Tag: rain

Under the Unminding Sky — Gregory Thielker

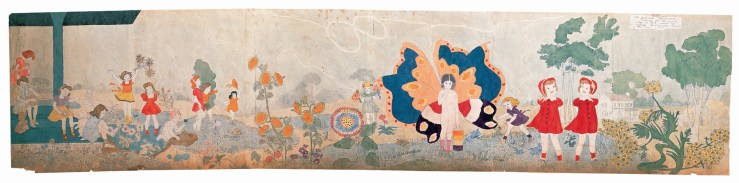

176 part two. Jennie Richee waiting for the rain to stop… — Henry Darger

Drops of Rain, 1903 — Clarence White

“Rain” — Roberto Bolaño

Heavy Rain — Utagawa Kuniyoshi

“Rain” — Alice Meynell

“Rain”

by

Alice Meynell

Not excepting the falling stars—for they are far less sudden—there is nothing in nature that so outstrips our unready eyes as the familiar rain. The rods that thinly stripe our landscape, long shafts from the clouds, if we had but agility to make the arrowy downward journey with them by the glancing of our eyes, would be infinitely separate, units, an innumerable flight of single things, and the simple movement of intricate points.

The long stroke of the raindrop, which is the drop and its path at once, being our impression of a shower, shows us how certainly our impression is the effect of the lagging, and not of the haste, of our senses. What we are apt to call our quick impression is rather our sensibly tardy, unprepared, surprised, outrun, lightly bewildered sense of things that flash and fall, wink, and are overpast and renewed, while the gentle eyes of man hesitate and mingle the beginning with the close. These inexpert eyes, delicately baffled, detain for an instant the image that puzzles them, and so dally with the bright progress of a meteor, and part slowly from the slender course of the already fallen raindrop, whose moments are not theirs. There seems to be such a difference of instants as invests all swift movement with mystery in man’s eyes, and causes the past, a moment old, to be written, vanishing, upon the skies.

The visible world is etched and engraved with the signs and records of our halting apprehension; and the pause between the distant woodman’s stroke with the axe and its sound upon our ears is repeated in the impressions of our clinging sight. The round wheel dazzles it, and the stroke of the bird’s wing shakes it off like a captivity evaded. Everywhere the natural haste is impatient of these timid senses; and their perception, outrun by the shower, shaken by the light, denied by the shadow, eluded by the distance, makes the lingering picture that is all our art. One of the most constant causes of all the mystery and beauty of that art is surely not that we see by flashes, but that nature flashes on our meditative eyes. There is no need for the impressionist to make haste, nor would haste avail him, for mobile nature doubles upon him, and plays with his delays the exquisite game of visibility.

Momently visible in a shower, invisible within the earth, the ministration of water is so manifest in the coming rain-cloud that the husbandman is allowed to see the rain of his own land, yet unclaimed in the arms of the rainy wind. It is an eager lien that he binds the shower withal, and the grasp of his anxiety is on the coming cloud. His sense of property takes aim and reckons distance and speed, and even as he shoots a little ahead of the equally uncertain ground-game, he knows approximately how to hit the cloud of his possession. So much is the rain bound to the earth that, unable to compel it, man has yet found a way, by lying in wait, to put his price upon it. The exhaustible cloud “outweeps its rain,” and only the inexhaustible sun seems to repeat and to enforce his cumulative fires upon every span of ground, innumerable. The rain is wasted upon the sea, but only by a fantasy can the sun’s waste be made a reproach to the ocean, the desert, or the sealed-up street. Rossetti’s “vain virtues” are the virtues of the rain, falling unfruitfully.

Baby of the cloud, rain is carried long enough within that troubled breast to make all the multitude of days unlike each other. Rain, as the end of the cloud, divides light and withholds it; in its flight warning away the sun, and in its final fall dismissing shadow. It is a threat and a reconciliation; it removes mountains compared with which the Alps are hillocks, and makes a childlike peace between opposed heights and battlements of heaven.

Shower — Kitagawa Utamaro

Scheveningen Women and Other People Under Umbrellas — Vincent van Gogh

Unloved (Peanuts)