“Remember, remember the 5th of November…”

I was lucky enough to live in New Zealand for a few years as a kid, so I got to experience Guy Fawkes Day. We made effigies of Guy, then we burned them on a bonfire. There was a barbecue and fireworks. To my American ass, it seemed a mixture of the Fourth of July and Halloween—strange and marvelous.

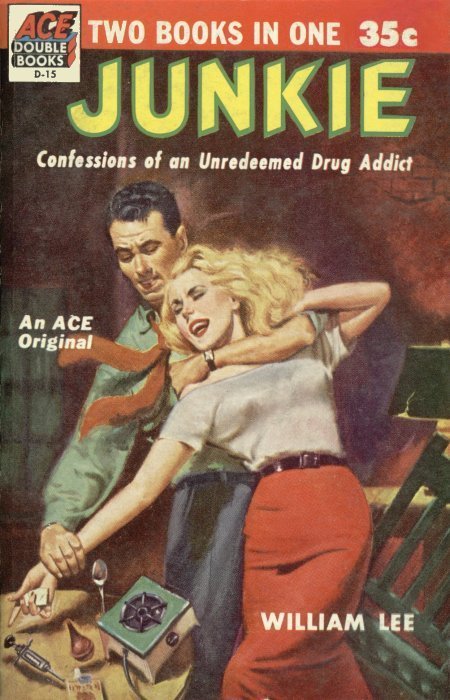

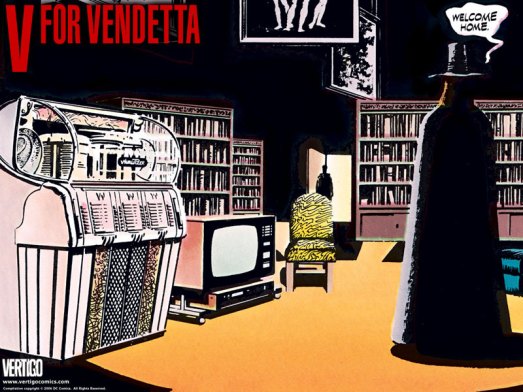

It was a few years after my last Guy Fawkes experience that I read Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta. V, an anarchist who wears a stylized Guy Fawkes mask, wages a vigilante war on a harsh authoritarian government. Along with Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, V was a first for me, something different from the comics I was reading at the time, stuff like Chris Claremont’s run on The Uncanny X-Men and other Marvel titles.

A film version of V for Vendetta was released in 2006; Alan Moore famously had his name removed from it. I enjoyed the film, although it certainly wasn’t as good or thought-provoking as Moore’s original story. And even though the film looked good, the passive experience of watching an action movie can’t measure up to David Lloyd’s original art work and that wonderful space between the panels of comics that engages the reader’s imagination.

This afternoon [see editorial note below] I finished the first graphic novel of Alan Moore’s run writing Swamp Thing, and I can’t wait until my library hold on the second graphic novel comes in. I had no idea Saga of the Swamp Thing would be as good as it was, nor as beautifully illustrated; it’s actually better than V for Vendetta or Moore’s other famed work, Watchmen (and none of these titles are even in the same league as Moore’s masterpiece, From Hell). Alan Moore and Steve Bissette’s run on the DC Comics series essentially led to DC’s creation of the edgier Vertigo imprint for their more “mature” titles, such as The Sandman. These titles helped to change the audiences of “comic books” and helped to make the graphic novel a new standard in the medium (no mean feat, considering the fanboyish culture of comic nerds, a culture that prizes rarity of print run over quality of storytelling).

One of the lessons in V for Vendetta is to illustrate what happens when we don’t allow for dissent, what happens when ideas are both prescribed and proscribed, and all dialogue is muted. Authoritarian governments consolidate their power from the silencing of ideas. A healthy society requires all sorts of opinions, even ones we don’t like. The smiling Americans in this photo aren’t burning effigies of would-be revolutionaries, they are burning something much more dangerous–books.

[Editorial note: So, I ran a version of this post on Nov. 5, 2006—it’s actually one of the first posts I ever did on the blog, which I began in Sept. 2006. Looking over it—which is to say editing it and making minor revisions (and grimacing frequently, but trying to keep those revisions minor, like moving commas)—I can see the growth and scope of the blog; especially I can see my own limited sense of what I wanted Biblioklept to be. The post also strikes me as excessively vague and preachy (especially that last paragraph, written after years of Bush Era Fatigue, which is kinda sorta still going on, I guess, Bush Era Fatigue, I mean, only I’d give it another name now). I wish I could remember more details of Guy Fawkes Day/Night, but I was young—9, 10, 11—and it seems vague. I still remember the history of Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot, although that’s probably more a result of paying attention in AP European History than anything else. This editorial note is way too long. I never finished Alan Moore’s run on Swamp Thing, but the second volume was good, as I recall].