A few years ago on this blog, I re-evaluated some of Frank Miller’s work, set against his fervent, blind support of the Bush wars. Today, I read a vitriolic rant by Miller, posted at his blog, where he offers the following clumsy thesis—

The “Occupy” movement, whether displaying itself on Wall Street or in the streets of Oakland (which has, with unspeakable cowardice, embraced it) is anything but an exercise of our blessed First Amendment. “Occupy” is nothing but a pack of louts, thieves, and rapists, an unruly mob, fed by Woodstock-era nostalgia and putrid false righteousness. These clowns can do nothing but harm America.

Miller offers no evidence about how or why the OWS protesters will “harm America,” nor does he support his claim that the protests are “anything but an exercise of our blessed First Amendment.” Honestly, I can’t even tell if Miller is being sarcastic when he writes “blessed” to describe the First Amendment, which clearly states that the citizens of this country have a right to assemble. Most Americans support the OWS movement, or at least the spirit of the movement, even if they do not agree with all of the tactics or, um, fashion sense and personal hygiene habits of the group. But Miller, furious reactionary that he is, does not bother once to consider a single idea put forth by OWS. He cannot see past the personal attire and fashion sense of some of the protesters, writing that the movement is nothing “more than an ugly fashion statement by a bunch of iPhone, iPad wielding spoiled brats who should stop getting in the way of working people and find jobs for themselves.” Those kids with their iPhones!

In a baffling move of obscure non-logic, Miller then connects OWS to his “enemies,” those nefarious (if nebulous) forces “al-Qaeda and Islamicism.” The piece ends with this disingenuous call to action—

In the name of decency, go home to your parents, you losers. Go back to your mommas’ basements and play with your Lords Of Warcraft. Or better yet, enlist for the real thing. Maybe our military could whip some of you into shape.

Miller of course never served in any branch of the armed forces. He also has never heard of/chooses to ignore clear evidence that veterans are part of this movement, including Scott Olsen, who was badly injured by police in Oakland.

Since Frank is so frank, let’s all be frank: Frank Miller is a tedious, ill-informed, rage-choked hack who hasn’t produced a great work in over two decades.

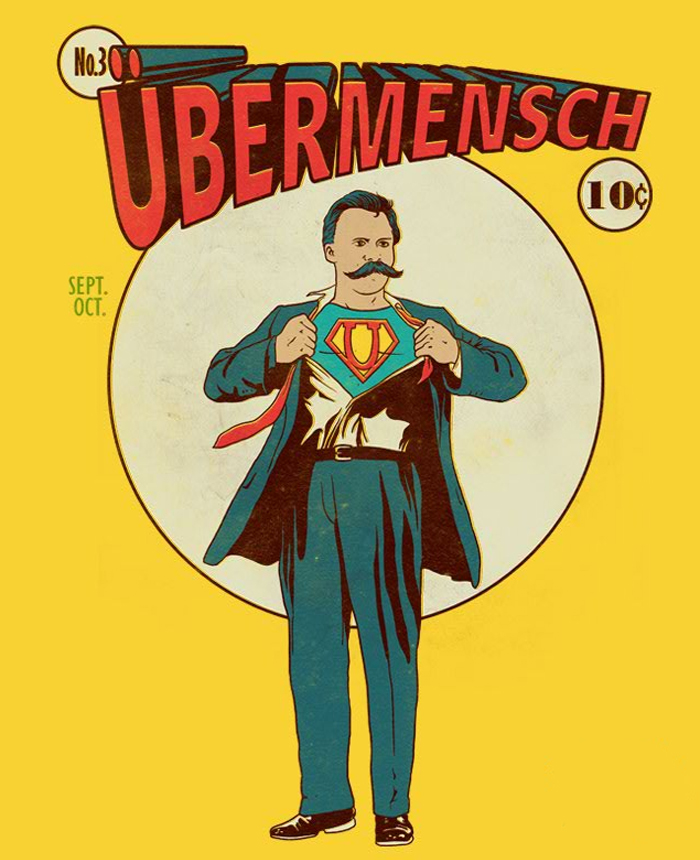

Even worse, he’s a fascist.

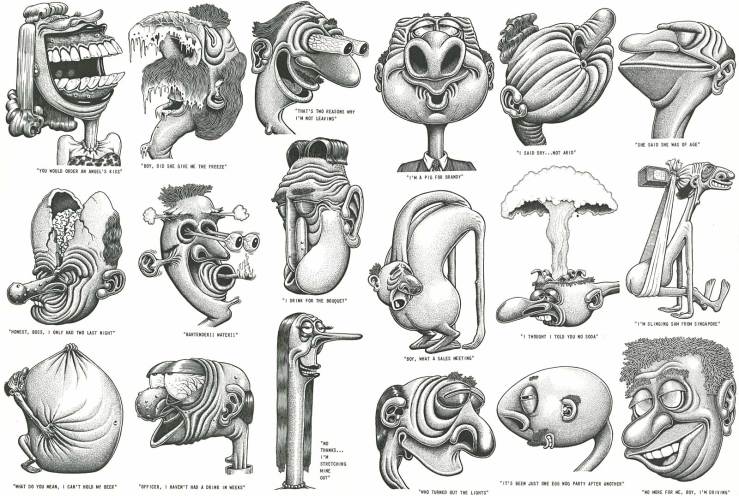

Miller’s early work in the 1980s repeatedly pointed toward the essential conflict of individual versus society; his heroes and anti-heroes constantly found themselves squaring off against corrupt totalitarian systems that sought to silence dissent and curtail civil liberties. As Miller’s career fumbled along, he increasingly endorsed the underlying fascistic elements present in his vigilante heroes, a fascism wed to an image of the hero as a man whose uncompromising ideals—and uncomplicated misunderstandings of a complex world—inevitably lead to brutal violence. See, for example, Miller’s most recent effort, Holy Terror, an extremely poorly received piece of anti-Muslim propaganda, reviled by comic book audiences not entirely because of its ideological content, but also because of its poor execution. (For a detailed and insightful take-down of Miller’s pulp trash, read Spencer Ackerman’s review in Wired).

Miller is a reactionary crank, a regressive thinker who is terrorized by the idea that the America “he knows” is no longer the homogeneous ideal that it once was. Of course, America was never an idealized homogeneous space, but that doesn’t matter. That’s what fantasy is for. And Miller is a professional fantasist. His derangement evinces not just in his reactionary vitriol toward the OWS protesters, but also in his apparent fear of the technology that these “iPhone, iPad wielding spoiled brats” use to disseminate their message.

Take note that never once in his screed does Miller attempt to paraphrase, analyze, refute, address, or otherwise actually engage that message. Presumably he can’t; he can’t hear it. Like one of the flat characters in his comics, perhaps Miller’s own interior monologue edges out all other voices, reinforcing his own paranoid delusions that “others” are lurking in the shadows, ready to take away the precious freedoms and ideals that only he can understand and value.

One is tempted to point out that Ezra Pound, G.B. Shaw, and Virginia Woolf, among other modernists, supported fascism, that Heidegger was a member of the Nazi party, and yet these artists and thinkers maintain a canonical place to this day in their respective fields. Will history be so kind to Miller? This is an earnest question. Certainly The Dark Knight Returns is a singular work in the superhero comics genre. But works like Holy Terror will do little to preserve the reputation of the man behind the Robocop sequels and The Spirit movie. Great art will survive the straining force of history, but I do not think that Miller is a great artist. He’s just a loud, angry cartoonist with ugly, unfounded, illogical opinions—and I think that that is what history will show.

Lots of

Lots of