Author: Biblioklept

No More Games — Benny Andrews

No More Games, 1970 by Benny Andrews (1930-2006)

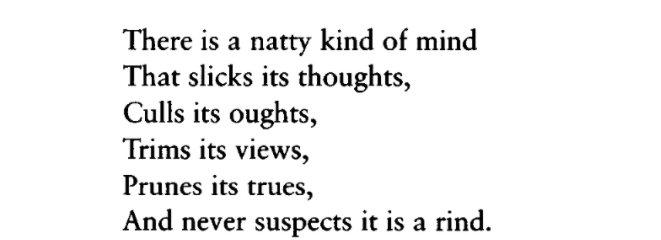

The Mind Is Its Own Place — Jennifer Packer

The Mind Is Its Own Place, 2020 by Jennifer Packer (b. 1984)

A review of William Melvin Kelley’s polyglossic postmodern novel Dunfords Travels Everywheres

William Melvin Kelley’s final novel Dunfords Travels Everywhere was published in 1970 to mixed reviews and then languished out of print for half a century. Formally and conceptually challenging, Dunfords contrasts strongly with the mannered modernism of Kelley’s first (and arguably most popular) novel A Different Drummer (1962). In A Different Drummer, Kelley offered the lucid yet Faulknerian tale of Caliban Tucker, a black Southerner who leads his people to freedom. The novel is naturalistic and ultimately optimistic. Kelley’s follow up, A Drop of Patience (1965), follows a similar naturalistic approach. By 1967 though, Kelley moved to a more radical style in his satire dem. In dem, Kelley enlarges his realism, injecting the novel with heavy doses of distortion. dem is angrier, more ironic and hyperbolic than the works that preceded it. Its structure is strange—not fragmented, exactly—but the narrative is parceled out in vignettes which the reader must synthesize himself. dem’s experimentation is understated, but its form—and its angry energy—point clearly towards Kelley’s most postmodern novel, Dunfords Travels Everywheres. Polyglossic, fragmented, and bubbling with aporia, Dunfords, now in print again, will no doubt baffle, delight, and divide readers today the same way it did fifty years ago.

Dunfords Travels Everywheres opens in a fictional European city. A group of American travelers meet for a softball game, only to learn that their president has been assassinated. They head to a cafe to console themselves. After some wine, the Americans toast their fallen president and begin singing “one of the two or three songs the people back home considered patriotic.” Chig Dunford, the sole black member of the travelers, refrains from singing, and when his patriotism is questioned and he is implored to sing, he explodes: “No, motherfucker!” The profane outburst alienates his companions, and Chig questions his language: “Where on earth had those words come from? He tried always to choose his words with care, to hold back anger until he found the correct words.”

It turns out that Chig’s motherfucker is a secret spell, a compound streetword that unlocks the dreamlanguage of Dunfords Travels Everywheres. After its incantation, Dunfords’ rhetoric pivots:

Witches oneWay tspike Mr. Chigyle’s Languish, n curryng him back tRealty, recoremince wi hUnmisereaducation. Maya we now go on wi yReconstruction, Mr. Chuggle? Awick now? Goodd, a’god Moanng agen everybubbahs n babys among you, d’yonLadys in front who always come vear too, days ago, dhisMorning We wddeal, in dhis Sagmint of Lecturian Angleash 161, w’all the daisiastrous effects, the foxnoxious bland of stimili, the infortunelessnesses of circusdances which weak to worsen the phistorystematical intrafricanical firmly structure of our distinct coresins: The Blafringro‐Arumericans.

So Chig, who has told us he looks always to choose the “correct words,” comes through languish/language “back tRealty,” to commence again his education and reconstruction. He’s given new names Mr. Chuggle and Mr. Chigyle. Renaming becomes a motif in the novel. Here in the dreamworld—or is it reality, as Chig’s dreamteachers seem to suggest?—there are multiple Chigs, a plot point emphasized in the novel’s strange title. Dunfords Travels Everwheres seems initially ungrammatical—shouldn’t the title be something like Dunford Travels Everywhere or Dunford’s Travels Everywhere? one wonders at first. Packed into the title though is a key to the novel’s meaning: There are multiple Dunfords, multiple travels, and, perhaps most significantly, multiple everywheres. The novel’s title also points to two of its reference points, Swift’s satire Gulliver’s Travels and James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (famously absent an apostrophe).

Many readers will undoubtedly recognize the influence of Joyce’s Wake in Kelley’s so-called experimental passages. And while Finnegans is clearly an inspiration, Kelley’s prose has a different flavor—more creole, more pidgin, more Afrocentric than Joyce’s synthesis of European tongues. The passages can be difficult if you want them to be, or you can simply float along with them. I found myself reading them aloud, letting my ear make connections that my eyes might have missed. I’ll also readily concede that there’s a ton of stuff in the passages that I found inscrutable. Sometimes its best to go with the flow.

And where does that flow go? The title promises everywheres, and the central plot of Dunfords might best be understood as a consciousness traveling though an infinite but subtly shifting loop. Chig Dunford slips in and out of the dreamworld, traveling through Europe and then back to America. The final third of the novel is a surreal transatlantic sea voyage that darkly mirrors the Euro-American slave trade. It’s also a shocking parody of America’s sexual and racial hang-ups. It’s also really confusing at times, calling into question what elements of the book are “real” and what elements are “dream.” In my estimation though, the distinction doesn’t matter in Dunfords. All that matters is the language.

The language—specifically the so-called experimental language—transports characters and readers alike. We’re first absorbed into the dreamlanguage on page fifty, and swirl around in it for a dozen more pages before arriving somewhere far, far away from Chig Dunford in the European cafe. In the course of a paragraph, the narrative moves from linguistic surrealism to lucid realism to start a new thread in the novel:

Now will ox you, Mr. Chirlyle? Be your satisfreed from the dimage of the Muffitoy? Heave you learned your caughtomkidsm? Can we send you out on your hownor? Passable. But proveably not yetso tokentinue the candsolidation of the initiatory natsure of your helotionary sexperience, le we smiuve for illustration of chiltural rackage on the cause of a Hardlim denteeth who had stopped loving his wife. Before he stopped loving her, he had given her a wonderful wardrobe, a brownstone on the Hill, and a cottage on Long Island. Unfortunately, her appetite remained unappeased. She wanted one more thing—a cruise around the world. And so he asked her for a divorce.

This Harlem dentist employs Carlyle Bedlow, a minor but important character in dem, to seduce his wife. Bedlow then becomes a kind of twin to Chig, as the novel shifts between Chig’s story and Bedlow’s, always mediated via dreamlanguage. Bedlow’s adventures are somewhat more comical than Chig’s (he even outfoxes the Devil), and although he’s rooted in Harlem, he’s just as much an alien to his own country as Chig is.

Dunfords’ so-called experimental passages are a linguistic bid to overcome that alienation. While they clearly recall the language of Finnegans Wake, they also point to another of Joyce’s novels, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Kelley pulls the first of Dunfords’ three epigraphs from Joyce’s novel:

The language in which we are speaking is his before it is mine…I cannot speak or write these words without unrest of spirit. His language, so familiar and so foreign, will always be for me an acquired speech…My soul frets in the shadow of his language.

In Portrait, Stephen Dedalus realizes that he is linguistically inscribed in a conqueror’s tongue, but he will work to forge that language into something capable of expressing the “uncreated conscience of [his] race.” The linguistic play of Dunfords finds Kelley forging his own language, his own tongue of resistance.

The dreamlanguage overtakes the final pages of Dunfords, melting African folklore with Norse myths into something wholly new, sticky, rich. There’s more than a dissertation’s worth of parsing in those last fifteen pages. I missed in them than I caught, but I don’t mind being baffled, especially when the book’s final paragraph is so lovely:

You got aLearn whow you talking n when tsay whit, man. What, man? No, man. Soaree! Yes sayd dIt t’me too thlow. Oilready I vbegin tshift m Voyace. But you llbob bub aGain. We cdntlet aHabbub dfifd on Fur ever, only fo waTerm aTime tpickcip dSpyrate by pinchng dSkein. In Side, out! Good-bye, man: Good-buy, man. Go odd-buy Man. Go Wood, buy Man. Gold buy Man. MAN!BE!GOLD!BE!

You’ve got to learn how/who you are talking to and when to say what/wit, right? The line “Oilready I vbegin tshift m Voyace” points to shifting voices, shifting consciousnesses , but also the voice as the voyage, the tongue as a traveler.

The passages I’ve shared above should give you a sense of whether or not the ludic prose of Dunfords is your particular flavor of choice. Initial reviews were critical of Kelley’s choices, including both the novel’s language and its structure. It received two contemporary reviews in The New York Times; in the first, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt praised Kelley’s use of “a black form of the dreamlanguage of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake…to escape the strictures of the conventional (white) novel,” but concluded that “there are many things in the novel that don’t work, that seem curiously cryptic and incomplete.” Playwright Clifford Mason was far harsher in his review a few weeks later, writing that “the experimental passages offer little to justify the effort needed to decipher them. The endless little word games can only be called tiresome.”

I did not find the word games endless, little, or tiring, but I’m sure there are many folks who would agree with Mason’s sentiments from five decades ago. While American culture has slowly been catching up to Kelley’s politics and aesthetics, his dreamlanguage will no doubt alienate many contemporary readers who prefer their prose hardened into lucid meaning. Kelley understood the power of language shift. He coined the word “woke” in a 1962 New York Times piece that both lamented and celebrated the way that black language was appropriated by white folks only to be reinvented again by by black speakers. In some ways, Dunfords is his push into a language so woke it appears to be the language of sleep. But the subconscious talkers in Dunfords don’t babble. Their words pack—perhaps overpack—meaning.

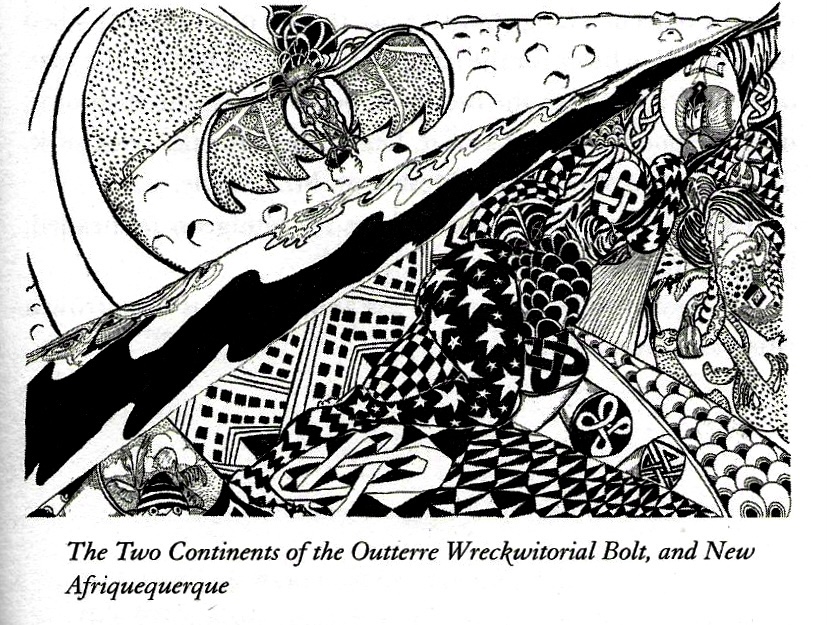

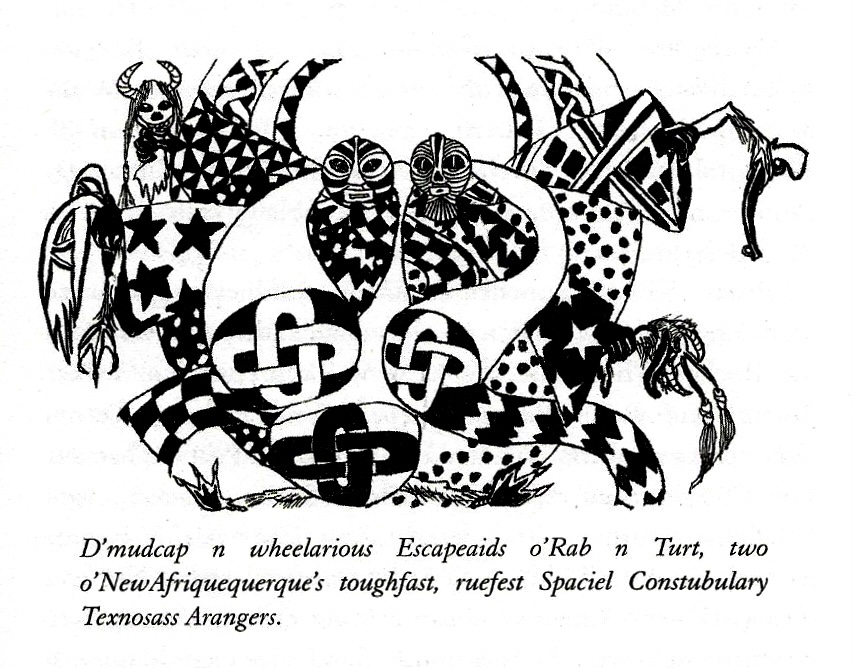

The overpacking makes for a difficult read at times. Readers interested in Kelley—an overlooked writer, for sure—might do better to start with A Different Drummer or dem, both of which are more conventional, both in prose and plot. Thankfully, Anchor Books has reprinted all five of Kelley’s books, each with new covers by Kelley’s daughter. This new edition of Dunfords also features pen-and-ink illustrations that Kelley commissioned from his wife Aiki. These illustrations, which were not included in the novel’s first edition in 1970, add to the novel’s surreal energy. I’ve included a few in this review.

Dunfords Travels Everywheres is a challenging, rich, weird read. At times baffling, it’s never boring. Those who elect to read it should go with the flow and resist trying to impose their own logical or rhetorical schemes on the narrative. It’s a fantastic voyage—or Voyace?—check it out.

[Ed note–Biblioklept first published this review in October 2020.]

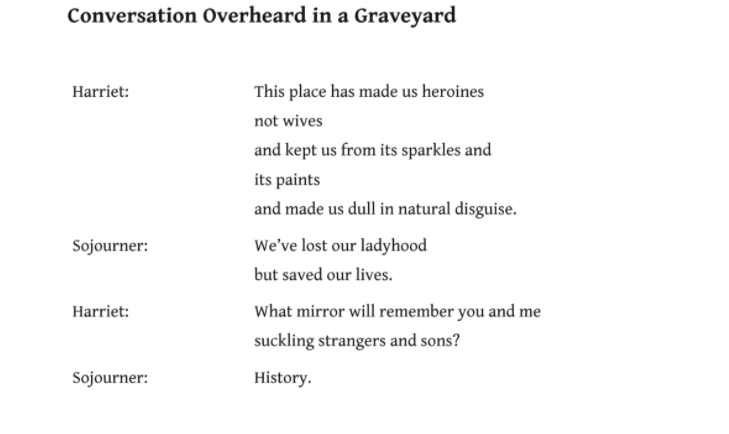

“Conversation Overheard in a Graveyard” — Lucille Clifton

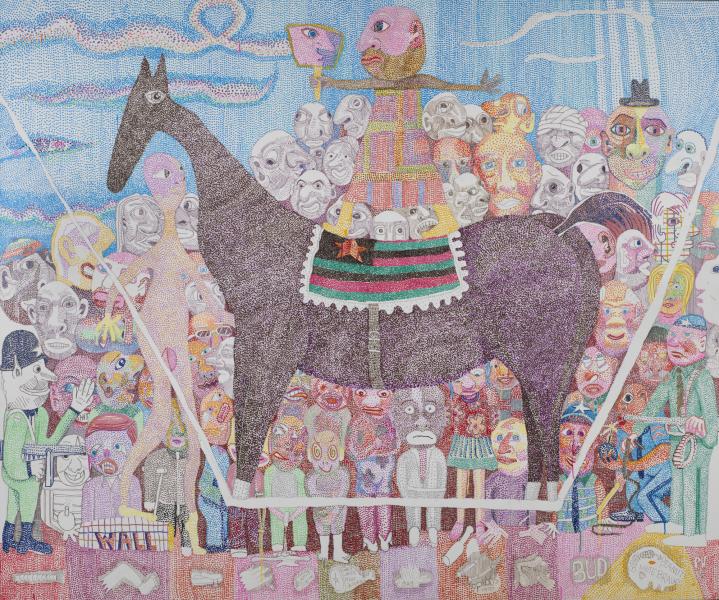

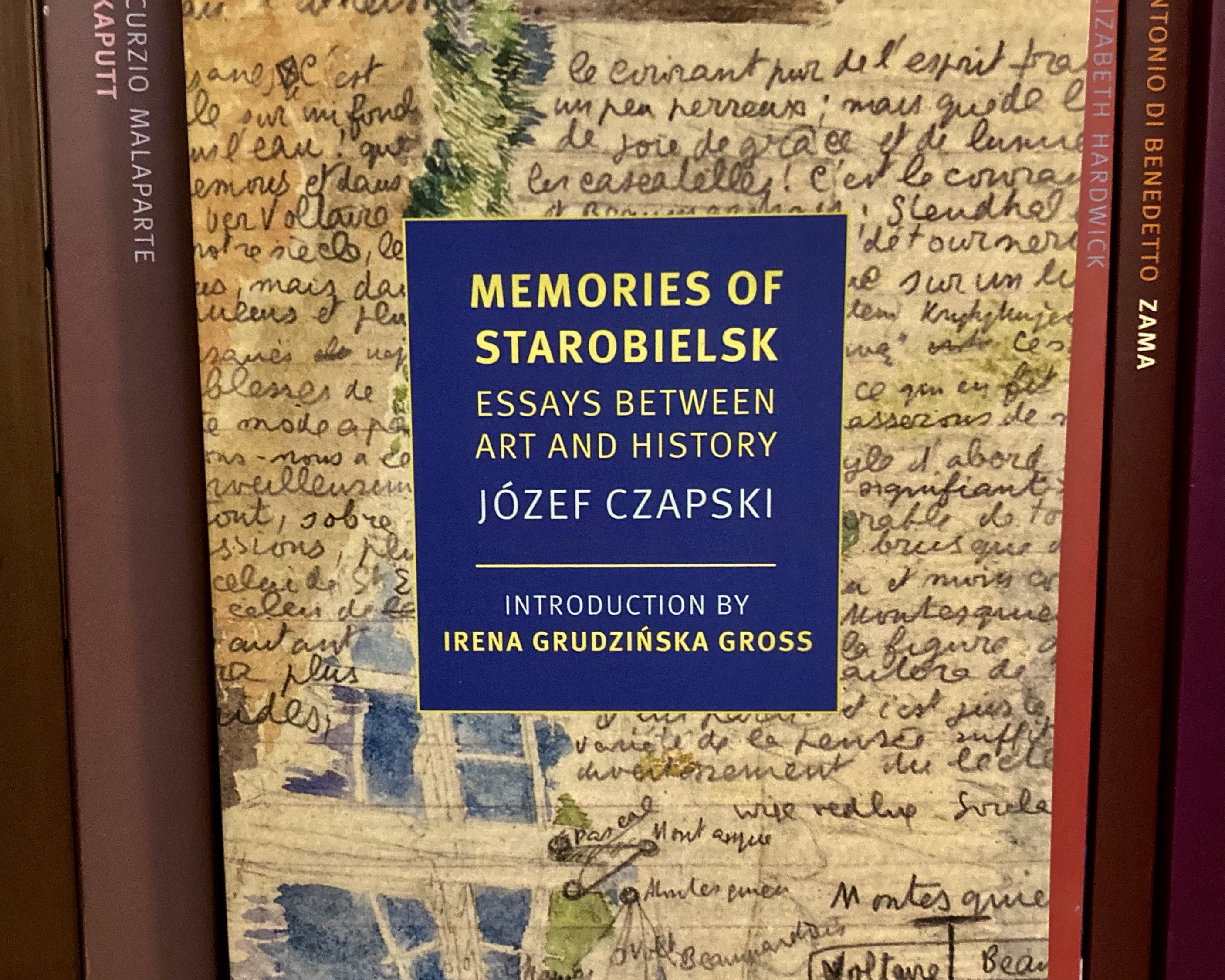

A Foolish Trick — Peter Williams

A Foolish Trick, 2018 by Peter Williams (1952-2021)

Ignorance and Bigotry | From William Blades’ The Enemies of Books

“Ignorance and Bigotry”

from

IGNORANCE, though not in the same category as fire and water, is a great destroyer of books. At the Reformation so strong was the antagonism of the people generally to anything like the old idolatry of the Romish Church, that they destroyed by thousands books, secular as well as sacred, if they contained but illuminated letters. Unable to read, they saw no difference between romance and a psalter, between King Arthur and King David; and so the paper books with all their artistic ornaments went to the bakers to heat their ovens, and the parchment manuscripts, however beautifully illuminated, to the binders and boot makers.

There is another kind of ignorance which has often worked destruction, as shown by the following anecdote, which is extracted from a letter written in 1862 by M. Philarete Chasles to Mr. B. Beedham, of Kimbolton:—

“Ten years ago, when turning out an old closet in the Mazarin Library, of which I am librarian, I discovered at the bottom, under a lot of old rags and rubbish, a large volume. It had no cover nor title-page, and had been used to light the fires of the librarians. This shows how great was the negligence towards our literary treasure before the Revolution; for the pariah volume, which, 60 years before, had been placed in the Invalides, and which had certainly formed part of the original Mazarin collections, turned out to be a fine and genuine Caxton.”

I saw this identical volume in the Mazarin Library in April, 1880. It is a noble copy of the First Edition of the “Golden Legend,” 1483, but of course very imperfect. Continue reading “Ignorance and Bigotry | From William Blades’ The Enemies of Books”

“Unsuspecting” — Jean Toomer

Lavender Embrace — Jordan Casteel

Lavender Embrace, 2018 by Jordan Casteel (b. 1989)

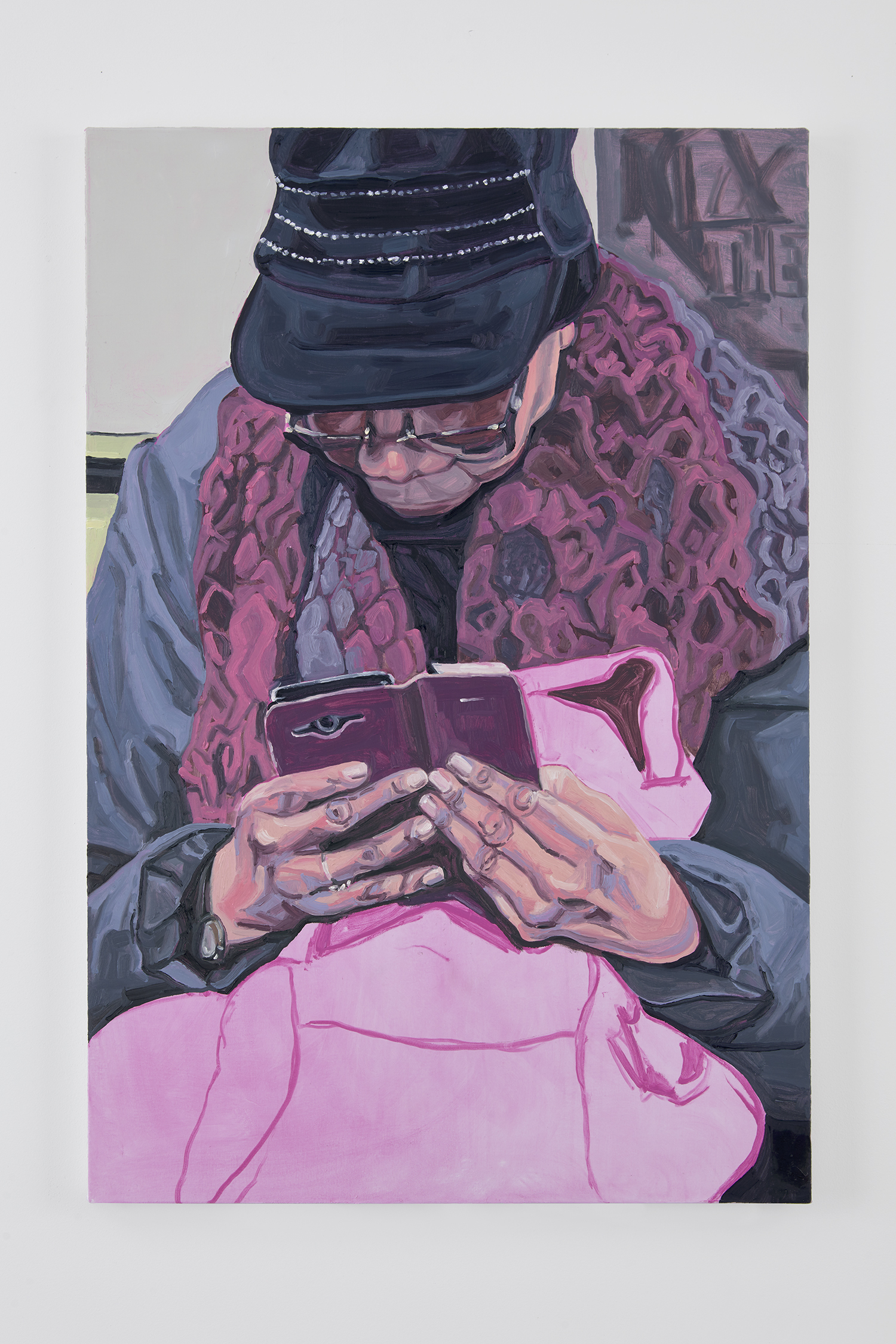

Józef Czapski’s Memories of Starobielsk (Book acquired, 7 Feb. 2022)

Józef Czapski’s Memories of Starobielsk: Essays between Art and History is forthcoming from NYRB in Alissa Valles’s translation. Their blurb:

Interned with thousands of Polish officers in the Soviet prisoner-of-war camp at Starobielsk in September 1939, Józef Czapski was one of a very small number to survive the massacre in the forest of Katyń in April 1940. Memories of Starobielsk portrays these doomed men, some with the detail of a finished portrait, others in vivid sketches that mingle intimacy with respect, as Czapski describes their struggle to remain human under hopeless circumstances. Essays on art, history, and literature complement the memoir, showing Czapski’s lifelong engagement with Russian culture. The short pieces on painting that he wrote while on a train traveling from Moscow to the Second Polish Army’s strategic base in Central Asia stand among his most lyrical and insightful reflections on art.

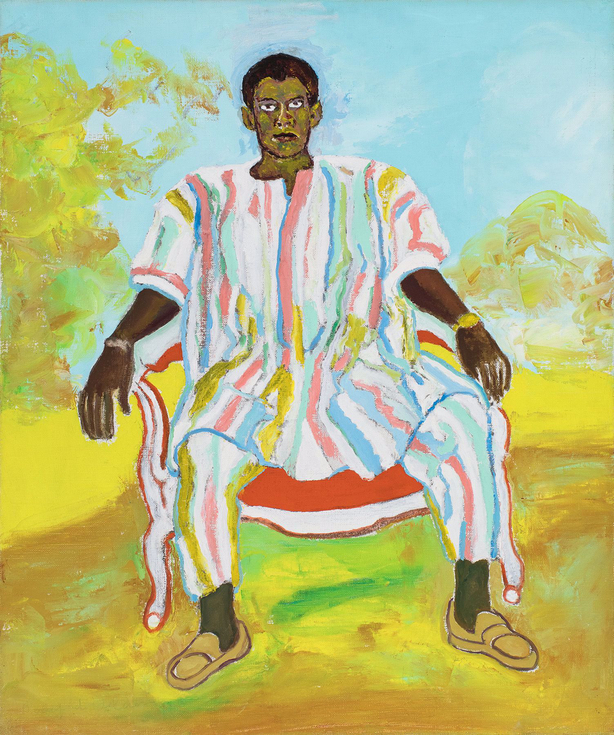

Untitled — Beauford Delaney

Untitled (Man in African Dress), 1972 by Beauford Delaney (1901–1979)

A review of Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down, Ishmael Reed’s syncretic Neo-HooDoo revenge Western

Ishmael Reed’s second novel Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down tells the story of the Loop Garoo Kid, a “desperado so onery he made the Pope cry and the most powerful of cattlemen shed his head to the Executioner’s swine.”

The novel explodes in kaleidoscopic bursts as Reed dices up three centuries of American history to riff on race, religion, sex, and power. Unstuck in time and unhampered by geographic or technological restraint, historical figures like Lewis and Clark, Thomas Jefferson, John Wesley Harding, Groucho Marx, and Pope Innocent (never mind which one) wander in and out of the narrative, supplementing its ironic allegorical heft. These minor characters are part of Reed’s Neo-HooDoo spell, ingredients in a Western revenge story that is simultaneously comic and apocalyptic in its howl against the dominant historical American narrative. Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down is a strange and marvelous novel, at once slapstick and deadly serious, exuberant in its joy and harsh in its bitterness, close to 50 years after its publication, as timely as ever.

After the breathless introduction of its hero the Loop Garoo Kid, Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down initiates its plot. Loop’s circus troupe arrives to the titular city Yellow Back Radio (the “nearest town Video Junction is about fifty miles away”), only to find that the children of the town, “dressed in the attire of the Plains Indians,” have deposed the adults:

We chased them out of town. We were tired of them ordering us around. They worked us day and night in the mines, made us herd animals harvest the crops and for three hours a day we went to school to hear teachers praise the old. Made us learn facts by rote. Lies really bent upon making us behave. We decided to create our own fiction.

The children’s revolutionary, anarchic spirit drives Reed’s own fiction, which counters all those old lies the old people use to make us behave.

Of course the old—the adults—want “their” land back. Enter that most powerful of cattlemen, Drag Gibson, who plans to wrest the land away from everyone for himself. We first meet Drag “at his usual hobby, embracing his property.” Drag’s favorite property is a green mustang,

a symbol for all his streams of fish, his herds, his fruit so large they weighed down the mountains, black gold and diamonds which lay in untapped fields, and his barnyard overflowing with robust and erotic fowl.

Drag loves to French kiss the horse, we’re told. Oh, and lest you wonder if “green” here is a metaphor for, like, new, or inexperienced, or callow: No. The horse is literally green (“turned green from old nightmares”). That’s the wonderful surreal logic of Reed’s vibrant Western, and such details (the novel is crammed with them) make Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down a joy to read.

Where was I? Oh yes, Drag Gibson.

Drag—allegorical stand-in for Manifest Destiny, white privilege, capitalist expansion, you name it—Drag, in the process of trying to clear the kids out of Yellow Back Radio, orders all of Loop’s troupe slaughtered.

The massacre sets in motion Loop’s revenge on Drag (and white supremacy in general), which unfolds in a bitter blazing series of japes, riffs, rants, and gags. (“Unfolds” is the wrong verb—too neat. The action in Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down is more like the springing of a Jack-in-the-box).

Loop goes about obtaining his revenge via his NeoHooDoo practices. He calls out curses and hexes, summoning loas in a lengthy prayer. Loop’s spell culminates in a call that goes beyond an immediate revenge on Drag and his henchmen, a call that moves toward a retribution for black culture in general:

O Black Hawk American Indian houngan of Hoo-Doo please do open up some of these prissy orthodox minds so that they will no longer call Black People’s American experience “corrupt” “perverse” and “decadent.” Please show them that Booker T and MG’s, Etta James, Johnny Ace and Bojangle tapdancing is just as beautiful as anything that happened anywhere else in the world. Teach them that anywhere people go they have experience and that all experience is art.

So much of Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down is turning all experience into art. Reed spins multivalent cultural material into something new, something arguably American. The title of the novel suggests its program: a breaking-down of yellowed paperback narratives, a breaking-down of radio signals. Significantly, that analysis, that break-down, is also synthesized in this novel into something wholly original. Rhetorically, Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down evokes flipping through paperbacks at random, making a new narrative; or scrolling up and down a radio dial, making new music from random bursts of sound; or rifling through a stack of manic Sunday funnies to make a new, somehow more vibrant collage.

Perhaps the Pope puts it best when he arrives late in the novel. (Ostensibly, the Pope shows up to put an end to Loop’s hexing and vexing of the adult citizenry—but let’s just say the two Holy Men have a deeper, older relationship). After a lengthy disquisition on the history of hoodoo and its genesis in the Voudon religion of Africa (“that strange continent which serves as the subconscious of our planet…shaped so like the human skull”), the Pope declares that “Loop Garoo seems to be practicing a syncretistic American version” of the old Ju Ju. The Pope continues:

Loop seems to be scatting arbitrarily, using forms of this and that and adding his own. He’s blowing like that celebrated musician Charles Yardbird Parker—improvising as he goes along. He’s throwing clusters of demon chords at you and you don’t know the changes, do you Mr. Drag?

The Pope here describes Reed’s style too, of course (which is to say that Reed is describing his own style, via one of his characters. The purest postmodernism). The apparent effortlessness of Reed’s improvisations—the prose’s sheer manic energy—actually camouflages a tight and precise plot. I was struck by how much of Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down’s apparent anarchy resolves into a bigger picture upon a second reading.

That simultaneous effortlessness and precision makes Reed’s novel a joy to jaunt through. Here is a writer taking what he wants from any number of literary and artistic traditions while dispensing with the forms and tropes he doesn’t want and doesn’t need. If Reed wants to riff on the historical relations between Indians and African-Americans, he’ll do that. If Reed wants to assess the relative values of Thomas Jefferson as a progressive figure, he’ll do that. If Reed wants to attack his neo-social realist critics, he’ll do that. If Reed wants to critique the relationship between militarism and science, he’ll do that. If Reed wants to tell some really dirty jokes about a threesome, he’ll do that. And you can bet if he wants some ass-kicking Amazons to show up at some point, they’re gonna show.

And it’s a great show. Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down begins with the slaughter of a circus troupe before we get to see their act. The real circus act is the novel itself, filled with orators and showmen, carnival barkers and con-artists, pistoleers and magicians. There’s a manic glee to it all, a glee tempered in anger—think of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, or Thomas Pynchon’s zany rage, or Robert Downey Sr.’s satirical film Putney Swope.

Through all its anger, Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down nevertheless repeatedly affirms the possibility of imagination and creation—both as cures and as hexes. We have here a tale of defensive and retaliatory magic. Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down is the third novel of Reed’s novels I’ve read (after Mumbo Jumbo and The Free-Lance Pallbearers), and my favorite thus far. Frankly, I needed the novel right now in a way that I didn’t know that I needed it until I read it; the contemporary novel I tried to read after it felt stale and boring. So I read Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down again. The great gift here is that Reed’s novel answers to the final line of Loop’s prayer to the Loa: “Teach them that anywhere people go they have experience and that all experience is art.” Like the children of Yellow Back Radio, Reed creates his own fiction, and invites us to do the same. Very highly recommended.

[Ed. note — Biblioklept first published this review in February of 2017.]

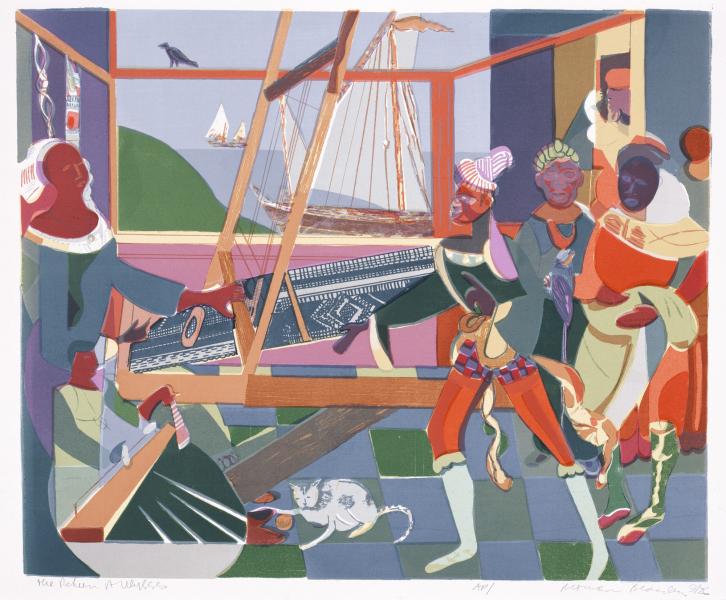

Return of Ulysses — Romare Bearden

Return of Ulysses, 1976 by Romare Bearden (1911-1988)

Saturday’s Child — Charles White

Saturday’s Child, 1965 by Charles White (1918-1979)

Slow Decay | From William Blades’ The Enemies of Books

“Dust and Neglect”

from

DUST upon Books to any extent points to neglect, and neglect means more or less slow Decay.

A well-gilt top to a book is a great preventive against damage by dust, while to leave books with rough tops and unprotected is sure to produce stains and dirty margins.

In olden times, when few persons had private collections of books, the collegiate and corporate libraries were of great use to students. The librarians’ duties were then no sinecure, and there was little opportunity for dust to find a resting-place. The Nineteenth Century and the Steam Press ushered in a new era. By degrees the libraries which were unendowed fell behind the age, and were consequently neglected. No new works found their way in, and the obsolete old books were left uncared for and unvisited. I have seen many old libraries, the doors of which remained unopened from week’s end to week’s end; where you inhaled the dust of paper-decay with every breath, and could not take up a book without sneezing; where old boxes, full of older literature, served as preserves for the bookworm, without even an autumn “battue” to thin the breed. Occasionally these libraries were (I speak of thirty years ago) put even to vile uses, such as would have shocked all ideas of propriety could our ancestors have foreseen their fate.

I recall vividly a bright summer morning many years ago, when, in search of Caxtons, I entered the inner quadrangle of a certain wealthy College in one of our learned Universities. The buildings around were charming in their grey tones and shady nooks. They had a noble history, too, and their scholarly sons were (and are) not unworthy successors of their ancestral renown. The sun shone warmly, and most of the casements were open. From one came curling a whiff of tobacco; from another the hum of conversation; from a third the tones of a piano. A couple of undergraduates sauntered on the shady side, arm in arm, with broken caps and torn gowns—proud insignia of their last term. The grey stone walls were covered with ivy, except where an old dial with its antiquated Latin inscription kept count of the sun’s ascent. The chapel on one side, only distinguishable from the “rooms” by the shape of its windows, seemed to keep watch over the morality of the foundation, just as the dining-hall opposite, from whence issued a white-aproned cook, did of its worldly prosperity. As you trod the level pavement, you passed comfortable—nay, dainty—apartments, where lace curtains at the windows, antimacassars on the chairs, the silver biscuit-box and the thin-stemmed wine-glass moderated academic toils. Gilt-backed books on gilded shelf or table caught the eye, and as you turned your glance from the luxurious interiors to the well-shorn lawn in the Quad., with its classic fountain also gilded by sunbeams, the mental vision saw plainly written over the whole “The Union of Luxury and Learning.”

Continue reading “Slow Decay | From William Blades’ The Enemies of Books”

Americans love being conned (Ishmael Reed)

It was Bo Shmo and the neo-social realist gang. They rode to this spot from their hideout in the hills. Bo Shmo leaned in his saddle and scowled at Loop, whom he considered a deliberate attempt to be obscure. A buffoon an outsider and frequenter of sideshows.

Bo Shmo was dynamic and charismatic as they say. He made a big reputation in the thirties, not having much originality, by learning to play Hoagland Howard Carmichael’s “Buttermilk Sky” backwards. He banged the piano and even introduced some novel variations such as sliding his rump across the black and whites for that certain effect.

People went for it. It was an all the newspapers. He traveled from coast to coast exhibiting his ass and everything was fine until the real Hoagland Howard Carmichael (the real one) showed up and went for Bo Shmo’s goat. He called him a lowdown patent thief and railed him out of town. You would think that finding themselves duped, the impostor’s fans would demand his hide. Not so, Americans love being conned if you can do it in a style that is both grand and entertaining. Consider P.T. Barnum’s success, Semple McPherson and other notables. A guy who rigs aluminum prices can get himself introduced by Georgie Jessel at 100 dollars a plate but stealing a can of beer can get you iced.

So sympathetic Americans sent funds to Bo Shmo which he used to build one huge neo-social realist Institution in the Mountains. Wagon trains of neo-social realist composers writers and painters could be seen winding up its path.

From Ishmael Reed’s 1969 novel Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down, which I am loving the hell out of.

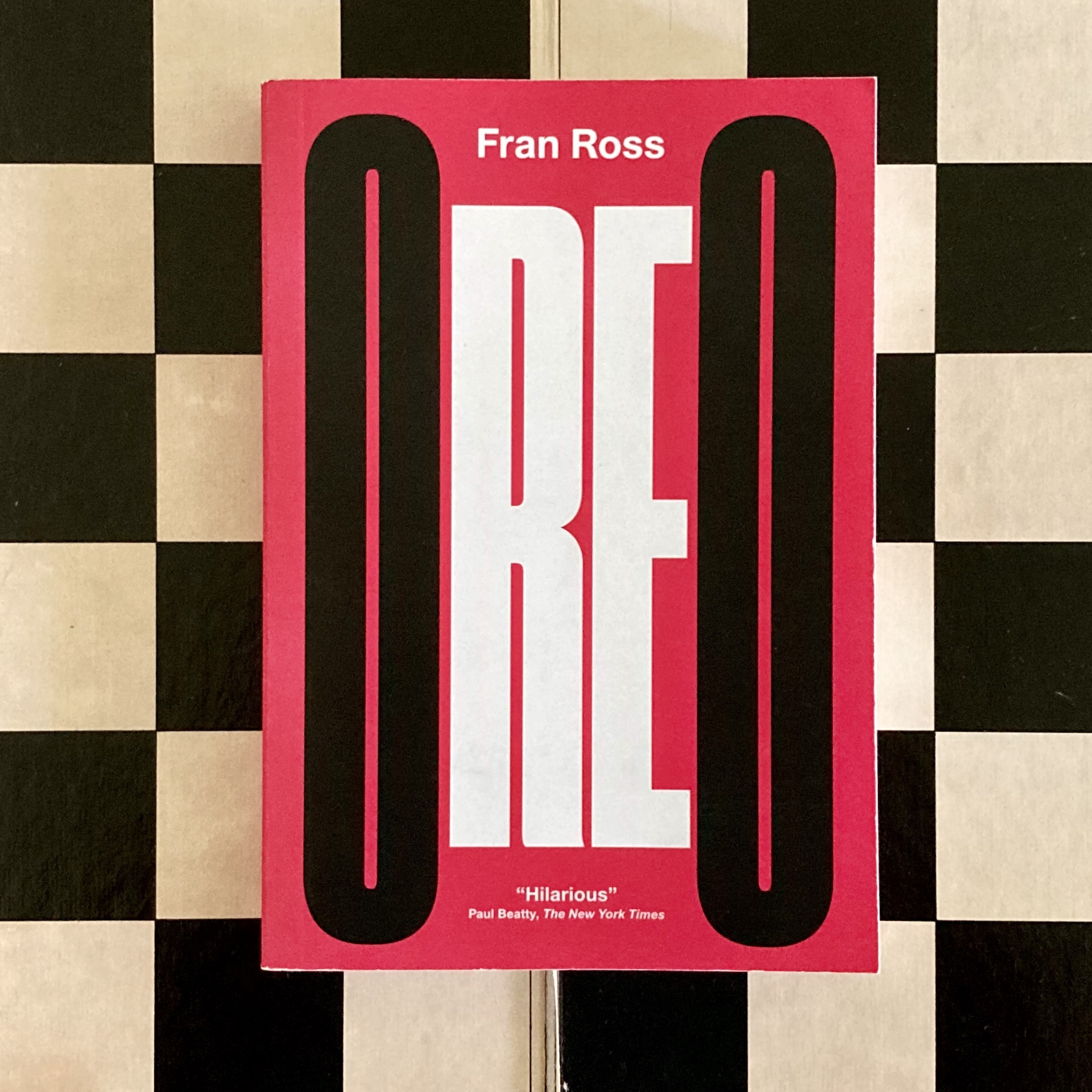

On Fran Ross’s postmodern picaresque novel Oreo

Fran Ross’s 1974 novel Oreo is an overlooked masterpiece of postmodern literature, a delicious satire of the contemporary world that riffs on race, identity, patriarchy, and so much more. Oreo is a pollyglossic picaresque, a metatextual maze of language games, raps and skits, dinner menus and vaudeville routines. Oreo’s rush of language is exuberant, a joyful metatextual howl that made me laugh out loud. Its 212 pages galloped by, leaving me wanting more, more, more.

Oreo is Ross’s only novel. It was met with a handful of confused reviews upon its release and then summarily forgotten until 2000, when Northeastern University Press reissued the novel with an introduction by UCLA English professor Harryette Mullen. (New Directions offered a wider release with a 2015 reissue, including Mullen’s introduction as an afterword.)

Mullen gives a succinct summary of Oreo in the opening sentence of her 2002 essay “‘Apple Pie with Oreo Crust’: Fran Ross’s Recipe for an Idiosyncratic American Novel“:

In Fran Ross’s 1974 novel Oreo, the Greek legend of Theseus’ journey into the Labyrinth becomes a feminist tall tale of a young black woman’s passage from Philadelphia to New York in search of her white Jewish father.

Mullen goes on to describe Oreo as a novel that “explores the heterogeneity rather than the homogeneity of African Americans.”

Oreo’s ludic heterogeneity may have accounted for its near-immediate obscurity. Ross’s novel celebrates hybridization and riffs–both in earnestness and irony—on Western tropes and themes that many writers of the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and ’70s specifically rejected.

Indeed, Oreo still feels ahead of its time, or out of its time, as novelist Danzy Senna repeatedly notes in her introduction to the New Directions reissue. Senna points out that “Oreo resists the unwritten conventions that still exist for novels written by black women today,” and writes that Ross’s novel “feels more in line stylistically, aesthetically, with Thomas Pynchon and Kurt Vonnegut than with Sonia Sanchez and Ntzoke Shange.”

In his review of Oreo, novelist Marlon James also posits Ross’s place with the postmodernists, suggesting that “maybe Ross is closer in spirit to the writers in the 70s who managed to make this patchwork sell,” before wryly noting, “Of course they were all white men: Vonnegut, Barth, Pynchon, and so on.”

Of course they were all white men. And perhaps this is why Oreo languished out of print so long. Was it erasure? Neglect? Institutional racism and sexism in publishing and literary criticism? Or just literal ignorance?

In any case, Ross belongs on the same postmodern shelf with Gaddis, Pynchon, Barth, Reed, and Coover. Oreo is a carnivalesque, multilingual explosion of the slash we might put between high and low. It’s a metatextual novel that plays zanily with the plasticity of its own form. Like Coover, Elkin, and Barthelme, Ross’s writing captures the spirit of mass media; Oreo is forever satirizing commercials, television, radio, film (and capitalism in general).

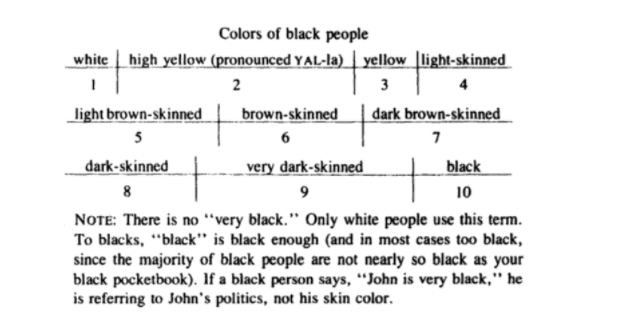

Ross plays with the page as well, employing quizzes, menus, and charts into the text, like this one, from the novel’s third page:

Oreo won me over with the postmodern paragraph that followed this chart, which I’ll share in full:

A word about weather

There is no weather per se in this book. Passing reference is made to weather in a few instances. Assume whatever season you like throughout. Summer makes the most sense in a book of this length. That way, pages do not have to be used up describing people taking off and putting on overcoats.

What happens in Oreo? Well, it’s a picaresque, sure, but it goes beyond, as Ralph Ellison put it, being “one of those pieces of writing which consists mainly of one damned thing after another sheerly happening.” (Although there are plenty of damned things happening, sheerly or otherwise, after each other.)

Oreo is a mock-epic, a satirical quest for the titular Oreo to discover the “secret of her birth,” using clues left by her white Jewish father who, like her mother, has departed. All sorts of stuff happens along the way–run ins with rude store clerks, attempted muggings, rhyming little people with a psychopathic son camping in the park, a short voice acting career, a soiree with a “rothschild of rich people,” a witchy stepmother, and a memorable duel with a pimp. (And more, more, more.)

Throughout it all, Oreo shines as a cartoon superhero, brave, impervious, adaptable, and full of wit—as well as WIT (Oreo’s self-invented “system of self- defense [called] the Way of the Interstitial Thrust, or WIT.” In “a state of extreme concentration known as hwip-as [Oreo could] engage any opponent up to three times her size and weight and whip his natural ass.)

Indeed, as Oreo’s uncle declares, “She sure got womb, that little mother…She is a ball buster and a half,” underscoring the novel’s feminist themes as well as its plasticity of language. Here “womb” becomes a substitution for “balls,” a symbol of male potency busted in the next sentence. This ironic inversion might serve as a synecdoche for Oreo’s entire quest to find her father, a mocking rejoinder to patriarchy. As Oreo puts it, quite literally: “I am going to find that motherfucker.”

Find that motherfucker she does and—well, I won’t spoil any more. Instead, I implore you to check out Oreo, especially if you’re a fan of all those (relatively) famous postmodernist American novels of the late twentieth century. I wish someone had told me to read Oreo ages ago, but I’m thankful I read it now, and I look forward to reading it again. Very highly recommended.

[Ed. note — Biblioklept first published this review in July of 2020.]