Slavoj Žižek describes Violence as “six sideways glances” examining how our preoccupation with subjective violence (that is, the personal, material violence that we can see so easily in crime, racism, etc.) masks and occludes our understanding of the systemic and symbolic violence that underwrites our political, economic, and cultural hierarchies. Žižek believes that a dispassionate “step back enables us to identify a violence that sustains our very efforts to fight violence and promote tolerance,” and that a rampant “pseudo-urgency” to act instead of think currently (detrimentally) infects liberal humanitarian efforts to help others. This is where the fun comes in. Žižek delights here in pointing out all the ways in which we fool ourselves, all the ways in which we believe we’ve gained some kind of moral edge through our beliefs and actions.

I use the words “fun” and “delight” above for a reason: Violence is fun and a delight to read. Žižek employs a rapid, discursive method, pulling examples from contemporary politics, psychoanalysis, films, poetry, history, jokes, famous apocryphal anecdotes, and just about every other source you can think of to illustrate his points. And while it would be disingenuous to suggest that it doesn’t help to have some working knowledge of the philosophical tradition and counter-traditions to best appreciate Violence, Žižek writes for a larger audience than the academy. Yet, even when he’s quoting Elton John on religion or performing a Nietzschean reading of Children of Men, Žižek’s dalliances with pop culture always occur within the gravest of backdrops. Within each of Violence‘s six chapters, there’s a profound concern for not only the Big Questions but also the big events: Žižek frequently returns to the Iraq War, the 9/11 attacks, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as major points of consideration. This concern for contemporary events, and the materiality of contemporary events, is particularly refreshing in a work of contemporary philosophy. Undoubtedly some will pigeonhole Žižek in the deconstructionist-psychoanalytical-post-modernist camp (as if it were an insult, of course)–he clearly has a Marxist streak and a penchant for Lacanian terminology. Yet, unlike many of the writers of this philosophical counter-tradition, Žižek writes in a very clear, lucid manner. There’s also a great sense of humor here, as well as any number of beautiful articulations, like this description of the “dignity and courage” of atheism:

[A]theists strive to formulate the message of joy which comes not from escaping reality, but from accepting it and creatively finding one’s place in it. What makes this materialist tradition unique is the way it combines the humble awareness that we are not masters of the universe, but just a part of a much larger whole exposed to contingent twists of fate, with a readiness to accept the heavy burden of responsibility for what we make out of our lives. With the threat of unpredictable catastrophe looming from all sides, isn’t this an attitude needed more than ever in our own times?

I’m inclined to answer, “Yes.” Highly recommended.

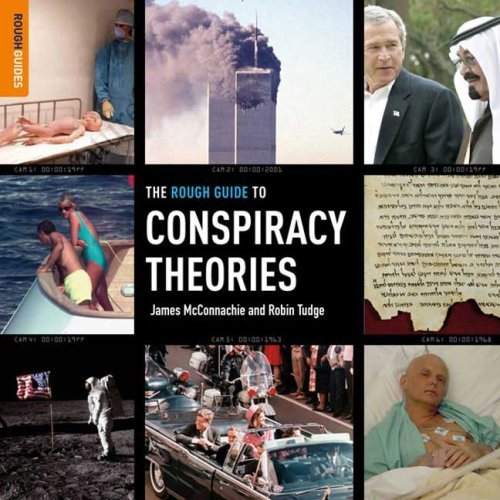

Violence, part of the new BIG IDEAS // small books series from Picador Books, is available August 1st.