New from Twisted Spoon Press, Edition 69 collects three previously-untranslated volumes of Czech artist and writer Jindřich Štyrský’s private-press books of the same name. Beginning in 1931, Štyrský published six volumes of Edition 69. The series was devoted to outré erotic writing and art — “pornophilia,” as the biologist/poet/philosopher Bohuslav Brouk puts it in an essay accompanying the sixth and final volume of Edition 69.

Because of Czech censorship laws, Štyrský’s project was limited to subscribers and friends, with each volume running under 200 editions (the final volume was limited to 69 copies). Undoubtedly, the material in Edition 69 would present an affront—indeed an intentional affront—to the “supercilious psyches of the ruling peacocks,” to again borrow from Brouk (rendered wonderfully here in Jed Slast’s estimable English translation—I should’ve mentioned Slast earlier!). Much of the material in Twisted Spoon’s new collection of Edition 69 still provokes and disturbs nearly a century after their original publication.

Three of the original volumes of Edition 69 presented Czech translations–in some cases the first—of writers like the Marquis de Sade, along with accompanying illustrations by Toyen and Rudolf Krajc. Following its mission of bringing Czech literature to an English-reading audience, Twisted Spoon’s Edition 69 collects the three volumes by Czech artists in translation by Jed Slast: Vítězslav Nezval’s Sexual Nocturne (1931), František Halas’s Thyrsos (1932), and Štyrský’s own Emilie Comes to Me in a Dream (1933). (Štyrský designed and illustrated each of these volumes.)

Nezval’s fragmentary surrealist dream-memoir Sexual Nocturne is the strongest of the three pieces in Edition 69. Nezval gives us an abject, dissolving reminiscence of an unnamed narrator’s boarding school days, centering on a trip to the local bordello and culminating in a return visit years later, one soaked in alcohol and despair. It’s a creepy and decidedly unsexy story, directly referencing Poe’s “The Raven” and Whitman’s “The City Dead-House” (and cribbing more Gothic gloom from a handful of penny dreadfuls).

Sexual Nocturne is a Freudian ramble into adolescent sexual frustration, voyeurism, and ultimately loss, loneliness, and insanity. It’s also a wonderful exploration of the connection between taboo bodily functions and taboo words. In one notable scene, our narrator sends a missive to a crush containing an obscenity, only to be discovered by the bourgeois landlord of his boarding house:

His views reflected those of society. How ridiculous. A writer is expected to make a fool of himself by employing periphrastic expressions while the word ‘fuck’ is nonpareil for conveying sexual intercourse. Fortunately there are old dictionaries where this world has its monument. How I sought it out! When the kiss of lovers pronounces it during coitus it is infused with a sudden vertigo. I have little tolerance for its disgraceful and comic synonyms. They convey nothing, just mealy-mouthed puffballs that make me want to retch when I encounter them.

The word FUCK is diamond-hard, translucent, a classic. As if adopting the appearance of a gem from a noble Alexandrine, it has, since it is forbidden, a magical power. It is one of the Kabbalistic abbreviations for the erotic aura, and I love it.

I love it! I love that second paragraph so much. It’s one of the best paragraphs I’ve read all year.

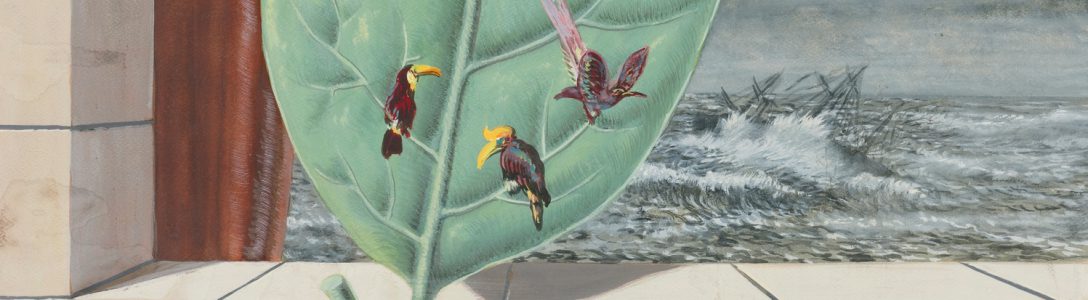

The collages by Štyrský that accompany Sexual Nocturne are reminiscent of Max Ernst’s work in A Week of Sundays, but less frenetic. At times they sync with the tale’s dream logic, and when they don’t, fine. It’s interwar surrealism, baby!

František Halas’s Thyrsos is far less successful. Halas’s poems can’t quite live up to their namesake, let alone the Sophocles’ quote that precedes them (“Not to be born is, beyond all estimation, best; but when a man has seen the light of day, this is next best by far, that with utmost speed he should go back from where he came”).

The opener, “Leda’s Sorrow,” isn’t particularly bad, but it’s nothing special either:

Other poems celebrate incest, arcadian bacchanalia, and old-man boners. Halas’s poem about cunnilingus (“The Taste of Love”) is particularly bad. Outlier “In the Field” connects the collection’s larger themes of sex-as-death’s-twin, evoking a scene of what might be a battle field, with trenches and barbed wire, a solitary man jerking off “like a demon” over what I take to be a foxhole. For the most part though, Thyrsos is a strange mix of ribald and whimsical with occasional sex tips thrown in. It’s weak stuff. In his translator’s note, Slast admits that “perhaps it’s understandable that Halas considered this thin collection of poems juvenile and much inferior to his other work.” Štyrský’s pen-and-ink illustrations are simple and charming though, even if their simple charm seems to point to the fact that Halas’s ditties are out of place in the queasy surrealism of the rest of the collection.

Štyrský’s Emilie Comes to Me in a Dream reads like a mix of dream writing and automatic writing. It’s stranger and more poetic than the prose in Nezval’s Nocturne, but neither as funny nor as profound. And yet it has its moments, as it shifts from sensuality to pornography to death obsession. “I came to love the fragrance of her crotch,” our narrator declares, and then appends his description: “a mix of laundry room and mouse hole, a pincushion forgotten in a bed of lilies of the valley.” He tells us he “was prone to seeing in dissolve,” and the prose bears it out later, in a linguistic episode that mirrors Štyrský’s surrealist collage techniques:

Later I placed an aquarium in the window. In it I cultivated a golden-haired vulva and a magnificent penis specimen and delicate veins on its temples. Yet in time I threw in everything I had ever loved: shards of broken teacups, hairpins, Barbora’s slipper, light bulbs, shadows, cigarette butts, sardine tins, my entire correspondence, and used condoms. Many strange creatures were born in this world. I considered myself a creator, and with justification.

After the dream writing, Štyrský delivers a sexually-explicit photomontage that’s simultaneously frank and ambiguous, ironic and sincere, sensual and abject. The photographic collages wed sex and death, desire and repulsion.

Štyrský’s Emilie includes a (previously-mentioned) postscript by Bohuslav Brouk, which, while at times academic and philosophical, plainly spells out that the mission of the so-called “pornophiles” is to give a big FUCK YOU to the repressed and repressive bourgeoisie. Brouk intellectualizes pornophilia, arguing against the conservative mindset that strives for immortal purity. He argues in favor of embracing corporeal animality: “The body will continue to demonstrate mortality as the fate of all humans, and for this reason any reference to human animality so gravely offends those who dream of its antithesis.” Hence, sex and death—blood, sweat, tears, semen—are the abject markers of the fucking circle of life, right? Our dude continues:

The body is the last argument of those who have been unjustly marginalized and ignored, because it demonstrates beyond question the groundlessness of all social distinctions in comparison to the might of nature.

I’ll give Brouk the last quote here because I think what he wrote resonates still in These Stupid Times.

Edition 69 has its highs and its lows, but I think it’s another important document of Czech surrealism from Twisted Spoon, and in its finest moments it reminds us that we are bodies pulling a psyche around, no matter how much we fool ourselves. Nice.