Watch the full version of Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu (with English subtitles).

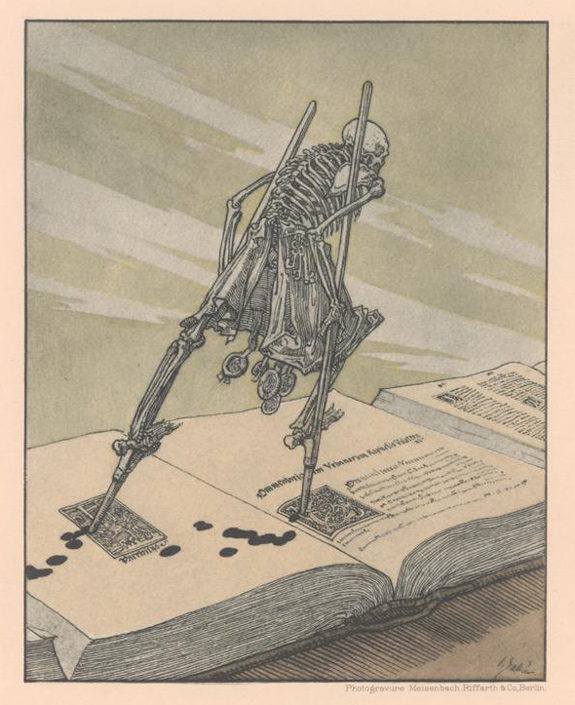

A page from Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s outstanding graphic novel From Hell, an encyclopedic account of the Jack the Ripper murders. In this scene, our evil protagonist Dr. Gull undergoes a transcendent experience, and appears to William Blake, inspiring The Ghost of a Flea.

I pulled the image of From Hell from this fantastic detailed review by Miguel at St. Orberose (far better than my own my own meager tackle at writing about the book). Plenty more images there, along with a comprehensive analysis of (what I take to be) Moore’s best work.

“The Werewolf” by Eugene Field

In the reign of Egbert the Saxon there dwelt in Britain a maiden named Yseult, who was beloved of all, both for her goodness and for her beauty. But, though many a youth came wooing her, she loved Harold only, and to him she plighted her troth.

Among the other youth of whom Yseult was beloved was Alfred, and he was sore angered that Yseult showed favor to Harold, so that one day Alfred said to Harold: “Is it right that old Siegfried should come from his grave and have Yseult to wife?” Then added he, “Prithee, good sir, why do you turn so white when I speak your grandsire’s name?”

Then Harold asked, “What know you of Siegfried that you taunt me? What memory of him should vex me now?”

“We know and we know,” retorted Alfred. “There are some tales told us by our grandmas we have not forgot.”

So ever after that Alfred’s words and Alfred’s bitter smile haunted Harold by day and night.

Harold’s grandsire, Siegfried the Teuton, had been a man of cruel violence. The legend said that a curse rested upon him, and that at certain times he was possessed of an evil spirit that wreaked its fury on mankind. But Siegfried had been dead full many years, and there was naught to mind the world of him save the legend and a cunning-wrought spear which he had from Brunehilde, the witch. This spear was such a weapon that it never lost its brightness, nor had its point been blunted. It hung in Harold’s chamber, and it was the marvel among weapons of that time. Continue reading ““The Werewolf” — Eugene Field”

From Mary F. Blain’s Games for Hallowe’en (1912):

BLIND NUT SEEKERS

Let several guests be blindfolded. Then hide nuts or apples in various parts of room or house. One finding most nuts or apples wins prize.

DUMB CAKE

Each one places handful of wheat flour on sheet of white paper and sprinkles it over with a pinch of salt. Some one makes it into dough, being careful not to use spring water. Each rolls up a piece of dough, spreads it out thin and flat, and marks initials on it with a new pin. The cakes are placed before fire, and all take seats as far from it as possible. This is done before eleven p.m., and between that time and midnight each one must turn cake once. When clock strikes twelve future wife or husband of one who is to be married first will enter and lay hand on cake marked with name. Throughout whole proceeding not a word is spoken. Hence the name “Dumb Cake.” (If supper is served before 11:30, “Dumb Cake” should be reserved for one of the After- Supper Tests.)

TRUE-LOVER TEST

Two hazel-nuts are thrown into hot coals by maiden, who secretly gives a lover’s name to each. If one nut bursts, then that lover is unfaithful; but if it burns with steady glow until it becomes ashes, she knows that her lover is true. Sometimes it happens, but not often, that both nuts burn steadily, and then the maiden’s heart is sore perplexed.

WEB OF FATE

Long bright colored strings, of equal length are twined and intertwined to form a web.

Use half as many strings as there are guests.

Remove furniture from center of a large room—stretch a rope around the room, from corner to corner, about four feet from the floor. Tie one end of each string to the rope, half at one end and half at one side of the room; weave the strings across to the opposite end and side of the room and attach to rope. Or leave furniture in room and twine the strings around it.

Each guest is stationed at the end of a string and at a signal they begin to wind up the string until they meet their fate at the other end of it.

The lady and gentleman winding the same string will marry each other, conditions being favorable; otherwise they will marry someone else. Those who meet one of their own sex at the other end of the string will be old maids or bachelors.

The couple finishing first will be wedded first.

A prize may be given the lucky couple, also to the pair of old maids and the pair of bachelors finishing first.

THREADING A NEEDLE

Sit on round bottle laid lengthwise on floor, and try to thread a needle. First to succeed will be first married.

(More).

In the first chapter of his estimable volume The Book of Were-Wolves (1865), Sabine Baring-Gould outlines his project (emphasis mine):

In the following pages I design to investigate the notices of were-wolves to be found in the ancient writers of classic antiquity, those contained in the Northern Sagas, and, lastly, the numerous details afforded by the mediæval authors. In connection with this I shall give a sketch of modern folklore relating to Lycanthropy.

It will then be seen that under the veil of mythology lies a solid reality, that a floating superstition holds in solution a positive truth.

This I shall show to be an innate craving for blood implanted in certain natures, restrained under ordinary circumstances, but breaking forth occasionally, accompanied with hallucination, leading in most cases to cannibalism. I shall then give instances of persons thus afflicted, who were believed by others, and who believed themselves, to be transformed into beasts, and who, in the paroxysms of their madness, committed numerous murders, and devoured their victims.

The first few chapters of the book recount werewolf mythology in heavily archetypal terms: we’re talking Greek and Norse stuff here, really ancient stories that tap into primal-human-animal-instinct and so forth. Then there are a few chapters on Scandinavian werewolves (and other shapeshifters) that reminded me of William Vollmann’s marvelous saga The Ice-Shirt, a book that treats warriors shifting into bears as totally standard fare. The book then tackles “The Were-Wolf in the Middle Ages,” where Baring-Gould relies heavily on monks who seem to view their subject through the heady lens of supernaturalism. Baring-Gould weaves together these culturally disparate stories, citing a strong backlist of sources, and refraining from pointing out the obvious archetypal flavor that girds these tales.

It’s in Chapter VI, “A Chamber of Horrors,” that mythology and archetype give way to a kind of terrible realism. Perhaps this is simply an effect of records-keeping, of the vague fact that narratives and terms of the early Renaissance seem so much more accessible to us than, say, the terms of Scandinavian saga. In any case, the book takes on a horrific scope: the vagaries of myth give way to dates, names, places, witnesses, trials, verdicts. To go back to Baring-Gould’s intro, we see the “solid reality” under “the veil of mythology,” stripped away. Continue reading “Bolaño’s Werewolves”