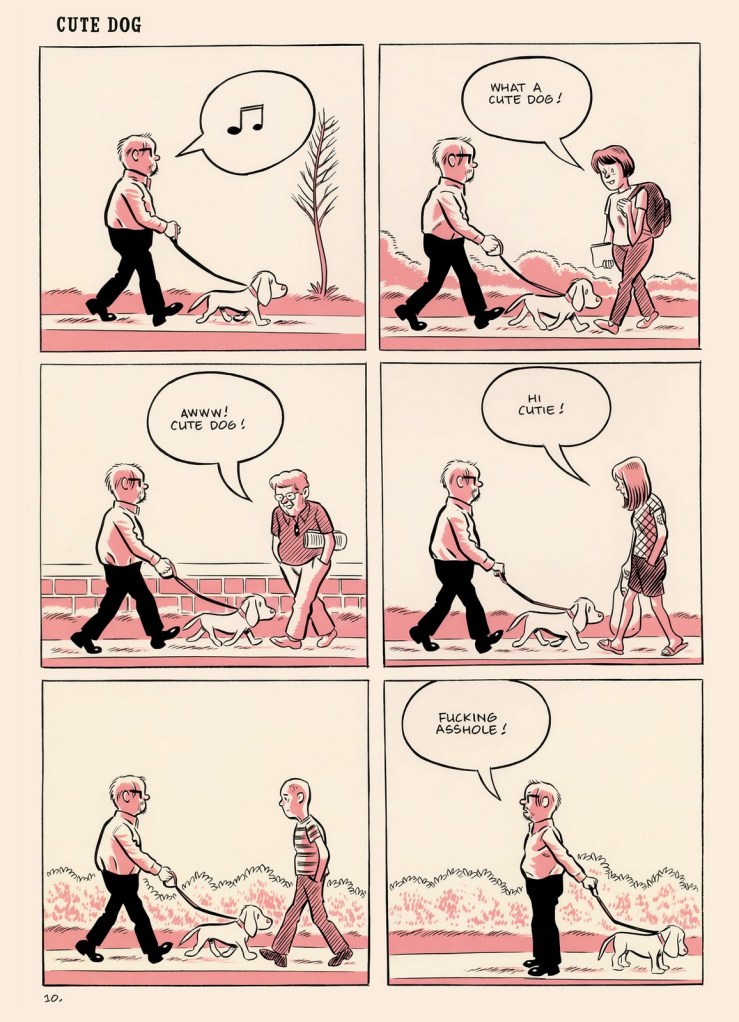

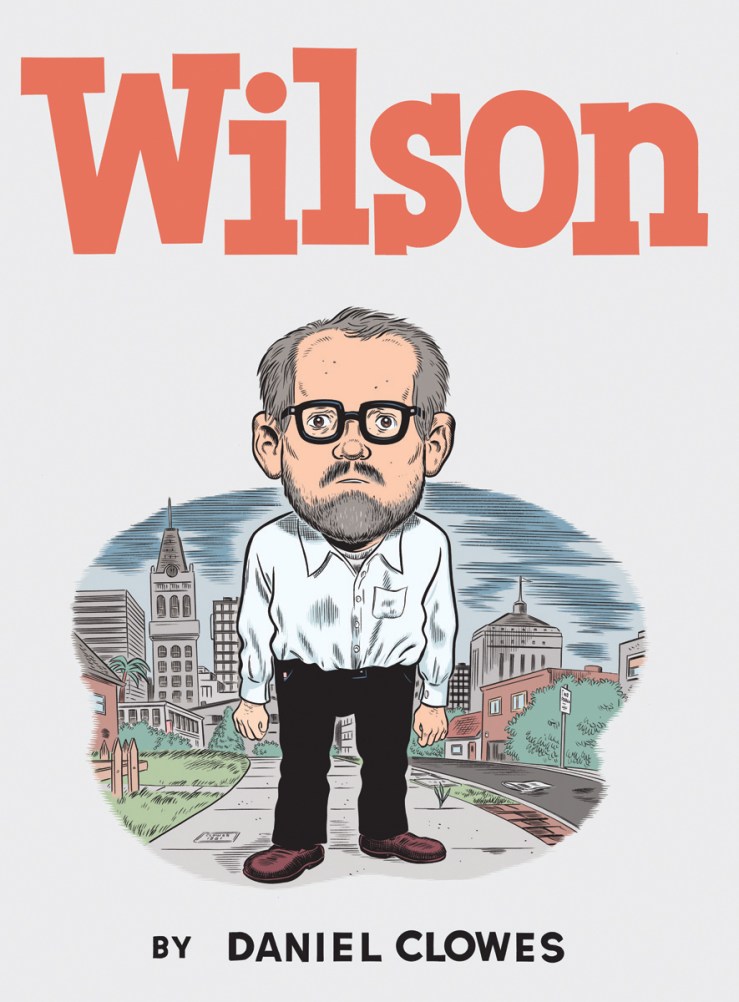

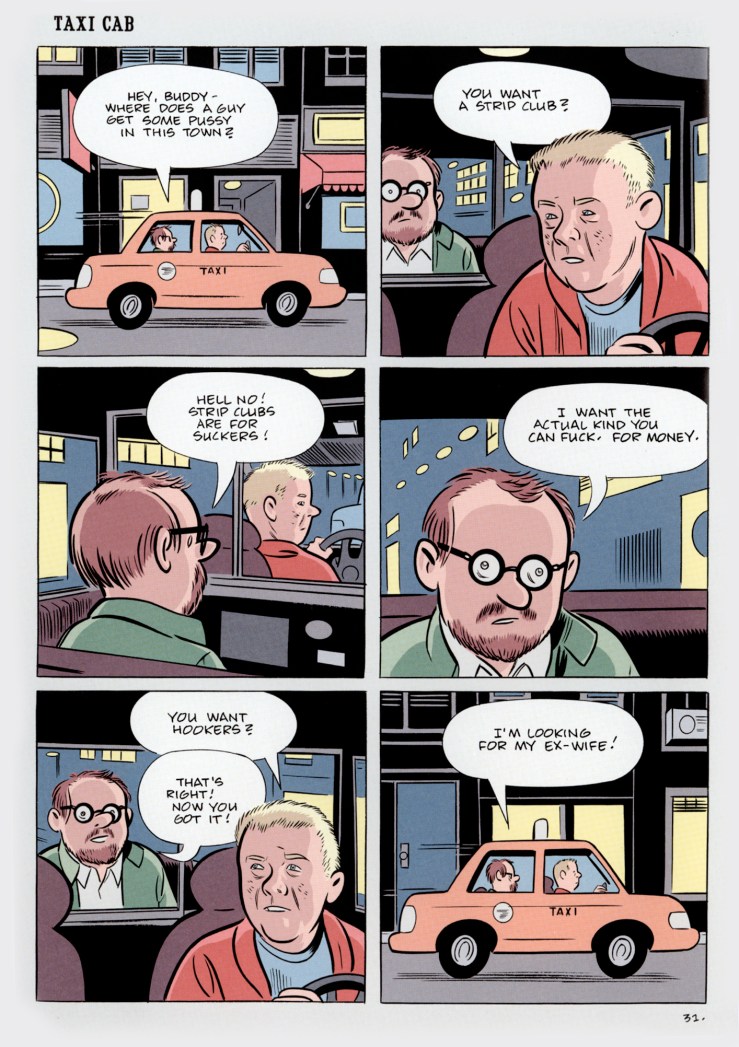

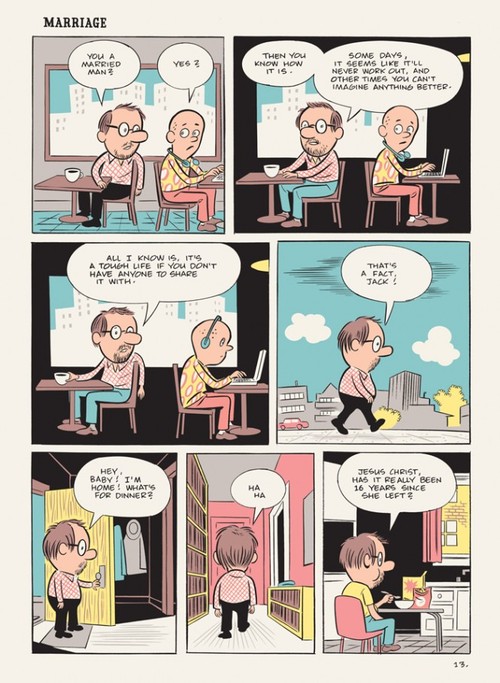

There’s an unexpected sweetness to Mister Wonderful, the latest work from Daniel Clowes (new in hardback from Pantheon). Sure, we’re still deep in Clowes territory here, with misanthropic protagonist Marshall offering up acerbic observations on wealthy yuppies, phony poseurs, and jerks on cell phones—all shot through a lens of self-loathing—but Mister Wonderful (subtitled A Love Story) is optimistic, a study in possibility that never tips over the sheer cliff of despair on the other side of romanticism. With its sense of balance, both emotional and narrative, Mister Wonderful is in some way the “good twin” to last year’s Wilson, a work that pointed to the illusory nature of growth and the futility of human connection.

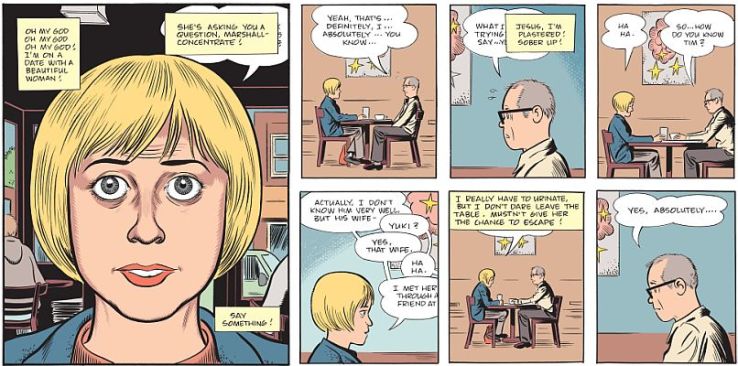

Where Wilson measured the life of its eponymous protagonist over decades (and in extreme hyperbole) as he sought to regain contact with his estranged family, Mister Wonderful covers just a few hours in the life of Marshall, a sad man set up on a blind date with nutty Natalie, a woman he immediately pegs as way out of his league. Marshall quickly romanticizes the possibility of a life with Natalie, struggling to keep his composure throughout their coffee and dinner date.

Natalie curtails the date to go to a party with old friends, but a surprise (violent) encounter allows Marshall a sliver of heroism—and a chance for more time with Natalie. They head to the party together, only to run into Natalie’s ex-boyfriend, giving Clowes plenty of oomph for a strong third act.

There’s a cinematic scope to Mister Wonderful. The book is 11″ x 6″, and Clowes makes excellent use of his Sunday’s comic page dimensions, exhibiting a level of detail and precision that imbue in Mister Wonderful an air of realism (one that contrasts the cartoony elements of evil twin Wilson). Clowes’s artistic powers are refined, balanced, and agile; he displays a command of color and shape that help define the strange emotional contours of Mister Wonderful, a book about second chances and those rare moments our interior lives might sync unexpectedly with the concrete possibilities life affords us.

Mister Wonderful is funny and balanced, but it’s not for everyone, including some longtime Clowes fans who might quibble with the book’s apparent slightness. Mister Wonderful clocks in at 80 pages, and while some readers may feel shortchanged, perhaps they are overlooking the scope of the work. Clowes is at the height of his powers here, deftly controlling a spare story about midlife tumult. There’s maturity and depth in this graphic novella. “Novella” isn’t the right term—Mister Wonderful is closer to a long short story, expertly told. Clowes still exhibits some of the sharp, mean edges that marked his earlier work, but the points are more finely honed, more subtle and precise. Some of the erratic weirdness we find in Clowes’s early stuff isn’t on display here, but this is more on account of Clowes’s stronger command of his medium’s formal elements. The bizarre, cynical spirit remains, however. Thankfully, Clowes makes no attempt to redeem his weirdos, nor does he push them into an unearned, false conclusion. Instead, Mr. Wonderful presents their problems and hang-ups and shortcomings as very real, even as it suggests a tint of unironic optimism. Recommended.