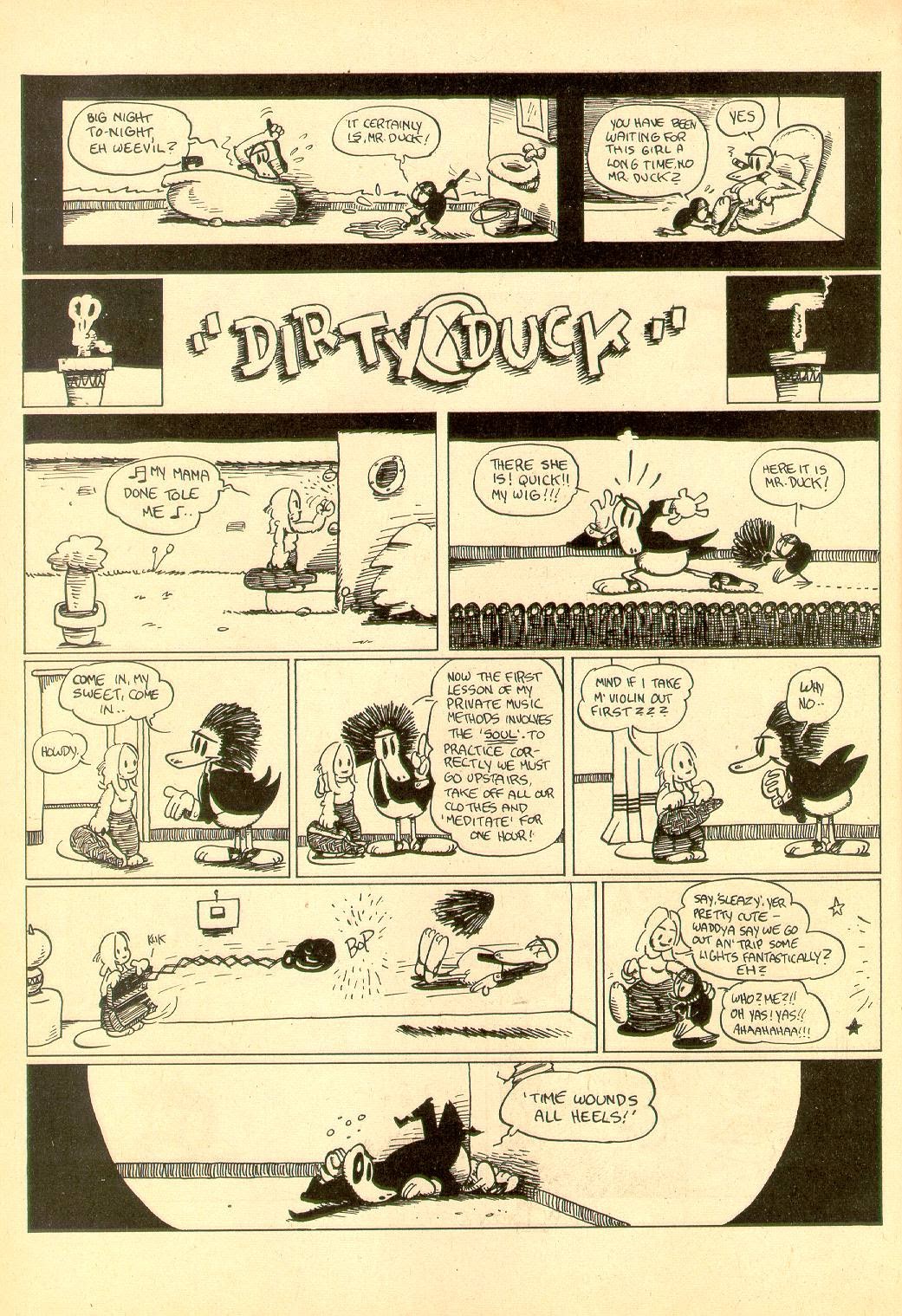

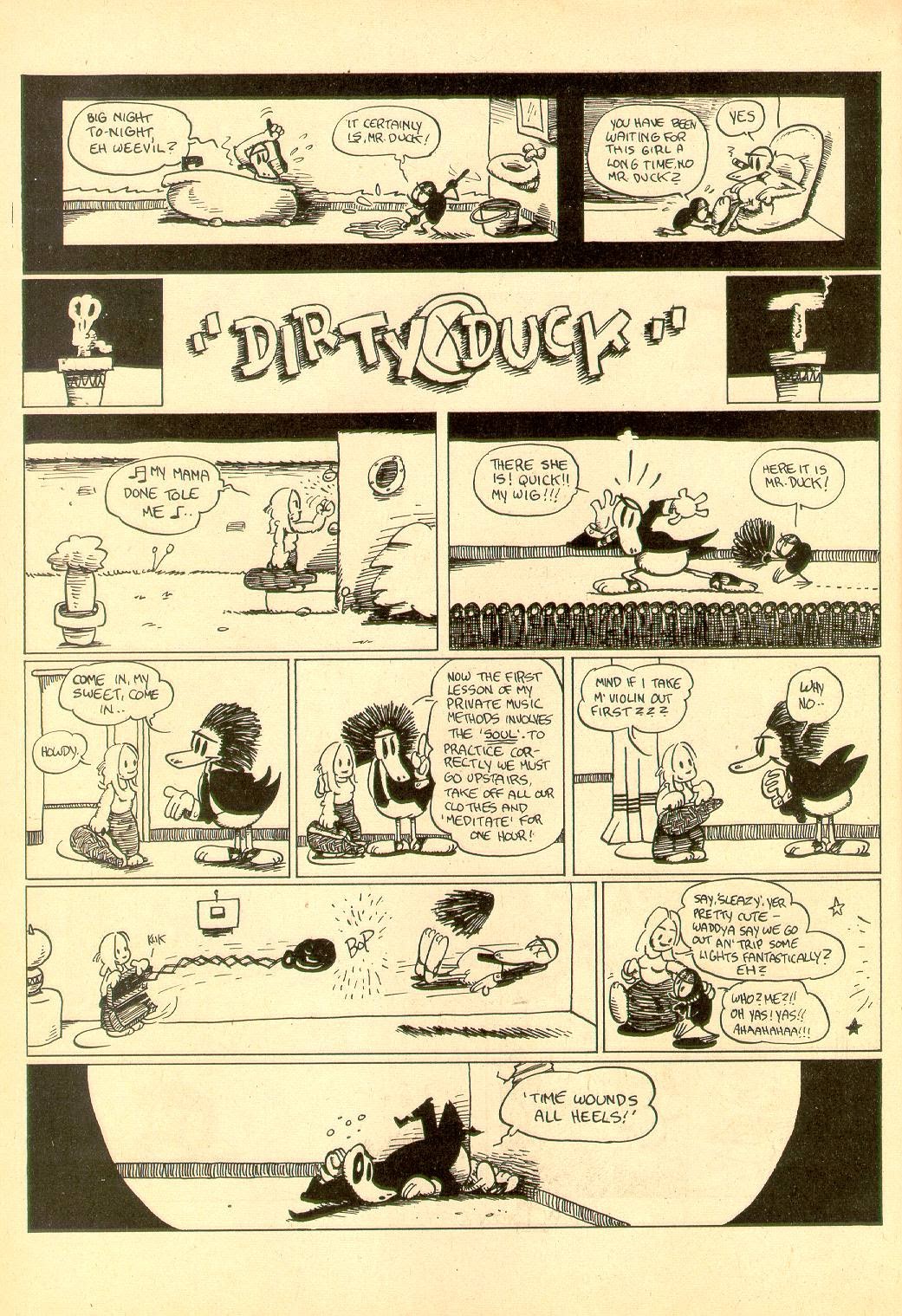

A “Dirty Duck” strip by Bobby London. From Air Pirates Funnies #1, July 1971, Last Gasp.

A “Dirty Duck” strip by Bobby London. From Air Pirates Funnies #1, July 1971, Last Gasp.

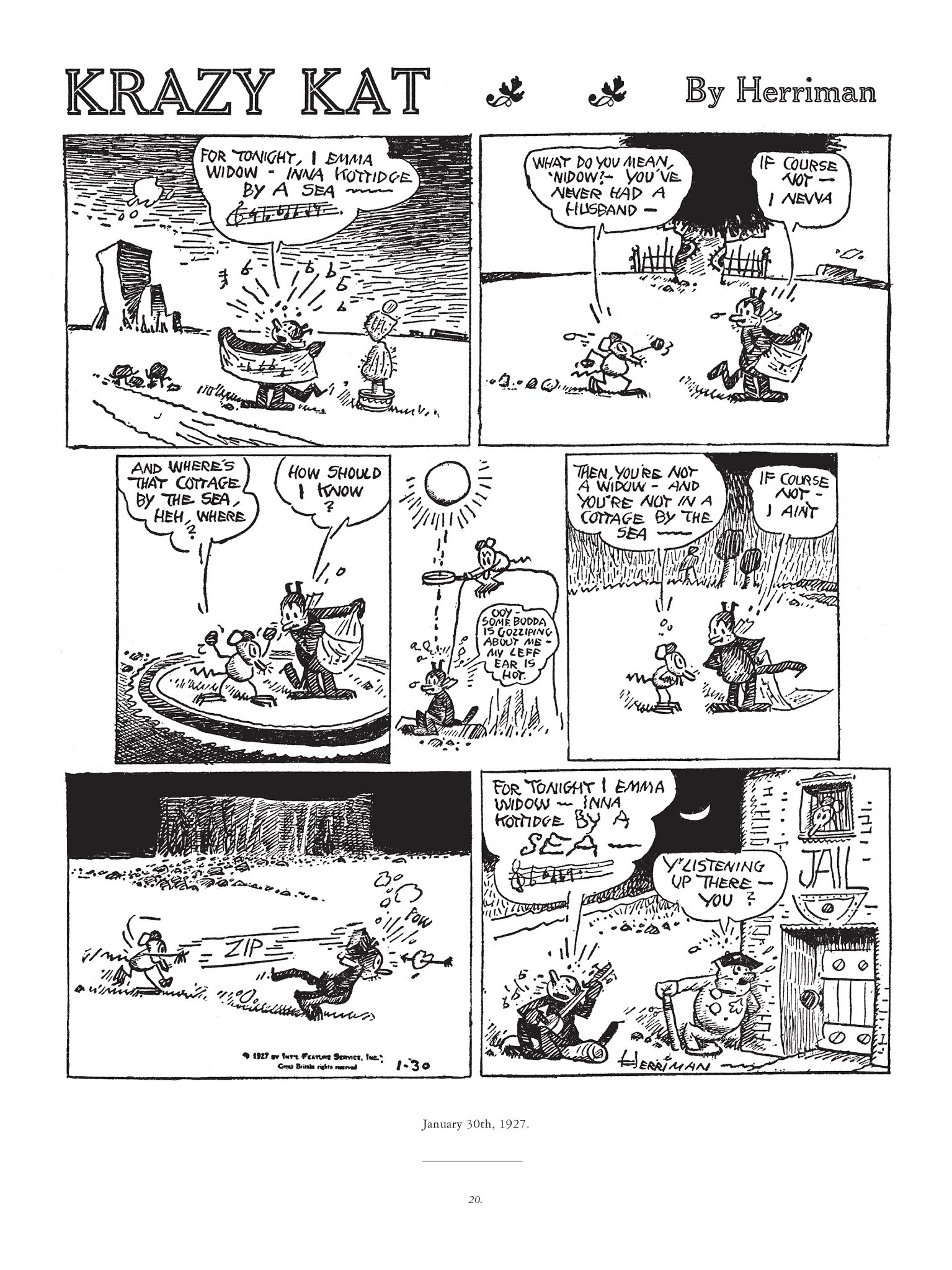

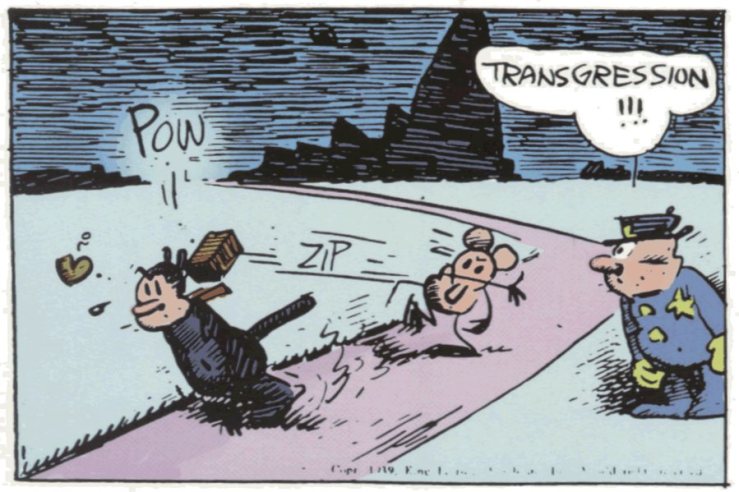

Krazy Kat, 30 Jan. 1927 by George Herriman

Drew Lerman’s comic strip Snake Creek takes us into the world of best pals Roy and Dav, weirdos among weirdos in Weirdest Florida. Their adventures and misadventures are both absurdly comic and zanily tragic, calling to mind George Herriman’s Krazy Kat strips and Samuel Beckett’s pessimism, Walt Kelly’s primeval Pogo and Robert Coover’s jivetalk, all rendered in kinetic black ink four-panel doses. I’ve been a big fan of the strip for a few years now, and Lerman’s latest collection Escape from the Great American Novel is his best work to date, a fun, messy, spirited send-up of the relationship between art, nature, and commerce.

Escape from the Great American Novel is a novel in just over 150 strips, spanning the end of August, 2019 through the beginning of August, 2021. If you reflect on those dates for a minute, you might recall that we squeezed in a lot of history there. Many of the (so-called) real-life tensions of that tumultuous time bubble up (and occasionally erupt) in the zany, myth-elastic world of Snake Creek.

Things begin simply enough, with Dav seeking to reclaim his “status as a reader of books.” Our protagonist simply wants to dig in to fine literature, but news of approaching Hurricane Dorian blocks his book time. Lerman is a Miamian (a Floridian like myself), and although the world of Snake Creek reverberates with massive streaks of irreality, it is nevertheless also beholden to real-life forces of nature. Ever the slackers, Dav and Roy are ill-prepared for an impending Cat 5. Lerman lays out a comedic scene that might be familiar to anyone who’s tried to buy batteries and water and plywood at the last minute:

The early Dorian episodes of Escape usher in a critique of capitalism-as-religion, or capitalism-as-philosophy (as opposed to, say, the naked reality of exploitation both of people, animals, and natural resources). Short on capital or material, Dav and Roy concoct a plan to forge receipts, totems of capital that might ward off the angry Nature God Dorian. Lerman sneaks in a reference to the erstwhile hero of William Gaddis’s 1955 novel The Recognitions, the forger Wyatt Gwyon:

The storm passes, post-hurricane sobriety settles in, and Dav finds himself reflective: Just what is he doing with his life? And, maybe more to the point, what can he do to extend that life into immortality? His solution, immediately ridiculed by friend Roy, is to commit himself to writing The Great American Novel:

Dav’s quest takes a solipsistic turn. He plays the tortured artist, his ambition a block to his actual progress in writing The Great American Novel. Lerman satirizes the over-inflated but self-defeating ego of the artist who aspires to surpass all the great works came before him. While the pratfalls of a would-be tortured artist is not a particularly fresh subject matter, Lerman brings vitality to his depiction of Dav’s struggle against the anxiety of influence. If we enjoy mocking Dav, it’s because we understand and empathize with him. Who doesn’t want to contend with the greats?

Dav’s quest also takes a turn away from his shenanigans with Roy. The pair’s riffing has always been the heart of Snake Creek, but Lerman keeps his partners apart for much of Escape. Dav’s dive into writing (or preparing to write, or preparing to prepare to write) distract him from Roy time. Initially, Dav chugs out reams of pages in the thrill of early enterprise. His ego swells, inflated by the grandeur of his illusions:

Only a few strips later, we find Dav’s illusions deflated. “S’all trash!” he declares over the mess of his nascent manuscript. Roy tries to help Dav. Snake Creek folk are all riled up over the plans of some “ollie garx” and the people are protesting. Roy rightfully recognizes potential inspiration here. He can bring his pal back to earth. “Sum sorter politicka thing” is happening, and that might be the inspirational grist Dav needs, right? But Dav rejects him: “I do not wish to know about anything that happened on this earth.” It might be hard to change the course of earthly life with that attitude. Instead of heeding Roy’s advice, Dav falls deeper into navel-gazing, imagining his future success, and generally doing anything except writing.

Dav’s dithering with the typewriter leaves Roy loose and “roving.” An amiable fellow, Roy soon takes up with two Russian oligarchs, Lev and Igor. This nefarious pair wishes to drill for oil in Snake Creek, destroying the weird paradise for profit. They plan to use charismatic, naïve Roy as their mouthpiece, a trusted liaison to the Creek community who can convince the locals on board to “drill baby drill.”

Lerman’s satire of these “ollie garx” and their relations with Roy is riddled with great gags. The oligarchs give Roy bald eagle eggs, which he proceeds to fry up to Dav’s dismay. They take him golfing and try to get him into Ayn Rand. They explain their anti-nature views—Mother Earth isn’t a caring mother but a devouring father who must, in oh-so Freudian terms, be eliminated. (Lerman, who always sneaks literary allusions into his strips, can’t resist referencing Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying during this exchange.) In one of my favorite exchanges in Escape, the oligarchs try to explain to Roy why his main talking point to convince the Snake Creek denizens to drill should be the promise of jobs:

“But people hate jobs” — yes. And it is ideology, but you’re not stupid, reader, although the oligarchs might think you are. Their attempted seduction of sweet Roy plays out against Dav’s egotistical self-seduction into a fantasy of literary greatness in the twin threads of Escape from the Great American Novel. There are meditations on art, immortality, capitalism, and the role of our native environs. There are throwaway jokes on Harold Bloom and arguments over the better English translation of Camus’ L’Etranger. There are drones and fecal preoccupations and a nice ACAB reference; there are anarchist swamp folk and bombs! And there are puns. I hope you like puns.

The strips collected in Escape from the Great American Novel span two years that often felt in “real time” like an eternity. Many of us were separated from friends and family over these months. Lerman’s gambit, intentional or otherwise, is to keep his central characters separated, which adds real tension to a comic novel that otherwise might be a loose collection of funny riffs. As I stated before, Roy and Dav are the heart of Snake Creek, so when Lerman finally reunites them the moment is not just cathartic, it’s literarily metaphysical. For all its sardonic jags, ribald japes, and erudite allusions, Escape from the Great American Novel is in the end a sweet, even heartwarming read (Dav and Roy would find a way to mock this sentiment, I’m sure). I loved it. Highly recommended.

Escape from the Great American Novel is available in print from Radiator Comics.

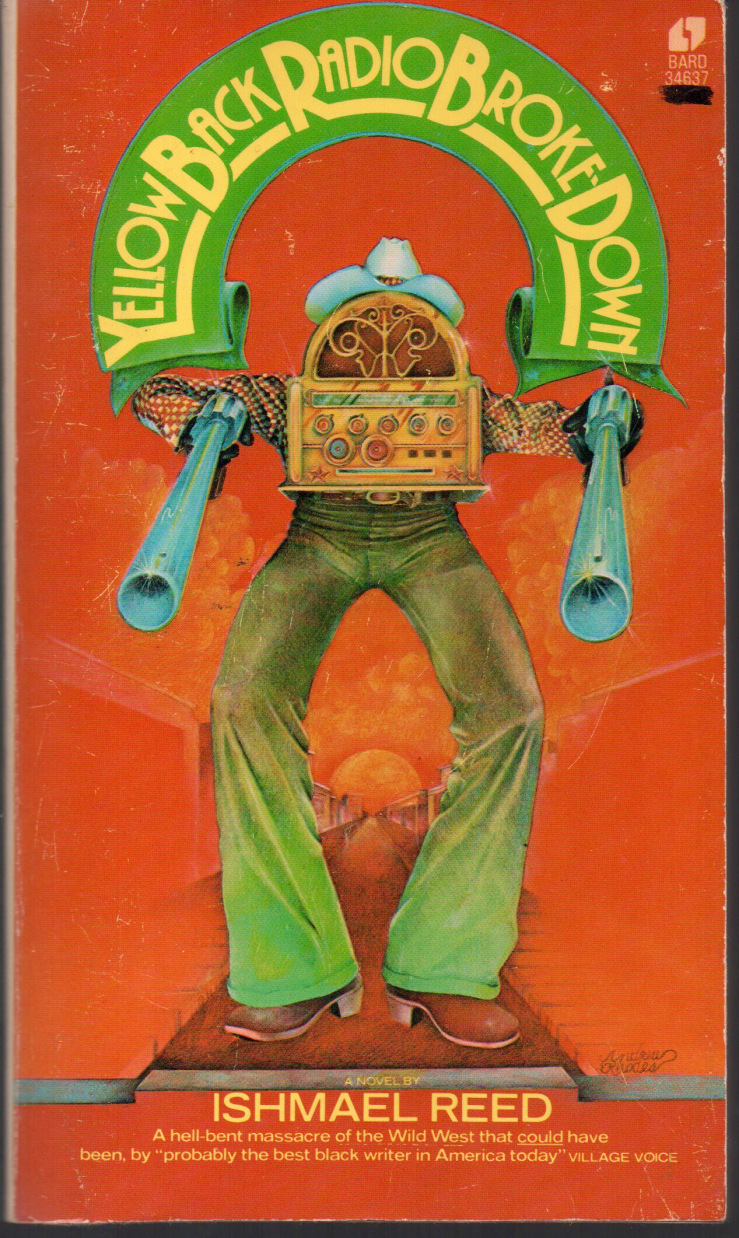

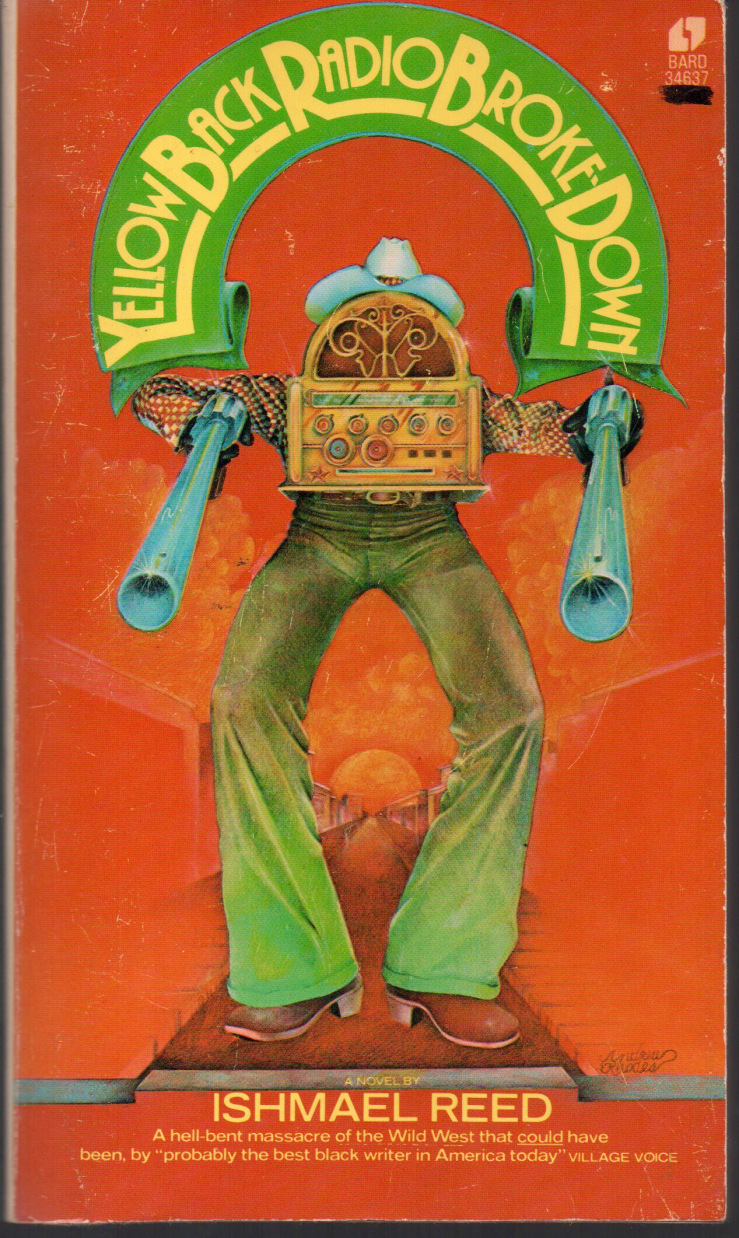

Ishmael Reed’s second novel Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down tells the story of the Loop Garoo Kid, a “desperado so onery he made the Pope cry and the most powerful of cattlemen shed his head to the Executioner’s swine.”

The novel explodes in kaleidoscopic bursts as Reed dices up three centuries of American history to riff on race, religion, sex, and power. Unstuck in time and unhampered by geographic or technological restraint, historical figures like Lewis and Clark, Thomas Jefferson, John Wesley Harding, Groucho Marx, and Pope Innocent (never mind which one) wander in and out of the narrative, supplementing its ironic allegorical heft. These minor characters are part of Reed’s Neo-HooDoo spell, ingredients in a Western revenge story that is simultaneously comic and apocalyptic in its howl against the dominant historical American narrative. Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down is a strange and marvelous novel, at once slapstick and deadly serious, exuberant in its joy and harsh in its bitterness, close to 50 years after its publication, as timely as ever.

After the breathless introduction of its hero the Loop Garoo Kid, Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down initiates its plot. Loop’s circus troupe arrives to the titular city Yellow Back Radio (the “nearest town Video Junction is about fifty miles away”), only to find that the children of the town, “dressed in the attire of the Plains Indians,” have deposed the adults:

We chased them out of town. We were tired of them ordering us around. They worked us day and night in the mines, made us herd animals harvest the crops and for three hours a day we went to school to hear teachers praise the old. Made us learn facts by rote. Lies really bent upon making us behave. We decided to create our own fiction.

The children’s revolutionary, anarchic spirit drives Reed’s own fiction, which counters all those old lies the old people use to make us behave.

Of course the old—the adults—want “their” land back. Enter that most powerful of cattlemen, Drag Gibson, who plans to wrest the land away from everyone for himself. We first meet Drag “at his usual hobby, embracing his property.” Drag’s favorite property is a green mustang,

a symbol for all his streams of fish, his herds, his fruit so large they weighed down the mountains, black gold and diamonds which lay in untapped fields, and his barnyard overflowing with robust and erotic fowl.

Drag loves to French kiss the horse, we’re told. Oh, and lest you wonder if “green” here is a metaphor for, like, new, or inexperienced, or callow: No. The horse is literally green (“turned green from old nightmares”). That’s the wonderful surreal logic of Reed’s vibrant Western, and such details (the novel is crammed with them) make Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down a joy to read.

Where was I? Oh yes, Drag Gibson.

Drag—allegorical stand-in for Manifest Destiny, white privilege, capitalist expansion, you name it—Drag, in the process of trying to clear the kids out of Yellow Back Radio, orders all of Loop’s troupe slaughtered.

The massacre sets in motion Loop’s revenge on Drag (and white supremacy in general), which unfolds in a bitter blazing series of japes, riffs, rants, and gags. (“Unfolds” is the wrong verb—too neat. The action in Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down is more like the springing of a Jack-in-the-box).

Loop goes about obtaining his revenge via his NeoHooDoo practices. He calls out curses and hexes, summoning loas in a lengthy prayer. Loop’s spell culminates in a call that goes beyond an immediate revenge on Drag and his henchmen, a call that moves toward a retribution for black culture in general:

O Black Hawk American Indian houngan of Hoo-Doo please do open up some of these prissy orthodox minds so that they will no longer call Black People’s American experience “corrupt” “perverse” and “decadent.” Please show them that Booker T and MG’s, Etta James, Johnny Ace and Bojangle tapdancing is just as beautiful as anything that happened anywhere else in the world. Teach them that anywhere people go they have experience and that all experience is art.

So much of Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down is turning all experience into art. Reed spins multivalent cultural material into something new, something arguably American. The title of the novel suggests its program: a breaking-down of yellowed paperback narratives, a breaking-down of radio signals. Significantly, that analysis, that break-down, is also synthesized in this novel into something wholly original. Rhetorically, Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down evokes flipping through paperbacks at random, making a new narrative; or scrolling up and down a radio dial, making new music from random bursts of sound; or rifling through a stack of manic Sunday funnies to make a new, somehow more vibrant collage.

Perhaps the Pope puts it best when he arrives late in the novel. (Ostensibly, the Pope shows up to put an end to Loop’s hexing and vexing of the adult citizenry—but let’s just say the two Holy Men have a deeper, older relationship). After a lengthy disquisition on the history of hoodoo and its genesis in the Voudon religion of Africa (“that strange continent which serves as the subconscious of our planet…shaped so like the human skull”), the Pope declares that “Loop Garoo seems to be practicing a syncretistic American version” of the old Ju Ju. The Pope continues:

Loop seems to be scatting arbitrarily, using forms of this and that and adding his own. He’s blowing like that celebrated musician Charles Yardbird Parker—improvising as he goes along. He’s throwing clusters of demon chords at you and you don’t know the changes, do you Mr. Drag?

The Pope here describes Reed’s style too, of course (which is to say that Reed is describing his own style, via one of his characters. The purest postmodernism). The apparent effortlessness of Reed’s improvisations—the prose’s sheer manic energy—actually camouflages a tight and precise plot. I was struck by how much of Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down’s apparent anarchy resolves into a bigger picture upon a second reading.

That simultaneous effortlessness and precision makes Reed’s novel a joy to jaunt through. Here is a writer taking what he wants from any number of literary and artistic traditions while dispensing with the forms and tropes he doesn’t want and doesn’t need. If Reed wants to riff on the historical relations between Indians and African-Americans, he’ll do that. If Reed wants to assess the relative values of Thomas Jefferson as a progressive figure, he’ll do that. If Reed wants to attack his neo-social realist critics, he’ll do that. If Reed wants to critique the relationship between militarism and science, he’ll do that. If Reed wants to tell some really dirty jokes about a threesome, he’ll do that. And you can bet if he wants some ass-kicking Amazons to show up at some point, they’re gonna show.

And it’s a great show. Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down begins with the slaughter of a circus troupe before we get to see their act. The real circus act is the novel itself, filled with orators and showmen, carnival barkers and con-artists, pistoleers and magicians. There’s a manic glee to it all, a glee tempered in anger—think of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, or Thomas Pynchon’s zany rage, or Robert Downey Sr.’s satirical film Putney Swope.

Through all its anger, Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down nevertheless repeatedly affirms the possibility of imagination and creation—both as cures and as hexes. We have here a tale of defensive and retaliatory magic. Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down is the third novel of Reed’s novels I’ve read (after Mumbo Jumbo and The Free-Lance Pallbearers), and my favorite thus far. Frankly, I needed the novel right now in a way that I didn’t know that I needed it until I read it; the contemporary novel I tried to read after it felt stale and boring. So I read Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down again. The great gift here is that Reed’s novel answers to the final line of Loop’s prayer to the Loa: “Teach them that anywhere people go they have experience and that all experience is art.” Like the children of Yellow Back Radio, Reed creates his own fiction, and invites us to do the same. Very highly recommended.

[Ed. note — Biblioklept first published this review in February of 2017.]

The Comics Journal’s lengthy write up of “The Best Comics of 2019” is up. Here’s my entry:

I’m reading Ishmael Reed’s 2011 novel Juice! right now. The narrator, a version of Reed, is a cartoonist whose comix on the O.J. Simpson case cost him his career and family. It’s not a comic, but it’s comic, and I love it.

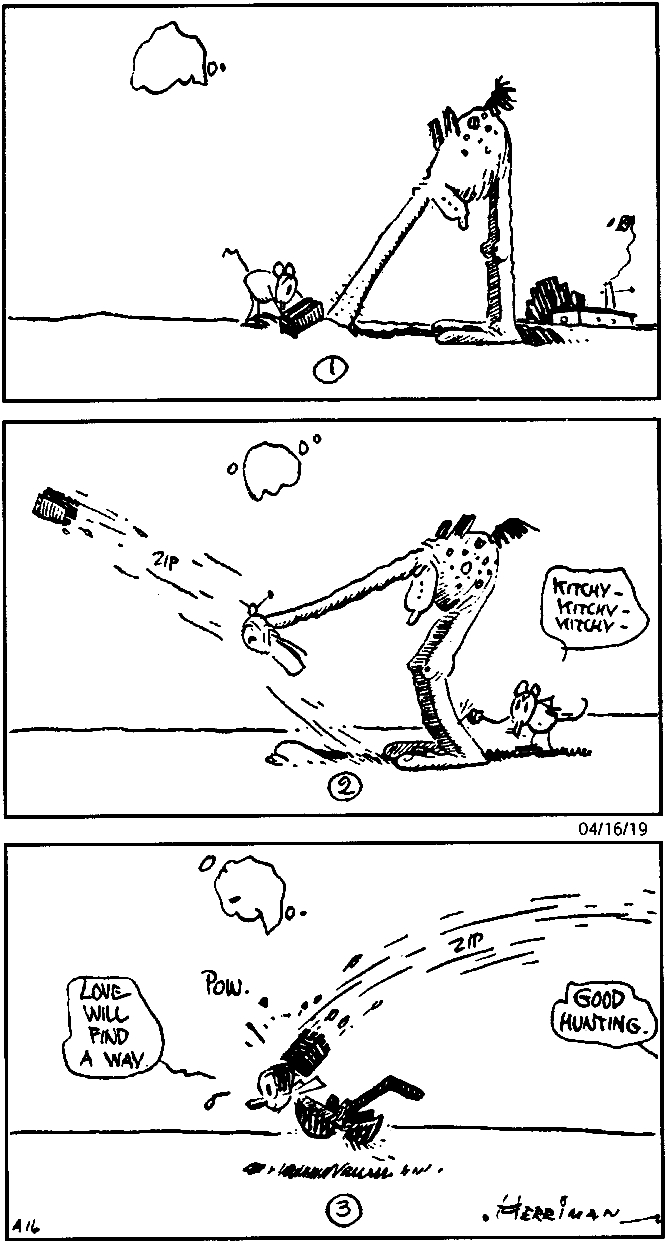

Reed and Reed’s narrator repeatedly evoke George Herriman’s Krazy Kat strips, and I’ve returned to their slapstick surreal ebullience. There’s an ecstatic nihilism to Krazy Kat (or do I mean nihilistic ecstasy?), a radical absurdity that seems to both diagnose and describe Our Big Dumb Zeitgeist of 2019 in the most perfectly oblique way. The strip’s (il)logic runs on a strange Dada engine, crashing into both sensibility and decorum. It’s a wonderful anarchist romp. I have no idea if there was some new Krazy Kat compendium that came out in 2019, but Herriman’s strip is the best critique of 2019 I can think of. (Also: Read more Ishmael Reed.)

Speaking of: Drew Lerman’s collection Snake Creek reverberates with the spirit of Krazy Kat mixed and mushed with the apocalypse ghost swamp of Walt Kelly’s Pogo, along with tinges of Garfield Goes Total Nihilist. (Who am I kidding? Garfield was always a total nihilist.) Lerman’s shaky strips approximate our own shaky days and shaky daze, evoking a Florida fit to sink into its own wild psychosphere.

Chris Ware’s novel Rusty Brown is a fucking masterpiece.

I loved Rat Time by Keiler Roberts. I missed one of my nephew’s baseball games because I started reading it one Saturday morning and then lied about having to do something work-related—like an emergency—because I wanted to finish up Rat Time instead. It made me feel Warm (& Fuzzy), despite how dry Roberts’ humor is. (Desiccant dry, folks.) Roberts’ autofiction is utterly real.

The collective of folks at The Perry Bible Fellowship continue to make good comics.

I also really admired Ben Passmore’s comic Sports Is Hell, a send-up of American massculture that simultaneously stings and enlivens its reader. The novel takes place during the aftermath of a Super Bowl featuring a Kaepernickesque (Kaepernesque?) star player. The Big Game devolves into a Big Riot, with its heroes fighting their way through the madness—think Walter Hill’s film The Warriors by way of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat. I hope Ishmael Reed will read it.

Ishmael Reed’s second novel Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down tells the story of the Loop Garoo Kid, a “desperado so onery he made the Pope cry and the most powerful of cattlemen shed his head to the Executioner’s swine.”

The novel explodes in kaleidoscopic bursts as Reed dices up three centuries of American history to riff on race, religion, sex, and power. Unstuck in time and unhampered by geographic or technological restraint, historical figures like Lewis and Clark, Thomas Jefferson, John Wesley Harding, Groucho Marx, and Pope Innocent (never mind which one) wander in and out of the narrative, supplementing its ironic allegorical heft. These minor characters are part of Reed’s Neo-HooDoo spell, ingredients in a Western revenge story that is simultaneously comic and apocalyptic in its howl against the dominant historical American narrative. Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down is a strange and marvelous novel, at once slapstick and deadly serious, exuberant in its joy and harsh in its bitterness, close to 50 years after its publication, as timely as ever.

After the breathless introduction of its hero the Loop Garoo Kid, Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down initiates its plot. Loop’s circus troupe arrives to the titular city Yellow Back Radio (the “nearest town Video Junction is about fifty miles away”), only to find that the children of the town, “dressed in the attire of the Plains Indians,” have deposed the adults:

We chased them out of town. We were tired of them ordering us around. They worked us day and night in the mines, made us herd animals harvest the crops and for three hours a day we went to school to hear teachers praise the old. Made us learn facts by rote. Lies really bent upon making us behave. We decided to create our own fiction.

The children’s revolutionary, anarchic spirit drives Reed’s own fiction, which counters all those old lies the old people use to make us behave.

Of course the old—the adults—want “their” land back. Enter that most powerful of cattlemen, Drag Gibson, who plans to wrest the land away from everyone for himself. We first meet Drag “at his usual hobby, embracing his property.” Drag’s favorite property is a green mustang,

a symbol for all his streams of fish, his herds, his fruit so large they weighed down the mountains, black gold and diamonds which lay in untapped fields, and his barnyard overflowing with robust and erotic fowl.

Drag loves to French kiss the horse, we’re told. Oh, and lest you wonder if “green” here is a metaphor for, like, new, or inexperienced, or callow: No. The horse is literally green (“turned green from old nightmares”). That’s the wonderful surreal logic of Reed’s vibrant Western, and such details (the novel is crammed with them) make Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down a joy to read.

Where was I? Oh yes, Drag Gibson.

Drag—allegorical stand-in for Manifest Destiny, white privilege, capitalist expansion, you name it—Drag, in the process of trying to clear the kids out of Yellow Back Radio, orders all of Loop’s troupe slaughtered.

The massacre sets in motion Loop’s revenge on Drag (and white supremacy in general), which unfolds in a bitter blazing series of japes, riffs, rants, and gags. (“Unfolds” is the wrong verb—too neat. The action in Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down is more like the springing of a Jack-in-the-box).

Loop goes about obtaining his revenge via his NeoHooDoo practices. He calls out curses and hexes, summoning loas in a lengthy prayer. Loop’s spell culminates in a call that goes beyond an immediate revenge on Drag and his henchmen, a call that moves toward a retribution for black culture in general:

O Black Hawk American Indian houngan of Hoo-Doo please do open up some of these prissy orthodox minds so that they will no longer call Black People’s American experience “corrupt” “perverse” and “decadent.” Please show them that Booker T and MG’s, Etta James, Johnny Ace and Bojangle tapdancing is just as beautiful as anything that happened anywhere else in the world. Teach them that anywhere people go they have experience and that all experience is art.

So much of Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down is turning all experience into art. Reed spins multivalent cultural material into something new, something arguably American. The title of the novel suggests its program: a breaking-down of yellowed paperback narratives, a breaking-down of radio signals. Significantly, that analysis, that break-down, is also synthesized in this novel into something wholly original. Rhetorically, Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down evokes flipping through paperbacks at random, making a new narrative; or scrolling up and down a radio dial, making new music from random bursts of sound; or rifling through a stack of manic Sunday funnies to make a new, somehow more vibrant collage.

Perhaps the Pope puts it best when he arrives late in the novel. (Ostensibly, the Pope shows up to put an end to Loop’s hexing and vexing of the adult citizenry—but let’s just say the two Holy Men have a deeper, older relationship). After a lengthy disquisition on the history of hoodoo and its genesis in the Voudon religion of Africa (“that strange continent which serves as the subconscious of our planet…shaped so like the human skull”), the Pope declares that “Loop Garoo seems to be practicing a syncretistic American version” of the old Ju Ju. The Pope continues:

Loop seems to be scatting arbitrarily, using forms of this and that and adding his own. He’s blowing like that celebrated musician Charles Yardbird Parker—improvising as he goes along. He’s throwing clusters of demon chords at you and you don’t know the changes, do you Mr. Drag?

The Pope here describes Reed’s style too, of course (which is to say that Reed is describing his own style, via one of his characters. The purest postmodernism). The apparent effortlessness of Reed’s improvisations—the prose’s sheer manic energy—actually camouflages a tight and precise plot. I was struck by how much of Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down’s apparent anarchy resolves into a bigger picture upon a second reading.

That simultaneous effortlessness and precision makes Reed’s novel a joy to jaunt through. Here is a writer taking what he wants from any number of literary and artistic traditions while dispensing with the forms and tropes he doesn’t want and doesn’t need. If Reed wants to riff on the historical relations between Indians and African-Americans, he’ll do that. If Reed wants to assess the relative values of Thomas Jefferson as a progressive figure, he’ll do that. If Reed wants to attack his neo-social realist critics, he’ll do that. If Reed wants to critique the relationship between militarism and science, he’ll do that. If Reed wants to tell some really dirty jokes about a threesome, he’ll do that. And you can bet if he wants some ass-kicking Amazons to show up at some point, they’re gonna show.

And it’s a great show. Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down begins with the slaughter of a circus troupe before we get to see their act. The real circus act is the novel itself, filled with orators and showmen, carnival barkers and con-artists, pistoleers and magicians. There’s a manic glee to it all, a glee tempered in anger—think of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, or Thomas Pynchon’s zany rage, or Robert Downey Sr.’s satirical film Putney Swope.

Through all its anger, Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down nevertheless repeatedly affirms the possibility of imagination and creation—both as cures and as hexes. We have here a tale of defensive and retaliatory magic. Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down is the third novel of Reed’s novels I’ve read (after Mumbo Jumbo and The Free-Lance Pallbearers), and my favorite thus far. Frankly, I needed the novel right now in a way that I didn’t know that I needed it until I read it; the contemporary novel I tried to read after it felt stale and boring. So I read Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down again. The great gift here is that Reed’s novel answers to the final line of Loop’s prayer to the Loa: “Teach them that anywhere people go they have experience and that all experience is art.” Like the children of Yellow Back Radio, Reed creates his own fiction, and invites us to do the same. Very highly recommended.

[Ed. note—Biblioklept originally ran this review in February of 2017.]