☉ indicates a reread.

☆ indicates an outstanding read.

In some cases, I’ve self-plagiarized some descriptions and evaluations from my old tweets and blog posts.

I have not included books that I did not finish or abandoned.

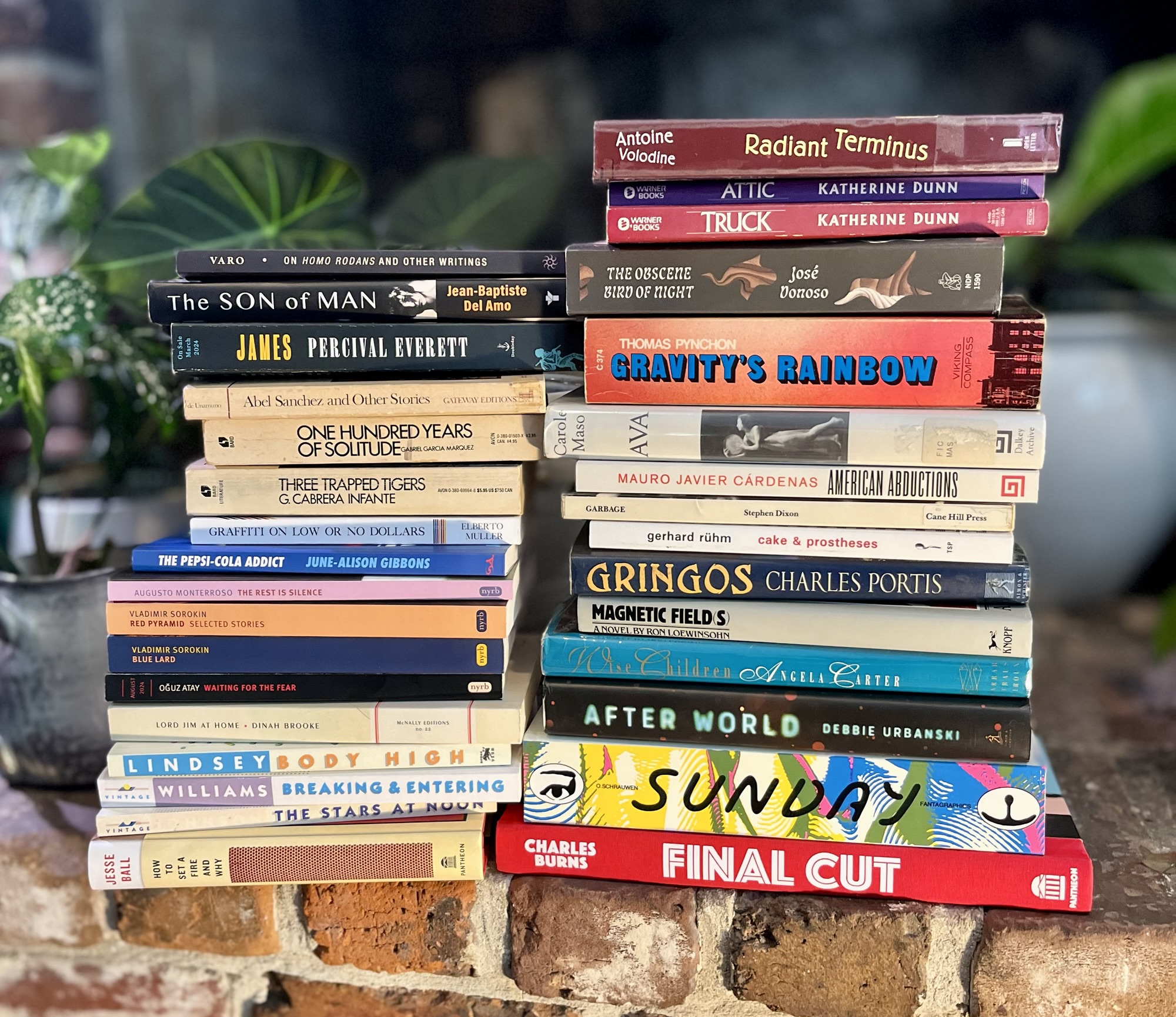

Cake & Prostheses, Gerhard Rühm; trans. Alexander Booth

Sexy, surreal, silly, and profound. Lovely little thought experiments and longer meditations into the weird.

Abel Sanchez and Other Stories, Miguel de Unamuno; trans. Anthony Kerrigan

Both sad and funny, Abel Sanchez, the 1917 novella that makes up the bulk of this volume, feels contemporary with Kafka and points towards the existentialist novels of Albert Camus

After World, Debbie Urbanski

Debbie Urbanski’s debut novel After World reimagines the end of humanity—or perhaps the beginning of a new digital existence. The narrator, [storyworker] ad39-393a-7fbc, reconstructs the life of Sen Anon, the last human archived in the Digital Human Archive Project, using sources like drones, diaries, and other materials. Drawing on tropes from dystopian and post-apocalyptic literature, this metatextual novel references authors like Octavia Butler and Margaret Atwood while nodding to works such as House of Leaves and Station Eleven. Urbanski’s spare, post-postmodern approach also reminded me of David Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress—good stuff.

Walking on Glass, Iain Banks

Walking on Glass weaves together three narrative threads: an art student’s infatuation, a paranoid-schizophrenic secret agent, and two ancient warriors trapped in a castle playing bizarre games. While the novel has some wonderful and funny moments, Banks’s debut The Wasp Factory is the stronger effort.

Red Pyramid, Vladimir Sorokin; trans. Max Lawton

If you’re interested in reading Sorokin but aren’t sure if you want to jump into the deep end with Blue Lard (or abject hell with Their Four Hearts), the collection Red Pyramid is a good starting place. In her blurb for the NYRB collection, Joy Williams describes Sorokin’s writing as “Extravagant, remarkable, politically and socially devastating, the tone and style without precedent, the parables merciless, the nightmares beyond outrance, the violence unparalleled.”

Ava, Carole Masso

The controlling intelligence of Carole Masso’s 1991 novel is the titular Ava, dying too young of cancer. Ava spools out in an elliptical assemblage of quips, quotes, observations, dream thoughts, and other lovely sad beautiful bits. Masso creates a feeling, not a story; or rather a story felt, intuited through fragmented language, experienced.

Dune, Frank Herbert☉

I have always remembered liking the first half of the first Dune novel and thinking that the book’s pacing, depth, and characterization falls apart in the second half. I thought the second of Villeneuve’s Dune films was so bad that I ended up listening to the audiobook to confirm if there was anything in the original material. The audit confirmed my suspicion that the first half of Dune is good—there’s a dinner scene that’s excellent—but the novel falls apart under its epic ambitions. Herbert is very good at writing about deceit, mind games, spycraft; he’s awful with action, legend, and myth.

Escape Velocity, Charles Portis

Charles Portis wrote five novels, all of which are excellent. He may have a perfect oeuvre. Escape Velocity collects some of his early journalism (he was on the Elvis beat for awhile, and then he covered the Civil Rights movement); there are also some short stories, a play, a few odds and ends. For completists only.

I Am Not Sidney Poitier, Percival Everett☆

A brilliant, picaresque satire that follows its absurdly named protagonist on a series of misadventures, washing the surreal in acid social commentary. A Candide for the cable teevee age.

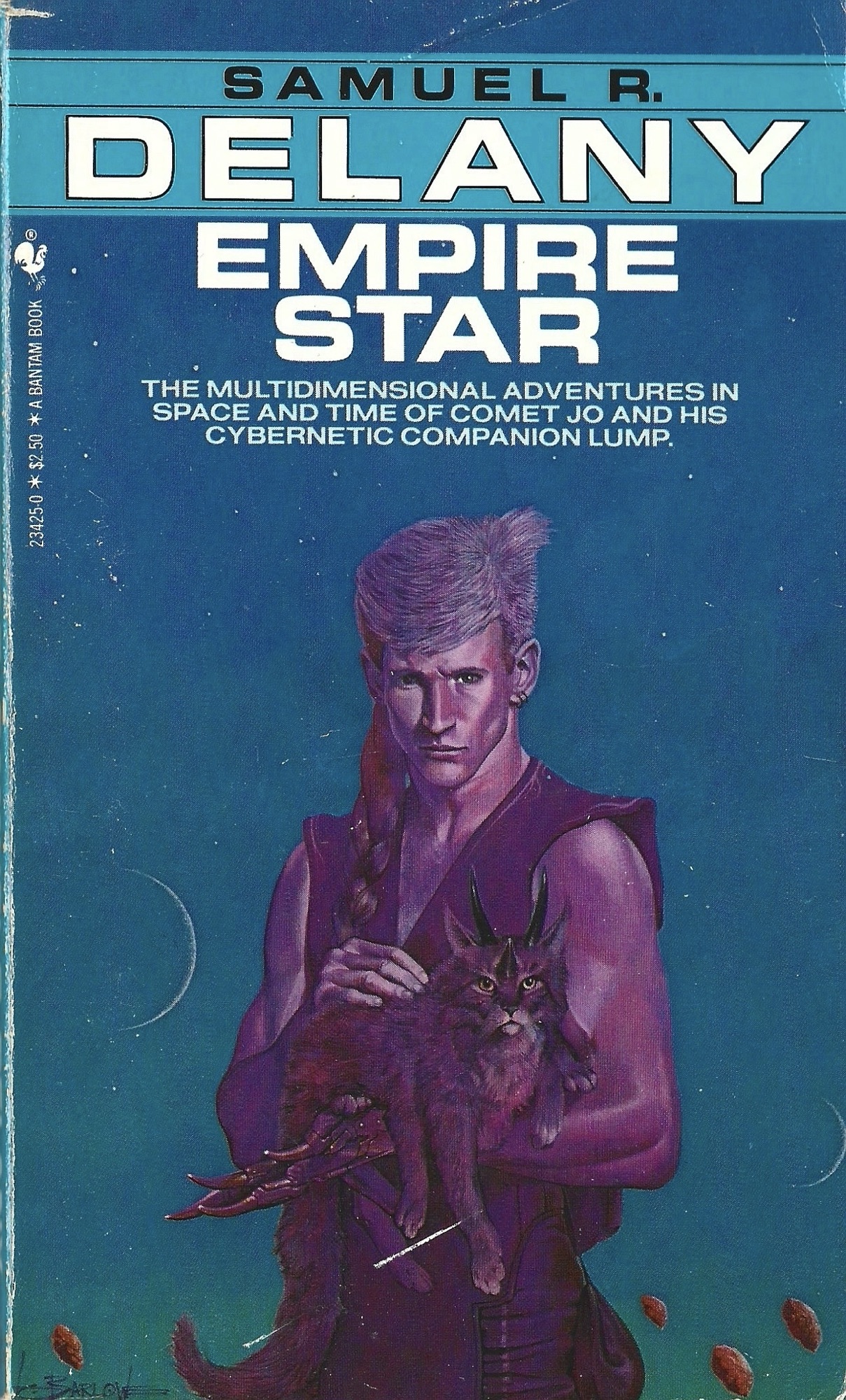

The Einstein Intersection, Samuel R. Delaney

Shambolic and mythic, Delaney’s novel retells the story of Orpheus in a narrative style that mirrors the musician’s dismemberment and fragmentation.

Blue Lard, Vladimir Sorokin; trans. Max Lawton☉☆

I ended up writing seven riffs on this novel this spring.

Telephone, Percival Everett

I don’t know which version I read, but it was sad.

How to Set a Fire and Why, Jesse Ball

I reviewed it here, writing, that the narrator “Lucia’s voice is the reason to read How to Start a Fire. It’s compelling and funny and persuasive and hurt. It seems authentic, and I admire the risk Ball has taken—it’s not easy to write a teenage girl who is also a maybe-genius-and-would-be-arsonist.”

The Pepsi-Cola Addict, June-Alison Gibbons☆

Loved this one. From my review: “The Pepsi-Cola Addict is a strange and unsettling tale of teen angst that stands on its own as a small burning testament of adolescent creativity unspoiled by any intrusive ‘adult’ editorial hand.”

James, Percival Everett☆

James will likely end up on everyone’s year-end “best of”; to be clear it is mine. Everett’s novel joins a shortlist of strong responses to Adventures of Huckleberry Finn that includes Leslie Fiedler’s Love and Death in the American Novel, Cormac McCarthy’s Suttree, and Robert Coover’s Huck Out West.

Gravity’s Rainbow, Thomas Pynchon☉☆

The key to reading Gravity’s Rainbow is to read it once and then read it immediately again and post a series of silly annotations on your literary blog and then to read it again a year or two later and then a few years after that to listen to it on audiobook while you pressure wash your house and the shed you built a few years ago (with the help of your father-in-law and brother-in-law) and then repaint the house’s shutters and then invent a few other chores so you finish the audiobook. And then write two more annotation blogs about it, eight years after the first series.

Progress, Max Lawton

The Abode, Max Lawton

I’m the sliverest slightest bit wary to include Max Lawton’s novels here, as the versions I’ve read are not necessarily the ones that will publish—but they are big, bold, ambitious, and strange, and they left an incisor-sharp impression upon me this year. Progress is a “maybe-this-is-the-end-of-the-world?” catalog of horrors; The Abode is a self-deconstructing catalog of catalogs, bildungsroman, a (self-)love story.

Demian, Herman Hesse; trans. Michael Roloff and Michael Lebeck

We’ve all had a good great bad evil friend.

Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Robert Louis Stevenson☉☆

I made my family listen to Ian Holm read RLS’s Jekyll and Hyde on a four-hire drive and learned that “Jekyll” is pronounced with a long e and not the accustomed schwa — it rhymes with “treacle” not “freckle.” The book is much better and weirder than I remembered.

One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez; trans. Gregory Rabassa☉☆

Much, much sadder than I’d remembered. I’d registered One Hundred Years of Solitude as rich and mythic, its robust humor tinged with melancholy spiked with sex and violence. That memory is only partially correct—García Márquez’s novel is darker and more pessimistic than my younger-reader-self could acknowledge.

On Homo rodans and Other Writings, Remedios Varo; trans. Margaret Carson☉

I enjoyed my discussion with Margaret Carson on her expanded translation of Remedios Varo’s fiction and letters.

The Son of Man, Jean-Baptiste Del Amo; trans. Frank Wynne

Enjoyed this one. From my review: “Del Amo gives us phenomena and response to that phenomena, but withholds the introspective logic of cause-and-effect or analysis that often dominates novels. Instead, he allows us to see what his characters see and to take from those sights our own interpretations.”

The Stars at Noon, Denis Johnson☉

A reread, but I honestly didn’t remember much about The Stars at Noon other than its premise and the fact that its narrator was an alcoholic journalist-cum-prostitute in Nicaragua. (That’s actually the premise.) It hadn’t made the same impression on me as other Johnson novels had when I went through a big Johnson jag in the late nineties and early 2000s, and I think that assessment was correct—it’s simply not as strong as Angels, Fiskadoro, or Jesus’ Son.

Radiant Terminus, Antoine Volodine, trans. Jeffrey Zuckerman☆

Excellent stuff; a highlight read of the year. From my review:

“Antoine Volodine’s novel Radiant Terminus is a 500-page post-apocalyptic, post-modernist, post-exotic epic that destabilizes notions of life and death itself. Radiant Terminus is somehow simultaneously fat and bare, vibrant and etiolated, cunning and naive. The prose, in Jeffrey Zuckerman’s English translation, shifts from lucid, plain syntax to poetical flights of invention. Volodine’s novel is likely unlike anything you’ve read before—unless you’ve read Volodine.”

Gringos, Charles Portis☉☆

Portis wrote five novels and all of them are perfect—but I think Gringos, his last, might be my favorite.

Lord Jim at Home, Dinah Brooke☆

Loved it. From my review:

“Lord Jim at Home is squalid and startling and nastily horrific. It is abject, lurid, violent, and dark. It is also sad, absurd, mythic, often very funny, and somehow very, very real for all its strangeness. The novels I would most liken Lord Jim at Home to, at least in terms of the aesthetic and emotional experience of reading it, are Ann Quin’s Berg, Anna Kavan’s Ice, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast novels, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, and James Joyce’s Portrait (as well as bits of Ulysses). (I have not read Conrad’s Lord Jim, which Brooke has taken as something of a precursor text for Lord Jim at Home.)”

American Abductions, Mauro Javier Cárdenas☆

Another favorite novel this year. From a riff back in October:

“If I were to tell you that Mauro Javier Cárdenas’s third novel is about Latin American families being separated by racist, government-mandated (and wholly fascist, really) mass deportations, you might think American Abductions is a dour, solemn read. And yes, Cárdenas conjures a horrifying dystopian surveillance in this novel, and yes, things are grim, but his labyrinthine layering of consciousnesses adds up to something more than just the novel’s horrific premise on its own. Like Bernhard, Krasznahorkai, and Sebald, Cárdenas uses the long sentence to great effect. Each chapter of American Abductions is a wieldy comma splice that terminates only when his chapter concludes—only each chapter sails into the next, or layers on it, really. It’s fugue-like, dreamlike, sometimes nightmarish. It’s also very funny. But most of all, it’s a fascinating exercise in consciousness and language—an attempt, perhaps, to borrow a phrase from one of its many characters, to make a grand ‘statement of missingnessness.'”

Attic, Katherine Dunn☆

Truck, Katherine Dunn

Katherine Dunn’s first novel Attic is seriously fucked up—like William Burroughs-Kathy Acker fucked up—an abject rant from a woman in prison in the mode of Ginsberg’s Howl. The narrator seems to be an autofictional version of Dunn herself, which is perhaps why Eric Rosenblum, in his 2022 New Yorker review described it as “largely a realist work in which Dunn emphasizes the trauma of her protagonist’s childhood.” Rosenblum uses the term realism two other times to describe Attic and refers to it at one point as a work of magical realism. If Attic is realism then so is Blood and Guts in High School. Her second novel Truck is equally weird, but it was maybe too much for me by the end.

Soldier of Mist, Gene Wolfe

Great premise, poor execution.

Final Cut, Charles Burns☆

In my review, I wrote that Final Cut served up “all the sinister dread and awful beauty that anyone following Burns’ career would expect, synthesized into his most lucid exploration of the inherent problems of artistic expression.”

Wise Children, Angela Carter

An enjoyable and maybe old-fashioned effort from Carter. I breezed through it, and remember it fondly.

Garbage, Stephen Dixon☆

I think Stephen Dixon’s novel Garbage was my favorite read of the year. I don’t know if it’s the best novel I read this year, but it was the most compelling—by which I mean it compelled me to keep reading, way too late some nights. From a thing I wrote a few months ago:

“I don’t know if Dixon’s Garbage is the best novel I’ve read so far this year, but it’s certainly the one that has most wrapped itself up in my brain pan, in my ear, throbbed a little behind my temple. The novel’s opening line sounds like an uninspired set up for a joke: ‘Two men come in and sit at the bar.’ Everything that unfolds after is a brutal punchline, reminiscent of the Book of Job or pretty much any of Kafka’s major works. These two men come into Shaney’s bar—this is, or at least seems to be, NYC in the gritty seventies—and try to shake him down to switch up garbage collection services. A man of principle, Shaney rejects their ‘offer,’ setting off an escalating nightmare, a world of shit, or, really, a world of garbage. I don’t think typing this description out does any justice to how engrossing and strange (and, strangely normal) Garbage is. Dixon’s control of Shaney’s voice is precise and so utterly real that the effect is frankly cinematic, even though there are no spectacular pyrotechnics going on; hell, at times Dixon’s Shaney gives us only the barest visual details to a scene, and yet the book still throbs with uncanny lifeforce. I could’ve kept reading and reading and reading this short novel; its final line serves as the real ecstatic punchline. Fantastic stuff.”

Graffiti on Low or No Dollars, Elberto Muller☆

A weirdo novel-in-riffs that I loved: bohemian hobo freight hopping, drug lore, art. Muller’s storytelling chops are excellent—he’s economical, dry, sometimes sour, and most of all a gifted imagist.

Galaxies, Barry N. Malzberg

Southern Comfort, Barry N. Malzberg (as “Gerold Watkins”)

A Satyr’s Romance, Barry N. Malzberg (as “Gerold Watkins”)

I really wanted to get into Galaxies, but I couldn’t. Malzberg’s faux-sci-fi metatextualist experiment carries his postmodernist anxiety of influence like a lance tilted against the would-be contemporaries who were more likely to get covered in The New York Times. His metamuscle is as strong as those folks, but you have to tell a story. I preferred the “erotic” novels I read that he wrote under the pseudonym Gerrold Watkins, 1969’s Southern Comfort and 1970’s A Satyr’s Romance.

The Singularity, Dino Buzzati; trans. Anne Milano Appel

From my review of The Singularity:

“Ultimately, The Singularity feels less like a novella than it does a short story stretched a bit too thin. Buzzati adroitly crafts an atmosphere of suspense and foreboding, but the characters are underdeveloped. Like a lot of pulp fiction, Buzzati’s book often reads as if it were written very quickly (and written expressly for money). Still, Buzzati’s intellect gives the book a philosophical heft, even if it sometimes comes through awkwardly in forced dialogue. Anne Milano Appel’s translation is smooth and nimble; it’s a page turner, for sure, and if it seems like I’ve been a bit rough on it in this paragraph in particular, I should be clear: I enjoyed The Singularity.”

Waiting for the Fear, Oğuz Atay; trans. Ralph Hubbell

A book of cramped, anxious stories. Atay, via Hubbell’s sticky translation, creates little worlds that seem a few reverberations off from reality. These are the kind of stories that one enjoys being allowed to leave, even if the protagonists are doomed to remain in the text (this is a compliment). Standouts include “Man in a White Overcoat,” “The Forgotten,” and “Letter to My Father.”

Making Pictures Is How I Talk to the World, Dmitry Samarov

Making Pictures spans four decades of Samarov’s career, showcasing his diverse styles—sketches, inks, oils, and more—through a thematically organized collection. His art, like his writing, emphasizes perspective over adornment, vividly depicting Chicago’s bars, coffee shops, and indie clubs.

Magnetic Field(s), Ron Loewinsohn☆

A hypnotic, fugue-like triptych exploring crime and art as overlapping intimacies. Through a burglar, a composer, and a novelist, it frames imagining another life as a taboo act of trespass.

Body High, Jon Lindsey

A breezy drug novel that’s funny, gross, and abject but tries to do too much too quickly. The narrator, a medical-experiment subject, dreams of writing pro-wrestling scripts, but spirals even further into mania when his underage aunt enters his life and stirs some disturbing desires. Body High is at its best when at its grimiest.

Sunday, Olivier Schrauwen☆

An achievement for slackers the world over. Sunday is a true graphic novel, by which I mean a real novel. Maybe I’ll get to a proper review of it; maybe The Comics Journal will ask me to come back to write reviews again. Anyway. Great stuff, a real achievement to those of us willing to drink a few beers before noon and fail to open the door when neighbors ring the bell.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, John le Carré☉☆

Perfect book.

Breaking and Entering, Joy Williams☆

Joy Williams’ fourth novel, 1988’s Breaking and Entering zigs when you expect it to zag. It ends up in a place no reader would expect, and I don’t mean that there’s some weird twist. It twists weirdly like life. The sentences are excellent, but so are the paragraphs. Breaking and Entering is very, very Florida, crammed with weirdos and tragedies, farcical, ironic, and thickly sauced in the laugh-cry flavor. I’m not sure exactly where it’s set, but I do know that I do know the general area, the barrier islands, skinny shining strips of weird between the Gulf and the Tampa Bay.

Hyperion, Dan Simmons

The Fall of Hyperion, Dan Simmons

I listened to Simmons’ mass-cult favorites as audiobooks—Hyperion was good; Fall was pretty terrible! But seriously, the first one is a nice postmodernist sci-fi take on Canterbury Tales.

Three Trapped Tigers, G. Cabrera Infante; trans. Donald Gardner and Suzanne Jill Levine with collaboration by Infante☆

Language! Language! Language! Bombastic, bullying, buzzing, braying, bristling— Infante’s dizzying mosaic of the fifties at night (and some hungover mornings) in Havana boxes you on your ear before kissing it, your ear, nipping the lobe even, showing off some neat tricks and other twisters of its fat vibrant tongue. A delight.

The Rest Is Silence, Augusto Monterroso; trans. Aaron Kerner

A quick clever slim novel that riffs on literary failure. A nugget from the so-called Latin Boom that surely (don’t call me Shirley!) influenced Roberto Bolaño.

The Obscene Bird of Night, José Donoso; trans. Hardie St. Martin, Leonard Mades, Megan McDowell☆

Heavy and gross, twisted and twisting, I loved Donoso’s The Obscene Bird of Night–reminded me of Goya’s Caprichos and William Faulkner and Anna Kavan soaked in Salò and Aleksei German’s adaptation of Hard to Be a God. About half way through I realized I needed to go back and put together some of the plot strands I’d missed; I think this novel is more coherent than its surreal and grotesque flourishes initially suggest.