So this Friday, I bought two enormous fat thick Penguin volumes of Jorge Luis Borges in utterly pristine condition (fictions and non-). I own other books that cover some of the material here, but 1100+ pages of JLB is hard to pass up (especially used, especially when I have store credit).

And then today, I was made privy to this lovely Flickr set, “Things found in books,” and thought I’d play along.

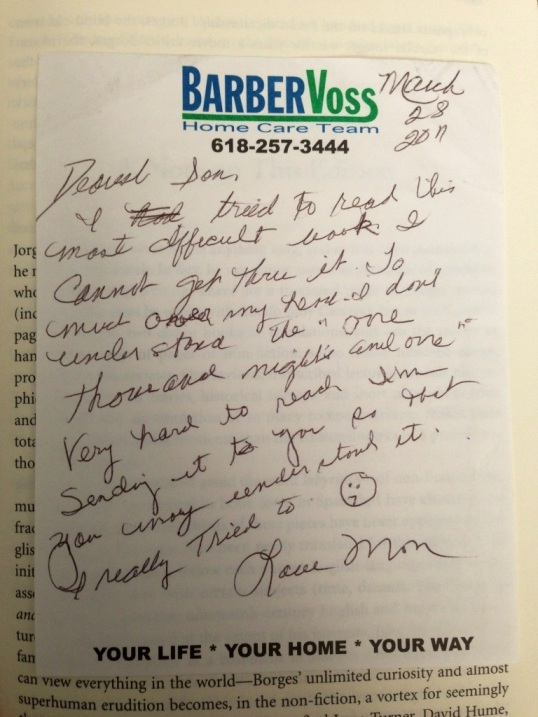

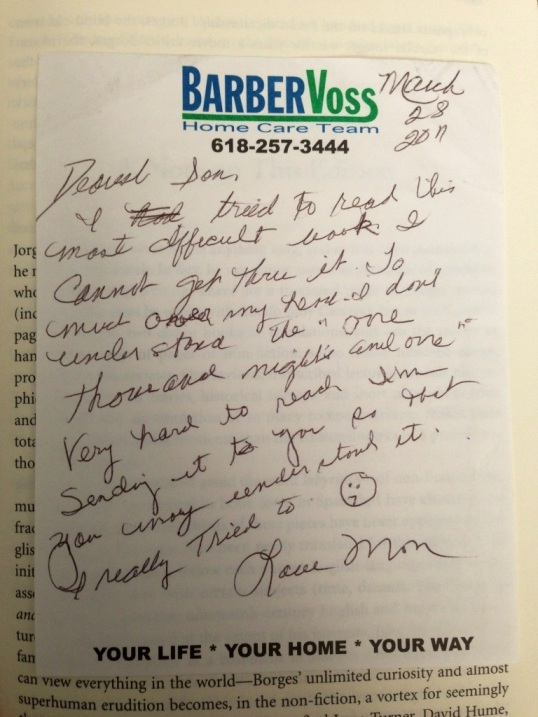

So back to Borges: I was somewhat touched by this note (above) I found in the nonfiction collection: Mom sends the book to her son so he “may understand it,” “this most difficult book”; mom also reports it “very hard to read” and appends a frowny face.

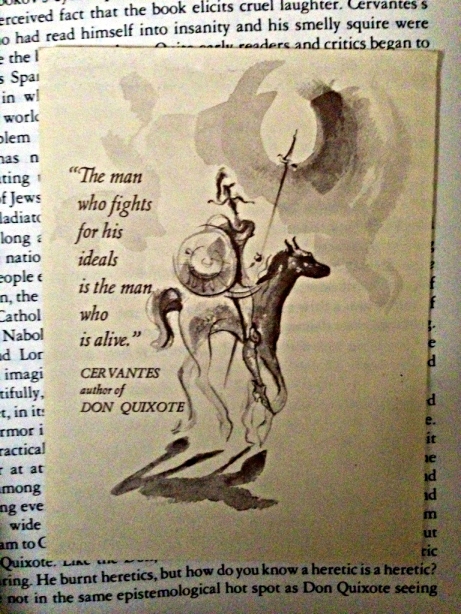

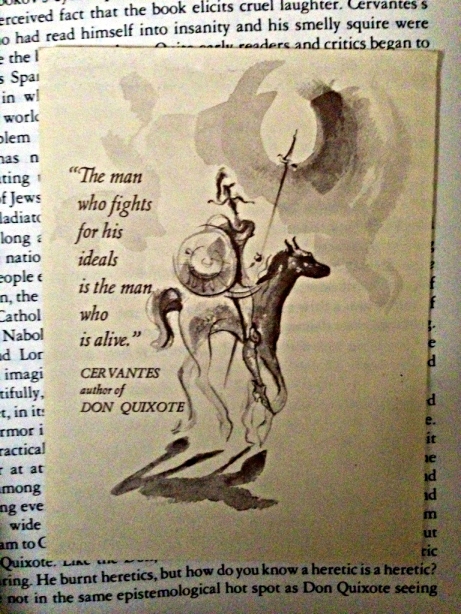

Maybe a week or two before, I found this lovely little wisp of paper:

In Vlad Nabokov’s Lectures on Don Quixote:

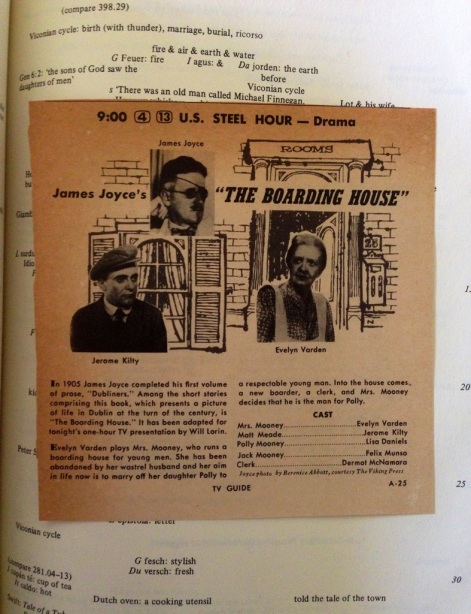

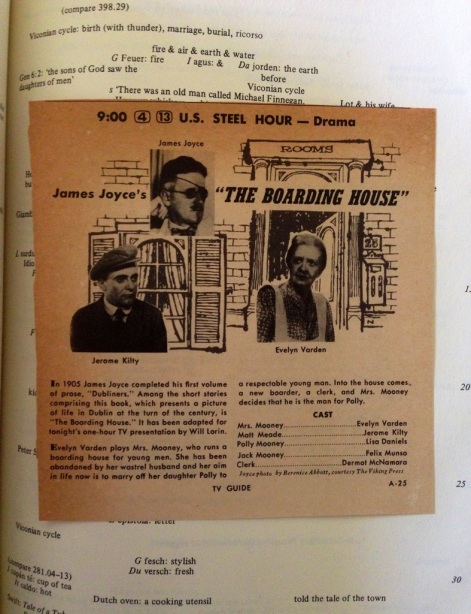

Which reminded me of this James Joyce clipping—not so recent, I’ll admit, but still carefully placed as a bookmark in a Finnegans Wake guide:

Okay, annotations, more properly:

Do most people leave stuff in books? I think most bibliophiles do. (Forgive the snobbish italics there. I’m sure there are bibliophiles who don’t, of course). I have a habit of never reusing a bookmark, so that when I pull out a volume there’s some little tag there that acts as a third point (along with the text and my addled brain) to help triangulate the reading experience (the concrete circumstances of the reading process, the where, the when, the how much, etc.).

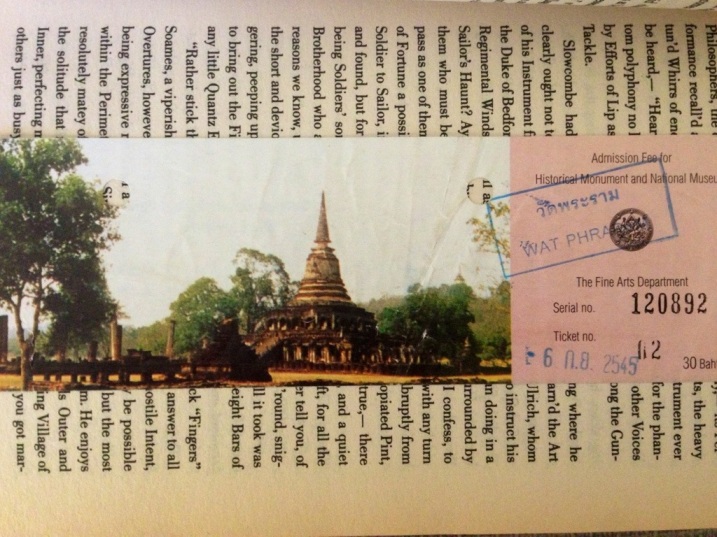

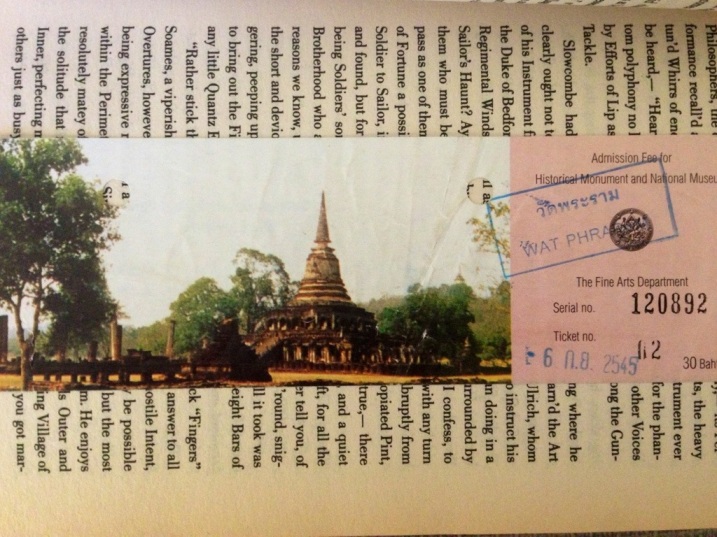

And so, after finishing Pynchon’s Against the Day a few weeks ago, I resolved to return to Mason & Dixon. Pulling out my copy, where I found an entry ticket to Wat Phra Ram in Ayutthaya. I’m pretty sure I bought the book in Chiang Mai (after buying V. in Bangkok; books were the only thing I ever thought were expensive in Thailand).

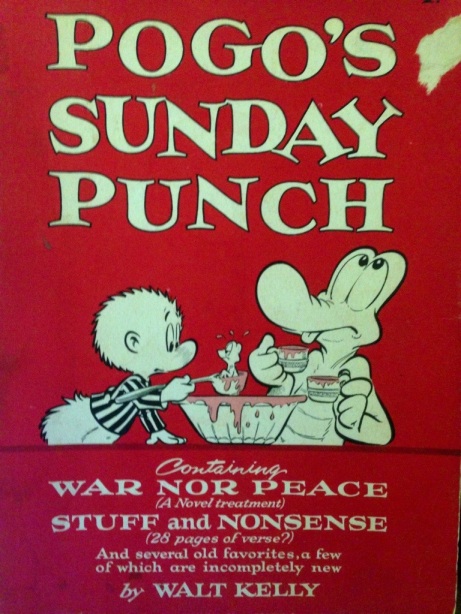

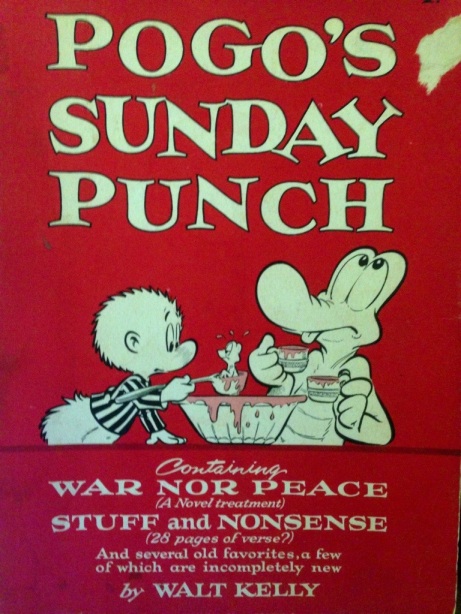

A few weeks ago my grandmother let me take one of my grandfather’s favorite books with me when I left her house, a Walt Kelly collection.

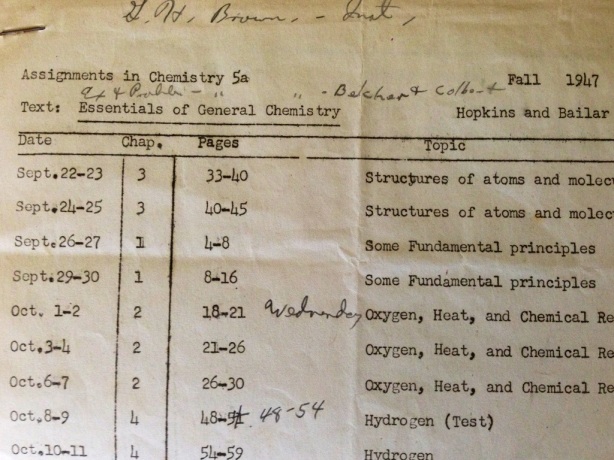

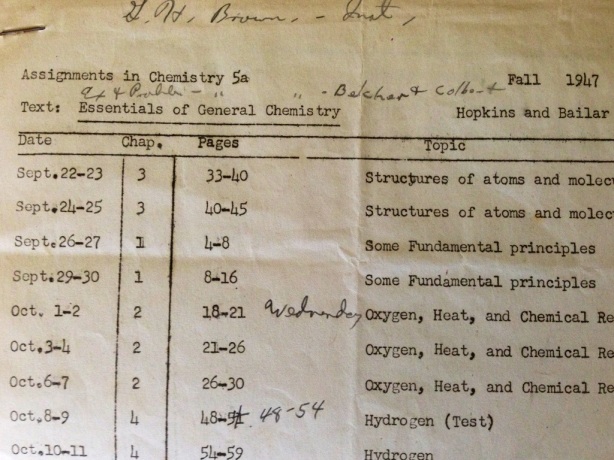

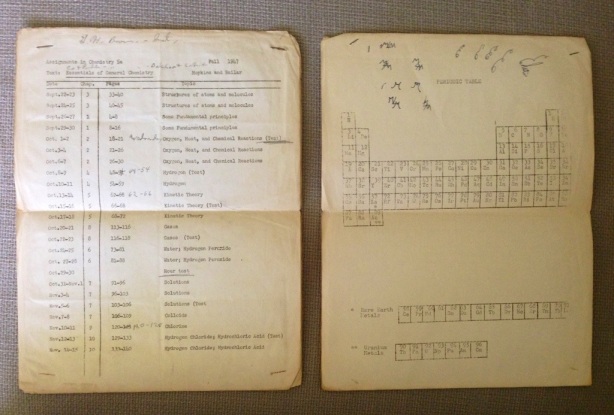

I was thrilled to find inside the Pogo volume the syllabus of my grandfather’s college chemistry class from the Fall of 1947:

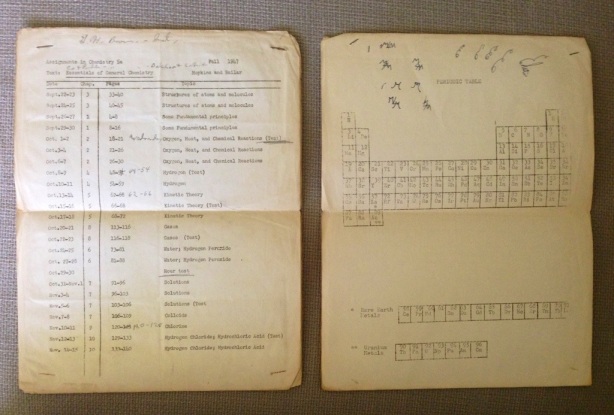

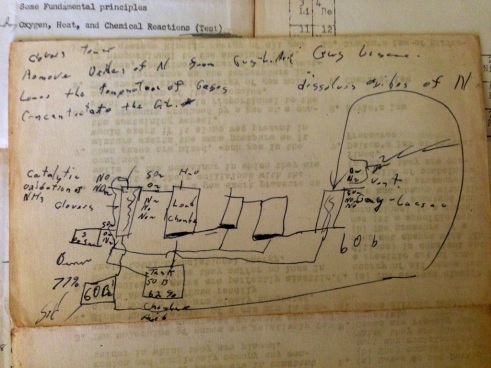

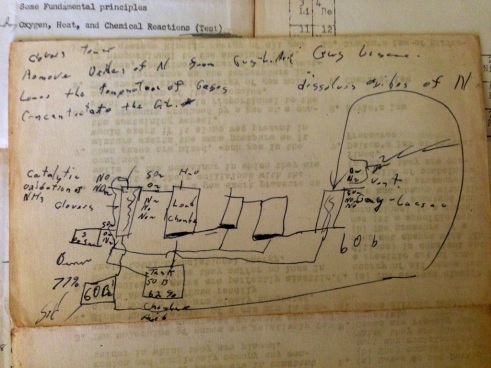

And some of his notes (cryptic to me, but endearing):

I think the best part about finding my grandfather’s old syllabus tucked away into a book he loved is knowing that we shared a habit.