I don’t really know if there’s anything new I can say about Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury in a blog post, and I’m not in the practice of writing term papers here, and you wouldn’t want to read one anyway. I’ll cop out and be vague but honest: the book was astounding and exhausting. I’ve read a number of Faulkner novels now, and The Sound and the Fury was easily my favorite. I’d attempted it a few times before, only to be thwarted by an inability to commit to the sustained concentration required to comprehend Faulkner’s stream-of-consciousness technique. The first section of the book, told from the perspective of Benjy, the seminal Faulknerian idiot man-child, is particulalry daunting, especially if you have no prior knowledge of the story of the Compson family, and I don’t think I would’ve made it through this reading if I didn’t arleady know the major themes and the trajectory of the plot. I’m actually kinda sorta shocked that the book was published at all, and I really wonder about its earliest audiences–how much context did they have? What guided them through the verbal detritus of the book’s first half?

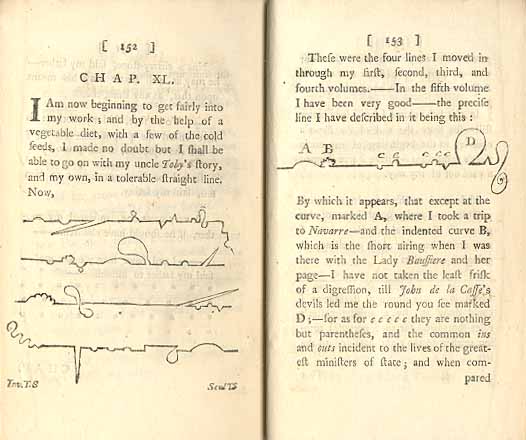

I suppose that at the time of its publication in 1929, literary audiences were at least somewhat familiar–if not wholly intrigued by–the stream-of-consciousness technique pioneered in books like James Joyce’s Ulysses and Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway. I read both of those books years before The Sound and the Fury, and I would make a subjective argument that they are quite a bit easier to enter into in terms of linearity and plot structure. Also, reading TSatF, I couldn’t help but feel the subtle resonance of Ulysses, particular in the constant use of omission. One of the things that makes Ulysses challenging is that Leopold Bloom frequently elides specific referents–we often get a “him” or a “he” or a “she” or an “it” without immediate context. Often, that context comes much, much later in the novel, with the net result that at times Bloom’s stream of consciousness is awfully ambiguous. Other times, Bloom seems unable to even think the words that would name the tragedies of his life (his dead son, his unfaithful wife, his outsider status in Dublin). Similarly, Faulkner’s Compsons are unable to directly name their own tragedies of promiscuity, suicide, alcoholism, madness, and financial decline. The effect is disarming and immediate, and while it can be very engaging, I can see how many readers would be alienated to the point that they can’t finish the book. I think there are a few simple solutions to the intrinsic problems of reading The Sound and the Fury, and at the risk of looking like a didactic asshole, I’ll share:

1) Read a brief plot summary first. I took a graduate seminar on Faulkner from which I gleaned the basic plot points and themes. (Ironically, the seminar assumed that any English major in grad school would have a working knowledge of the book, and instead focused on lesser-read volumes like Intruder in the Dust). Knowing the background of the Compson family did not ruin reading the book for me, nor did it replace an actual reading of Faulkner’s language–it simply gave me enough of a frame of reference not to throw up my hands in despair.

2) Read quickly and in long sittings. This is not a book that you can pick up and read a few pages of each night. Each chapter has a distinctive rhythm, and it takes a few pages to get into the pace and perspective of the chapter. I read the book in about eight sittings. I also found TSatF impossible to read at night before I was about to go to bed.

3) Don’t worry about getting everything in the first reading. Not possible. Enjoy the language, its strangeness. Marvel at Faulkner’s attempts–both successful and unsuccessful–to transcend time, space, and place. If you’re not enjoying it, why bother reading it?

Most of these suggestions could be applied to Ulysses as well. I brought up the possible influence of Joyce on Faulkner and I was interested enough to do a little research. The following text is from pages 208-209 of A William Faulkner Encyclopedia by Robert Hamblin and Charles Peek, and I think it neatly summarizes the issue:

When asked about the influence of Joyce on his own writing during the early years of his fame, following the publication of The Sound and the Fury and As I Lay Dying, Faulkner tended to be understandably evasive. In a 1932 interview with Henry Nash Smith, for example, Faulkner claimed, in fact, that he had never read Ulysses, invoking instead a vague aural source for his knowledge of Joycean methods: ” ‘ You know,’ he smiled, ‘sometimes I think there must be a sort of pollen of ideas floating in the air, which fertilizes similarly minds here and there which have not had direct contact. I had heard of Joyce, of course,’ he went on. ‘Some one told me about what he was doing, and it is possible that I was influenced by what I heard’ ” (LIG 30). In a moment of irony that may not have been lost on the interviewer, Faulkner reached over to his table and handed Smith a 1924 edition of the book. . . By 1947, Faulkner hardly needed to be so coy, telling an English class at the University of Mississippi that Joyce was “the father of modern literature” (1974 FAB 1230). By 1957, Faulkner’s pronouncements on Joyce had become fully classical: “James Joyce was one of the great men of my time. He was electrocuted by the divine fire” (LIG 280).

“Electrocuted by the divine fire” . . . very nice.

Nice gear shift…

Nice gear shift… Love the enthusiasm there…

Love the enthusiasm there…