Previously on Blue Lard…

Previously on Blue Lard…

The following discussion of Vladimir Sorokin’s novel Blue Lard (in translation by Max Lawton) is intended for those who have read or are reading the book. It contains significant spoilers; to be very clear, I strongly recommend entering Blue Lard cold.

When I started this series of posts, I was rereading the print edition of Blue Lard after having read Max’s manuscript translation a few years ago. I have gotten so behind in this post series that I am now re-rereading. After having read the book essentially three times now, I find that it is far more precise and controlled than my initial impression–which I guess makes sense. Blue Lard is hypersurreal, shocking, deviant. But it’s also more balanced and nuanced than a first go-through might suggest, not just absurdist shit-throwing and jabberwocky, but an accomplished analysis of the emerging post-Soviet era.

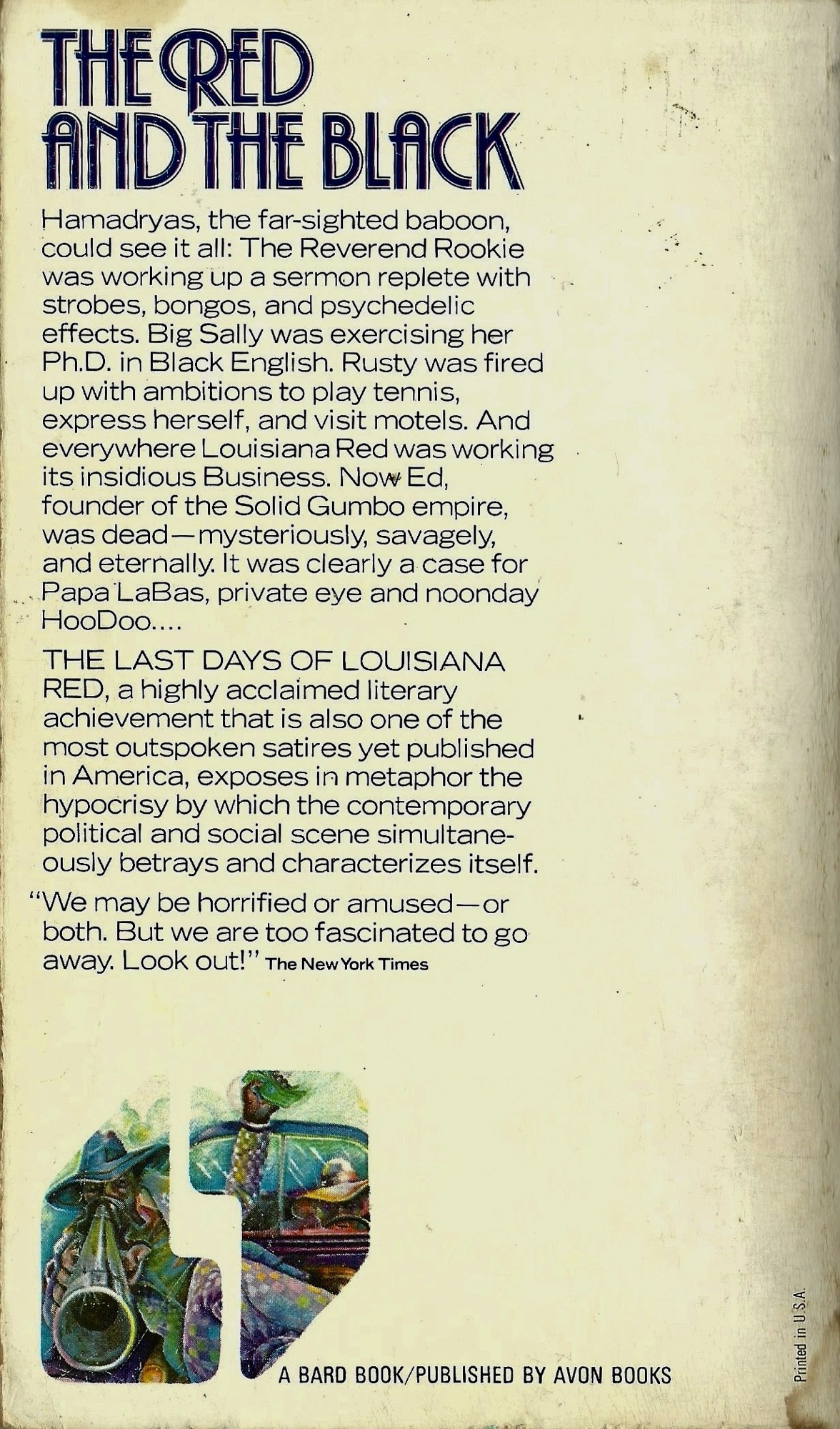

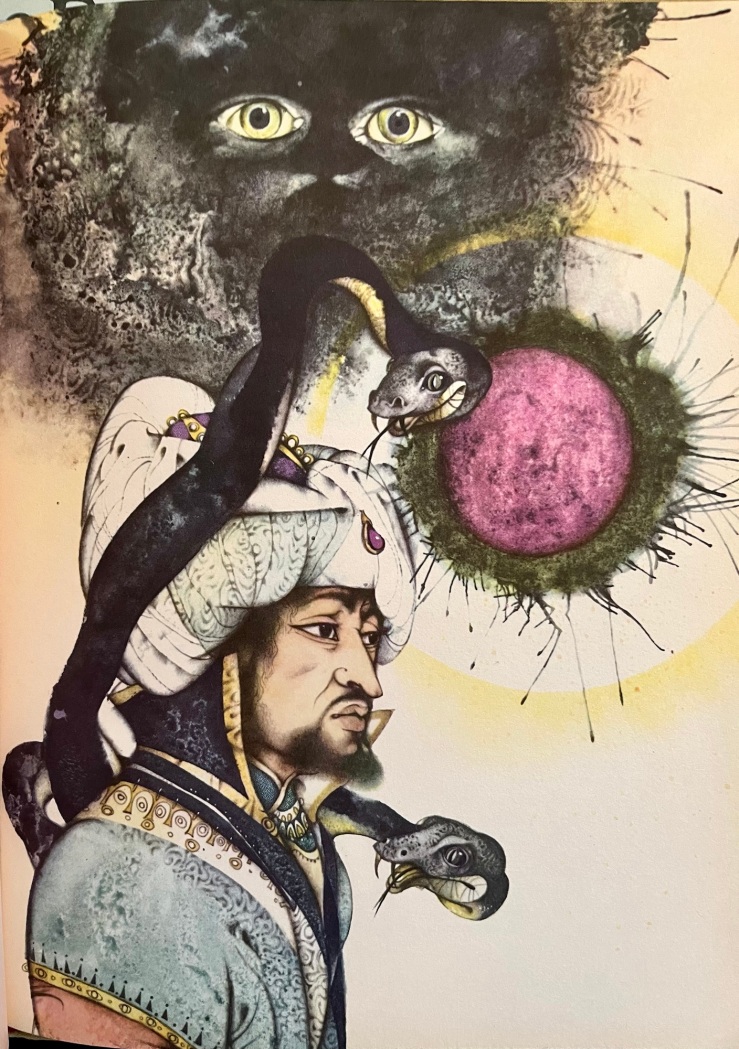

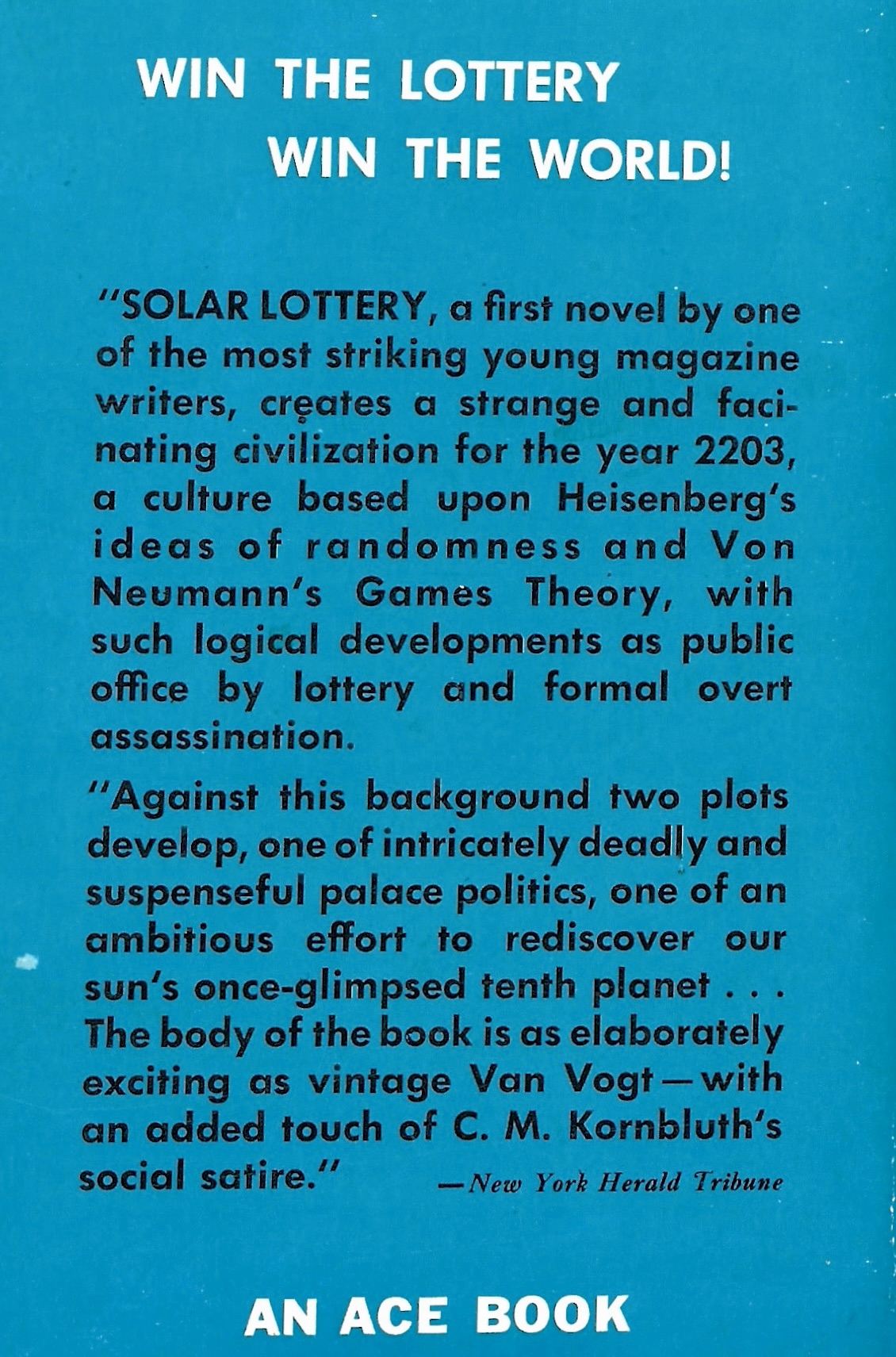

We left off our Blue Lard riffs with the pop art glamour and swagger of the Stalin family, drawn in bold but neat caricature. Stalin departs the dramatic inner circle/family circle on his way first to lieutenant Beria’s and then to his part-time lover Khrushchev’s, but as he’s on his way, “a fat woman dressed in rags hurl[s] herself toward the motorcade with a mad cry.” Stalin’s guards draw their weapons, but Our Boy is quicker: “‘Don’t shoot!’ Stalin ordered. ‘It’s Triple-A! Stop!'”

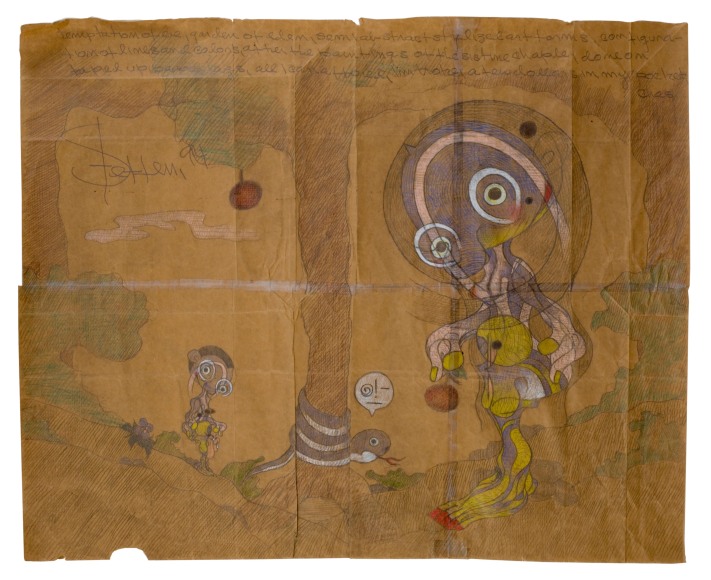

Triple-A is the poet Anna Akhmatova (who we first met via reincarnation as the kindaclone Akhmatova-2 back in the future). She’s fat gross and happy, pregnant with an aesthetic revelation of abjection:

Her wide, round face with its broken nose was flat and her small eyes shone with madness; tiny rotten teeth stuck out from beneath her formless wet lips; her unbelievably tattered rags adorned a squat body that widened freakishly as it went down; her dirty gray hair stuck out from beneath a ragged woolen kerchief; her bare feet were black with filth.AAA is one of Sorokin’s fouler concoctions, proclaiming proclamations like

“Did you know that Kharms feeds canaries with his worms?” Stalin asks AAA. (The absurdist poet and children’s author Daniil Kharms died in a Soviet prison in his mid-thirties. “Send him to the deepest north!” Sorokin’s Akhmatova advises Sorokin’s Stalin.) The conversation over Soviet writing continues: “‘I have an active dislike for Fadeyev’s Young Guard,'” declares Stalin.” A paragraph or two later, AAA licks the soles of his boots. I don’t know nearly enough about Soviet and Russian literature to figure out what or if Sorokin is satirizing here, but I think I know enough about the relationship of aesthetics and power to take a big hint.

Stalin’s motorcade drove up to Arkhangelskoye. Here, in a magnificent palace built during the reign of Catherine II, lived the count and previous member of the Politburo and of the Central Committee of the CPSU Nikita Aristarkhovich Khrushchev, who had been removed from his state duties by the October Plenum of the Central Committee.

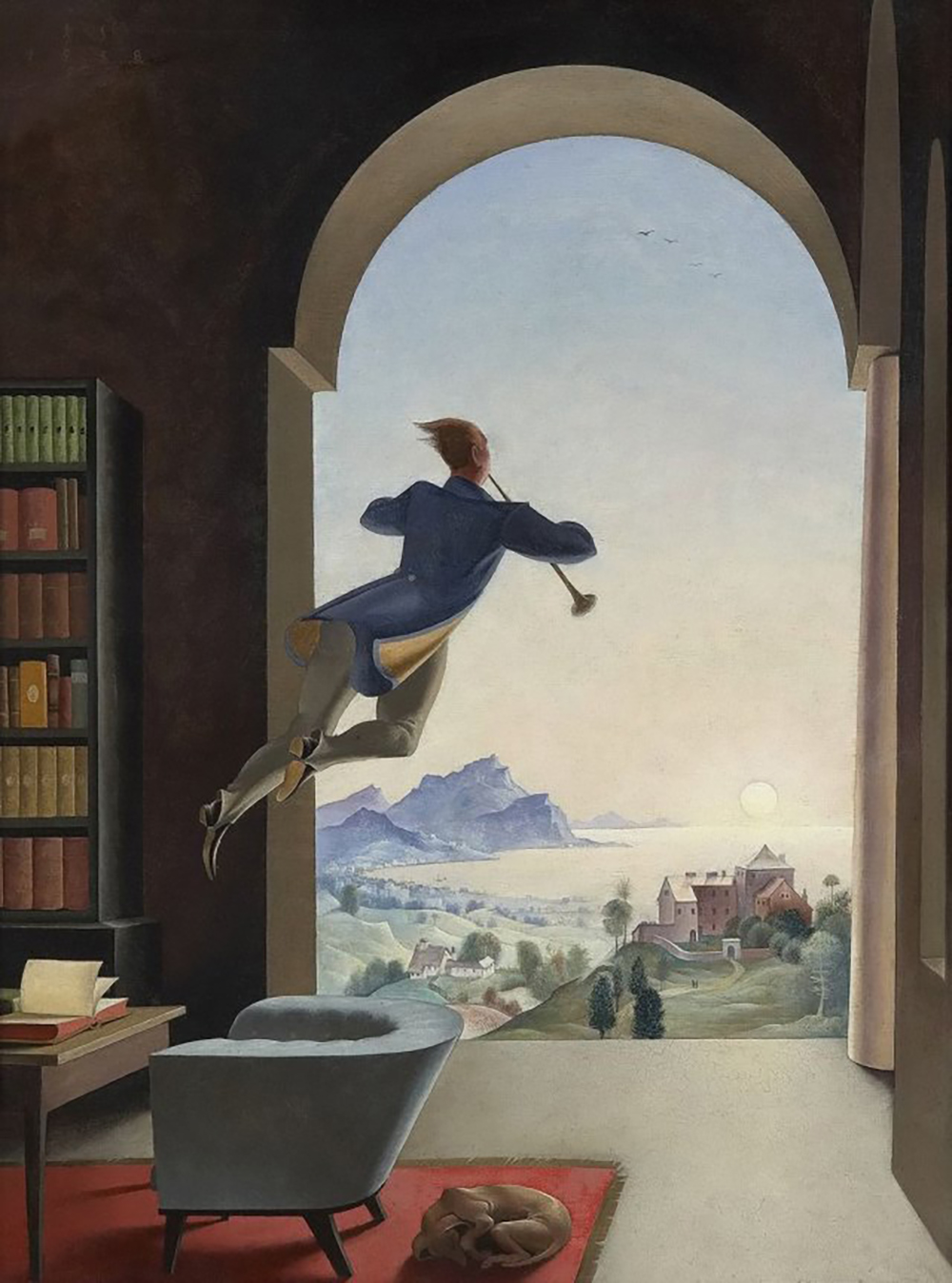

There is a famous infamous horny sensual sex scene between Stalin and Khrushchev coming up, one that has made Blue Lard famously infamous—but let’s set that aside for now. Sorokin’s Khrushchev’s patronymic Aristarkhovich doesn’t gel with our historical Khrushchev’s patronymic Sergeyevich. Is the “new” patronymic “Aristarkhovich” an allusion to the avant-garde painter Aristarkh Lentulov?

Sorokin’s presentation of Khrushchev as a hunchback may allude to the following incident, as reported in a 1973 The New York Times profile on the poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko: