I’ve been lucky over the last decade or so that my little college’s spring break almost always coincides with my children’s spring break. We aimed again this year at Georgia, spending a few days in a cabin outside the unfortunately named Whitesburg. Spring had not yet really sprung there yet. There was very little green about, but the hikes along and around Snake Creek through 20th century ruins were pleasant enough, and the kids enjoyed ziplining and aerial obstacle courses. In one of their sessions, I sneaked away to Harvey’s House of Books.

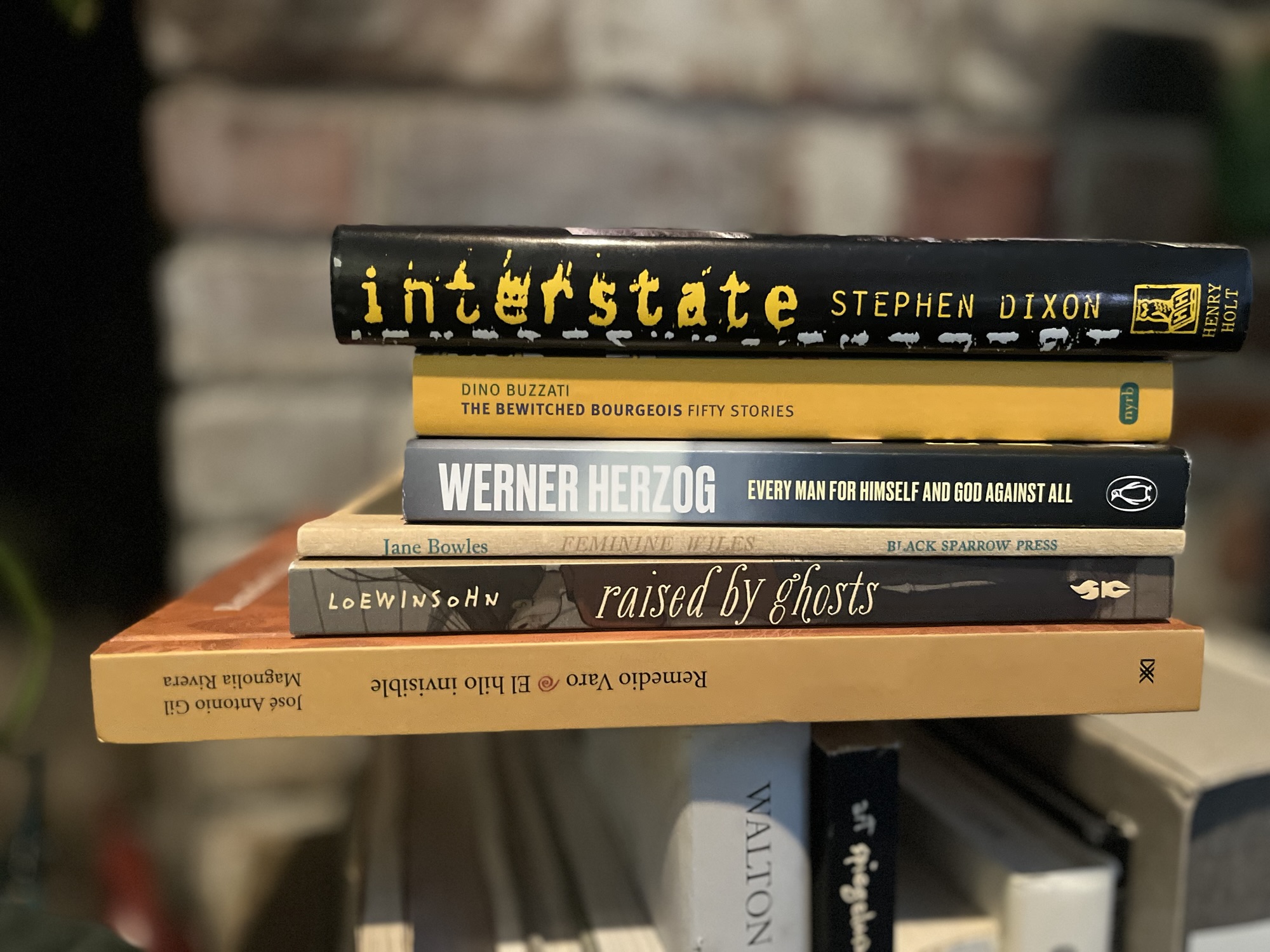

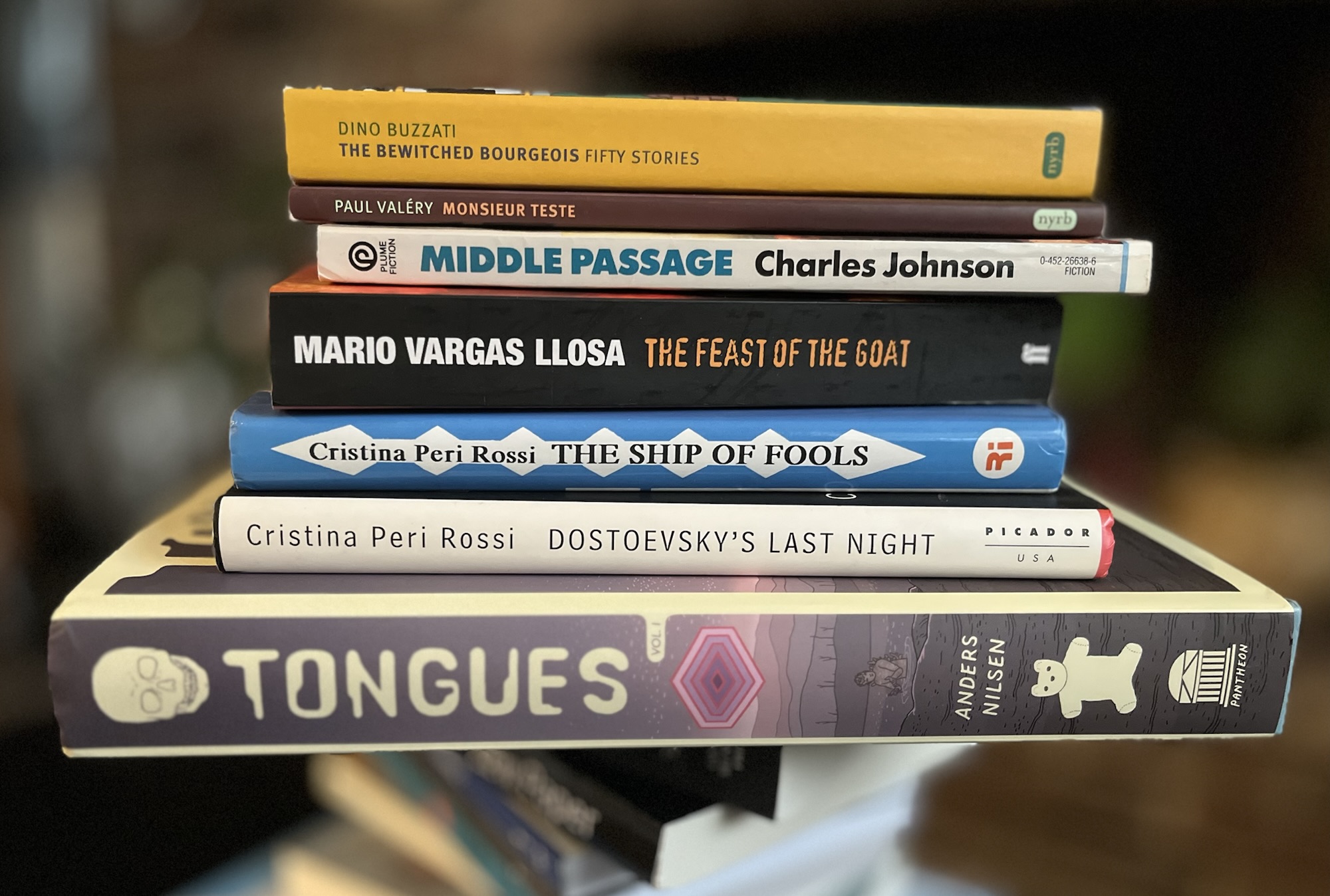

Harvey’s is, as far as I can tell, a Friends of the Library venture run by volunteers. I didn’t expect much, but the fiction section was surprisingly well populated. For around five bucks I picked up Charles Johnson’s Middle Passage, Mario Vargas Llosa’s The Feast of the Goat, and two by Cristina Peri Rossi — The Ship of Fools and Dostoevsky’s Last Night.

I was happy and surprised to find Rossi’s The Ship of Fools (in translation by Psiche Hughes); I’ve had it on a mental list for a few months now. I started it that night and it’s really odd–reminds me a bit of Ann Quin’s stuff, very odd but fun. More thoughts to come.

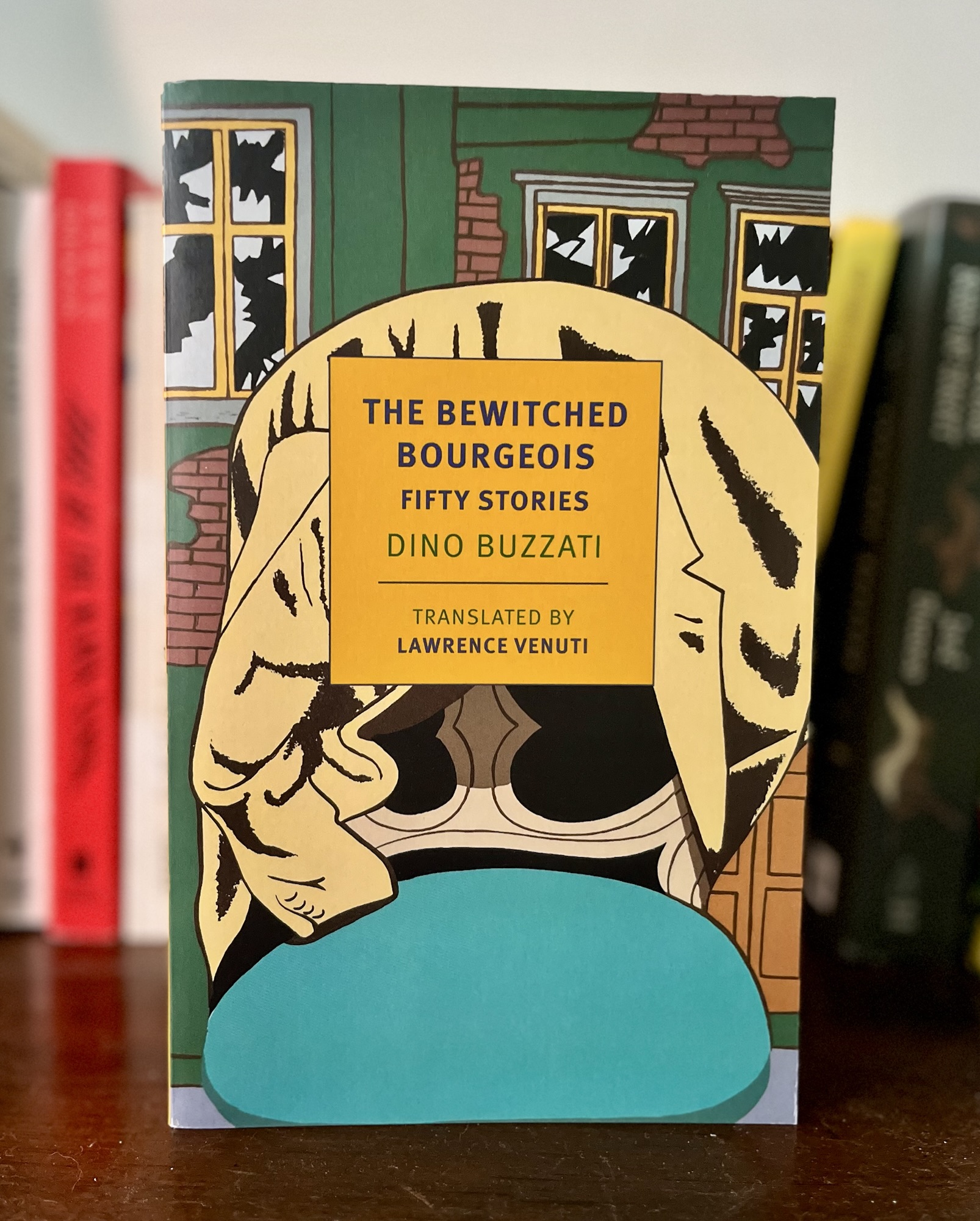

The Ship of Fools proved a nice antidote to the books I’d brought with me, Paul Valéry’s Monsieur Teste, (in translation by Charlotte Mandell) and a Dino Buzzati collection translated by Lawrence Venuti, called The Bewitched Bourgeois. I’ve enjoyed the Buzzati stories, but piled up there’s a sameness here that cries for interruption. I love Borgesian riffs on “Before the Law” as much as the next nerd, but too many in a row (six, in my case this week) feels, I dunno, like, I get it. But to be clear, I’ve really liked most of The Bewitched Bourgeois. I think it’s better parceled out though. Monsieur Teste on the other hand…look, I don’t know, maybe I misunderstood the book entirely, but I really kinda sorta hated it. Was I supposed to hate the central persona, Mister Teste, who aims for precision in language but comes off as a bore? At least it was short.

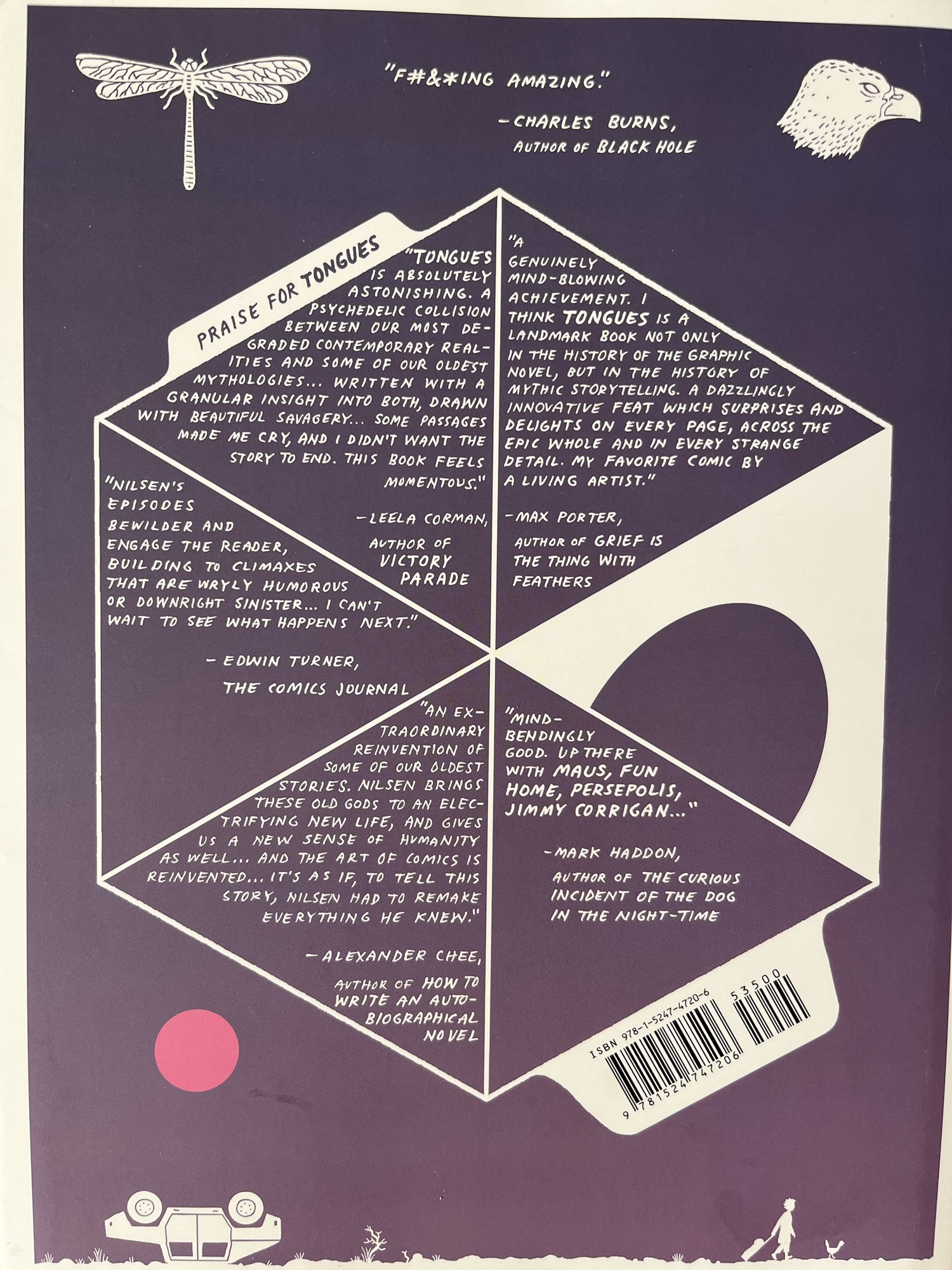

While I didn’t have the time in Atlanta to hit multiple bookstores (like in past trips), I made a point to hit up A Capella Books, a well stocked indie joint with a great used collection. I didn’t score anything there, although I was thrilled to see Anders Nilsen’s Tongues prominently featured in the graphic novel section. The book is great — I got a review copy right before we left. Some asshole named Edwin Turner landed a blurb on the back under his hero Charles Burns’s much shorter, pithier, better blurb:

Our spring break culminated Saturday night at the Variety Playhouse in Little Five Points, where we saw the so-called indie supergroup The Hard Quartet play all of their songs. I really dig The Hard Quartet’s self-titled debut, and dragged my wife and son along. (My daughter declined but played taxi driver.) Some interesting looking children were exiting the theater (really more of a club, let’s be honest) as we were entering, assuring the concerned security guard that they’d be right back, they just needed to get some Gatorade at a corner store. These were Sharp Pins, or The Sharp Pins, or Thee Sharp Pins, a Chicago power pop trio fronted by a kid named Kai Slater. They played a tight thirty minute set (including a Byrds cover); young Slater knows how to tuck away middle eight. The band’s youth invigorated the crowd of indie oldheads, and if Sharp Pins were occasionally a little out of tune or a step behind on the count, what came through was a true joy for the pop song. My son went bananas from them, saying something like, I know that they aren’t as good at playing their instruments as the Hard Quartet guys, but I liked their songs more. He bought their album and their t-shirt.

I liked The Hard Quartet’s live show very much — these are some old, or let’s just say older guys — look, pretty much everyone at the show was old, older, etc., except the Sharp Pins, my son, and some other teens there with their folks — these guys, the HQ, are veterans of disorder, coming up in club shows and theaters and big stages and big big stages and so on. They seemed very comfortable in the quasi-theater club. It was a joy to watch and listen to them.

They are, as I mentioned before, a so-called “supergroup.” Stephen Malkmus was the sideman for David Berman in The Silver Jews; Matt Sweeney, a popular YouTube influencer, was a member of another infamous supergroup — David Pajo’s short-lived side project Zwan; Emmett Kelly is a former gang member and circus performer; Jim White is the best drummer I’ve ever seen live (I have no stupid joke here; he is amazing and I listened to Ocean Songs every night for two years in a row when I was 22 and that’s not an exaggeration.)

The Hard Quartet are clearly a “real” band and not anyone’s side project. Sonics live were richer, fuller, more expansive than on disc. Emmett Kelly sang his new song, which, as far as I can tell, is the only update to their setlist in the past year — basically the record played straight through — but they seemed to never remember who was playing bass on which song when. No one used a pick, ever, as far as I could tell. Sweeney broke a string and then claimed he’d never broken a string on stage, ever. (Dubious.) Malkmus said he was thinking about “The Devil Went Down to Georgia,” but, what if it was, like, “The Devil Went Down on George.” Sweeney jokingly referred to Charlie Daniels as Chuck Daniels and at least two Atlanta audience members hissed foolish rejoinders. (Could’ve been those big beers, bald boys!) Jim White is both a gentle percussionist and a rawk gawd drummer. Malkmus’s, Kelly’s, and Sweeney’s singing in unison were some of the finest moments of the night, as in “Rio’s Song” and “Heel Highway.” The band’s weathered implementation of silence and space was also delicious and judicious in numbers like “Six Deaf Rats,” “Action for the Military Boys,” and “Hey.” Skronk and noodling were measured but never mannered. (Or the manners were there but they weren’t bad, unless they were meant to be bad.) Matt Sweeney’s left foot was the boss of the band, the bandleader, the clapper clopping down the count in a leopard print.

The Hard Quartet finished before eleven, having played all their songs. I think we all had a good time.