prose, unpoetical, mad, howling, jolly poems. Like 2666 or The Savage Detectives, the plot of Spirit careens, splinters, dares the reader to put the fragments together.

There is structure though: The main of the novel is told in first-person perspective by Remo. He’s seventeen, and has come from Chile to Mexico City with his friend Jan to live destitute in a garret and write bad articles under a pseudonym while he pursues his poetry. He gets sidetrack by love and other matters.

Running counter to this narrative are the letters that Jan writes to American sci-fi authors like Ursula K. Le Guin and Alice Sheldon. In a metatextual nod, Jan (“alias Roberto Bolaño”) also writes to Sheldon’s alias James Tiptree, Jr. Jan’s letters are a highlight of the novel, setting youthful arrogance and romantic idealism against a kind of quasi-tragic pathos. In a letter to Philip José Farmer, Jan (alias Roberto) suggests that a literary sci-fi anthology called American Orgasms in Space be published as a means to end war and cultivate brotherhood between Latin Americans and North Americans. The punchline to the letter is hilarious. Before signing off (“Warmly”), Jan informs the author of the Riverworld series that, “A week ago, I lost my virginity.”

A third strand runs throughout Spirit. In a series of segments set in some presumable future, a female journalist interviews Jan in the middle of a bizarre drunken party somewhere in the dark woods. Jan has won a prize for a sci-fi novel that he summarizes for the journalist who listens, downing vodka after vodka. Jan’s prize-winning sci-fi novel meshes elements that will be familiar to Bolaño’s readers—apocalyptic desolation, failed communication, esoteric histories of Latin America, mystery authors. Etc. It’s even partially set in the Unknown University. The interview segments seem perched on the edge of their own sinister apocalypse, a typically-Bolañoesque move, as if a seemingly-normal situation might topple over into malevolence at any moment. Unfortunately though, these sections seem to have been abandoned.

Indeed, much of Spirit reads like a patchwork of abandoned drafts, riddled with material and ideas that will pop up in later novels—the tabletop gaming of The Third Reich, the fascination of Nazi iconography we see in Nazi Literature in the Americas, the reckoning of post-colonialism which belongs to The Savage Detectives in particular, as well as the Bolañoverse as a whole. Too, Spirit shares the ominous swells and sinister reverberations that we identify with both Bolaño’s prose and poetry—the book shows the joyful optimism of youth poised on the cusp of unnameable disaster.

And there are plenty of great sections in The Spirit of Science Fiction: Jan desribing the entirety of a Gene Wolfe space novella to his friend, but mashing it into a vision of the screenwriter Thea von Harbou and her Nazi sympathies; the story of a Belgian-occupied village in the Congo that falls into a madness of woodworking, a madness that leads to general slaughter; a nervous late-night ride on a stolen motorcycle named the Aztec Princess; “the story of how Georges Perec, as a boy, prevented a duel to the death between Isidore Isou and Altagor in an old neighborhood in Paris”; a grotesque and enthralling final sequence in a semi-legal Mexico City bathhouse that channels the dark ghost of William S. Burroughs.

In short, there’s a lot of great writing in The Spirit of Science Fiction—plenty of moments that satisfy, if only temporarily, our cravings for more Bolaño. And yet the novel is clearly unfinished, which, if you’ve read Bolaño—and I’m assuming if you’ve hung out this far into this review, you’ve read Bolaño, and like, if you haven’t read Bolaño, I think he’s great, and a great starting point for reading him would be Distant Star or the short story collection Last Evenings on Earth—and, where was I? Okay: The Spirit of Science Fiction is clearly an unfinished piece, which, if you’ve read Bolaño, may seem like a Bolañoesque feature—his works point to an indeterminancy, an oblique, inconclusive, resolutely unfinishedness. (Think of the final lines/images of The Savage Detectives, for example).

And yet Spirit’s unfinishedness is not of a piece with the general aporia that belongs to Bolaño’s finished unfinished works—it seems, rather, an abandoned project, a draft to be repurposed later. Which, of course, it was—we already got the material that Spirit helped inspirit—in The Savage Detectives, in Nazi Literature, in 2666—in Bolaño’s best materials.

Paradoxically then, The Spirit of Science Fiction leaves the reader—by which I mean the Bolaño fan—by which I mean, let’s be honest, this Bolaño fan—Spirit leaves this reader hungry for more, for the pages to gallop on and on, to careen into more dread and manic joy and bad poetry and good poetry and pilfered stories and excessive metaphors. More: More Bolaño.

And then how could this review be a complaint? Well it isn’t. I enjoyed The Spirit of Science Fiction, was hungry for it before I even touched it, and then left hungry, wanting more: More Bolaño.