“October”

by

May Swenson

1

A smudge for the horizon

that, on a clear day, shows

the hard edge of hills and

buildings on the other coast.

Anchored boats all head one way:

north, where the wind comes from.

You can see the storm inflating

out of the west. A dark hole

in gray cloud twirls, widens,

while white rips multiply

on the water far out.

Wet tousled yellow leaves,

thick on the slate terrace.

The jay’s hoarse cry. He’s

stumbling in the air,

too soaked to fly.

2

Knuckles of the rain

on the roof,

chuckles into the drain-

pipe, spatters on

the leaves that litter

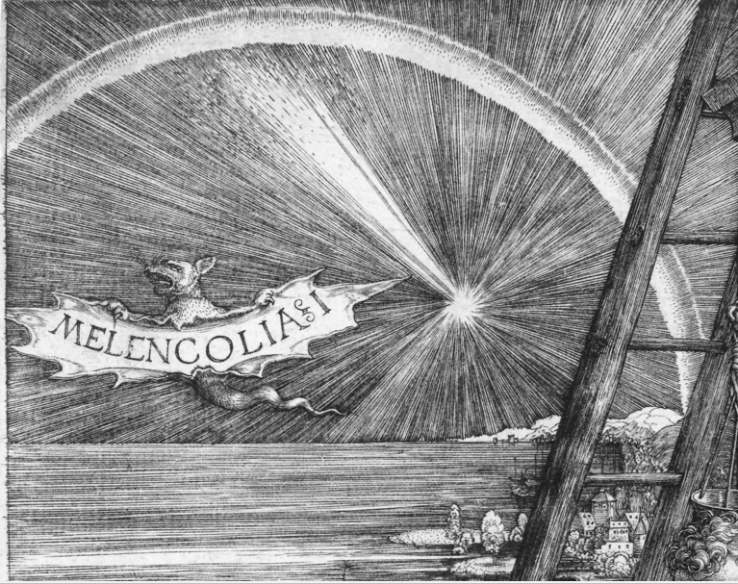

the grass. Melancholy

morning, the tide full

in the bay, an overflowing

bowl. At least, no wind,

no roughness in the sky,

its gray face bedraggled

by its tears.

3

Peeling a pear, I remember

my daddy’s hand. His thumb

(the one that got nipped by the saw,

lacked a nail) fit into

the cored hollow of the slippery

half his knife skinned so neatly.

Dad would pare the fruit from our

orchard in the fall, while Mother

boiled the jars, prepared for

“putting up.” Dad used to darn

our socks when we were small,

and cut our hair and toenails.

Sunday mornings, in pajamas, we’d

take turns in his lap. He’d help

bathe us sometimes. Dad could do

anything. He built our dining table,

chairs, the buffet, the bay window

seat, my little desk of cherry wood

where I wrote my first poems. That

day at the shop, splitting panel

boards on the electric saw (oh, I

can hear the screech of it now,

the whirling blade that sliced

my daddy’s thumb), he received the mar

that, long after, in his coffin,

distinguished his skilled hand.

4

I sit with braided fingers

and closed eyes

in a span of late sunlight.

The spokes are closing.

It is fall: warm milk of light,

though from an aging breast.

I do not mean to pray.

The posture for thanks or

supplication is the same

as for weariness or relief.

But I am glad for the luck

of light. Surely it is godly,

that it makes all things

begin, and appear, and become

actual to each other.

Light that’s sucked into

the eye, warming the brain

with wires of color.

Light that hatched life

out of the cold egg of earth.

5

Dark wild honey, the lion’s

eye color, you brought home

from a country store.

Tastes of the work of shaggy

bees on strong weeds,

their midsummer bloom.

My brain’s electric circuit

glows, like the lion’s iris

that, concentrated, vibrates

while seeming not to move.

Thick transparent amber

you brought home,

the sweet that burns.

6

“The very hairs of your head

are numbered,” said the words

in my head, as the haircutter

snipped and cut, my round head

a newel poked out of the tent

top’s slippery sheet, while my

hairs’ straight rays rained

down, making pattern on the neat

vacant cosmos of my lap. And

maybe it was those tiny flies,

phantoms of my aging eyes, seen

out of the sides floating (that,

when you turn to find them

full face, always dissolve) but

I saw, I think, minuscule,

marked in clearest ink, Hairs

#9001 and #9002 fall, the cut-off

ends streaking little comets,

till they tumbled to confuse

with all the others in their

fizzled heaps, in canyons of my

lap. And what keeps asking

in my head now that, brushed off

and finished, I’m walking

in the street, is how can those

numbers remain all the way through,

and all along the length of every

hair, and even before each one

is grown, apparently, through

my scalp? For, if the hairs of my

head are numbered, it means

no more and no less of them

have ever, or will ever be.

In my head, now cool and light,

thoughts, phantom white flies,

take a fling: This discovery

can apply to everything.

7

Now and then, a red leaf riding

the slow flow of gray water.

From the bridge, see far into

the woods, now that limbs are bare,

ground thick-littered. See,

along the scarcely gliding stream,

the blanched, diminished, ragged

swamp and woods the sun still

spills into. Stand still, stare

hard into bramble and tangle,

past leaning broken trunks,

sprawled roots exposed. Will

something move?—some vision

come to outline? Yes, there—

deep in—a dark bird hangs

in the thicket, stretches a wing.

Reversing his perch, he says one

“Chuck.” His shoulder-patch

that should be red looks gray.

This old redwing has decided to

stay, this year, not join the

strenuous migration. Better here,

in the familiar, to fade.