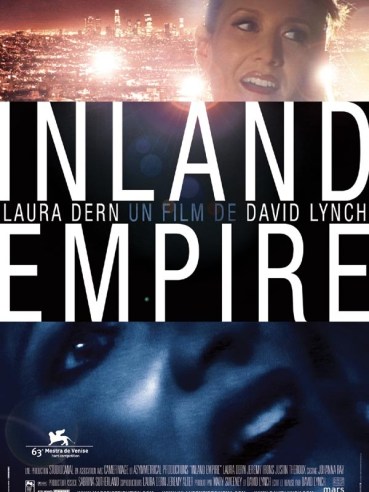

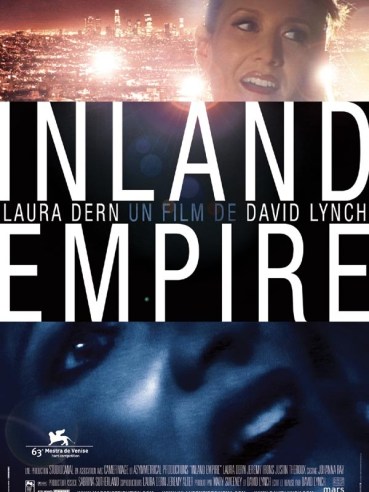

There’s so much going on in David Lynch’s INLAND EMPIRE that I’ll give you the quick review up front: if you like David Lynch films (I do), you’ll love this film (I did)–it’s arguably his most ambitious to date and belongs in the canon of great Lynch films along with Blue Velvet and Mulholland Dr. Get a hold of it and watch it right away. If you don’t like David Lynch films, you won’t like INLAND EMPIRE–but you already knew that, didn’t you?

Contrary to some of the internet rumors and poorly conceived reviews out there, INLAND EMPIRE actually does have a plot, complete with an honest-to-goodness resolution full of redemption and love. However, the fragmentary and elliptical nature of the film will no doubt confound anyone who tries to actively resist it: like Mulholland Dr. before it, this is one you need to just let happen to you. Attempts to impose your own system of narrative logic will probably result in headaches and frustration. You see, INLAND EMPIRE is really a time-travel movie, and time-travel movies–the good ones–are always resistant to narrative logic (see the Grandfather Paradox, etc.).

The story begins with a gypsy-witch’s curse: she visits actress Nikki Grace (played by Laura Dern who appears in almost every scene of the movie, and is truly fantastic) and warns her about the coveted film role she’s about to land. It turns out that the film, On High in Blue Tomorrows, is a remake of a Polish film called 49 that was never finished because the two leads were murdered. “If it was tomorrow,” the gypsy croaks, pointing across the room, “you would be sitting over there. Do you see?” And Nikki does see: the rest of the film may or may not be a vision prompted by the gypsy. However, my phrase “The story begins” at the beginning of this paragraph was not entirely accurate: before we even meet Dern’s character, we see a light projection and a phonograph needle, a weeping woman trapped in a room watching a chilling sitcom starring bunny people (INLAND EMPIRE thus gets to go on a special list of movies featuring scary rabbits, including favorites Donny Darko and Sexy Beast), and a strange scene with a Polish prostitute.

So there are plenty of frames to this frame-tale, and the narrative only continues inland as the movie progresses, exploring a multiplicity of spaces and times. Dern’s Nikki morphs into new and different characters–housewives and hookers–even as she passively stands on the wall, a frightened voyeur robbed of all agency. And in many ways this is the major theme of the movie: how to find agency and self-determination in a world where time and place–context–are the main components and constituents of identity. INLAND EMPIRE breaks down the lines between actors and prostitutes and really any other job, suggesting that perhaps we all have some identity as a whore, an identity thrust on us by location and time, an identity that we are always struggling against.

But this is really just one of many themes in the movie. The usual Lynch tropes are here: pop nostalgia with a sinister tinge, stilted dialog, lush red curtains, characters that seem of vital importance who never show up again, cryptic symbols that may or may not be symbols at all, etc. etc. etc. Despite its three hour running time, INLAND EMPIRE never lags or sags, in large part because so much weird stuff is going on, but also because in many ways this movie is a distillation of every other Lynch film: we get the murder mystery of Twin Peaks, the abuse-of-women theme inherent in Blue Velvet, the Wizard of Oz riffing from Wild at Heart, the voyeur-terror of Lost Highway, the Haunted Hollywood and doppelganger mindfuck of Mulholland Dr., and the general creepy weirdness that’s underscored every Lynch film since Eraserhead.

INLAND EMPIRE is shot entirely on digital video, a format that Lynch swears is the future of cinema. I’m not sure about that–although his movie is a beautiful masterpiece of textured light and composition, not all directors are painters like Lynch; in someone else’s less-gifted hands this movie could’ve been, visually speaking, a muddled mess. Still, it seems for now Lynch is determined to continue shooting on DV.

A couple of days before I saw INLAND EMPIRE, I heard most of an interview with Lynch on NPR’s Talk of the Nation. Neil Conan asked him what the last great movie he saw in the theaters was, and, to my surprise, he said that it was The Bourne Ultimatum, a movie he touted as being “excellent” or “perfect” or something like that. At first this struck me as odd–Lynch going to see a pretty straightforward–albeit smart–action movie? But on further reflection there’s nothing odd about this. I think that Lynch sees his films not as outsider films or art films per se, but as something more akin to the Hollywood tradition–I’m sure he’s not deceived that his films are as accessible as the Bourne films, but I do believe that he is a pop artist (or Pop Artist, if you prefer)–he had a huge hit television show, didn’t he? And INLAND EMPIRE not only fits in with Lynch’s growing pop art legacy, it could be the masterpiece of his oeuvre. Let’s hope that that legacy continues to grow; INLAND EMPIRE suggests an artist in his prime who will continue making great films.