We’re loving Jean-Christophe Valtat‘s new book Aurorarama, a steampunk-romance-high-adventure-academic satire-etc. set in the alternaworld of New Venice, an Arctic metropolis. Check out this post at MobyLives for a chance to win a copy of the book.

Tag: Books

“Are You Obscene?” — Play the New Interactive Howl Game

Play the new interactive game “Are You Obscene?” It may be a baldly mercantile device to promote the upcoming Allen Ginsberg biopic Howl, but it’s also pretty fun.

Here’s the trailer for Howl—

Cloud Atlas — David Mitchell

Friedrich Nietzsche famously wrote that “There are no facts, only interpretations.” David Mitchell takes this idea to heart in his 2004 novel Cloud Atlas, using six nested narratives to mull over Nietzschean matters of truth and perspective, the will to power, what it means to be a slave or a master, and the different methods by which one might narrativize one’s life. At its core, Cloud Atlas works to illustrate Nietzsche’s hypothesis of eternal recurrence, the idea that we live our lives again and again. To wit, each of the central characters in Cloud Atlas‘s six sections seems to be a reincarnation of a previous one. Mitchell arranges his narrative like a matryoshka doll, interrupting the first five stories with Scheherazade-style cliffhangers. Each narrative propels the book’s chronology forward a century or more until reaching a crescendo in a post-apocalyptic world, the only section that remains uninterrupted. Mitchell then resumes each narrative, working backward through time to his starting point in 1850, with The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing.

The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing features a naïve American’s tour of the South Pacific, focusing roughly on his trek from New Zealand to Hawaii. The journal’s style readily and purposefully recalls Herman Melville; indeed, Ewing himself professes to be a fan of Melville. Early in Ewing’s journal–which is to say, early in the novel Cloud Atlas–we are treated to (or subjected to) a somewhat lengthy description of the enslavement and slaughter of the pacifist Moriori tribes of the Chatham Islands at the hands of the Māori. Here, Mitchell introduces his novel’s dominant theme of slavery and civilization. Again and again in Cloud Atlas, we find groups of people preying upon other people, enslaving them and decimating their cultures. The Pacific Journal reiterates this theme when Ewing helps to rescue an enslaved Moriori who has escaped his slavers by stowing away; the episode also echoes the relationship between Ishmael and Queequeg, of course.

The next episode, Letters from Zedelghem, features a young bisexual composer named Frobisher; his narrative comprises letters he sends to his best-friend (and sometime lover) Rufus Sixsmith. Frobisher’s robust voice is one of the great achievements of Cloud Atlas; he finds music everywhere and in everything, and even though he repeatedly gets himself into terrible situations (which are always entirely his own fault) it’s hard not to feel for him. In debt and on the lam, he finds work as an amanuensis in Belgium, laboring under an aged, sometimes-despotic composer named Ayrs. Ayrs enlists Frobisher’s talents in creating a work named “Eternal Recurrence,” but ends up stealing most of his ideas. The Frobisher narrative is the only section to explicitly name Nietzsche and his ideas. Given the setting–Belgium, 1931, Europe precariously dangling before the precipice of another war–there’s a certain ambivalence toward Nietzsche perhaps, or at least a tacit acknowledgment that ideas like the Will to Power might be radically misapplied. Letters also most openly alludes to the structure of Cloud Atlas. In its second part–which is to say its conclusion, which is to say near the end of Cloud Atlas–Frobisher writes the following–

Spent the fortnight gone in the music room, reworking my year’s fragments into a “sextet for overlapping soloists”: piano, clarinet, ‘cello, flute, oboe, and violin, each in its own language of key, scale, and color. In the first set, each solo is interrupted by its successor: in the second, each interruption is recontinued, in order. Revolutionary or gimmicky?

Frobisher’s question perhaps reflects Mitchell’s own reticence over his complicated structure; in any case, it amounts to a post-modern wink. Frobisher’s narrative also initiates the book’s process of connecting the narratives, as each protagonist finds a copy of the earlier principal’s story. Frobisher finds Ewing’s Journal and devours it; in one of the book’s funnier moments, he scolds Ewing’s naïvety, comparing him to Captain Delano in Melville’s Benito Cereno. Frobisher’s criticism is apt. With its themes of slavery and mastery, truth and representation, and exterior and interior, there is probably no book that Cloud Atlas echoes as strongly as Benito Cereno.

Mitchell moves from a wonderful and witty approximation of the epistolary novel into a dull exercise in boilerplate fiction with the next narrative. Half-Lives: The First Luisa Rey Mystery follows the adventures of a plucky newspaper reporter in the 1970s as she tries to reveal a multinational corporation’s evil doings to the public. Aided by the report of a scientist named Rufus Sixsmith (yes, that Rufus Sixsmith), Luisa plunges into a world of intrigue and mystery and blah blah blah. Half-Lives intends to comment on airport novels, but Mitchell outdoes himself with the bad writing–it’s easily the weakest section of Cloud Atlas, and although it plays with the novel’s overarching themes it does little to enlarge or invigorate them. It does, however, introduce the comet-shaped birthmark that connects the heroes of these tales as they are born and reborn.

Mitchell seems more at home in the amplified voice that propels The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish. Set in and outside of London in the near future–that is to say, our near future–The Ghastly Ordeal is probably the funniest section of Cloud Atlas. Cavendish, the aging publisher of a small vanity press, finds success (and trouble) when one of his authors openly murders a critic. A dispute over royalties finds him hitting the road and fleeing for safety outside the urbane confines of London. Soon, he’s held prison in a home for the elderly somewhere in the barbaric north. Cavendish is scowling, imperious, overeducated, and arch; his racism and classism seem to belong to a different age and he’s prone to hyperbole (scratch that–he’s all hyperbole). Cavendish’s narrative is deeply reactionary: early in, he relates being mugged by a group of school girls, and the episode seems to come from A Clockwork Orange. How honest he is here, of course, is under suspicion, but that’s kinda sorta the whole point of Cloud Atlas. Cavendish’s narrative is the hardest to place stylistically–it doesn’t immediately resonate with any of the genre tropes that characterize the other section–but I suppose that there’s something of the post-Modernist (as opposed to postmodernist, of course) white-male-reactionary flavor to his Ordeal–hints of Saul Bellow, Updike, Roth perhaps? I’m not sure. The Ghastly Ordeal is the most contemporaneous episode of Cloud Atlas, so its tropes may be harder to spot.

The dystopian tropes of An Orison of Sonmi-451 are more readily apparent. Orison jumps centuries ahead, pointing to a future where an imperial Korean dominates what’s left of the non-burned Earth. Corporations have replaced government and consumerism has replaced religion. The rigid class structure that has developed relies on a slave class of fabricants–genetically modified clones–who perform dangerous jobs and manual labor. The narrative unfolds as an interview with Sonmi-451, a fabricant who “ascends,” positioning her in a level of unprecedented self-awareness that positions her to become the signal in a revolution to end slavery. There’s more to Orison than I can possibly unpack here, an observation that cuts both ways for Cloud Atlas. On one hand, Mitchell’s dystopia is repellent and enchanting, grimy and brightly lit, a world of fascinating extrapolations that mirror and satire contemporary society. On the other hand, Orison is overstuffed; its seams show the strains of containment. One gets the sense that Mitchell’s had to restrain an entire novel here, and the frequent need to dump exposition on his readers undercuts his otherwise nimble prose. (Alternately, the clunky exposition dumping might be a reference to Philip K. Dick). Mitchell is clearly comfortable working in the idiom of Orwell and Huxley (Sonmi explicitly references both writers, by the by), but the second half of Orison–the descending half, if you will–cannot reclaim the energy of its first part. Beyond Orison, a sense of contraction rules the second half of Cloud Atlas.

Perhaps the deflation in the novel’s second half results from its triumphant middle passage, Sloosha’s Crossin’ an’ Ev’rythin’ After. Dystopia moves to post-apocalypse, and maybe a thousand years after the time of Ewing, we are back in the Pacific, in the Hawaiian islands, where a man named Zachry spins one of the better adventure yarns I’ve heard in some time. Mitchell writes Sloosha’s Crossin’ in an invented argot that readily (and purposefully) recalls Russell Hoban’s post-apocalyptic masterpiece Riddley Walker. Like that book, Sloosha’s Crossin’ showcases an environment removed from the apocalypse–the narrative is more about how civilizations might reform after a fall. When a woman named Meronym from a “tribe” called the Prescients comes to stay with Zachry’s family, the stress between civilization and savagery comes to a head. The Prescients seem to be the last group of people on earth with any vestige of command over prelapsarian technology. Meronym (who bears a comet-shaped birthmark) does her best not to intervene in the day-to-day life of the family, but when the Kona, an aggressive tribe of slavers attack, she finds her self unable not to act. As the central, unbroken narrative of Cloud Atlas, Sloosha’s Crossin’ must both climax the novel as well as tie its disparate ends to its organizing themes. It doesn’t disappoint, both encapsulating, repeating, and commenting on the various slave-slaver narratives that run through the rest of the text. When the Kona attack Zachry’s Valleysmen, we see eternal recurrence–Māori slaughtering Moriori, Christian colonials ousting aboriginals, corporations using their fabricants for slave labor. A dialogue between Zachry and Meronym (delivered in Zachry’s argot, of course) spells out the novel’s concerns. Zachry asks Meronym if it’s “better to be savage’n to be Civ’lized?” She replies–

What’s the naked meanin’ b’hind them two words?

Savages ain’t got no laws, I said, but Civ’lizeds got laws.

Deeper’n that it’s this. The savage sat’fies his needs now. He’s hungry, he’ll eat. He’s angry, he’ll knuckly. He’s swellin’, he’ll shoot up a woman. His master is his will, an if his will say soes “Kill” he’ll kill. Like fangy animals.

Yay, that was the Kona.

Now the Civ’lized got the same needs too, but he sees further. He’ll eat half his food now, yay, but plant half so he won’t go hungry ‘morrow. He’s angry, he’ll stop’n’ think why so he won’t get angry next time. He’s swellin’, well, he’s got sisses an’ daughters what need respectin’ so he’ll respect his bros’ sisses and daughters. his will is his slave, an’ if his will say soes, “Don’t!” he won’t, nay.

What we see here is, I believe, a subtle reading of Nietzsche’s famous, infamous, and not-so-well understood concept of the will to power. Meronym’s solution to save endangered humanity is not blind adherence to conventional morality but rather an individual’s ability to overcome his or her animal instincts to thrive. The Übermensch enslaves his own will, his id, and preserves his ego.

As Sloosha’s Crossin’ concludes and Cloud Atlas moves outward and back into the past, there’s a twin sense of deflation and redemption. Orision does not have the room it needs to breathe; although Sonmi’s inevitable martyrdom follows a narrative logic that Sloosha’s Crossin’ more than justifies, it feels undercooked. The second half of the Cavendish narrative is more fulfilling. No spoilers. Mitchell manages to shoehorn a strange missive by a physicist into the second half of Luisa Rey; it’s only a page and a half, it doesn’t really belong there, and it’s the most interesting thing about the whole narrative. Like Frobisher’s description of his sextet, it functions as one description of the book. Luisa gets to hear that sextet, by the way; she special orders one of only fifty pressings. Frobisher’s narrative I’ve remarked upon at some length, so I will leave it alone by saying that it’s one of the finer points of Cloud Atlas and noting that it ends with a specific invocation of Nietzsche’s idea of eternal recurrence. The Journal of Adam Ewing is also very satisfying; in many ways it has to be, for it is the beginning and the end and the second end (and thus new beginning) of the novel. Ewing’s experiences–which, to leap right through the chain of protagonists, must also be Meronym’s experiences–lead him to reject the common morality of his time. As the novel concludes, he elects to return to the United States as a committed abolitionist, his stated mission in life to fight slavery in all its forms.

Cloud Atlas is a postmodern novel through and through. It riffs on genre and style with a keen awareness of textuality, an overt reliance on intertextuality, and a formally experimental schema that, as one of its principals puts it, might be “Revolutionary or gimmicky.” It lovingly pairs the high with the low, the philosophical with the vulgar, the musical with the mud, and its best moments do so seamlessly and gracefully. It’s a very good read–a fun read–and readers daunted by its structure need not be: Mitchell has created a book that they in many ways probably already know–they just don’t know that they know it like this. Highly recommended.

The Strange and Disorienting World of Authors’ Personal Libraries

Craig Fehrman’s new article “Lost Libraries” (at The Boston Globe) provides a fascinating overview of how author libraries — that is, the books, usually heavily annotated, that authors own — find their way into archives, and why those archives matter. Fehrman begins by detailing the strange case of recently-deceased novelist David Markson, whose personal library was kinda sorta reassembled by fans after a reader named Annecy Liddell bought Markson’s (cleverly-annotated) copy of Don DeLillo’s White Noise–

The news of Liddell’s discovery quickly spread through Facebook and Twitter’s literary districts, and Markson’s fans realized that his personal library, about 2,500 books in all, had been sold off and was now anonymously scattered throughout The Strand, the vast Manhattan bookstore where Liddell had bought her book. And that’s when something remarkable happened: Markson’s fans began trying to reassemble his books. They used the Internet to coordinate trips to The Strand, to compile a list of their purchases, to swap scanned images of his notes, and to share tips. (The easiest way to spot a Markson book, they found, was to look for the high-quality hardcovers.) Markson’s fans told stories about watching strangers buy his books without understanding their origin, even after Strand clerks pointed out Markson’s signature. They also started asking questions, each one a variation on this: How could the books of one of this generation’s most interesting novelists end up on a bookstore’s dollar clearance carts?

Fehrman g0es on to point out that–

David Markson can now take his place in a long and distinguished line of writers whose personal libraries were quickly, casually broken down. Herman Melville’s books? One bookstore bought an assortment for $120, then scrapped the theological titles for paper. Stephen Crane’s? His widow died a brothel madam, and her estate (and his books) were auctioned off on the steps of a Florida courthouse. Ernest Hemingway’s? To this day, all 9,000 titles remain trapped in his Cuban villa.

Why does this matter? As Fehrman notes, “authors’ libraries serve as a kind of intellectual biography.” And while universities do their best to archive these materials, as Fehrman’s article reveals, much of what gets saved is left to chance. For instance, how did David Foster Wallace’s personal library get to the Harry Ransom Archive?

When Wallace’s widow and his literary agent, Bonnie Nadell, sorted through his library, they sent only the books he had annotated to the Ransom Center. The others, more than 30 boxes’ worth, they donated to charity. There was no chance to make a list, Nadell says, because another professor needed to move into Wallace’s office. “We were just speed skimming for markings of any kind.”

Michael Greenberg on Roberto Bolaño

At The New York Times, Michael Greenberg tries to unpack the recent explosion of Roberto Bolaño books now available to English-reading audiences, including Antwerp, The Insufferable Gaucho, and The Return. From Greenberg’s review–

The Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño has to be one of the most improbable international literary celebrities since William Burroughs and Henry Miller, two writers whose work Bolaño’s occasionally resembles. His subjects are sex, poetry, death, solitude, violent crime and the desperate glimmers of transcendence that sometimes attend them. The prose is dark, intimate and sneakily touching. His lens is largely (though not literally) autobiographical, and seems narrowly focused at first. There are no sweeping historical gestures in Bolaño. Yet he has given us a subtle portrait of Latin America during the last quarter of the 20th century — a period of death squads, exile, “disappeared” citizens and state-sponsored terror. The nightmarish sense of human life being as discardable as clay permeates his writing.

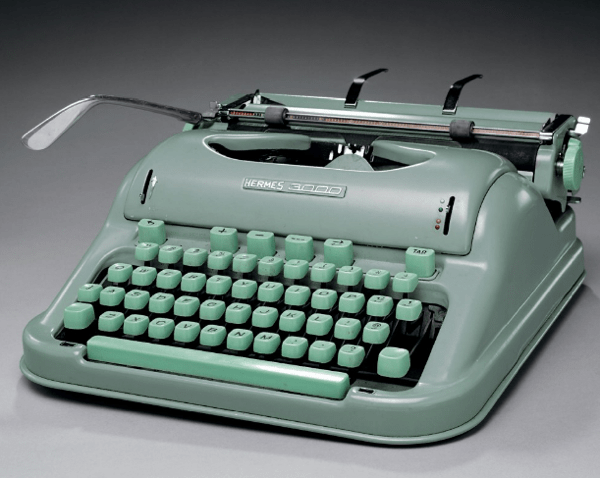

Famous Authors’ Typewriters

Odds and Ends

At A Piece of Monologue, Rhys Tranter reviews Simon Critchley’s “philosophical antidote to the self-help manual,” How to Stop Living and Start Worrying. Read our review of Critchley’s The Book of Dead Philosophers here.

MobyLives expands Flavorwire’s post on author photo clichés to include Melville House authors.

Here’s an author photo we love: Harold Bloom wearing big headphones and looking kinda skeptical and very green (the image is by Paul Festa from his film Apparition of the Eternal Church)–

If you still haven’t done your Juggalo Studies homework for this week, read Camille Dodero’s inspired report from this year’s The Gathering (at The Village Voice). And then watch “Miracles” again, because, hey, it only gets better. It still shocks the eyelids.

We love this tumblr (or is it tumblog?)–Anatomy–even if it looks like they aren’t doing much these days. C’mon guys. We need more gifs like this–

Finally, check out Stanford Kay’s series of paintings of books and bookshelves, “Gutenberg Variations.” Like abstract expressionism, only good (via) —

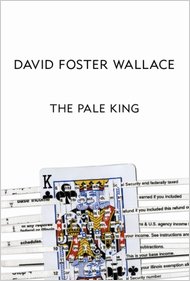

David Foster Wallace’s Posthumous Novel The Pale King Gets A Cover and Release Date

The New York Times reports that David Foster Wallace’s posthumous, unfinished novel The Pale King has the release date of April 15th, 2011–Tax Day–a fitting date, considering that the book is about an IRS tax return processing center. Little, Brown will publish the book. Here’s the cover–

David Foster Wallace Archive Opens to the Public

The David Foster Wallace Archive at the Henry Ransom Center (UTA) is now open to the public. The center will run a live webcast tonight at 8:00pm EST to celebrate the opening. In addition to his own materials, the collection holds over 300 of Wallace’s books–the majority heavily annotated.

The David Foster Wallace Archive at the Henry Ransom Center (UTA) is now open to the public. The center will run a live webcast tonight at 8:00pm EST to celebrate the opening. In addition to his own materials, the collection holds over 300 of Wallace’s books–the majority heavily annotated.

W.G. Sebald: Image, Archive, Modernity — J.J. Long

In W.G. Sebald: Image, Archive, Modernity, J.J. Long posits that the work of the late German author W.G. Sebald is best understood as the struggle for autonomous subjectivity in a world conditioned by the power structures of modernity. If the term “power structures” wasn’t a big enough tip-off, yes, Long’s analysis of Sebald is largely Foucauldian, and although he cites Foucault more than any other theorist (Freud is a distant second), the book is not a dogged attempt to make Sebald’s prose stick to Foucault’s theories. Rather, Long uses Foucault’s techniques to better understand Sebald’s works. As such, Long examines the ways that modernity affects power on the human body in Sebald’s work, tracing his protagonists’ encounters with modern institutions that exert power via archive and image.

In W.G. Sebald: Image, Archive, Modernity, J.J. Long posits that the work of the late German author W.G. Sebald is best understood as the struggle for autonomous subjectivity in a world conditioned by the power structures of modernity. If the term “power structures” wasn’t a big enough tip-off, yes, Long’s analysis of Sebald is largely Foucauldian, and although he cites Foucault more than any other theorist (Freud is a distant second), the book is not a dogged attempt to make Sebald’s prose stick to Foucault’s theories. Rather, Long uses Foucault’s techniques to better understand Sebald’s works. As such, Long examines the ways that modernity affects power on the human body in Sebald’s work, tracing his protagonists’ encounters with modern institutions that exert power via archive and image.

From the outset, Long distinguishes his book-length study on Sebald from the tradition of so-called Holocaust studies, as well as some of the other foci that dominate analyses of Sebald — “trauma and memory, melancholy, photography, travel and flânerie, intertextuality and Heimat.” Long claims that these are simply “epiphenomena” of the “problem of modernity” that dominates Sebald’s work, and goes on to scrutinize Sebald’s novels like The Emigrants, Austerlitz, and The Rings of Saturn by focusing instead on the various ways that modern institutions proscribe power on the subject’s body. Long writes–

Sebald is interested in the ways in which subjectivity in modernity is formed by archival and representational systems through which various forms of disciplinary power are exercised. He is also concerned with the scope that might exist for eluding disciplinary power or reconfiguring its archival systems in order to assert a degree of subjective autonomy or evade the determinations of power/knowledge.

Long’s study of Sebald is very much a description of modernity; in particular, of modernity as a series of affects of power and discipline upon the subject (again, very Foucauldian). It’s not particularly surprising then that Long, after locating so many Sebaldian traumas in the 19th and early 20th centuries, asserts that Sebald is a modernist and not a postmodernist. He bases this claim not on the formal elements of Sebald’s prose, which he readily concedes can just as easily be read as postmodernist, but rather on the way his “texts respond to the specific historical constellation” of modernity. Long continues–

Long’s study of Sebald is very much a description of modernity; in particular, of modernity as a series of affects of power and discipline upon the subject (again, very Foucauldian). It’s not particularly surprising then that Long, after locating so many Sebaldian traumas in the 19th and early 20th centuries, asserts that Sebald is a modernist and not a postmodernist. He bases this claim not on the formal elements of Sebald’s prose, which he readily concedes can just as easily be read as postmodernist, but rather on the way his “texts respond to the specific historical constellation” of modernity. Long continues–

What is notable about Sebald is that the fictional worlds he constructs are not postmodern spaces of global capital, hyperspace and ever-faster cycles of production, consumption and waste (despite his narrators’ occasional visits to McDonald’s). His texts do not present unrelated present moments in time, nor do they partake of the waning of history that is frequently noted as a characteristic of the postmodern. Sebald’s spaces are those of an earlier modernity that are deeply marked by the traces of history.

If the question of whether or not a book is postmodern or modern strikes you as merely academic, that’s because it is merely academic. Long makes a solid case for Sebald-as-modernist, but the best parts of his book are really his Foucauldian analyses of Sebald’s texts. They make you want to go back and reread (or, in some cases read for the first time.) I’m inclined to believe that Sebald (along with a host of other writers) is better described as something beyond modern or postmodern, something we might not have a name for yet, but that’s fine–we need distance, time. In Long’s take, Sebald is, of course, trying to sort out the detritus of modernity–even as it’s happening to him. But I’m not sure if that makes him a modernist.

W.G. Sebald: Image, Archive, Modernity is available now from Columbia University Press.

The Rumpus Interviews Tao Lin about Stealing Books (and Other Issues)

The Rumpus interviews Tao Lin. Topics include social media in literature, suicide, Jonathan Franzen (not really (but sort of)), as well as his new novel Richard Yates (read our review here). Lin answers plenty of questions about Richard Yates, including why he put an index in the book, why and how he named his protagonists, and why he named the book Richard Yates. Here’s Lin on book theft as a marketing tool–

Stephen Elliott: What if your books were shoplifted?

Tao Lin: I’m okay with that.

I think giving away free books and having more readers will benefit the publisher, because 1 free book will cause like 10 people discussing it, which over time will change into like 50 or something. Some of those will buy it. Eventually the 1 free book’s like $1.50 cost will be offset, gradually more and more, by the effects of that 1 free book on people buying it.

Reminder: David Foster Wallace Archive’s Live Webcast Tomorrow Night

A reminder for interested parties: the David Foster Wallace Archive at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas will début the collection tomorrow night at 8:00pm EST with a live webcast featuring readings of Wallace’s works. You can access the webcast here.

(Ed. note — We got the date wrong the first time. Thanks to @MattBucher for the correction!)

Tom McCarthy Reads from His Novel C (. . . and We Gripe about Michiko Kakutani)

At The Guardian, Tom McCarthy reads from his novel C. Here’s Biblioklept’s review of C.

And, while we’re on reviews of C, I want to gripe about Michiko Kakutani’s negative review of the book at The New York Times. If you don’t like a book, fine. But if you’re a critic at an organ that purports to be the nation’s beacon of journalistic excellence, you need to practice better criticism than what Kakutani’s done here. I think it’s pretty much a given that a critic should judge a book on its own terms–in terms of what the author was trying to do. Instead, Kakutani faults McCarthy’s book for not living up to a standard she finds in Ian McEwan’s Atonement, of all things–

But unlike Mr. McEwan’s masterpiece “C” neither addresses larger questions about love and innocence and evil, nor unfolds into a searching examination of the consequences of art. Worse, “C” fails to engage the reader on the most basic level as a narrative or text.

Kakutani provides no real evidence for that second claim but I’ll let that alone for a moment, simply because I think she’s wrong, and that she doesn’t bother to back her subjective judgment reveals a rushed reading. What really bothers me though is this idea that C was supposed to address “larger questions about love and innocence and evil”–where did she get that idea? She tells us where she got it: a novel by Ian McEwan.

Here she is again dissing McCarthy for not meeting the Kakutani standard–

Although Mr. McCarthy overlays Serge’s story with lots of carefully manufactured symbols and leitmotifs, they prove to be more gratuitous than revealing.

Just what was the novel supposed to reveal to Kakutani? The same mysteries that McEwan plumbed in his earlier novel? Why, exactly? One of C’s greatest pleasures is its resistance to simple answers, to its willingness to leave mysteries unresolved (I believe this is what Keats meant by negative capability).

Kakutani devotes a few sentences to C’s dominant theme of emerging technology and communication–

As for the repeated references to radio transmissions and coded messages sent over the airwaves, they are apparently meant to signal the world’s entry into a new age of technology, and to underscore themes about the difficulties of communication and perception, and the elusive nature of reality. But while the many technology references also seem meant to remind the reader of Thomas Pynchon’s use of similar motifs in “Gravity’s Rainbow,” Mr. McCarthy’s reliance on them feels both derivative and contrived.

Notice how instead of talking about McCarthy’s novel she retreats to another novel? Why? Why does she assume that C is echoing Gravity’s Rainbow? This isn’t a rhetorical question–she doesn’t bother to tell us. She just uses Pynchon’s book to knock McCarthy’s, not to enlarge any analysis of it. That is the laziest form of criticism.

The New York Times did better by publishing a review of C by Jennifer Egan this weekend. Egan’s review is positive–and I loved C–but that’s not why the review redeems the Times’ standard. Egan’s review actually considers the book, discusses its language and themes, and tackles it on its own terms. When Egan does reference another book–Dickens’s David Copperfield–she does so in a way that enlarges a reader’s understanding of McCarthy’s project–not her own ideal of what a book should be.

Hear James Ellroy Read from His New Memoir, The Hilliker Curse

Listen to James Ellroy read from his new memoir, The Hilliker Curse (audio clip courtesy Random House Audio).

Gainesville Pastor Backs Down on Burning Qu’ran

USA Today and other sources report that Terry Jones will cancel his September 11th book burning, claiming that he reached an agreement to have the so-called “Ground Zero Mosque” moved to another location. This all seems kind of nebulous.

David Foster Wallace Archive Will Open with Live Webcast

The Independent reports that the David Foster Wallace Archive at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas will debut the collection with a live webcast on September 14, 2010 featuring readings of Wallace’s works. You can access the webcast here. (But, like, obviously not until next Tuesday night).

The AV Club Interviews James Ellroy

The AV Club interviews noir postmodernist James Ellroy about his forthcoming memoir, The Hilliker Curse. Here’s Ellroy, the cranky old man–

I very much enjoyed the process of interdicting the culture. I’m older; I have a great love of the English parlance. I can’t stand dipshit, tattooed, lacquered, varnished, depilatoried younger people talking their stupid shit, stage-sighing, saying “It’s like, I’m like, whatever,” and talking in horrible clichés, rolling their eyes when they disapprove of something. I saw that the culture was pandering more and more to this kid demographic. And in the course of driving from here to there, I began to see more and more billboards for vile misogynistic horror films, white-trash reality-TV shows, neck-biting fucked-up vampire flicks, and stoned-out teenage-boy pratfall comedies. Bad drama, bad comedy, that portrayed life preposterously, frivolously, and ironically, and that got to me. So I would drive here, there, and elsewhere through residential neighborhoods in order to avoid billboards. Since I wasn’t married and had no more in-law commitments, and was starting over again in a new locale, I developed strong friendships with male colleagues where we share the common goal of work and earning money, and I became fixated on women in my late 50s more than I’ve ever been fixated on women in my woman-fixated fucking life. My time in the dark felt productive rather than reductive, and the rest of the chronology, you know from the book. And I’m comfortable living in this manner, which people find hard to believe that I’m happy. It’s a gas. It’s a gas.