Adam Novy’s debut novel The Avian Gospels is one of the best novels I’ve read this year, and one of the best contemporary novels I’ve read in ages. It’s a surreal dystopian magical romance set against the backdrop of political and cultural repression, violent rebellion, torture, family, and birds. Lots and lots of birds. (Read my review).

Adam Novy’s debut novel The Avian Gospels is one of the best novels I’ve read this year, and one of the best contemporary novels I’ve read in ages. It’s a surreal dystopian magical romance set against the backdrop of political and cultural repression, violent rebellion, torture, family, and birds. Lots and lots of birds. (Read my review).

Adam was kind enough to talk to me about his work over a month-long series of email exchanges; the interview presented below reveals much of his generous, creative energy.

Adam currently teaches writing at Scripps College, Pasadena City College, Long Beach City College and Orange Coast College.

The Avian Gospels is available now from Hobart.

Check out Adam’s website.

Biblioklept: I have a lot I want to ask you about what’s in your novel, but I have to start by asking about the physical book itself. The Avian Gospels is a lovely little two volume pocket-sized monograph—textured oxblood covers, gilded pages with line numbers, inset bookmarks. Visually, it recalls a Gideon bible, I guess, only not, I don’t know, chintzy. Where did the design idea come from?

Adam Novy: My editor at Hobart, Aaron Burch, had the idea of making the book look like a Bible. He’s an excellent designer and does a wonderful job with Hobart. Some boheemith press in New York City should really snap him up.

Biblioklept: How did the idea for The Avian Gospels come about? When did you start drafting the book? How long did it take to write?

AN: After 9/11, there was a moment where I felt like all Americans were on the same team. Now I wonder if we’ll ever feel that way again. Pardon me for living in the moment, but this country is just so completely fucked. This sensation of being American swiftly curdled into panic, but by then, the coordinates of my work had all been changed. I wanted to find a voice with room for both the historical and the intimate, which led me to a kind of first-person plural officialese. It ended up creating this echo-chamber effect where the personal and political identities of each character were different, and nobody could quite be who they were supposed to be, or wanted to be.

It took months of screwing around to figure this out, and most of it, of course, was accidental. The Lord of the Rings was on TV a lot at the time, and sometimes I thought I wanted to sound like Gandalf if Gandalf was full of shit and, like, a genocider who felt sorry for himself, but still was Gandalf, all mystical and officious, bossing everyone around. I understood the characters right away, except for Jane, who was always hard to deal with. She gets in arguments a lot and she’s usually right. I think I have hard time writing characters who are right. I myself am never right, so I had trouble relating to her. Of course, now she’s my second-favorite character in the book, after Mike.

I started the book in spring of 2002 and finished it in fall of 2005. In 2006, I found an agent and Hobart took the book in 2008. I went through five apartments, three different cities, three computers, one personal trainer and three therapists in that time. And nine adjunct faculty positions.

Biblioklept: It’s interesting that you mention the LOTR movies as a kind of ambient influence, because they were pretty ubiquitous in the last decade—and there’s so much of the last decade’s zeitgeist in your book: torture, despotism, political and cultural repression, the plight of a refugee class, the idea of “green zones,” etc. You foreground these themes by crafting Gospels as a kind of dystopian novel with elements of magical realism, but it’s also very much a novel about family, and even a love story. (By sheer coincidence I watched the restored edit of Metropolis in the same time frame that I was reading Gospels, and saw so many echoes there). How conscious were you of genre conventions? I’m curious because your book sometimes blends genre tropes, sometimes blurs them, and sometimes straight-up explodes them . . .

Biblioklept: It’s interesting that you mention the LOTR movies as a kind of ambient influence, because they were pretty ubiquitous in the last decade—and there’s so much of the last decade’s zeitgeist in your book: torture, despotism, political and cultural repression, the plight of a refugee class, the idea of “green zones,” etc. You foreground these themes by crafting Gospels as a kind of dystopian novel with elements of magical realism, but it’s also very much a novel about family, and even a love story. (By sheer coincidence I watched the restored edit of Metropolis in the same time frame that I was reading Gospels, and saw so many echoes there). How conscious were you of genre conventions? I’m curious because your book sometimes blends genre tropes, sometimes blurs them, and sometimes straight-up explodes them . . .

AN: The book is quite deliberately a mash-up. I think it’s normal in conversation to try out different ways of seeing things—a fussy way of saying this might be “experiment with different hermeneutics.” For example, one might reference the NBA, The Wire, Shakespeare and Dazed and Confused in a discussion about Obama. I wanted the book to enact this kind of embeddedness, this flailing for a context that makes sense, and I wanted the narrator to sound as though its vernacular was ornate and obsolete, like it trafficked in a pleasure that justified itself as satisfaction while remaining an inadequate moral lens. That’s why I write violence like I do: I want it to be horrifying and beautiful. Unfortunately, violence is cool. I’m not immune—I always watch Kill Bill and Scarface when they’re on cable. It’s disturbing. Everyone knows that torture doesn’t work as an intelligence-gathering method, but our country did it anyway because it simply couldn’t stop. It was a kind of jacking off, the only kind that certain political parties seem to approve of.

Whenever we write about power, we should always defend the powerless, even if they’re just as bad as those in power. I think I saw that in Cioran, and did you know Cioran was a Nazi sympathizer? I just read that Gertrude Stein was, too. I don’t know what kind of paradigm can reckon with this world.

Biblioklept: I had no idea about Stein or Cioran’s Nazi sympathies, but I guess many artists and writers and intellectuals were attracted to the power of fascism, particularly in the modernists’ day (I suppose Ezra Pound and GB Shaw stand out as easy examples, and Heidegger was a member of the Nazi party). Although in our own age, I suppose we also see intellectuals and writers support terrible causes—I think of Christopher Hitchens’s aggressive support of the Iraq War and Bush administration’s policies, for, example.

I don’t want to drop spoilers, but your novel traces an arc that shows how those who are powerless might, given power, recapitulate the aggressive violence that they themselves were once subjected to. In turn, you also reveal how characters who seemed to occupy a clear power position (I’m thinking of Mike here, specifically) are perhaps doomed as well to a life without agency. I found my sympathies shift dramatically throughout the novel. How important are sympathetic characters?

AN: Every writer, including me, wants the reader to cathect to their book with their whole heart. I want my readers to utterly and helplessly engrossed. But sympathy is a means to an end and not the end itself. Technically speaking, it’s just not that hard to accomplish. It’s a skill, like dribbling in basketball is a skill, but it’s not the whole game.

In The Avian Gospels, the character named Mike Giggs is seen in only one scenario—exerting power in the manner of his father—for the first two hundred pages, so he comes off like a jerk until he encounters someone who actually loves him: Chico the band leader. Suddenly, Mike discovers a love of life, a sensitivity and a feeling of camaraderie for his fellows. Not only is he is capable of compassion, he is governed by it. This leaves him ruined in certain ways, but allows him to discover who he can be, and makes him (hopefully) sympathetic.

Meanwhile, on the other end of the book, the character named Zvominir, who was whimperingly sweet for longer than Mike was mean, is meaner than Mike. Novels are fantasies of powerlessness and power—among the zillion other things they are—and I feel like we should at least be conscious of what’s happening to our minds as we are reading. How we deal with power is a serious moral question; counting how many times that we go awwww is not. We have cats on the internet for that. Still, Chad Harbach was probably right when he said that the books that get the best reception are simply “affable.” In desperate times, a nation of New York critic types are turning to . . . Mitt Romney? Or like, Cheever without the psychosexual guilt?

I don’t mean to single out Chad Harbach, whose work I haven’t read, except for his piece on Grantland about the Brewers, which I liked. But what he said is accurate. These days, people seem to feel that art should be uplifting, like art owes it to them, in a customer-service type-way. Have you been to Kinko’s, or excuse me, FedEx Office, lately? It is not a happy place. Novels used to to give the reader the truth in ways no other social narratives would. I’m pretty sure I’m not just being sentimental. There used to be a social lie which said the world was making progress and ascending, but this reversed like fifteen years ago and now we all feel doomed. We need books to tell us how we got here, not to lie about how meaningful our journeys are or however we say it these days. Of course our lives are meaningful, but such a narrow focus on making folks feel better is superficial and disempowering. Our emptiness and dread are trying to tell us something.

Biblioklept: I think you point toward a distinction between art and entertainment here. We want entertainment to comfort us, to ease our worries. In contrast, art challenges us with what we don’t want to see, or can’t see, or can’t see that we can’t see. And yeah, there’s a kind of “literature of comfort” out there, books that simply reconfirm the tropes and tricks and forms of “literary fiction” — so that, even if the protagonists suffer, that suffering is is part and parcel of some greater telos — and not just in terms of the plot, but also in the structure of the novel itself. (Lee Siegel called this camp “Nice Writing” a decade ago, pointing to its “violent affability,” its “deadly sweetness”).

At the risk of asking one of those questions an interviewer is never supposed to ask (but, hey, I really want to know the answer and I think our readers would too), what books move you as a reader?

AN: I think I’m moved by pretty standard stuff. The Portrait of a Lady. Charlotte’s Web. To My Twenties, by Kenneth Koch. On Seeing the Elgin Marbles, by Keats. Places to Look For Your Mind, by Lorrie Moore. Testimony of Pilot and Return to Return by Barry Hannah. Antony and Cleopatra. Stone Arabia, by Dana Spiotta, which is the best new book I’ve read in 2011. Chopin in Winter by Stuart Dybek. The last paragraph of CivilWarLand In Bad Decline. The scene in American Tabloid where Ward steals the pension fund books. The Widow Aphrodissia by Marguerite Yourcenar. There must be fifty different scenes in Buffy that make me cry, and five in Battlestar Galactica. Certain scenes in Lost. This is such a conventional list, I feel like I need to start a fight. FRIDAY NIGHT LIGHTS SUCKS AND YOU ARE ALL A BUNCH OF SAPS. I should also say I’m moved by spectacles of massive human folly. The image of Slim Pickens riding the bomb and waving his hat in Dr. Strangelove and the scene where Kramer and his intern throw the ball of oil out the window are somehow very moving to me.

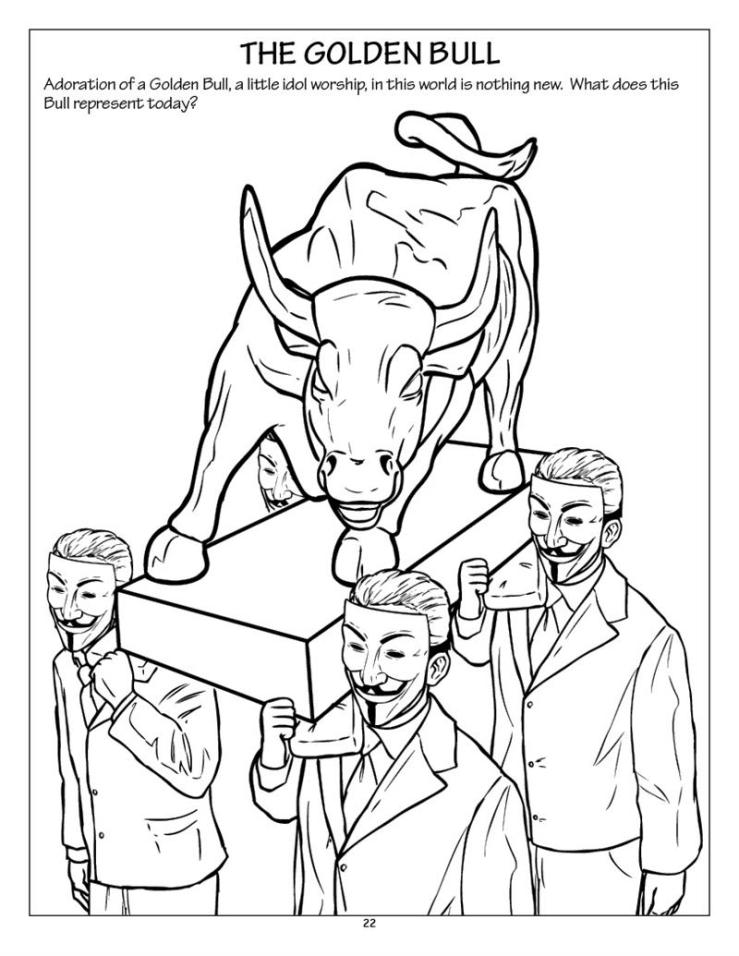

Biblioklept: I’d love to hear your thoughts on the Occupy Wall Street movement—The Avian Gospels taps into and explores this idea of civil unrest, of disenfranchised voices, of a paramilitary state coping with a populist uprising. You’ve indicated that your novel is in some ways a response to 9/11, but it also seems predictive of the fallout we’re seeing a decade after the fact.

AN: A massive, indescribable injustice was inflicted on our world by the likes of Goldman Sachs and we seem to have no recourse. Law enforcement could not possibly care less, and seeing how they cleared Zucotti Park, they seem jealous of the impunity of Wall Street. In his review of Ron Suskind’s book, Ezra Klein suggests that Washington just did not have the will to pass a stimulus that was big enough. Slavoj Žižek is right when he says this moment is a challenge to our imagination. I think that what happened at Penn State may be a better lens for the recession than Occupy Wall Street. A massive patriarchal network mobilized their resources to preserve an ongoing atrocity. No one will admit that they were wrong, especially the figurehead, Joe Paterno. The community just does not seem to give a shit. They keep telling out-of-towners we don’t get it and rioted in self-pity. I guess this is just how power acts.

Biblioklept: What’s next? What are you working on now?

AN: I’m writing a novel about the life and times of Medusa. It’s called The Gore and the Splatter.

Biblioklept: Have you ever stolen a book?

AN: I think the only book I ever stole was an anthology of world literature, which had a really coherent definition of French symbolist poetry. I can’t find this book now, so someone probably stole it from me. Serves me right.

Adam Novy’s debut novel The Avian Gospels is one of the best novels I’ve read this year, and one of the best contemporary novels I’ve read in ages. It’s a surreal dystopian magical romance set against the backdrop of political and cultural repression, violent rebellion, torture, family, and birds. Lots and lots of birds. (

Adam Novy’s debut novel The Avian Gospels is one of the best novels I’ve read this year, and one of the best contemporary novels I’ve read in ages. It’s a surreal dystopian magical romance set against the backdrop of political and cultural repression, violent rebellion, torture, family, and birds. Lots and lots of birds. ( Biblioklept: It’s interesting that you mention the LOTR movies as a kind of ambient influence, because they were pretty ubiquitous in the last decade—and there’s so much of the last decade’s zeitgeist in your book: torture, despotism, political and cultural repression, the plight of a refugee class, the idea of “green zones,” etc. You foreground these themes by crafting Gospels as a kind of dystopian novel with elements of magical realism, but it’s also very much a novel about family, and even a love story. (By sheer coincidence I watched the restored edit of Metropolis in the same time frame that I was reading Gospels, and saw so many echoes there). How conscious were you of genre conventions? I’m curious because your book sometimes blends genre tropes, sometimes blurs them, and sometimes straight-up explodes them . . .

Biblioklept: It’s interesting that you mention the LOTR movies as a kind of ambient influence, because they were pretty ubiquitous in the last decade—and there’s so much of the last decade’s zeitgeist in your book: torture, despotism, political and cultural repression, the plight of a refugee class, the idea of “green zones,” etc. You foreground these themes by crafting Gospels as a kind of dystopian novel with elements of magical realism, but it’s also very much a novel about family, and even a love story. (By sheer coincidence I watched the restored edit of Metropolis in the same time frame that I was reading Gospels, and saw so many echoes there). How conscious were you of genre conventions? I’m curious because your book sometimes blends genre tropes, sometimes blurs them, and sometimes straight-up explodes them . . .