It is not a bad problem to have to have a big ole stack of big boys stacked up, waiting to read, but I nevertheless continue to feel anxiety as the stack grows and I head into a new semester, knowing that my reading for work—student papers of course, but also all the other stuff, the rereads of ringers I can’t give up, the new reads I continue to dedicate myself to incorporating into a syllabus, cursing myself when I’m not sure how to do what I think I want to do with them, etc.—but yeah, it’s the knowing that work-based reading will dominate my eyes and brain, both of which have grown duller, slower, and more easily-wearied over the last two years (and I have, after forty-one years of perfect eyesight, taken up glasses to my face to read finer print), and that I will find myself without the reserves to jump into the big books like I used to (I fall asleep sooner too these days–but also wake up sooner too, and do dedicated some of those early morning minutes to reading).

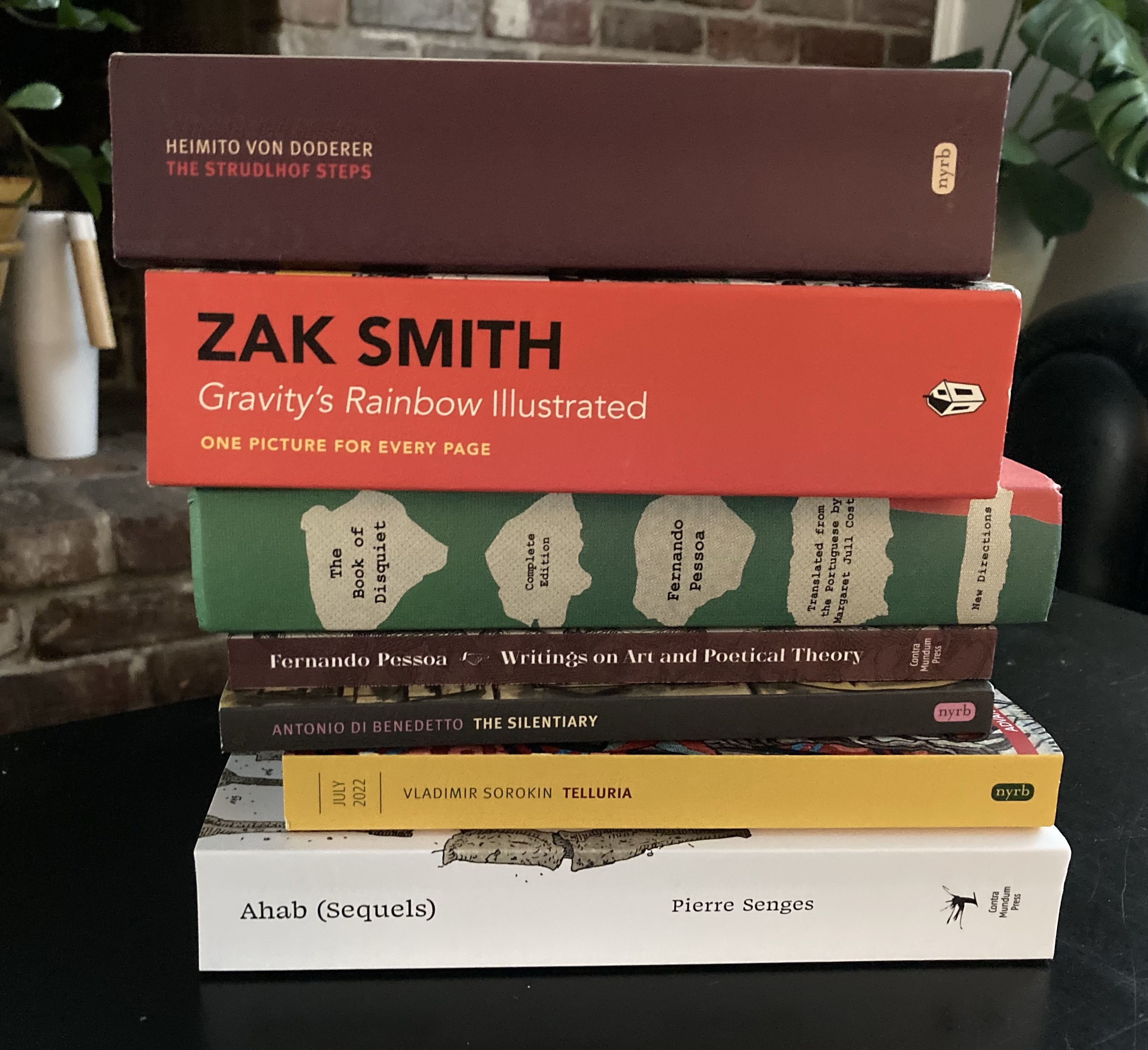

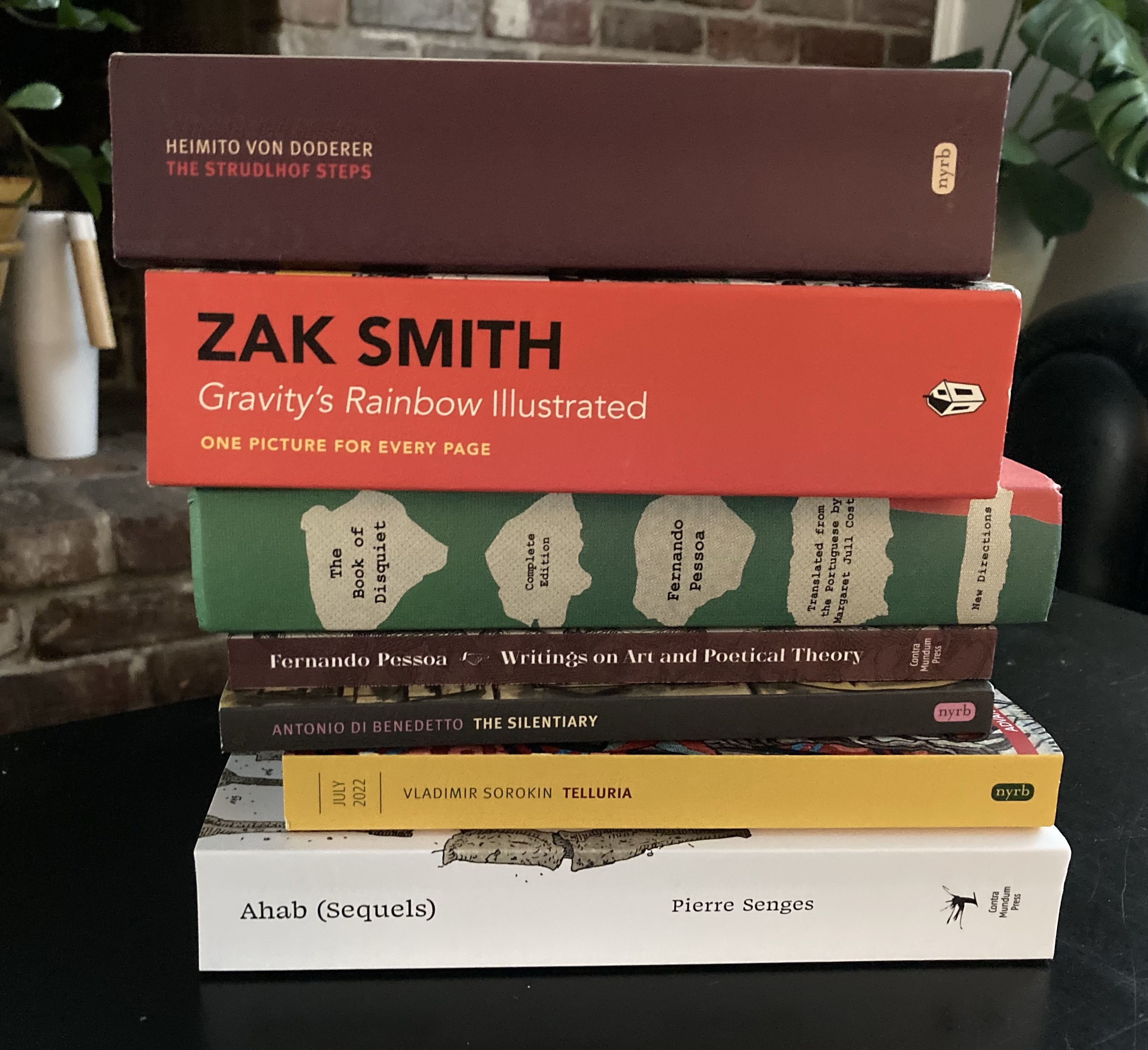

Heimito von Doderer’s The Strudlhof Steps is (translation by Vincent Kling) is one of a few NYRB titles on my list. I’ve jumped into it a few times and I can tell it’s a big deal—maybe something revelatory to me, a big mash of consciousness like Alfred Döblin’s 1929 novel Berlin Alexanderplatz. But other books keep showing up.

Or, really, I keep picking up other books, like Zak Smith’s Gravity’s Rainbow Illustrated, almost eight hundred pictures to go with Thomas Pynchon’s novel. I’ve paged through it, but the anxiety here is the realization that I want to read Gravity’s Rainbow again, which will make me go insane.

The two by Pessoa cause me anxiety for other reasons. I’m pretty sure I will never finish The Book of Disquiet (in translation by Margaret Jull Costa). It’s smart at times, but it’s not really a novel—the catch is the protagonist’s consciousness. And the protagonist often needs a big kick in the ass. Disquiet will riff out some lovely little missives, and then whine a bit. Not my favorite flavor. And yet I feel like I can’t tangle with Writings on Art and Poetical Theory without engaging Pessoa’s aesthetic firsthand (or, really, mediated through translators and editors).

Pessoa’s Writings is published by Contra Mundum, as is Pierre Senges’ Ahab (Sequels) (translation by Jacob Siefring and Tegan Raleigh). I made a bit of dent of the book, but then took a slimmer volume with me on a vacation to some Smoky Mountains. I read Alan Garner’s novel Red Shift there in two or three days and loved it and failed to write about it here. (I am sometimes astounded that for a few years in very early thirties I somehow wrote about every book I read on this blog.) Maybe spring for Ahab.

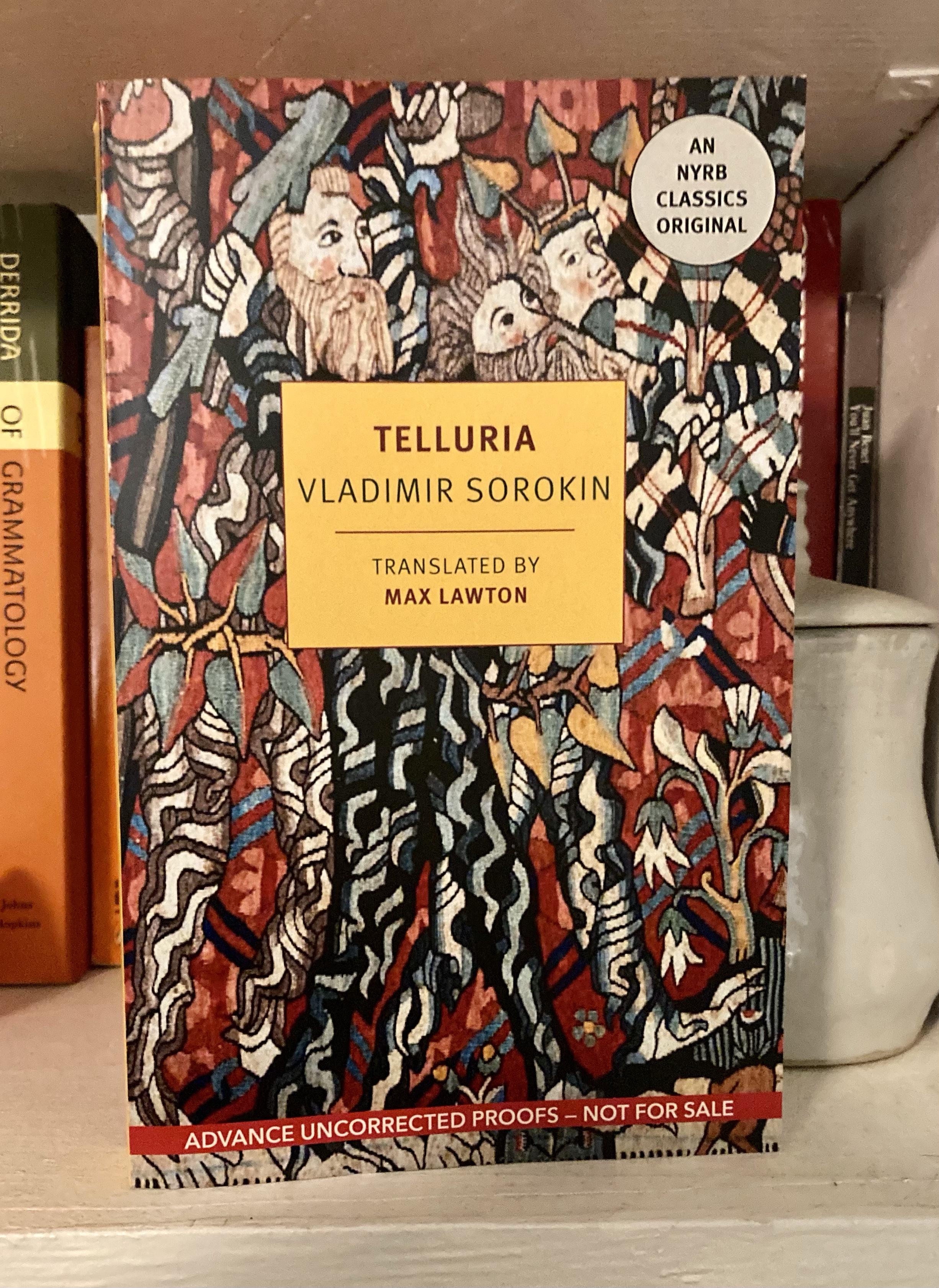

I’m really excited about Vladmir Sorokin’s postapocalyptic novel Telluria (translation by Max Lawton). I’m so excited that I’ve decided not to have anxiety and commit to a proper review by the time it comes out this summer.

Esther Allen’s translation of Antonio di Benedetto’s 1965 novel Zama is one of the best books I’ve read in the past five years, so I was very happy to get Allen’s translation of El silenciero — The Silentiary–a week or two ago. I was so happy that I added the book to a stack of books I was intending to read, rubbed my eyes really hard, let anxiety pulse through me, and read a little more of the Pessoa (which added a different layer of anxiety).

Writing about these anxieties has not purged them, but maybe I have a plan, or an outline here, a promise to myself (but not you, if you’re reading this, I promise you nothing, to be clear). Maybe I’ll dig in, set an early AM alarm to read an extra hour or so. Maybe I’ll even quit acquiring new books for awhile.

(Or not, no, I’ll just lie to myself some more.)

Moon in Alabama, 1963 by Lynn Chadwick (1914-2003)

Moon in Alabama, 1963 by Lynn Chadwick (1914-2003)