Amy Hempel talks about studying under Gordon Lish (and how Steve Martin influenced her) in her 2003 interview with The Paris Review—

INTERVIEWER

Why Lish?

HEMPEL

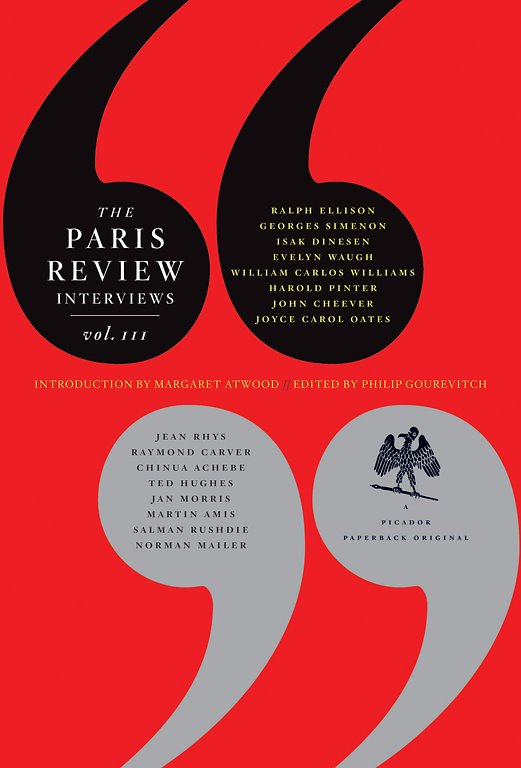

At Esquire in the seventies and, later, at Knopf, he was publishing the voices that interested me most. I felt allied with his choices, so he was the one I wanted to work with. Writers like Raymond Carver, Barry Hannah, Mary Robison. These were the three who had the most effect on me when I started.

INTERVIEWER

What about their work interested you?

HEMPEL

They didn’t sound like anyone else I had read. For me, they redefined what a story could be—the thing happening off to the side of the story other writers were telling; they would start where someone else would leave off, or stop where someone else would start. As Hannah said later in Boomerang, a lot of people have their overview, whereas he has his “underview,” scouting “under the bleachers, for what life has dropped.”

INTERVIEWER

Do you remember the first class?

HEMPEL

Vividly. The assignment was to write our worst secret, the thing we would never live down, the thing that, as Gordon put it, “dismantles your own sense of yourself.” And everybody knew instantly what that thing, for them, was. We found out immediately that the stakes were very high, that we were expected to say something no one else had said, and to divulge much harder truths than we had ever told or ever thought to tell. No half-measures. He thought any of us could do it if we wanted it badly enough. And that, when I was starting out, was a great thing to hear from someone who would know.

INTERVIEWER

What was, if you can say, your “worst secret”?

HEMPEL

I failed my best friend when she was dying. It became the subject of the first story I wrote, “In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson Is Buried.”

INTERVIEWER

You stayed on in his workshop as a student for years. You must have been repeatedly humbled.

HEMPEL

I felt humbled by realizing how hard the job was. How hard it is to write a moving, worthwhile, memorable story. But more often I was inspired. It turned out that one of the most helpful things I did without knowing it would be helpful later was hang out with stand-up comics in San Francisco. I went to their shows night after night after night. I watched them performing, working through the same material. I saw some nights it killed and other nights it bombed. All that time I was observing nuance, inflection, timing, how the slightest difference mattered. How the littlest leaning on a word—or leaning away from it—would get the laugh, and this lesson was so valuable. And the improv work—they called it “being human on purpose,” this falling back on the language in your mouth—was hugely important. Just listening to what you’re saying. I learned this when my late friend Morgan Upton, an actor and member of the Committee, took me to a Steve Martin show at the Boarding House in San Francisco. Back in the green room, Steve Martin was sick, but preparing to do his show anyway. I told him I admired that, I said I couldn’t go out there and make people laugh if I were sick. And he said, Don’t be silly—you couldn’t do it if you were well. A brilliant reply on any number of levels. I based an early story, “Three Popes Walk into a Bar,” on that night. Then I ran into him about twenty years later and reminded him of our exchange. He laughed and said, “It sounds mean!” But I thought it was great.

Listening to Gordon Lish read selections from

Listening to Gordon Lish read selections from