One day, strolling in the Piazzetta, Hunter motioned her under the arcade and into the Library, and pointed up at Tintoretto’s Abduction of the Body of St. Mark. She gazed for some time. “Well, if that ain’t the spookiest damned thing,” she whispered at last. “What’s going on?” she gestured nervously into those old Alexandrian shadows, where ghostly witnesses, up far too late, forever fled indoors before an unholy offense.

“It’s as if these Venetian painters saw things we can’t see anymore,” Hunter said. “A world of presences. Phantoms. History kept sweeping through, Napoleon, the Austrians, a hundred forms of bourgeois literalism, leading to its ultimate embodiment, the tourist—how beleaguered they must have felt. But stay in this town awhile, keep your senses open, reject nothing, and now and then you’ll see them.”

A few days later, at the Accademia, as if continuing the thought, he said, “The body, it’s another way to get past the body.”

“To the spirit behind it—” “But not to deny the body—to reimagine it. Even”—nodding over at the Titian on the far wall—“if it’s ‘really’ just different kinds of greased mud smeared on cloth—to reimagine it as light.”

“More perfect.”

“Not necessarily. Sometimes more terrible—mortal, in pain, misshapen, even taken apart, broken down into geometrical surfaces, but each time somehow, when the process is working, gone beyond. . . .”

Beyond her, she guessed. She was trying to keep up, but Hunter didn’t make it easy. One day he told her a story she had actually already heard, as a sort of bedtime story, from Merle, who regarded this as a parable, maybe the first on record, about alchemy. It was from the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, one of many pieces of Scripture that early church politics had kept from being included in the New Testament.

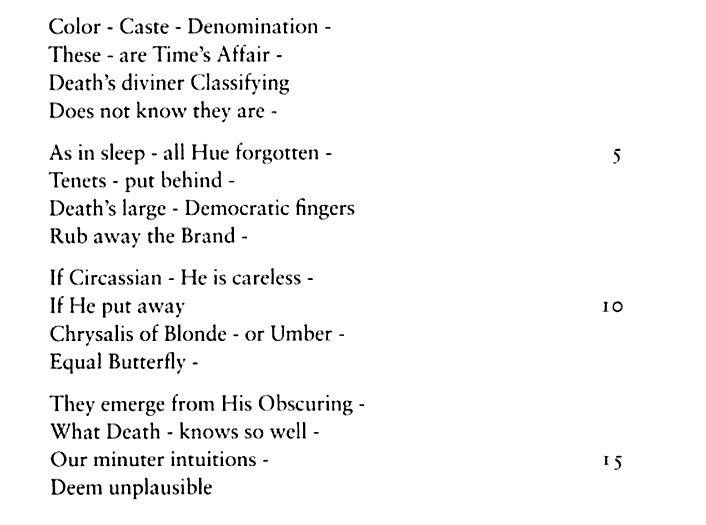

“Jesus was sort of a hellraiser as a kid,” as Merle had told it, “the kind of wayward youth I’m always finding you keepin company with, in fact, not that I’m objecting,” as she had sat up in bed and looked for something to assault him with, “used to go around town pulling these adolescent pranks, making little critters out of clay, bringing them to life, birds that could fly, rabbits that talked, and like that, driving his parents crazy, not to mention most of the local adults, who were always coming by to complain—‘You better tell ’at Jesus to watch it.’ One day he’s out with some friends looking for trouble to get into, and they happen to go by the dyer’s shop, where there’s all these pots with different colors of dye and piles of clothes next to them, all sorted and each pile ready to be dyed a different color, Jesus says, ‘Watch this,’ and grabs up all the clothes in one big bundle, the dyer’s yelling, ‘Hey Jesus, what’d I tell you last time?’ drops what he’s doing and goes chasing after the kid, but Jesus is too fast for him, and before anybody can stop him he runs over to the biggest pot, the one with red dye in it, and dumps all the clothes in, and runs away laughing. The dyer is screaming bloody murder, tearing his beard, thrashing around on the ground, he sees his whole livelihood destroyed, even Jesus’s lowlife friends think this time he’s gone a little too far, but here comes Jesus with his hand up in the air just like in the paintings, calm as anything—‘Settle down, everybody,’ and he starts pulling the clothes out of that pot again, and what do you know, each one comes out just the color it’s supposed to be, not only that but the exact shade of that color, too, no more housewives hollerin ‘hey I wanted lime green not Kelly green, you colorblind or something,’ no this time each item is the perfect color it was meant to be.”

“Not a heck of a lot different,” it had always seemed to Dally, “in fact, from that Pentecost story in Acts of the Apostles, which did get in the Bible, not colors this time but languages, Apostles are meeting in a house in Jerusalem, you’ll recall, Holy Ghost comes down like a mighty wind, tongues of fire and all, the fellas come out and start talking to the crowd outside, who’ve all been jabbering away in different tongues, there’s Romans and Jews, Egyptians and Arabians, Mesopotamians and Cappadocians and folks from east Texas, all expecting to hear just the same old Galilean dialect—but instead this time each one is amazed to hear those Apostles speaking to him in his own language.”

Hunter saw her point. “Yes, well it’s redemption, isn’t it, you expect chaos, you get order instead. Unmet expectations. Miracles.”